What was it like to grow up in South Korea? How did your childhood influence your ideas about creativity?

My mother and father met in Jinju, which is a small town in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula. Both of my parents were boomers after the Korean War and didn’t finish college, but they helped me and my younger brother get an education—that’s some of their mindset. My father was a car mechanic. My mom ran the shop and did a bunch of different work. Both my grandfathers were Korean War veterans. I didn’t really come from a conventional, creative or academic family background. I was more like a little scientist—How does this work and why?

I remember one day a radio didn’t work and I was so curious. Oh, maybe I can fix it. I just opened it up and then put it back [together]. I just really liked to interact with the physicality and then how it works, curiosity-wise. My parents didn’t really encourage me, but thankfully they didn’t stop me. What really influenced me from my mom is that kind of mindset: “Okay, you can try it.” Being patient and trusting me. I really benefited from that kind of mindset.

My parents moved the whole family out of their hometown to open a new auto shop about three hours away. No one [we knew] was there. That influenced me too, going to a new city and exploring new things, starting a new business, a new adventure. I saw my parents working really hard, and I learned the importance of work ethic.

So how does a kid from Korea land in the Midwest?

During my senior year, I thought, I want to study abroad. I was still hungry for education and wanted to go to grad school and learn about top-notch design, cutting-edge technologies and aesthetics. My mom also highly encouraged me. She said, “Whatever you do, you will be a better person after the study abroad, even if you become a farmer with a design degree.” University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign gave me an admission and I was so happy. I was like, Finally, I made it! That’s how I went to study abroad in the Midwest.

And right now, I’m teaching at University of Wisconsin–Madison. I applied to this school [as a grad student]; I didn’t get an admission. I like to tell my students this story because, okay, I’m here, I’m teaching you right now, but it wasn’t just one shot from the beginning to the end. Life is not just full of success stories but many ups and downs. You have to deal with challenges, difficult situations, and learn how to navigate them.

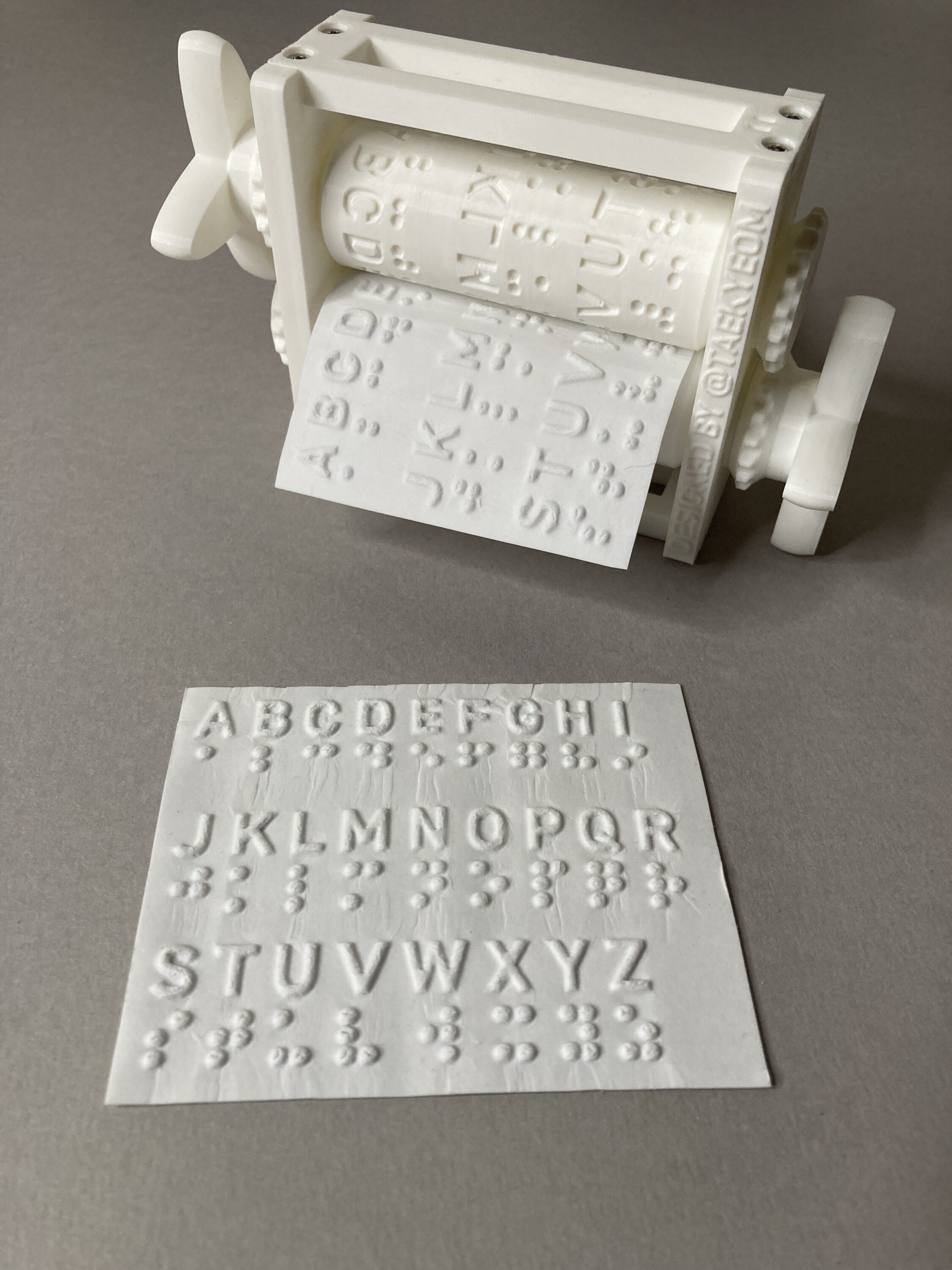

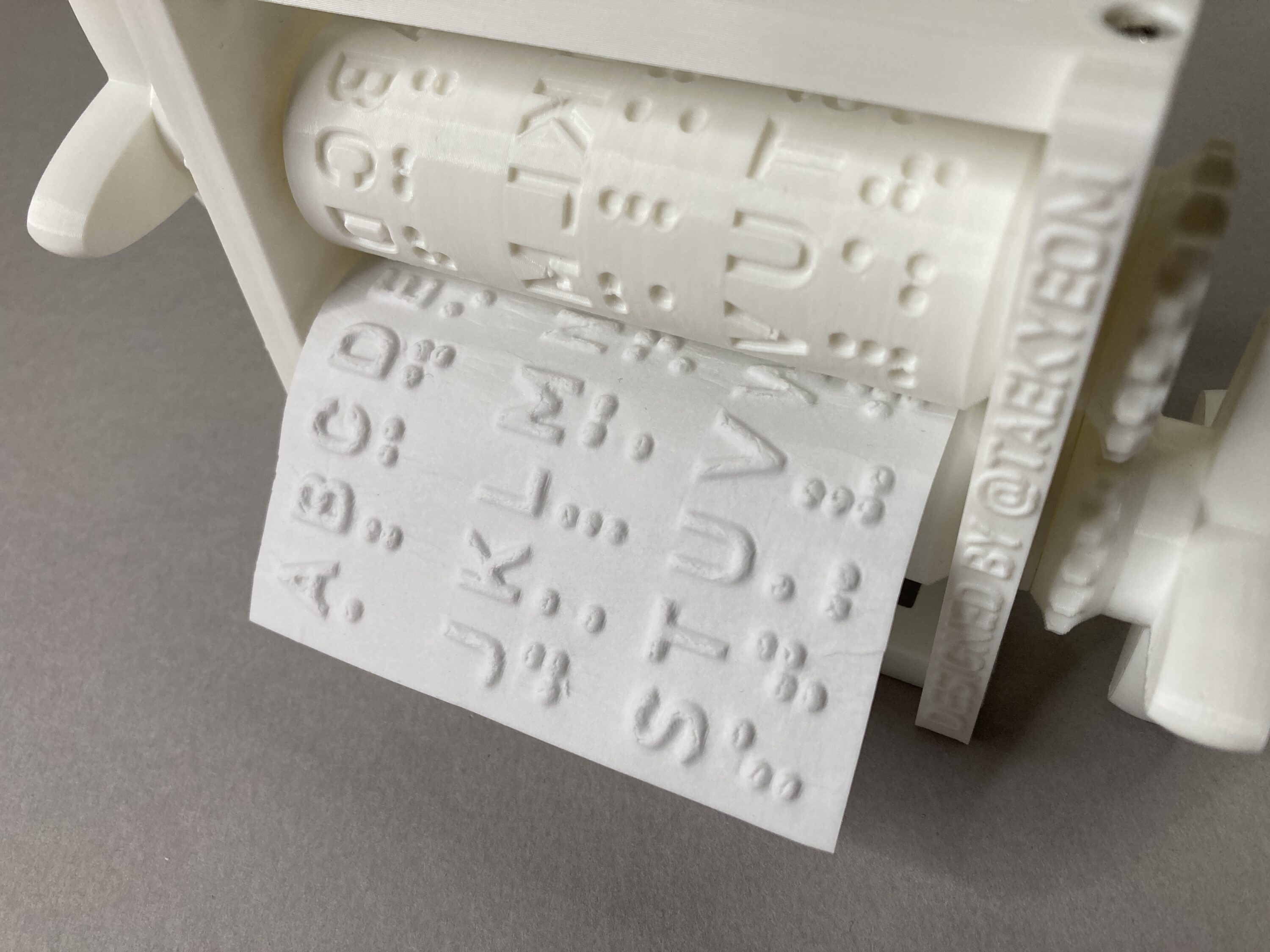

I was thinking back to when we first met. I remember so distinctly that you gave me your business card, I should say you made me your business card, created it right there in front of me with a handheld 3D-printed embosser. It was just the most charming and delightful introduction. Can you tell me a little bit about that device and how you created it?

I am so glad that you remember the moment! The embosser is a modern version of a cylinder seal, a historic artifact invented in 3500 BC to create impressions on wet clay.

In a history class, I learned about cylinder seals—usually introduced right after cave paintings. I made some impressions on the wet clay to test the idea. Then, I designed positive and negative dies, which are perfectly aligned to make an impression on paper. But I cannot carry a clay printer. So I made the 3D-printed embosser.

I designed a bookmark using leftover trim from a printmaking studio for a book art exhibition hosted in Boone, North Carolina. That scrap paper was too good to be thrown away. I thought, Ah, maybe it can be a business card. You’ll see lots of my work will be scaffolding off of some “aha” moment of discovery. And then I try to keep adding. I just love making a lot, testing, playing and making iterations. Now, I use the embosser to score paper for folding patterns.

One of the things that draws me to your work is how you’re exploring mediums that don’t necessarily feel like they would go together. The experimentation, the research, the tool making—how did it come to be?

Many contemporary approaches were started as alternative design solutions with curiosity and the question, what if? I truly believe design is problem-solving. I mean, it can look good, it can be aesthetically pleasing, but technically we are doing something to solve or mitigate problems. For me, most of my work came from curiosity and dealing with constraints. I try not to let challenges and frustration stop me.

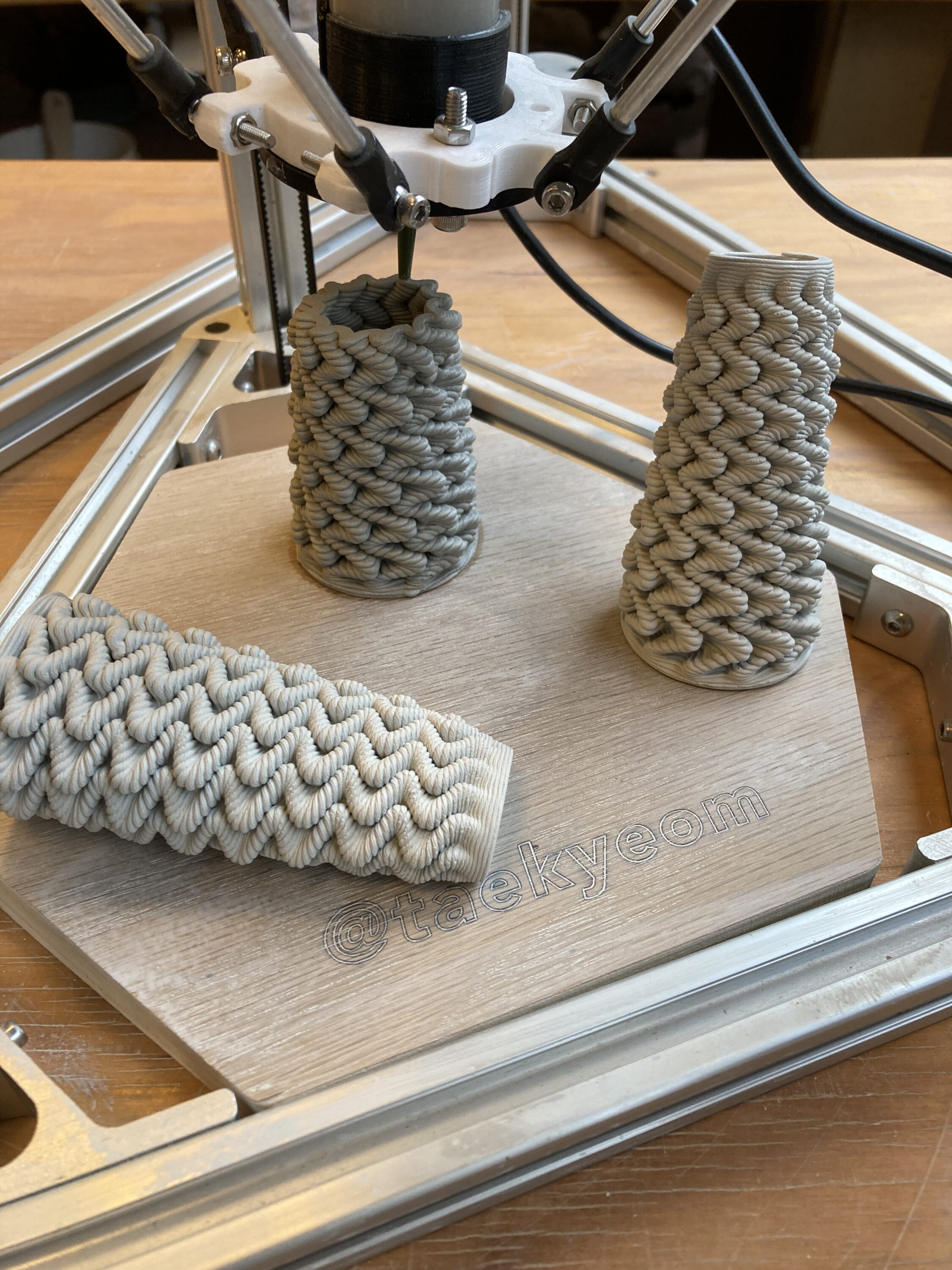

Thinking back to my thesis work, at that time, no digital 3D printing was involved. I did slip casting—making building blocks to create a large modular type. After graduation, I lost access to the ceramic facilities. I couldn’t use the casting table, kiln, everything. I had to be resourceful. I thought, how can I keep working with ceramic material? It was 2015, and people were really starting to use DIY 3D printers. I googled it, and there was an artist creating his own ceramic printer in Belgium. I’m like, aha, maybe I can do that. I ordered a DIY printer. I didn’t think really carefully about how it was going to work, but I said, “Okay, let’s put things together.”

You were experimenting.

Yeah, exactly. The spirit of taking a gadget apart and putting things together. I ordered the part, googled it, and found pieces of information because there was no manual to teach me. I just did it by filling the gaps. Bring things together, take it apart, test it, and iterate it. Do it, working. Do it, not working. Move to the next step. It’s an extensive trial-and-error process and each step fuses new ideas and solutions.

What’s fascinating is that you brought together digital fabrication and these handcrafted techniques.

I did not formally study either ceramics or 3D printing. I’m not the first one who created this ceramic 3D printer. I can claim that I’m the first graphic designer who put together a DIY ceramic 3D printer for graphic design work. I can be proud of that. Again, it’s not what I initially intended to do. I just moved toward that direction and explored the graphic design tactility with typography as well.

When I was in graduate school, my thesis project was supposed to be an experimental typography project with various found objects. I was a second-year student when I got retinal detachment—one day, the retina in my eyeball detached. When it happens, your vision gets blurred, and you see some shadows, and eventually, you can lose your vision. So, I go to the ER and get surgery. It detached again, even bigger and required a second surgery where they injected a gas bubble [into my eye], and it was scary.

I had to go through the recovery, facedown, 24/7 for about three months. During the recovery, you cannot breathe well; you cannot sleep well. It was miserable. I couldn’t fly because of the pressure. I’m an international student stuck in the middle of a cornfield.

My friends really helped me, classmates, professors, and even staff members at the School of Art+Design in Illinois. I couldn’t go out and shop, anything. People brought food and water and gave rides to the hospital. It was a life-changing and transformative experience. It really impacted how I work as a graphic designer.

When I got back to school, I needed some sort of therapy while working with design. I wanted to take ceramics class because it’s very meditative, tactile, you have to slow down. One day with my classmate, a sculpture ceramics major, I said, “Oh, this is going to be my retirement plan.” She said, “Why do you have to wait until retirement?” That day, I emailed my thesis advisor: “I want to change my thesis topic.” And then ceramics became part of the work.

How are you bringing ceramics and graphic design together today?

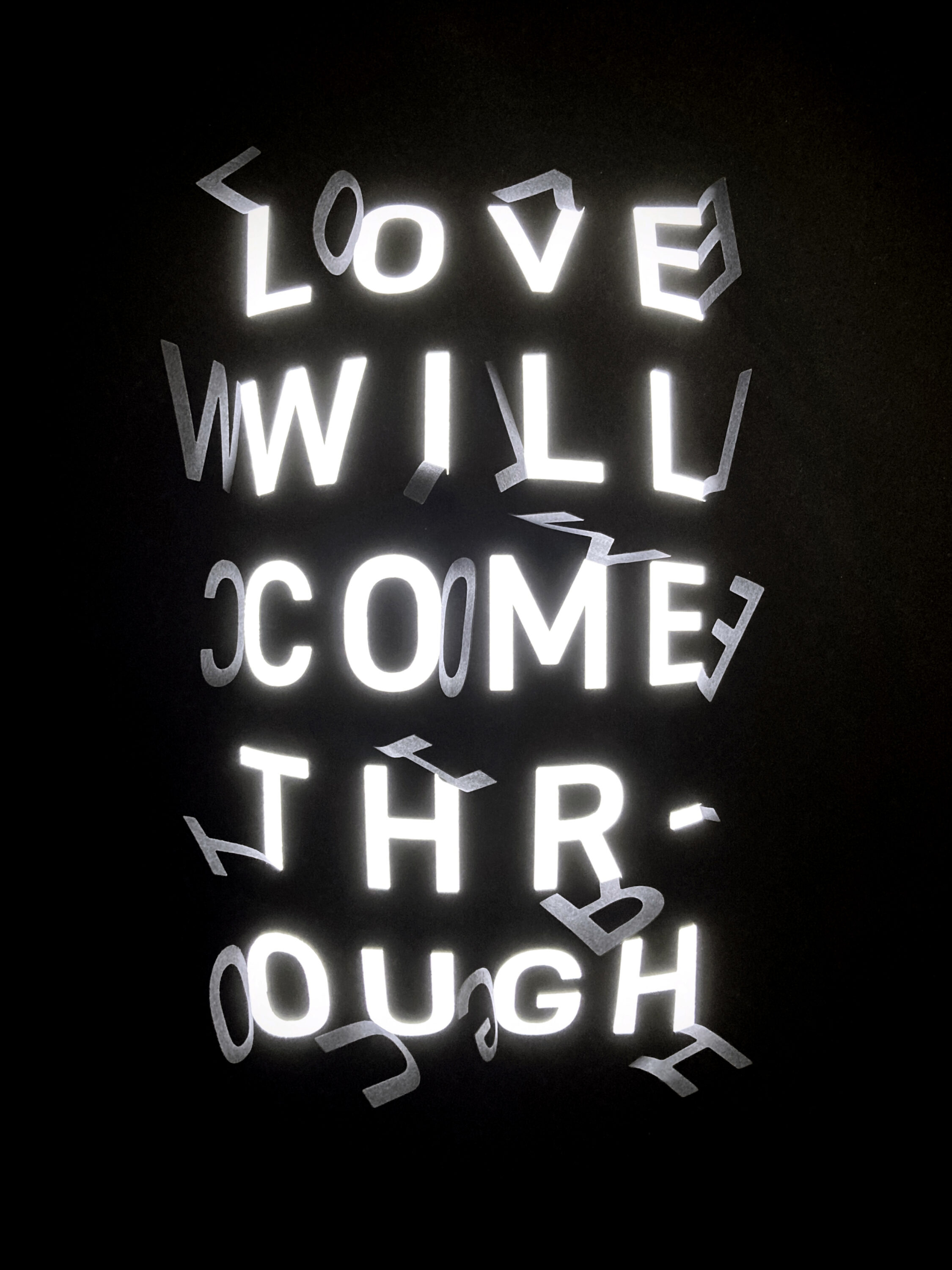

In Ellen Lupton’s book Beyond the Vision, there’s a term called ocularcentrism, which is how, especially in Western culture, we value vision over other senses. Seeing is believing. Going back to my eye surgery, it left me with some vision issues that I am still dealing with. Yeah, vision is good, but actually, my experience has been transformative. Let’s use tactility, it’s [a sense] for most everyone. Ceramics is a very sensitive, interesting material. It’s finicky, you have to know how to work with it. I realized, okay, I’m trained as a graphic designer, but I can work with this.

For my very latest project, I just call it tangible graphic design, it’s my body of work for accessibility and infusing tactility into graphic design. I am proposing some panel talks with other designers using tactility or some kind of experience beyond visual communication. How can we use tactility or other senses? But mainly my panel focuses on tactile communication. It’s beyond vision, beyond written, it’s kind of experiential communication.

It sounds like you’ve taken something that had a very profound effect on your life—physically, mentally, emotionally—and shifted it into something to help inform your work, your daily practice and your research.

What I love to do becomes work, and they are blended together. My full-time job is teaching. So, I wake up, prepare the stuff, and go to school, teach it. I also try to do some writing [in order] to publish what I’ve done. On the days I don’t have a class, I like to play with my 3D printers. I teach undergrad and grad students, but recently I realized that it doesn’t have to be a traditional educational setting. For example, how can I teach you to work with printing or to bring tactility into your work?

Quite a lot of people have an invisible disability, we just don’t know. It can be permanent, it can be temporary. It can be mild, it can be severe. But there are all different types—there’s a spectrum of accessibility and disability. I want to teach these things to my students, how to embrace it, experience it so they can design for a better future. And also, beyond vision, how can we embrace tactility in graphic design? I think that’s what I am trying to do. I didn’t really intend to do this at the beginning, but there’s an English term I really like: trajectory. It may seem I’m just going upward. But when you zoom in, it is always up and down. The most important thing is to keep pushing in the direction you want to move toward.

When you reflect on your creative journey, starting from when you were a student, is there anything you would do differently?

I am full of regret—I wish I did this and Why? But also, at the same time, I learned how to accept the situation. For example, when I didn’t get admitted to the school I wanted, I was kind of angry, but also because of the bad thing I ended up at the school where I met my mentor, my good friends. If I went to the other school, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to meet those people there. What if I did not have vision problems? Bad fortune turned into good fortune. Now I just think, Okay, go with the flow. I’m not a religious person, but I think… we are moving, constantly going through this kind of flow and there are things we can do, but 80 percent is out of our control, I think. Focusing on things beyond our control is unproductive. We can only do a certain part. I’m going to go with it and try to have less bumps. But that’s out of my control as well.

What I’ve learned as an immigrant designer is that creating opportunities is important. If something’s not available, what are you going to do? Screw the idea, move to something else, or wait until someone does it for you? Or you make your own tool, you make your own opportunity. I think that’s the biggest, most important lesson I’ve learned through my journey here. If it is not available, you need to make it. I’m just trying to make some sort of opportunity there.

Tell me about the mentors in your journey.

From my undergrad, Professor Hun Woo Rheem. He is a graphic designer, educator, and author. He wrote a bestselling book in Korea. I learned about creating content, designing, and how to be resourceful and other stuff [from him]. In grad school, I met people who really encouraged me to do other things. And now my mentor, Yeohyun Ahn is my colleague as well; she is helping me to offer a new course. She’s a pioneer in bringing creative coding to graphic design.

I think I’m learning from everyone. I have had many wonderful teachers, and friends as well. If I name them all, we will spend another hour together. One mentor once said, “You’re really like a sponge. Place it in a good place, absorb good things.” I try to expose myself to the good folks and stay away from toxic environments.

That’s related to something I like to talk about too. As an immigrant in the U.S., I didn’t know anyone. Being resourceful, working diligently—that work ethic is the baseline. Everyone, immigrant or not can do that. Then, being resourceful and creating opportunities is a kind of next step. As you do that, you eventually create this good positive chain reaction. What you need is to create a supporting community, a place you feel safe and can make trial and error, and eventually where you can thrive. That’s another thing I am interested in right now, creating some kind of community.

I can relate to that. As an immigrant, you don’t feel entirely rooted in any one place. I looked for those kinds of opportunities, and in the design community there were people, mentors, who really helped me. When I got to the point in my career where I realized that I was starting to be someone’s mentor, it was like, this is what I want to do. I want to give it back.

Exactly. Warmhearted people, making a positive influence. Hopefully, it’s going to create a ripple effect. Giving the opportunity to someone who is underrepresented, who deserves something but hasn’t had a chance to have that exposure. I think that’s also a great act of positive impact as well. Suddenly, I realize, now I’m in the position to share it. Give to people what I received. As an immigrant designer, as a citizen, as an individual, now I need to be generous and create the opportunities, share the opportunities.

There are underrepresented designers and artists doing unconventional work. I just want to tell them, it’s okay. If someone told them, “It’s not graphic design.” Screw that. You can make an argument that it is. You can find a place you feel accepted. For the next decade, I think I feel more responsible for what I’m supposed to do.

I think back to something my professor said. He introduced me to what Laszlo Moholy-Nagy said: Design is not a profession but an attitude. When he introduced this to me in a class, I thought, Oh, that’s such a cool thing. Often, people think designers are just making cool stuff. Yes, that is part of it. But also, design is problem-solving. Yes, that is part of it. And what design really truly is, is an attitude.