How do you think about storytelling when it comes to Ear Hustle? How does an episode take shape?

Nigel: We start with a story idea. At the beginning of a season, the whole team sits down and we just throw a bunch of story ideas out there. We always want to make sure that we’re telling stories that haven’t been heard, but also that we can try to tell in new ways, so we stay creative. Then we start doing interviews. We’ll have a handful of questions, but we really like to be a little more improvisational, to leave it open for different directions. Then we shape the stories. It’s a very collaborative team. We’re the co-hosts and the co-creators, but we have an editor, Amy Standen, our executive producer, Bruce Wallace, Rahsaan “New York” Thomas, who was inside San Quentin, who’s now out, and we work closely, pulling tape, writing out scripts. We do a ton of editing…

Earlonne: A ton of editing.

Nigel: We had no idea how much writing was going to be involved because when we started back in 2016, we’re like, Oh, you just talk. But we do a lot of writing. Earlonne does the sound design and that’s also a huge editing process. I think we both learned to have thicker skins about editing. But we are tinkering away on stories…

Earlonne: Until a couple of hours before they need to go out.

Nigel: Which is sometimes two in the morning.

Earlonne, can you describe what sound design means?

Earlonne: I would say it’s a rhythm and a beat that helps escort the story. It accentuates the story, helps people digest it a little better. People can go, Okay, I got something to ride to.

With so many people involved, I’m curious about the collaboration, between the two of you, but also with the team, and then the people you’re interviewing. What are those challenges, and what are some of the benefits?

Nigel: I worked as a visual artist for about 30 years before I started this project—I was used to working alone, making all of the decisions, and being solely responsible for things that succeeded and failed. I will admit, it took me a while to let go of the reins a little bit and let other people’s expertise and creativity be part of it. Because for me, the creative part is so important. What I came to realize by holding the reins too tight, I was squashing that with other team members, not letting them have their creative part and not trusting that they were as excited and as intent about it as I was. Well, not with Earlonne. I can’t explain why, but for whatever reason, we clicked so clearly, and understood what each other could and couldn’t do.

Earlonne: For me, the good thing is when we can get a lot of different voices in one episode. Because for one, you have more people that’s in the institution that’s involved. Two, it’s always good when we got one story with different threads meeting a similar end. Adding all the voices in, that’s always a good thing.

Nigel: Collaborations work when you find the right people to collaborate with. That might sound trite, but it is so true. I think there’s something ineffable when you find the right person or people and then you just hold on because, boy, the dynamic can shift really easily with just one wrong collaborator. We’re really fortunate that we have a very strong team.

Can you tell me about your team on the inside?

Nigel: This has been interesting because Earlonne and I met in 2012 and we came up with the idea of the podcast on October 5th, 2015. I know that because we have notes we wrote about our plan. When Earlonne got out, that really changed the inside dynamic because now we bring on new people, and when you bring somebody onto a project that’s already moving forward, the relationship is different. We taught each other how to do stuff, and we were equal partners. Now it’s a little bit more of an educational thing. We have a great team inside, four relatively new producers who do segments of stories or interviews. And we’re going to be starting a workshop inside, teaching these guys more of the ins and outs.

Earlonne: The advantage of that is to give more people the opportunity to not only get involved but to learn a new skill set. The more the merrier for us. Right now we’re currently setting up a studio in the women’s facility, the California Institution for Women (CIW) alongside Uncuffed, another podcast started inside of San Quentin and Solano. And we’re making regular trips to the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF). It is my guess that the women’s team is going to give the men’s team a run for their money. We have to get into the women’s prisons because the men have all kinds of programs. The women don’t. You have 35 men’s prisons and only two women’s prisons. They don’t get anywhere near the volunteers, the programs, the media centers, all that. So we’re trying to show the love.

When you came up with the idea for Ear Hustle in 2015, what was your intent, and has that mission evolved over the years?

Earlonne: It’s crazy when you say, What was the intent? The intent was to air it inside of San Quentin. The bigger goal was to air it inside all of the prisons. It wasn’t even the outside world.

Nigel: Yeah, that was the dream, to do a storytelling project that wasn’t like the news, wasn’t journalism. It was from the perspective of artists just telling the everyday stories of life inside for the people inside prison to hear. San Quentin has a closed-circuit station, so we thought, Easy, okay, we’ll be able to get this on the closed-circuit station. If we can get it in all the prisons in California, that would be incredible.

If we looked at that sheet that we wrote on October 5th, 2015, we had: We are going to be the hosts and escorts. We want to look at the details of life. We’re going to stay away from crime and statistics and intentionally trying to change people’s minds about prisons. We just want to tell everyday stories. And that has not really changed. We’ve gotten better at it, but we weren’t trying to do it for anyone else except people in prison.

Earlonne: And we had to curse. I have not been to a penitentiary where they don’t curse.

Nigel: Then we ended up winning a contest from Radiotopia. That meant that we were aired outside of the prison for much longer before we were aired inside the prison. Which is funny—it seemed like it would’ve been impossible to get this outside of the prison, but it just happened that way.

When you knew that it would be people outside who were listening, did that change the way you thought about telling these stories?

Earlonne: No. To me, it was still for the people that were inside. And then it was more of the general public that was ear hustling—they was hustling what we was doing for the people inside. Kind of like they was listening to something that they shouldn’t have been listening to. And it was good for ‘em, and they was liking it.

Nigel: But it’s weird to think about. The idea did not change, and the stories have not changed substantially. They’ve gotten better and more complex, but the through line and the intent have been solid for the 13 seasons that we’ve been operating.

Earlonne: Usually when the media used to come inside the prison, they will do an interview, but then when they get outside the prison, the narrative switches—the whole intent, everything changes. Now you have tape where you might be saying something that you weren’t really saying. So our whole mission was like, Nah, we’re going to let individuals tell their own stories. It goes back to the escort. Nigel was the outside voice, and I was the inside voice.

Nigel: We were very clear from the start: This is an inside and an outside collaboration, and it’s always going to be that way. And the other thing that we were very clear about, which doesn’t sound radical, but it actually was, was that our stories were going to have humor, laughter, surprise, delight—things that people who haven’t been in prison maybe don’t associate with prison. I didn’t until I started going in. And I think that makes our stories all the better, that in any episode you’re going to laugh and you’re going to be like, Oh my God, I can’t believe it. And you’re going to also hear things that are gutting and will keep you up at night. That’s very intentional. We want all the emotions to be mixed around and challenge people’s assumptions.

Earlonne, were you a creative kid? Did you love telling stories when you were younger?

Earlonne: I was definitely a creative kid. I was a fix-it kid. I used to fix everything. I always liked storytelling. I was into movies, wanting to make movies. But I started going to prison when I was 17. I spent a total of 27 years in prison. So a lot of my creativity went there.

Nigel: People in prison are so creative because you’ve got to solve so many problems. We always talk about…

Earlonne: …prison ingenuity, yeah. People in prison make up all kinds of stuff. When I was in another state prison, I seen that San Quentin had a film school. I was like, I need to get there. Because San Quentin is…I don’t want to say the bougiest prison they got in the system, but it was like the must-go-to prison. It’s hard to get there. So I had to be creative. I was in a level three facility. I knew that San Quentin and Soledad were the only prisons they can send me to as a level two. I also knew the prison I was in didn’t have a mental health program, so I had to do my due diligence, and watch about 10 to 12 Zoloft commercials, follow the ball. And then I went to the psych and was like, “I’m depressed, and this is why.” And by saying that, they got to send me somewhere with a mental health program that’s within my custody level. I ended up going to another prison that really depressed me; I was really going through what the ball [from the Zoloft commercial] was saying. And then they had a volunteer list to go to San Quentin. I was able to get there within 67 days of my transfer. And that’s where Nigel and I met.

Nigel, how did your childhood influence the way you think about creativity today?

Nigel: I’ve always been somebody who collects things and looks at stuff often overlooked. One of my first memories of doing something like that was in second grade. I had shoe boxes lined up in my closet with labels on them for different things—found stones, bottle caps, leaves. I always loved to eavesdrop on people, and I had notebooks of overheard conversations. I was always curious about why people do things.

Earlonne: She ain’t stopped none of that yet.

Nigel: It hasn’t changed. Forever I’ve worked with small, overlooked things and stories. Doing the podcast was just an extension of that. I’m a pretty shy person, and I used photography for a long time as a way to access other people. It’s the same with the podcast. When you have a microphone and a story you want to tell, you can just get in there and ask all of your questions. Our personalities work really well in interviews. We have different styles and we get different sides of people through the way we interact.

Earlonne: Us coming from the audio world without cameras, without people tripping off what they look like, you talk to ‘em and they just get immersed in what the truth is or what their truth is or what their experience is. They’re ready to just tell it all.

Nigel: Most people, not just people in prison, don’t get the attention or the curiosity directed at them that they should. So when you show genuine interest in somebody, you kind of both exhale together and people are willing to go deep. And I love that it’s always a delight, even when the conversations are difficult. It’s a very life-affirming thing to have these conversations with people. When Earlonne and I started this, neither of us had really done audio, we didn’t know the rules. And I think that really helped us. I mean, we’ve learned them along the way, but we just knew what we wanted to do and so we went about it in our own way. And for us that worked fine to not know, to find out together.

If the mission of Ear Hustle is simply telling people’s stories, how do you measure success?

Nigel: I measure the success by the experience that stays with me from doing the story and the connection that I feel with that person. When the experience has challenged me, and I see the world in a different way, or I start thinking about something I never thought about, to me that’s a really successful story because I intuit that the person we spoke to is having that experience. And then I hope that the listeners are having that experience. It’s a gentle thing that happens, but it’s powerful.

Earlonne: Mine is more shallow then. I know it’s successful when we bring out Kleenex.

Is there one episode you find particularly memorable, either in the making of it or in the way that it was received once you put it out into the world?

Earlonne: Oh, man. Early on we did “Misguided Loyalty.” It was about a gang member and he wanted to be the hardest dude in this gang. So he shot and killed a rival gang member. Unbeknownst to him, that gang retaliated and killed his younger brother and his mother. When we did his story, it was more about wanting other young individuals thinking about getting in gangs to hear this, to take a moment and pause. That was one of the deep ones.

Nigel: I have so many. But there’s one from early on called “Looking Out,” about this guy called Rauch who really does not get along with people, and he loves critters, and he responds to them in prison. I loved it because it really showed the three components of Ear Hustle. You go from laughing, to being astounded, to just being gutted. And I think it did that really beautifully. But recently, we did a story about hospice called, “What’s Up, Michael Freeman?” And it was such a hard story to do, but we had really amazing conversations in there. I am really proud of what we did as a team. I think it’s a really good story about an important subject that people don’t want to think about—dying in general but also dying in prison.

Earlonne: And I think pretty much everybody in the story died before the story came out.

Nigel: But believe it or not, there’s a lot of laughs in it, too. A lot of beautiful moments.

Earlonne, can you talk about the advocacy you’ve been doing around California’s three-strikes law?

Earlonne: When you get the three-strikes law, you end up in prisons where you start seeing just how many people are in there because of that law. And most of the people that had the three-strike law were African Americans. But nobody was trying to change it. Nobody was trying to reverse any convictions. The legislature was not getting involved.

So I was like, let me just go read the books. And that’s where I started coming with my advocacy work. I started reading the laws, reading how you put an initiative on the ballot. And I went that route. And that’s a stressful-ass route, trying to have a full-time job and be a full-time advocate—you burn out. One of my missions when I got out of prison was abolishing the law, but I realized it is not a popular idea. I think it’s because so many laws are entwined in that one law over the last 30 years that if we kill that law, every sentence in California would probably have to be changed.

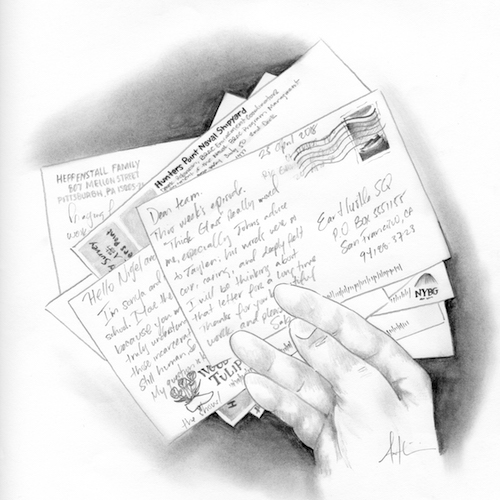

Nigel: One thing I notice with Earlonne is that I’ve never been with anybody who gets more fucking phone calls. He is constantly on the phone with people from prison who are asking him for help. He’s giving people advice, helping them connect with others who can help them, tirelessly. And to me, that is an important kind of advocacy. It’s different than trying to change the law, it’s really about changing individuals’ lives.

Earlonne: Everyone in the California Department of Corrections has my number. A lot of them haven’t been heard, people haven’t paid attention. And I think what we do brings empathy to the system, to the movement, to people. Listening to these stories, people see the other side of it. After a while, I understood my role in all this: to inspire everybody that’s in there.

It sounds like Ear Hustle really instigates a lot of change with people on the inside and the outside.

Earlonne: Early on when we had correction commissioners from other states coming in and they used to be like, “Man, I’ve been working here for 25 years and never had the insight I have now. Just from your episodes.”

Nigel: Yeah. I think there’s a lot of stuff that Ear Hustle does that people don’t quite realize in terms of changing people’s minds. We don’t always talk about it, but hearing from people who work in other prisons…

Earlonne: Judges, prosecutors, teachers, professors…

Nigel: …it’s great. From two people who didn’t know what the hell they were doing.

There’s a powerful episode in season eight called “Camp Grace,” about a program that brought kids into Salinas Valley State Prison to spend two days reconnecting with their dads, who they hadn’t seen in years. And you asked interviewees to highlight “a rose,” something positive about the experience, and “a thorn,” something challenging. I ask my 6-year-old the same questions, usually at the end of the day, and I also ask him for “a bud,” something that’s about to blossom. Reflecting on Ear Hustle, or life in general, what’s your current rose, thorn, and bud?

Nigel: My grandson is the biggest rose in my life. It’s such a surprise to know that kind of love. That’s my personal rose. My Ear Hustle rose is our team and how we support each other and how that allows us to do really hard work. Going into the women’s prison, that’s another rose. So I have a bouquet.

Earlonne: It’s a trip because I have, like she said, a bouquet of roses. My rose with Ear Hustle is, I am free today because of it. My first parole board hearing was 2028, and I was let out in 2018. Another one of my roses: I was able to get out of prison and see my parents before one of ’em passed.

I would say a thorn is when people don’t get it. People may feel that we don’t understand. People may look at it and think that we may not have prison experience maybe, I don’t know.

Oh, and my bud. A lot of people listen to Ear Hustle, but I want more of the African-American community to tune in. We’re just going to continue to push for that. A lot of our stories cover people in that community, people of color, and I think our episodes can be instrumental in some ways in their life. What’s your bud Nigel?

Nigel: I think we share this bud: What we’re trying to start at the women’s prison, it’s really going to be happening in the next four months or so. I’m trying to think of a thorn… Maybe this is part of spending time in prison, but I really live by gratitude now in a way I never did before. I don’t want to say I have gratitude because I see things that are upsetting in prison, it’s not that. Being able to do this work and realizing the power that two people have, that on paper did not look like they had a lot of power. The friendship that we have and the work that we do together and with the team—there are so many blessings from doing Ear Hustle. I really only see roses.