- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker August 14, 2012

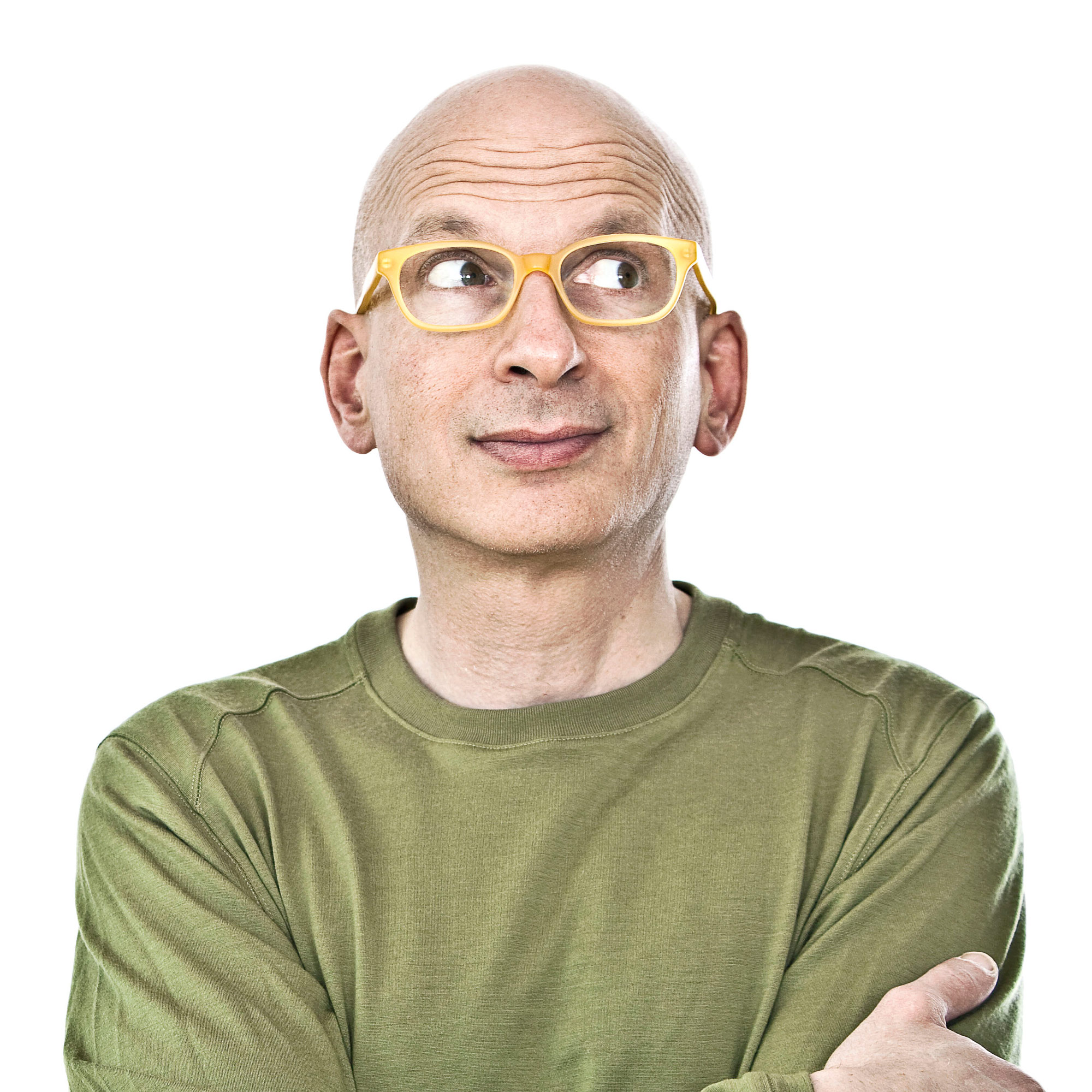

- Photo by Brian Bloom

Seth Godin

- entrepreneur

- writer

Seth Godin is an entrepreneur, author, and public speaker who pioneered the idea of permission marketing. He has written 14 bestselling books and his blog is perhaps the most popular in the world written by a single individual. His first internet company, Yoyodyne, was acquired by Yahoo! in 1998 and he served as VP of Direct Marketing at Yahoo! for a year. His company, Squidoo.com, is ranked among the top 75 sites in the US.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming an entrepreneur, author, and speaker.

When I was 14, two things happened. One, I started my first little business and two, I started reading my father’s copies of Forbes magazine. What I discovered is that some people were able to make a living basically doing what I do now. There are plenty of people who back into what it is they want to do, but even though I took many side roads along the way, this is exactly what I wanted to do 40 years ago. I’m thrilled that the universe lined up to let someone as easily distracted and ADD as me figure out a way to earn a fine living making a ruckus and helping people get to where they want to go.

I said there were many distractions along the way. I ran a bunch of businesses in high school that helped me get into college and in college, I co-founded a company nonprofit that was part of Tufts, where I attended. We ended up with 400 temporary employees who were all college students. We had a snack bar, a ticket bureau, a travel agency, a concert promotion business, a birthday cake delivery business, a bagel business—we invented new businesses every ten days or so. It was a great laboratory because I had nothing to lose. I didn’t own any of the profit of the company and we did it for all the right reasons. It was fun and useful and entertaining.

That experience got me, completely without credentials, into Stanford Business School as the second youngest person in my class. Everybody else there had to work two years at an investment or commercial bank and they hated the fact that they had wasted two years of their life. Plenty of people thought I didn’t have a chance because I hadn’t done that and they were right. I wasn’t particularly good at business school; I was good at answering the conceptual questions, but really bad at building spreadsheets and stuff.

From there, I ended up at a software company where I was the thirtieth employee. They were well-funded and the president was a great guy; he was my mentor and let me make all sorts of mistakes, many of which were very amusing. Then during one week in 1986, I got married, quit my job, moved to New York City, and started my own company. I would not suggest to anyone to do all four of those things at the same time.

In the years that followed, I just failed and failed and failed and failed. I got 900 rejection letters in the mail from book publishers. I would go window shopping at restaurants and go home and eat macaroni and cheese. It was a very long slog, right on the edge of bankruptcy for almost eight years. I did a whole bunch of books as a book packager; I did almanacs; I did books on personal finance; I did the Professor Barndt’s On-the-Spot Spot and Stain Removal Guide; I did a book which I’m embarrassed about called Email Addresses of the Rich and Famous. (laughing)

In 1991, I started a company that did online computer games that were run on email and sponsored by Fortune 500 companies. I worked with AOL, eWorld, CompuServe, and some online services that never really saw the light of day. That was what I was busy doing when the Internet came to be and we turned that company into the biggest online direct marketing company there was. We started the idea of Permission Marketing. I ended up selling the company to Yahoo! in 1998 and have been doing what I do now ever since. That’s a long answer to your question.

No, that’s great. Was creativity a part of your childhood?

Well, you know, semantics matter a lot when you have conversations like this. I think “creativity” is better described as failing repeatedly until you get something right. I was encouraged by both my parents—my mom, who had a background in the arts, and my dad, who comes from both business and the arts—to always be putting on a show, doing an experiment, or trying something new, so I was failing from a very early age.

In terms of creativity, the really formative thing that happened to me is that I started teaching style canoeing in Canada at a very old co-ed summer camp in a national park , which I still do every year—I’ve been doing it for 42 years. What I discovered is that if you’re in a situation where people don’t have to engage with you—because at this camp they could do anything they wanted—you have to figure out a way to attract them. The number one way I found to attract people was to help them connect with their dreams. And so, when I was 17, I started a cycle of creative ways to put on enough of a show in front of people that they would choose to engage in that to achieve their dreams. I’ve basically been doing the same thing ever since, except that there are no canoes in New York City.

Did you have any “aha” moments along the way when you knew that this was what you wanted to pursue, especially pertaining to what you’re doing now?

Well, when I was running Yoyodyne, we actually hired someone whose job was to get speaking engagements for me. I never got paid to speak; sometimes we even paid to get me on the stage. I found out a few things from that experience. First of all, people give an unfair amount of credibility to someone who is standing on a stage or who is writing a blog or has written a book or otherwise put himself in front of them. If you use that credibility as a force for good, you get to do it again. I always knew that, unlike most people, I was willing to fail on stage. When I first spoke at InternetWorld, I was the 423rd ranked speaker; the next time I was 200 and the year after that, I was first. I didn’t get there by getting better at the way I originally set out to do it. I got there by making the mistakes that other people weren’t willing to make.

“The desire that we have to do something that’s never been done before means that the people who are around you generally will not encourage you to do it…if they were encouraging you to do it, then other people would be doing it already and it wouldn’t be unique.”

You mentioned earlier that you had a mentor. Did you have any other mentors along the way and how did they inspire you?

I’ve written a post about mentors and heroes and I want to be really clear about this: I think that heroes are more important than mentors. A hero is somebody who you can emulate; somebody who raises the bar for you. Heroism scales, so one person can be a hero for a lot of people. Mentoring is over-rated in that there’s this myth that they will pick you, cover for you when you make mistakes, encourage you, and be at your side until you become your true, best self. There are very few of those relationships in the world.

The guy at Spinnaker I was talking about earlier is David Seuss. What David did for me on probably six occasions over two years, was step in when I was screwing up and encourage me to screw up more. He didn’t sit me down and teach me how to write or do marketing. I don’t think he was great at either of those things. What he did that was extraordinary was that he looked at people around him and said, “Just try again.”

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do? Who has encouraged you the most along your creative path?

I think that the most important work that most of us do when we’re being creative is not supported by our family or friends. The ridiculousness of the Olympics that is going on now—it takes zero bravery to win a gold medal in swimming because all you’re doing is trying to go 0.1 second faster than you went yesterday. It’s a linear problem that goes from A to Z, in a straight line, and everyone is cheering you on every step of the way. Sometimes you might be ready to give up because you don’t think you’re good enough, but there’s no one saying, “Don’t go that direction. That direction cannot possibly be achieved.”

The desire that we have to do something that’s never been done before means that the people who are around you generally will not encourage you to do it. Because if they were encouraging you to do it, then other people would be doing it already and it wouldn’t be unique.

Was there a point or points in your life when you decided you had to take a big risk to move forward?

Oh, yeah. I’ll give you a couple of examples. When I finally had my book packaging company working after seven or eight years of struggling, I had ten employees and we were finally making a profit. Two-thirds of our revenue came from one company and they were jerks. They were making our lives miserable and what we were becoming was the kind of company that was good at working with difficult clients. I didn’t want to become that kind of company, so I fired our biggest client—the one who accounted for more than half our revenue. I said, “Here. Here’s the project we spent four years building. You can have it. Keep it.” It could have wiped us out, but instead, the group was so energized that they made up all the revenue in the next six months.

Here’s another example. After I did Permission Marketing, it had become a bestseller. I could have sold my next book for plenty of money and done it the same way. That’s not what happened, though. After I wrote Unleashing the Idea Virus, I thought I would be a hypocrite to release a book about how ideas spread if I wasn’t willing to spread the book. I walked away from Simon & Schuster and said to the world, “Here, take my book. It’s free.” That felt pretty risky at the time.

It’s risky when you get up on stage and throw out five years worth of slides, anecdotes, and things you know work and start again—I did that for a group of 12,000 people a few years ago. That was really scary. It’s one thing to fail in front of 100 people, but once the room is so big that you can’t see the people in the back row, it feels like infinity.

Basically, these are things I’ve survived. I view them as opportunities and I keep looking for them. I keep looking to have enough guts to do something that might not work. The phrase “this might not work” is something I try to say on a regular basis.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I hope it comes through that that’s all I do. You know, there’s the charity work that I do, which I try not to talk about too much. But also, it’s the entire point of what I’m writing and teaching in the seminars that I run and the organizations that I start. I have all the toys and stuff and detritus that I need. Getting more stuff is not what I’m trying to do. I wonder, “Who can I impact today and how can I do it in a way that in four years from now, they’ll be glad I did?”

Are you satisfied creatively?

Not even close. That’s a very dangerous place to be and it would truly depress me if that happened and I would get very scared as well. I think if your goal is for everything to be okay, that’s a mistake. To achieve that goal, the only obstacle you’d have to face tomorrow is to eliminate all risk so that everything would be okay. I’ve made the decision that I’m never trying to make everything okay. I’m trying for there to be more loose ends, not fewer loose ends.

Do you have anything you plan to tackle in the next 5 to 10 years?

By my nature, I see the world in shorter cycles than that. The Internet has made it worse and fueled everyone’s desire to see things in shorter cycles. I can’t even visualize what the world is going to be like then, even though that’s one of the things I write about. I think that’s a failing of mine that I can’t tell you that I have some secret plan that’s going to be ready in ten years.

(all laughing)

If you could go back and do one thing differently, would you and if so, what would it be?

No, I would not change a thing because if I did, I wouldn’t be me and I’m really glad to be me. There are a hundred things I regret; there are 75 things I could do over, but I wouldn’t because that would mess up what I ended up with.

Related to that question, I will tell your readers that even if they don’t like science fiction, there’s a book called Replay by Ken Grimwood that will stick with them for the rest of their lives and I encourage them to read it.

“I think if your goal is for everything to be okay, that’s a mistake. To achieve that goal, the only obstacle you’d have to face tomorrow is to eliminate all risk…”

If you could give one piece of advice to someone starting out, what would you say?

This is easy. There’s a picture that I just saw online two days ago. Monday I have this seminar I’m running for free for college students and I’m going to show them this picture before we start. It’s a picture of someone graduating from college. You can’t tell, but you can guess that they’re probably $150,000 in debt. Written on the top of their mortarboard with masking tape it says, “Hire me.” The thing about the picture that’s pathetic, beyond the notion that you need to spam the audience at graduation with a note saying you’re looking for a job, is that you went $150,000 in debt and spent four years of your life so someone else could pick you. That’s ridiculous. It really makes me sad to see that. The opportunity of a lifetime is to pick yourself. Quit waiting to get picked; quit waiting for someone to give you permission; quit waiting for someone to say you are officially qualified and pick yourself. It doesn’t mean you have to be an entrepreneur or a freelancer, but it does mean you stand up and say, “I have something to say. I know how to do something. I’m doing it. If you want me to do it with you, raise your hand.”

The two of you didn’t get a call from Rupert Murdoch asking you to start this cutting-edge interview series. You didn’t. And it might not work, right? But it’s way better than watching Saturday morning cartoons.

Yes, it is. (laughing) How does where you live impact your creativity?

I think there are a few cities in particular where someone might be exposed to enough change and noise that their creativity goes up. But in that very same place, there are people whose creativity goes down because the noise drowns out the sound in their head. My friend, Zig Ziglar, quotes a statistic from a study which found that a huge percentage of people who moved from Houston to Dallas started a successful business in the next year. He then tells people that before they quickly move from Houston to Dallas, they should understand that the study also shows that the same percentage of people who moved from Dallas to Houston started a business. The point isn’t where you live; the point is how it feels to live there. I don’t think it’s in the water or the air; I think it’s in the choice of how you see what’s going on around you.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Some of my most creative moments have come being part of organizations that were filled with energy and forward motion. The examples are the team at Yoyodyne; the circle of a hundred people that Fast Company assembled, which was called the Advance; the team of a dozen people who ran Spinnaker; and the software company where I had my very first job. Those were magic moments when I felt like I had to raise my game to keep up with what was going on around me and to keep up the promises that I had made to extraordinary people. Perhaps the most selfish thing I’ve done in the last five years is not sign myself up for something that scary and audacious on a daily basis and I think it’s because I’m getting older and I don’t think I would do my best work in that frantic situation.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Ha! There isn’t one. That’s on purpose. If you have a typical day, I think that that’s something you should work on.

What are you listening to right now?

Well, there’s an enormous amount of media in my life. To the right of where I am sitting is a completely American-made analog stereo with a record player, a ModWright amplifier, two small monitor speakers made in California, which are connected by this funky wire, and on the record player is a 45RPM LP of Muddy Waters. It’s been on there for a long time and before that, there was a Charlie Parker record on repeat. I listen to a lot of Keller Williams, who is a friend and brilliant musician, and I listen to the Grateful Dead channel in my car when I’m not listening to Radiolab.

I find that I don’t have patience for the typical audiobook because the reader doesn’t read fast enough for me. There are certain audiobooks that I listen to on a regular basis over and over again. They are Ben and Rosamund Zander’s The Art of Possibility; Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art, Do the Work, and his new book, Turning Pro; and Zig Ziglar’s Secrets of Closing the Sale. I know more than a hundred hours of Zig Ziglar’s work by heart having listened to it over 500 times.

Do you watch any TV shows or have any favorite movies?

I got rid of my TV the day Seinfeld went off the air. I haven’t watched live television since then, except in a social setting where someone else needs to watch it. I used to watch The Sopranos on DVD on airplanes, but then I noticed that people were looking over my shoulder. Sometimes in The Sopranos there are strippers and so, oh my God, wait until that gets on Twitter—Seth’s watching porn on airplanes. I quit watching it, so I don’t know what happens at the end.

I don’t like the travel that comes with my job and the treat I give myself after a talk is that I watch one episode of the trashy USA Network show called Suits. It’s completely divorced from reality and has a cliffhanger every six minutes, which makes an hour of the flight disappear quickly.

Do you have a favorite book?

As a book packager, what we would do is buy every book on a topic when we wrote about something. I used to have 3,000 books in my old office. When I moved to my new office, I gave away 2,500 of them and I miss them every day—not because I opened them, but because looking at them reminded me of what was inside.

You know, I don’t know how to pick one book. I tend to read mostly non-fiction leavened with trashy fiction and science fiction. Back when Neil Stephenson was good, Snow Crash and The Diamond Age were two of the best books ever. I probably read four or five nonfiction books a week—everything from The Peter Principle, which I started reading 35 years ago when I was just a kid, to books that have shown up lately that make me sit up straight. Kevin Kelly is three for three; his new book, What Technology Wants, is an absolute must-read and will change the way you see the world.

What’s your favorite food?

I eat the same thing for breakfast and lunch pretty much everyday. Breakfast is an almond milk and hemp shake with a banana, dried plums, and walnuts. Lunch is quinoa with arugula from Yuno—she owns a stand at the Union Square farmer’s market—and rice wine vinegar, chickpeas, and an egg from Tellos Farm.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Well, one option could be that I’m the guy who never dies and 400 years from now, everyone is amazed that I’m still alive.

(all laughing)

I think the goal I have in my work is not to be remembered, but for the people who use the work I did to be remembered instead.

“I think the goal I have in my work is not to be remembered, but for the people who use the work I did to be remembered instead.”