- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker October 2, 2012

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Jason Santa Maria

- designer

- developer

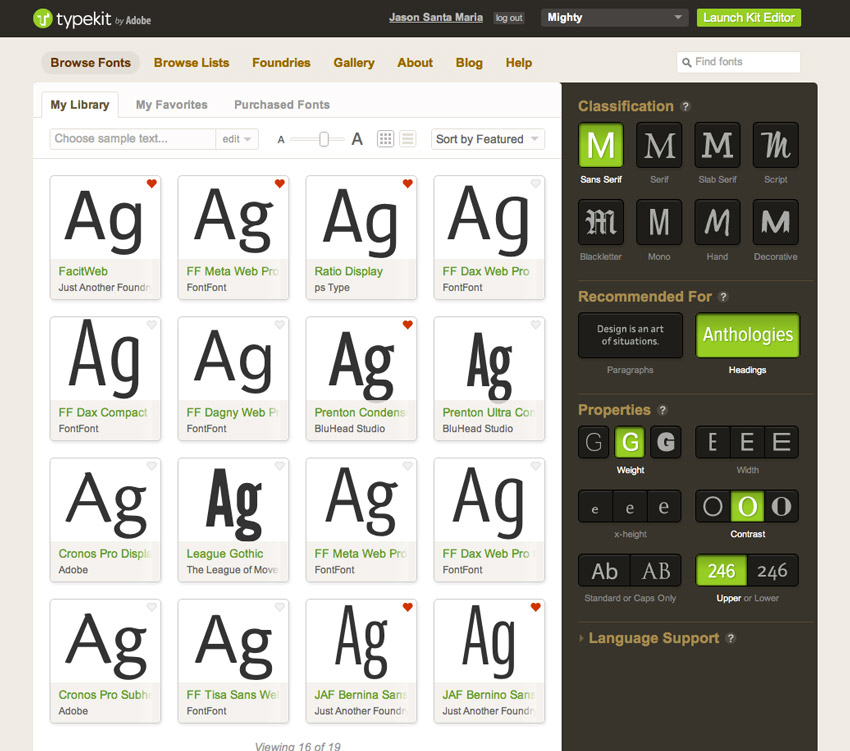

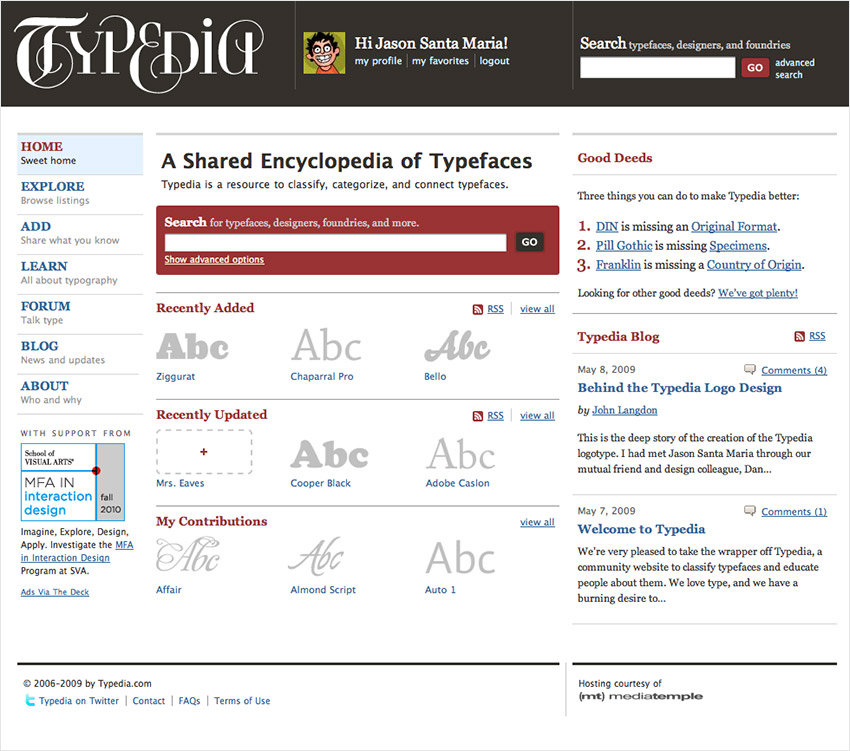

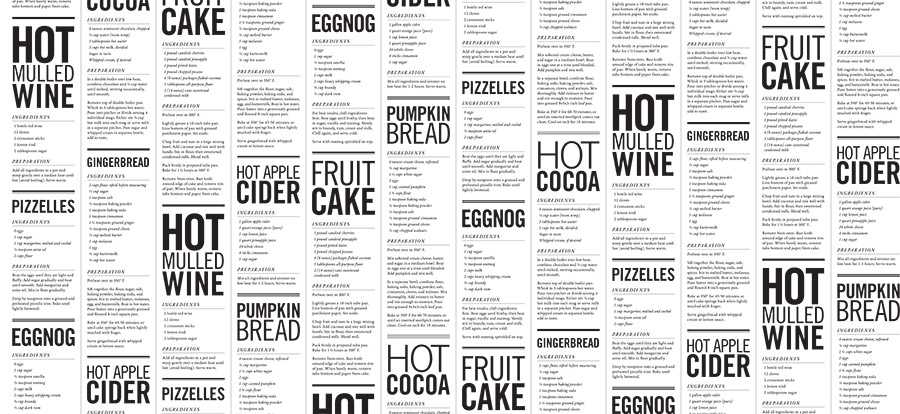

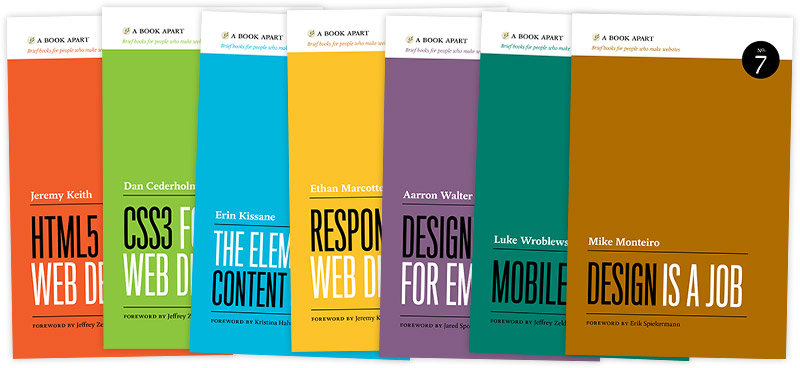

Jason Santa Maria is a Brooklyn-based graphic designer and the founder and principal of the design studio, Mighty. He is currently creative director for Typekit, a faculty member in the MFA Interaction Design program at SVA, co-founder of A Book Apart, creative director for A List Apart, and founder of Typedia. He has worked for clients including AIGA, the Chicago Tribune, Housing Works, Miramax Films, the New York Stock Exchange, PBS, the United Nations, and WordPress.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming a designer.

It all started when I was a kid. I drew a lot and my parents and grandparents, who my parents and I lived with, were very supportive. They constantly tried to nurture any inherent ability I might have shown for drawing. At the time, I was drawing wilderness scenes; later, I would draw comic books and superheroes. Not only did I like to draw, but as I got older, I thought that perhaps I could do something with it as a career. Since I really liked drawing comics, I figured I would go to school, become an illustrator, go on to draw comic books for a living, and make millions of dollars.

I was a very, very poor student and barely managed to get into college. I only applied to one college based on my brother’s recommendation—Kutztown University. It was a good art school and wasn’t very far from where I lived in the suburbs of Philadelphia. They didn’t have a portfolio review, which worked out to my advantage because I didn’t have a portfolio. Instead of a portfolio review, they issued an art test—it was a few steps up from the draw the pirate head and turtle test on TV—and I somehow managed to pass the test and get in.

The Illustration program at Kutztown was actually combined with the Graphic Design and Advertising programs in the first two years. All students took foundation courses, like Life Drawing and 2D Design, before taking classes in their concentration. As I worked my way through foundation classes and some illustration courses, I realized that I wasn’t cut out to be an illustrator. I wasn’t nearly as good as others in my classes and I also discovered that my heart wasn’t in it.

Around that time, I met more and more people who were concentrating on graphic design, like my friend, Rob Weychert. I liked the work they were doing and began to think graphic design might be a viable option for me, although it was also very foreign to me because it was done on the computer—up to that point, I had never owned a computer.

Tina: You had never done any work on a computer?

No. None whatsoever. My family had a computer, but it was mostly for typing out papers and I didn’t really know how to use it. It certainly wouldn’t have had any design programs on it. It wasn’t until college that I really got acclimated with the computer and later, owned one.

Tina: That’s amazing. See, it’s never too late.

Never.

From there, I changed my major and concentrated on graphic design. I still minored in illustration because I couldn’t entirely leave it behind and I realized that many of the skills I learned in illustration courses helped me to be a better designer.

I mentioned earlier that academically, I was a poor student in high school. I carried my poor grades from high school over into college. However, after transferring into the Graphic Design program, I suddenly started to become a good student. I got my first “A” and realized, “Oh my god, I can actually do this.” I threw myself into design and developed a deep, deep love for it. I spent all my time reading and trying to make as much work as I could.

Toward the end of my college career, an Intro to Web Design course was offered during the summer semester. I happened to already be taking some summer classes, so I took that one, too. That was my introduction to working on the web—before that, the Graphic Design program was entirely print focused. I didn’t know anything about making websites, but that class gave me the opportunity to play and work with this new medium. Being able to make something, put it online, and allow people to view it within minutes was really exciting and interesting to me.

That’s my story through the college years.

(We take a break to eat our delicious Peruvian chicken—it was good!)

What happened after college?

I went to college for 4 1/2 years, but completed most of my credits during the first four years. I spent my last semester finishing up a few credits and heavily working on my portfolio so I could start looking for jobs before graduation. I did a couple interviews and was hired at an agency just outside of Philadelphia. I got my foot in the door there because of the print design I had done in school, but the agency was evenly split between print and web work, which allowed me to continue learning the web. I stayed there for a few years and eventually rose to an art director role. Then I worked at a different agency for a few years and although the people there were fantastic, the experience was unremarkable. Around 2005, I left and started freelancing.

While I was freelancing, I started doing work for Jeffrey Zeldman and we really hit it off. We started working together more and I eventually came on board full-time with Happy Cog. I worked remotely from Philly with Jeffrey and then Greg Hoy assembled a group of people and launched the Happy Cog Philadelphia office. During that time, I served as a creative director in both offices for a few years before moving to New York to work more closely with Jeffrey.

As one might imagine, I burned out after a few years and when I left Happy Cog, I was unsure if I wanted to keep doing client work at all. It wasn’t the pace or the work itself that got to me—I loved both of those things—but I felt like I was getting too comfortable and complacent creatively. I needed to shake things up, so I decided to try some different non-client things and see if anything stuck. I took a position with a little startup called Typekit, which was run by some friends out in San Francisco—Jeff Veen, Bryan Mason, Ryan Carver, and Greg Veen—and I started working on side projects. I launched Typedia, co-founded A Book Apart, and began teaching in the Interaction Design MFA program at the School of Visual Arts.

Did you have a specific “aha” moment when you knew that you wanted to focus on design?

I would like to say there’s a glamorous answer, but there’s not—it’s more of an embarrassing answer. At the time when I was in school, design was going through a phase where it was very grungy and deconstructed; those were the days of Ray Gun magazine and heavily used Emigre fonts. I observed what people were doing and noticed how things looked collage-like, thrown together, and dirty. Something about that appealed to me because it was attainable. When you’re starting out, you can’t achieve perfection in your work. There are always really evident seams in what you do, but when it’s supposed to be rough, you can feel like you’re fitting in very quickly. The bar seemed like something I could reach at the time because design was going through this odd phase. Over time, once I started to better understand design, I realized how that style was useful to get me through the door, but not useful as a means to an end for me. That was probably my big “aha” moment.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

One of my biggest mentors, whether she knows it or not, was a college professor of mine named Elaine Cunfer. She was the first teacher who I ever got an “A” from. It was a very simple gesture and I was trying really hard, so I probably earned it. Once I got it, I realized I could succeed and that changed things for me. I began to try harder and engage more with her and my other professors.

I also mentioned my friend, Rob Weychert. He would never take credit for this, but he’s the one who really introduced me to design. More than anything, the times I popped by his dorm room and watched over his shoulder while he was working got me thinking about design.

And then there’s my grandfather. He built houses and was a fantastic man and craftsman who taught me how to work with my hands and build things. He was very supportive of my crappy drawings when I was a kid and his enthusiasm pushed me forward.

You already talked about your childhood, but was there anything about it that was especially creative?

I grew up in the country in Pennsylvania and there was no shortage of things to get into trouble with. What I take away from that is that I was a really imaginative kid. I’m sure that I’m romanticizing it as I’m getting older, but when you’re a kid, everything seems possible. When you think about doing something, the time between thinking about doing it and actually doing it is usually very brief. You say, “Hey, what if I do that?” and then you’re doing it. As an adult, you think, “I want to do this thing,” or, “I want to make something.” Then you start gathering resources and devising a plan, but then you get tired because you’re old and want to lay down. There’s something about that childhood idiocy that I often think back on and love.

Ryan: Why do you think we lose that?

You know what injuries feel like when you’re older. You know what emotional injuries feel like and you know what physical injuries feel like. When I was hurtling down a hill on a skateboard as a kid, I didn’t think about the possibility of wiping out and what would happen after that. As you get older, you can very vividly imagine the consequences.

Ryan: I wonder if that’s a good or bad thing.

Oh, definitely a good thing. Once you’ve been hurt, you understand what being hurt feels like. It’s good because it makes you more cautious and analytical, which is really valuable. The sum total of big decisions that you need to make as a kid are minimal. Once you are out in the world and in a career or a serious partnership, the decisions you need to make on a daily basis can affect you in big ways.

That’s very true. Was there a point in your life when you decided to take a big risk to move forward?

The biggest risk I took was when I left the security of an agency job and went out on my own. I didn’t know anyone who was doing that at the time and I didn’t know if I could do it. I didn’t know anything about business; I just jumped in with both feet and hoped I would figure it out. I read tons of books and crossed my fingers that nothing bad would happen or that if it did, I could weather the storm. It probably wasn’t until a few years into freelancing that I actually started to feel comfortable with it.

Tina: How long have you been freelancing?

Since 2005, but I’ve done very little freelance work on the side since I started working full-time at Typekit.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Oh, yeah! Everyone has been so supportive and is really into it. I hang out with a lot of friends who are designers, so of course they’re supportive. My family has always been into what I do. They don’t always entirely understand it or get what I’m talking about, but they do know that I’m making decent decisions and doing something I love.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I always have. The default posture of the Internet is that you put work out and hope that someone connects with it, learns from it, and builds upon it. That isn’t unique to the web community, but it’s one of our community’s greatest traits—everyone shares what they do and we all learn from one another.

From the beginning, whenever I was in a position to tutor or mentor someone, I was always up for it. I want to leave a mark in a way that helps other people to be better and if I have knowledge that can do that, I think I have to share it. By doing so, it sets an example for others to do the same. It pays it forward and helps foster a better community.

Tina: It’s interesting to me that you’re teaching because you talked about struggling academically for the better part of your time as a student. Now you’re able to help others connect with what they’re learning.

I’ve never thought about it in that way, but it’s true. Once I figured out how to unlock what’s useful in school, I wanted to do that for other people, too. That’s not to say I’m good at it; I’m an okay teacher. It’s something I want to be good at, but it’s going to take some time.

Are you satisfied creatively?

Yes and no. I can say I’m happy with the things I’ve accomplished, but I’m always looking forward to the things yet to come.

Are there things that you want to tackle 5 to 10 years down the road?

One of my greatest fears is being at a big company and rising through the ranks to become a manager of people. That’s an art and there are people who are really good at energizing others and getting the best work out of them, but the thing I most enjoy is being hands-on and seeing something through to the end. I want to keep making things and not just talk about making them.

I like making and continuing to nurture something. The thing that always threw me with client work was that I would propose a solution—sometimes based on experience or sometimes an educated guess—but it might not be the best solution. I made something, gave it to the client, and it became theirs—all the problems became theirs, too. Something about that felt disheartening to me and I often struggled with it. When you are your own client and are able to keep iterating, you can revise something based on the way it’s being used and the feedback you’re receiving. You can improve it and make it the best it can be for as many people as possible. There’s something really wonderful about that; that made me fall in love with design all over again.

I also find myself being more interested in hardware. I’m fascinated by the act of reading and where books might go next. What lives on with the things that we write and how do we get it into people’s hands in a meaningful way? The way we’re doing it now with iPads and Kindles doesn’t feel right. That’s not me lamenting for print books, but I think there should be a larger connection that we’re missing with words beneath glass.

If you could go back and do one thing differently, do you think you would?

I don’t know. The good things I’ve done, and even the mistakes I’ve made, have led me to where I am today. If I hadn’t done those things, I might be a different person. I wouldn’t change anything big; I would change some of the little things. For example, when I left my first job, I ended up in a fight with my employer—it was over something stupid and I was just a snotty kid.

If you could give one piece of advice to another designer starting out, what would you say?

Creativity is like a muscle and you need to exercise it constantly. You need to draw; you need to sketch; you need to constantly be recording and taking in the world around you. A lot of writers say they need to write in order to understand how they think; I believe designers need to draw to understand how they think. Keeping a sketchbook is something that every designer I know takes for granted. Because it’s something they can do, it’s something they don’t do. It’s such a vastly empowering and useful tool to get ideas down on paper and cycle through them quickly. It’s the most useful visual thinking tool that we have at our fingertips.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

Well, I live in Brooklyn. I know that if you don’t live in New York, it’s very easy to look down on NY and think it’s a hipster place and everyone is really full of themselves. When I moved to NY and fell into Studiomates, it created a family for me, which showed me that everyone here is so kind and so creative. Those people drive me forward. I see what they’re working on and it makes me want to be better and work harder. The people around me are what makes this place so great—it impacts me on a daily basis.

It sounds like being a part of a creative community of people is something that’s important to you.

Yes. When I first started freelancing, I worked at home by myself and it took a lot of willpower and energy to do regular things—to get out of bed, shower, eat breakfast, and not watch TV or do easy chores around the house all day to feel a sense of accomplishment. Being part of a community in the studio setting and getting out and meeting other designers and artists is important. Here, there is such a density of people with creative pursuits in different disciplines; I may not have been exposed to that otherwise. This is a very enriching place.

Ryan: Do you think routine is important to the creative process?

Absolutely. So many writers I know say they get up and no matter what, they write for three hours every morning. They have a regimen and consider art and creative pursuits to be work, which they are. Chuck Close says, “Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work.” You just have to put your nose to the grindstone. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t, but waiting for inspiration to strike isn’t going to bring it about any sooner.

With the way my schedule has been in recent years, I find myself following the momentum of things I’m interested in. I might wake up and know that I have a deadline, but if something really strikes me, I might chase that down because that’s where my interest and energy is at the moment. I’ll probably be able to work through it a lot faster and then I can move on to what I need to do next.

That brings us to our next question. What does a typical day look like for you?

I wouldn’t say there is a typical day. Because I’m involved in a variety of things, whatever is making the most noise at any given time gets my attention. Some days I might work on Typekit stuff all morning because we’re trying to push out a feature; or I might update the A Book Apart website; or monitor some postings on Typedia; or email back and forth with students or potential clients. And I also travel and speak.

You are a busy guy! What are you listening to right now?

I’m listening to one band way too much right now and I apologize to anyone who follows me on Rdio. My friend, Rob, introduced me to a band called Wussy. They’re from Cincinnati and wow!—I just can’t stop listening to their albums.

Any favorite movies or TV shows?

I’m sure the stock answers are shows like Arrested Development and The Wire, which are really fantastic.

My favorite movie is Miller’s Crossing by the Coen brothers; it’s phenomenal. I’m also a really big horror buff and love the classics—Alien, Jaws, The Thing—but I also like lots of campy stuff and everything in between.

Favorite book or books?

I read a great deal of fiction, but I also read a lot about process and design. There are two books in that category that really affected me and I reread them often. They are Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott—

Tina: I love that book!

That book really changed my way of thinking. It’s about writing and although I’m not a super writer, I try and that book made me want to get better. So much of what’s in that book can really lend itself to any creative process. The chapter called “Shitty First Drafts” is amazing. It’s about putting things down on paper and getting the crap out of your head so that you can start revising. It was because of that book that I came around to this belief that it’s often much easier to revise than to create.

The other is Hillman Curtis’ book, MTIV: Process, Inspiration and Practice for the New Media Designer. It’s about craft and inspiration and offers a very personal account of Hillman’s process. I read it a few years back when I was still in my formative years as a designer and it changed the way I thought about design. It was very enlightening.

What’s your favorite food?

Probably pizza. New York is a good place to get it because there’s an absurd amount of pizza here. Or my mom’s meatballs. She would leave them cooking on the stove all day and I swear you could hear everyone’s stomachs rumbling throughout the house. I also can’t help but grab a cheesesteak every time I’m back in Philly.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

We all have the opportunity to pay it forward and we’re all part of a greater community. That said, I hope that people learn something from what I did and that because of that, they’re able to help others learn.