- Interview by Tina Essmaker March 31, 2015

- Photo by Jake Chessum

Michael Bierut

- designer

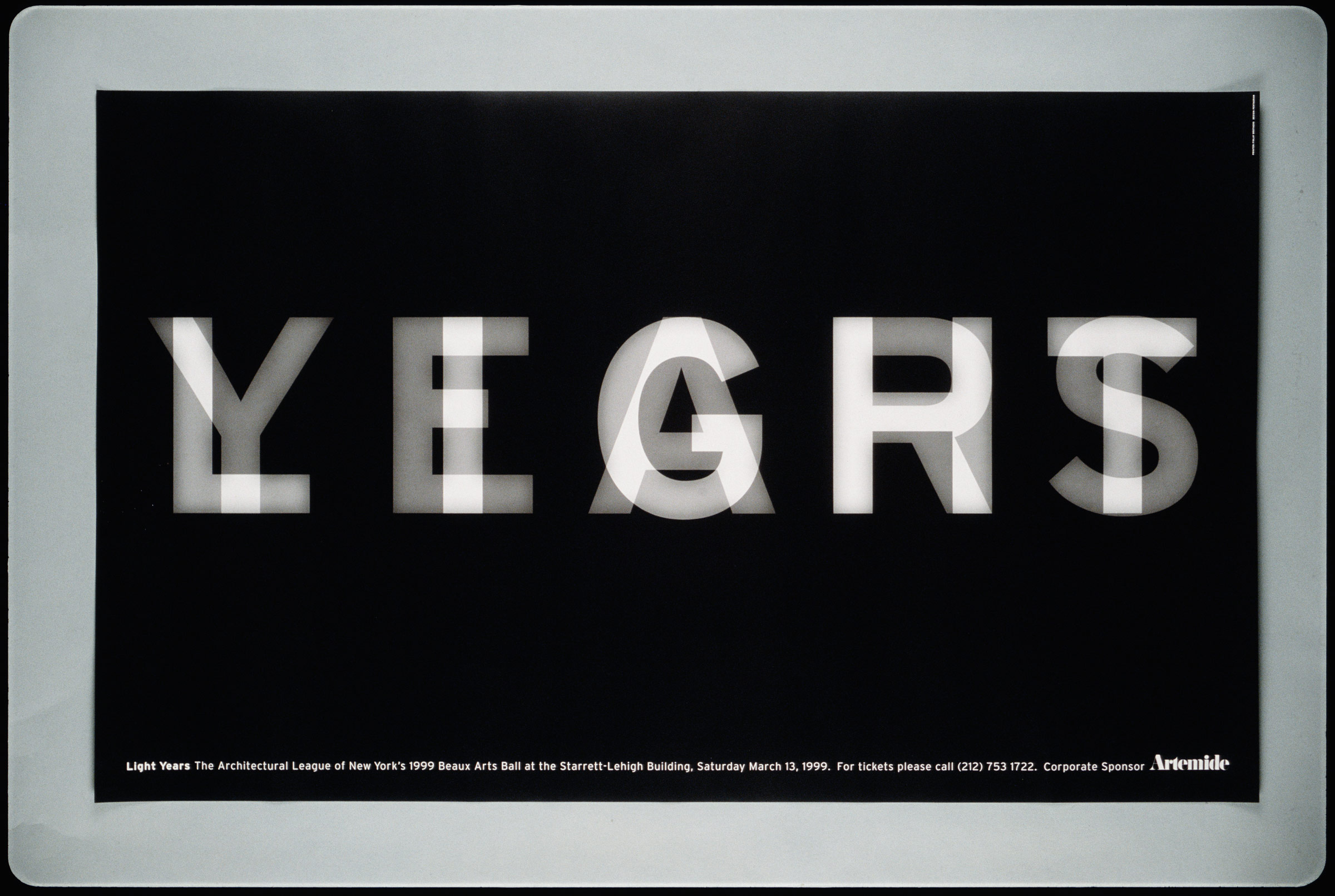

Born and raised in the Midwest, Michael Bierut studied graphic design at the University of Cincinnati. Since 1990, he has been a partner in the New York office of Pentagram. Additionally, Michael is a founder of Design Observer and a senior critic in graphic design at Yale School of Art, where he has been lecturing since 1993. The first book on his work, How to use graphic design to explain things, sell things, make things look better, make people laugh, make people cry, and (every once in a while) save the world, will be published this fall by Thames & Hudson and Harper Collins.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now. I was born in 1957, and I grew up in a working class suburb of Cleveland. As a kid, I was good at art. I enjoyed drawing, but what I really liked about it was that it allowed me to be sociable and meet people. I went to the Cleveland Museum of Art to look at work that I admired tremendously, but I didn’t understand how or why people went off on their own as artists. Why did artists like Josef Albers paint squares or Franz Kline paint big, slashed lines, over and over, all alone? What would possess them to do that?

Instead, I began to admire record jackets and book covers and movie posters. These I understood. I could tell there was some artistry involved, but it seemed more like an opportunity to work on a movie or hang out with a band or talk to an author. It was more integrated into everyday life, and I remember being enthusiastic about that at a young age. I designed little magazines when I was in the third and fourth grades, and I made logos for my friends’ bands when I was in the seventh grade. I could do hand lettering, and if someone wanted an animal in the logo, I could do that; if someone needed a poster for the school play, I could do that, too. I’m still nerdy now, but I was vehemently nerdy at that age. I got good grades, I was a teacher’s pet, and I liked to write. Getting good grades didn’t give me much credibility in the schoolyard, (laughing) but knowing how to draw was something that impressed people. I used art as a sort of magic shield against the bullies who would have otherwise beat me up.

All along, I had no idea that what I was doing was called graphic design. I lived in the middle of nowhere at a time when no one knew anything about something like graphic design. I knew that artists made work in museums, but I couldn’t fathom who made things like logos and posters.

By accident, I happened to find a book in my high school library by a guy named S. Neil Fujita. He’s not a well-known name now, but he designed the cover of The Godfather book. Back then, there was a book series about different vocational adventures with titles like Aim for a Job in Television Repair or Aim for a Job in Dentistry. One of the books in the series was written by Fujita, and it was called Aim for a Job in Graphic Design/Art. I opened the book up, and it was like receiving an instruction manual for my future career: it was all right there. I was about 15 at the time, and I thought, “This is what I want to do.” I didn’t know a single living graphic designer, and no one I knew did anything even resembling graphic design; but all of a sudden, I saw this path. To a certain degree, that was the last big decision I made about my life’s work. (laughing)

I’m 57 now, so that was over 40 years ago, and I actually don’t recommend this sort of fixation as a way of life. In some ways, it’s a blessing. I love what I do, but when I talk to people who came to design by a more circuitous route, I’m a bit envious of them. I also married the first girl I ever kissed, who I’m still married to today, so this type of decision-making is obviously fundamental to my character. Other people have many romances and twisting adventures as they go through their lives. I’ve had one great romance with my lovely wife, Dorothy, and another great romance with the profession of graphic design.

What happened after you discovered Fujita’s book on graphic design? Things escalated quickly after I discovered the magic key that was the term graphic design. I remember going to the next biggest library I knew, which was the regional library near my house. I looked up graphic design in the card catalogs, and there was a book with those two words in the title. The book was called Graphic Design Manual: Principles and Practice by Armin Hofmann.

It was the most bizarre and esoteric book that could have appeared in a small library in Ohio in 1975—to this day, I do not know why it was there. Armin Hofmann, along with Josef Müller-Brockmann, Max Huber, Wolfgang Weingart, and a handful of Swiss designers created the idea of Swiss design as we know it: objective design using Helvetica and minimalist modernism. This book basically outlined the course Hofmann taught at the Schule für Gestaltung Basel in Switzerland. The book is all black and white, and it’s full of exercises, like how to redesign Swiss lightbulb packaging. To me, it was pure gold—it was like stumbling upon a box of Playboy magazines or something! (laughing)

I borrowed the book from the library for months so I could copy pages out of it. Around the holidays, my mom and dad asked me what I wanted for Christmas, and I said, “I just want a book called Graphic Design Manual.” There was no such thing as Amazon, Borders, or Barnes & Noble in those days, so my mom—God bless her—must have called bookstores to find it. Back then, little bookstores didn’t have art or photography books, let alone graphic design books. And they certainly did not have imported graphic design books translated from Swiss-German that no one in the right mind would buy, except for my mom who was purchasing it on my behalf.

But my mom hit the jackpot: she called a big department store in downtown Cleveland and they had it in stock. However, even before I opened it up on Christmas morning, I could tell that it wasn’t the right book; it was too big and too thick. My mom asked, “This is it, right?” When I unwrapped it, I saw that it was the wrong book, Milton Glaser: Graphic Design. If you know that book, you know that it’s the opposite of the Armin Hofmann book: eclectic, colorful, exuberant, and fun. It was all about food, culture, book covers, records, and posters for rock musicians. To me, both books were great, but they may have perpetually confused my aesthetic approach to design to this day.

When I was a junior or senior in high school, I told my guidance counselor, to her dismay, that I wanted to go into graphic design. I had good grades and was college-bound, so I think she had pegged me as a future lawyer or doctor. Again, there was no Internet, so I have no idea how this poor woman found a school for me, but she did. It was the University of Cincinnati, which had an actual graphic design program, and going there meant I could pay in-state tuition.

The program turned out to be super hardcore. At least one of the teachers there, Heinz Schenker, had studied with Armin Hofmann, so he had actually done the lightbulb exercises from the Graphic Design Manual book. I threw myself into the program for the next five years. When I graduated in 1980, a friend of a friend arranged for me to drop my portfolio off at Vignelli Associates, so my first job out of school was working for Massimo Vignelli.

That’s crazy. (laughing) Isn’t it?

“Other people have many romances and twisting adventures as they go through their lives. I’ve had one great romance with my lovely wife, Dorothy, and another great romance with the profession of graphic design.”

And you’re now a partner at Pentagram. How long have you been there? I worked for Massimo for 10 years. I joined Pentagram in 1990 and have been there for 25 years, so I’ve had two jobs.

I’m noticing a trend of long-term commitment here. (laughing) No, no. (laughing) Look: don’t do what I did. I don’t think it’s necessary to have lots of jobs in your career or date lots of people before you get married, but having just one isn’t the only way to do it, either. It’s like when people ask me for romantic advice: everything I know about romance is based on my own limited experience, which is fantastic, and what I’ve seen in movies and TV shows. If people ask me for career advice, I can’t say much outside of, “Take the first job you’re offered and stay there for 10 years.”

Have you had any mentors along the way? You can tell by my account so far that I’m very impressionable; I’m prone to influence. I still have designs that I did when I was 15, it’s clear that my style changed the minute I found the Armin Hofmann book: everything I did turned into flat colors and imitated Helvetica. And when I found the Milton Glaser book, my work started becoming more psychedelic and exuberant. Those guys who I’d never met were, in effect, mentors to me through those books.

In Cincinnati, I had an internship with a great guy named Dan Bittman, and in Boston I had one with the legendary Chris Pullman at WGBH; they were both highly influential. My teachers in school, Gordon Salchow, Heinz Schenker, Joe Bottoni, Robert Probst, Anne Goodman, and Stan Brod, were extremely important. And, obviously, the 10 years I spent working for Massimo and Lella Vignelli left a real mark on me.

Now, I’m partners with eighteen other designers at Pentagram, including seven in our New York office, and they’re highly influential to me, too. We mentor each other to a certain degree, but I learn more from them than they learn from me.

Are there any particular lessons or insights you’ve gained from your mentors that stick out in your mind? Oh, yeah. I can still remember precise moments. When I was at my summer internship with Chris Pullman in Boston during the late 1970s, I was given a little intern project, and I was totally overdoing it. I was trying to combine a little Armin Hofmann, a little S. Neil Fujita, and a little of the last designer I read about. Chris asked me how it was going, and I tried to give an explanation, but it came out horribly. He said, “No, take all this stuff away and start by making it simple.” Chris is a very witty, fun designer and not very doctrinaire in terms of his style, but he always believed that simplicity was the best approach.

When I worked for Massimo, one of the things I learned from him was that you can integrate design into your life. Design wasn’t just a job, or something on your drawing board or computer screen: it was a whole way of thinking about the world. Massimo chose his clients carefully. When potential clients came in, they took one look around the office and knew whether or not it was the right place for them. He didn’t get hired by accident too often: people knew what they were getting into when they hired Massimo Vignelli. The advantage was that his client list was full of people who he was interested in. He was legitimately engaged with their businesses and the cultural context they worked in.

I have to admit that when I first started working for Massimo, I had no class or refinement. (laughing)

How old were you when you started working for him? I was around 22. Back then, it was possible to be a naive 22-year-old in a way that isn’t possible now. When I arrived in New York, everything I knew up until that point was from television or books from the library. There was no way I could have sat at my house in Ohio with my bags packed, looking up Massimo Vignelli on the Internet. So I didn’t fully know what I was getting into. That’s why today is such a wonderful time, actually. Back then, the only advantage was that everyone was constantly surprised. You had to really pay attention and learn from what was around you.

To my credit, I was a real sponge when I arrived at Vignelli, and it was a great place to be a sponge. If you were ready to learn, you could learn very quickly there—both from Massimo and his wife, Lella, who worked closely with all of us. Massimo cared deeply and obsessively about typefaces, kerning, and the space between objects. Every time he sat down to make a three-and-a-half by two-inch business card, it was like no one had ever made one before. He worked it out so carefully and came up with something that he hadn’t quite done before. Then he’d exclaim, “Ahh! Isn’t this great?!” He was so enthusiastic and uncynical and ready to be surprised.

I give Massimo 1000% credit for being my mentor, but I never thought, “I’ll make this guy be my mentor.” I didn’t care if he wanted to be my mentor or not. I attached myself to him like a parasite and sucked out every bit of knowledge and inspiration I could. When people look for mentors, they often think it’s something that’s done to them, but it isn’t. You don’t have to ask permission; you don’t even have to know the person. These days, you can read so much online. I’ve read things on The Great Discontent that make me think, “Oh, shit. That’s true!” And I learn from it. In effect, the person who said it is being my mentor for a moment, even though I’ve never met them.

“When I worked for Massimo [Vignelli], one of the things I learned from him was that you can integrate design into your life. Design wasn’t just a job, or something on your drawing board or computer screen: it was a whole way of thinking about the world.”

Has there been a point when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward? It sounds like you’ve actually been pretty— Risk-averse. (laughing)

Yeah. The only real moment of truth that has changed my life more than anything else was when I decided to leave my job at Vignelli Associates after 10 years. I truly loved it, but I realized that I could see my whole future too clearly. I started there when I was 22. At 33, I thought, “Wow, that’s almost a third of my life on earth.” That was the moment when I sensed that I could either work there for the rest of my life or do something else.

Unfortunately, there weren’t a lot of other things I wanted to do at that point. I never had a desire to open my own office because it seemed too lonely. I also didn’t know anyone who would be a viable partner if I chose to start my own office. Plus I didn’t go into graphic design to come up with ideas by myself; I wanted to be stimulated by others. I simply wanted to be surrounded by people who I admired and be inspired by them. I was also a little on the old side, too: I owned a house and I had a second child on the way. All of that made me feel more cautious—and I’m already a cautious person—so the idea of going off on my own wasn’t appealing.

In the midst of that, I went out to dinner with one of my idols and mentors, a designer named Woody Pirtle. He had become a partner at Pentagram several years earlier, and he asked me if I’d be interested in joining. I asked, “As what? Your assistant?” He replied, “No, as a partner.” I thought about it and realized that their office model was perfect for me. At that point, I was looking for a greater degree of independence; at Pentagram, there’s no hierarchy and no one has a boss. Each partner works within the collective and gets support from the others, whether it’s logistical, such as office space, or emotional, or, if need be, financial.

Oddly, it took me a few days to work through the decision in my mind. Eventually, I realized that if I was ever going to get a new job, this was going to be it. Once I decided, I then had to endure the very painful experience of going in to break up with Massimo and Lella. I loved them, and I love them to this day. They never gave me any reason to quit. They were great bosses, but they were bosses, and they would always be bosses. Even if I became a full partner there, it would be like living with parents and having an apartment over the garage: no matter what, you’re still living with your mom and dad.

I basically wanted to go live in the commune that was Pentagram with these hippie friends I had met. (laughing) When I told Massimo and Lella, they were surprised and even a little mad because they hadn’t seen it coming. I was sad about that, but we all got over it and ended up as friends later on. Pentagram has been where I’ve spent my professional life since then.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself? Do people say no to that question?

Some people say their only responsibility is to their work, while some say they have a different sense of responsibility, but not necessarily toward others. In that case, I feel like I have a greater responsibility to the world in the context of graphic design. When you first start out as a designer, just doing the work is hard. In school, you’re critiqued about colors and shapes and typefaces in a completely foreign language that is so exotic and weird. Normal people aren’t acclimated to that, so your instructors attempt to give you a refined sense of form-making. At first, you think you’re learning to do something that is all about form-making. But if you’re lucky, you realize that it’s about form-making for a purpose. That purpose is communication.

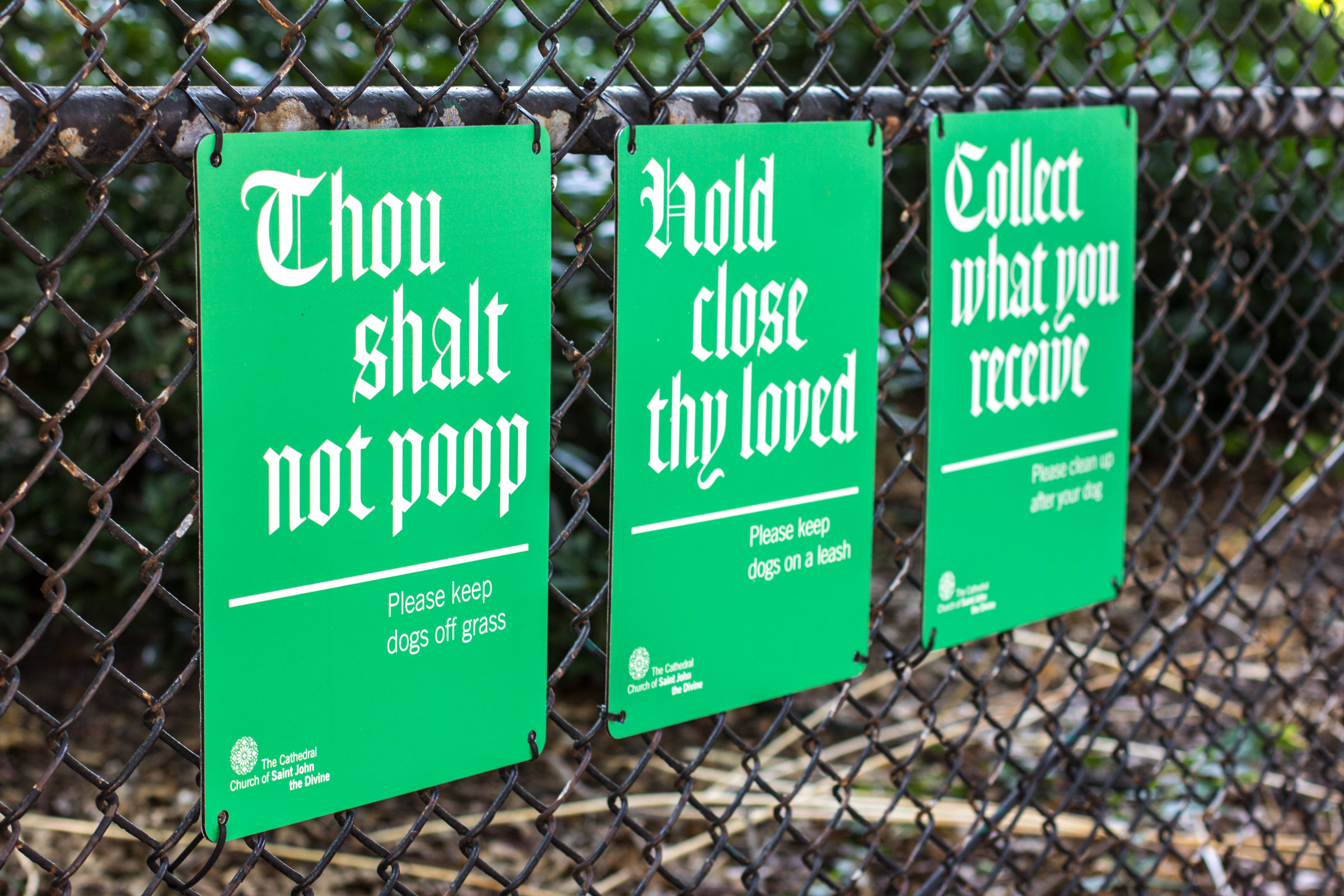

After school, you get a job. Suddenly your responsibility isn’t only doing work for yourself: it’s also about pleasing your boss. Then you have a responsibility to make a client happy. It’s easy to think that your greatest responsibilities are working for the aesthetic principles of form, working to make your boss happy, working to get approval from the client, and working to get paid. However, it’s important to constantly be aware that, as a graphic designer, you have chosen a profession in which you put communication out into the world. In effect, you are taking part in the public space that we all share, and you’re intruding on it. At the highest level of responsibility you do not intrude on the world with things that are untrue, crappy, dumb, or don’t deserve the space you’re devoting to them. And if you’re really doing it right, you avoid all of that and ask, “How can I do this in a way that will make people’s lives better?” That doesn’t mean only doing non-profit work. It means focusing on how you can take every single project—no matter the size, purpose, client, audience, or context—and and use it to make the world a slightly better place.

Now, not everything can make the world a slightly better place. But following your conscience to make something smart and good-looking, rather than dumb and ugly—depending on how you define those qualities—is a way to make the world slightly better. If you make a can of cat food look a little better, make the ingredients easier to read, or make the can easier to open or recycle, then designing that can of cat food is a social gesture that makes the world a better place. You can make a difference, even at the smallest level.

If anyone runs into a trap, it’s when they segregate those ideas in their mind. When people think they’re going to do this shit for the money and this stuff for their souls, it becomes a real disservice. They’re resigning themselves to be professionally schizophrenic: they’ve divided their minds in a way that, at its core, is somewhat dishonest. Those lucky people who are fully integrated at the highest level figure out how to make everything—their lives, their work, what they do for fun, and what they do for money—all the same thing.

I’m not at that point all day, every day, but my goal is to be as close to that as possible. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become less risk-averse about turning down projects that aren’t right for me, or walking away from work that I realize isn’t going the way everyone thinks it will go. I’m not a break-up kind of guy, though, so even when I have to tell a horrible client that it’s not working, I still say, “It’s not you. It’s me.” (laughing) I hate to hurt anyone’s feelings. If I’m lucky, maybe I’ll get more impatient and more prone to saying what I think as I get older.

Are you still teaching? Yes. I’m currently involved in the graphic design MFA program at Yale. I occasionally teach a workshop there, but I consider myself to be a pretty bad teacher. It takes stamina, the ability to pay attention to detail, and a belief in the infinite improvability of human nature to be a really good teacher. I know I don’t have that first ability, and I’m inadequate in the second. Every time I try to teach a long-form lesson, I get restless and bored. But the students become bored long before I do, so, in the end, we’re all bored. (laughing)

To combat that, I devise assignments that play to my strengths. I introduce a note of useful impatience or attention deficit disorder into an MFA program that is often based on the long, thoughtful, week-after-week analysis of problems. When I go in and give one-day assignments, I hope it’s refreshing for people to learn that you can sometimes spin around three times really fast, open your eyes, shoot an arrow, and hit the bullseye.

Are you still doing the 100-Day Project workshop with students? Yes, I am.

Tell me how that started. It actually came out of something tragic. I’ve lived in New York City since 1980, so I was here during the 9/11 attacks. Everyone was so shaken up, and I recall wanting to do something therapeutic for myself—something to get in touch with something that had atrophied a little bit. I decided to do a drawing in a notebook every day. To define the goal more, I decided to buy a copy of the New York Times every day, find a photograph in it, and make a drawing based on the photograph. If I felt like luxuriating in draftsmanship, I did a detailed, photo-realistic pencil drawing; other times, I summed up a photograph with gestural lines.

The drawings became a weird, visual diary of the things that were happening at that time. I started it on January 1, 2002, so it was still during the aftermath of the terrorist attacks. There was an anthrax scare, and snipers were driving around and shooting people at random in Washington, DC, and the Atlantic Coast area. I was surrounded by very disturbing news, and doing those drawings was a way to process it. I did the project for the whole year, making over 365 drawings.

“What’s great about the 100-Day Project is that you don’t need anyone’s help to do it. But if you want to undertake some kind of disciplined, sustained activity, then doing it in a group and feeling like you have the support of other people is incredibly useful.”

When did it become a project with your students? It became a project at Yale when Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, who is the head of the design department there, heard about it and said it might be an interesting project to give to students. At the time, I wasn’t sure what the project was—I couldn’t even explain it. (laughing) But then I recognized that it is a combination of forced, scheduled activity combined with complete, wide-open freedom. Outside of having to do the activity regularly, no one is going to tell you if what you do is good or bad, if you did it right or wrong, or that it has to lead to a specific result.

When I wrote the assignment for my students, it barely filled a single piece of paper. It said: “Starting on this date, pick a design activity that you can repeat every day for the next 100 days. On the 100th day, put it in a form that you can present to the class.” That was all there was to it. People asked, “What’s a design activity?” And I’d reply with, “What do you think it is?” Some people had very precise ideas, and some people had rather vague ideas.

It’s like running a marathon. Around day 15, people start thinking, “God, this is tedious and boring. Why am I doing this over and over again?” About three weeks into it, people come up with excuses for why they shouldn’t continue, but they press on. I checked in with students by sending emails about it once a week with a subject line like: “This is Day 32.” Sometimes I sent something inspirational, like accounts of creative people who set regiments for themselves or corollary examples, but I didn’t show up and demand to see what people were doing. On the last day, it was an incredible surprise. It was like planting a seed in a garden and seeing what had grown 100 days later. Sometimes people crashed and burned; other times, ideas that seemed preposterous or uninteresting in the beginning turned out to be amazing.

I have to admit that I started to get bored with it after a while, so I gave myself a break after the fifth year. I wrote about some of my favorite student projects over the past five years on Design Observer, the site I’ve worked on with Jessica Helfand, the late Bill Drenttel, and the British journalist Rick Poynor. After I wrote that post, other people started picking it up. Debbie Millman now gives it as an assignment in her program at the School of Visual Arts, and she does so much more thoughtfully and with much more rigor and attention to detail than I am capable of. I sometimes critique her students’ projects, and they do a great job.

What’s great about the 100-Day Project is that you don’t need anyone’s help to do it. But if you want to undertake some kind of disciplined, sustained activity, then doing it in a group and feeling like you have the support of other people is incredibly useful. That’s why I enjoy the idea of the 100-Day Project being a social project.

TGD alum, Elle Luna, documented her own 100-day project last summer, and she’s doing it again this year, beginning on April 6th. We saw your tweet stating that you’re going to participate—have you decided what you’re going to do? I haven’t picked what I’m going to do yet. I’m going to be traveling a lot during that period, so I would like to do something portable that won’t require me to set anything up. I would also like to do something that will permit me to engage with the places I’ll be traveling to so that I can make the most of the experience.

Awesome! So, what advice would you give to someone starting out? I try to remind people that being a graphic designer is fun. Sometimes people complain about have clients, but my advice is to use design as a secret disguise to infiltrate whatever world you want to go into. If you do that over and over again, and then translate that interest and curiosity into the work that you’re doing, you’ll do great. If you do it right, you can use the excuse of graphic design as a way to go places you’d never go otherwise, learn things you never would have learned, and find yourself in situations where you wouldn’t normally be.

The reason I love graphic design is because it’s a way to get paid to learn new things. For example, let’s say someone asks if you’d like to design a book. It’s not about being interested in pagination, covers, binding, typography, or paper. Those are all important, but what really makes designing a book fun is being interested in whatever the book is about. Sometimes it’s a great and exciting book that you’re really into: that’s like someone asking, “Would you like to sit and eat ice cream with me?” But sometimes it’s a book whose subject you don’t know about at all, so you get to talk to people who may be the world’s foremost experts on that subject. Even better!

When I brief interns about a project, I don’t say, “It’s this big and it has x amount of words and pictures.” I say, “These people are trying to do this, they’re trying to get this message across, and their big challenge is that.” Those pieces of information put the project into a larger context. That’s how I learned when I was starting out. I was a pretty good designer in college, and I’m not sure I’m a better craftsperson as I was then. However, I’m a much better designer now because I made people pay me to go from dumb to smart over and over and over again.

How does living in New York City influence your creativity or your work? I work in New York City, but I’ve lived in the suburbs since 1984. My wife and I moved there before we had kids, but it turned out to be a nice place to raise a family. It seems boring, but I actually love it. I once had the privilege of designing a book for Tibor Kalman. I remember that he wore boring, unstylish Brooks Brothers suits all the time. When I asked him about it, he said, paraphrasing Gustave Flaubert, “Dress like a bourgeois, think like a revolutionary.” The idea is that you should waste as little time as possible on being crazy in your outward appearance—the way you dress, the way you live, the way you behave—and instead use that energy to be as revolutionary as possible in your own mind. Maybe that’s the justification I use for this tame, dull life I live here in the suburbs: I’m revolutionary, even though I look boring. Although, I am sort of boring, so maybe I’m telling myself that to feel important?

What does a typical day look like for you? Oh, the guy who invented the 100-Day Project has very rigid ways. (laughing) I wake up really early in the morning, usually between 5am and 6am. I try to jog three miles every single morning—I ran this morning along the Hudson River when it was 14 degrees out. I go almost every morning, unless I have to be at work really early or it’s raining or snowing heavily or it’s below 10 degrees. I have a chart that goes back years, documenting every day I’ve run, with little notations by the dates. I start my day with that stupid ritual.

My three kids are away at college, so it’s my wife and I, and our West Highland Terrier. After I jog, I walk the dog. If he’s being good, he’ll do his business promptly. Then I take him home and leave for the train, which is only four minutes away. The train can take anywhere from 35 to 45 minutes to arrive at Grand Central Station, but I actually love the commute. There is something about the regularity and the time I have to think on the way into the city and back home. It’s very comforting to me. When I get to Grand Central, I go to the same Starbucks and buy the same coffee. Depending on how I want to mix it up, I might get on a Citi Bike and ride down to Pentagram or take the Fifth Avenue bus.

Once I’m at the office, anything can happen. My favorite kind of day is when I don’t have too many meetings. That lets me work with the designers on my team, have fun, and design things. It’s harder if I’m going from meeting to meeting or presentation to presentation. All of the partners at Pentagram are working designers, so none of us show up in the morning hoping to do administrative stuff all day.

If I’m lucky, one of my three kids will either call or text me. Two of them are in California, and my oldest daughter is a lawyer in Manhattan. I’m in contact with them as much as possible. It’s wonderful having three grown-up kids who are great people.

My wife works as a psychotherapist on the Upper West Side, so we’ll sometimes grab dinner together after work. Sometimes we drive home together and other times one of us will get home before the other does. Once we’re home, we talk about our days and then go to bed. The next morning, I wake up and do it all over again—and it’s great! It’s the same thing every day, and I love it.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave? I have two answers. The first is that, as someone who does creative work, I like the idea that there may be a couple of things I’ve done that will survive me. What’s great about being a graphic designer is that when people see your work, most of them don’t even know that someone does that for a living. My fantastic mother-in-law, whom I adore, went to Saks once and bought something that came in a bag that I designed. My wife tried to tell her, “Michael designed those bags, you know,” but my mother-in-law couldn’t figure out what that meant, exactly. A lot of the work we do as graphic designers is stuff that tons of people won’t know was made by anyone, but the idea that some of it will survive our lifetimes is exciting.

The second thing—the corny answer—is actually my real answer. If the three kids I mentioned earlier, Martha, Drew, and Elizabeth, go out and do anything good in the world, I’ll take the greatest satisfaction in that. In many ways, parenthood is the ultimate design challenge. Seeing each of my kids go from babies to adults with full personalities and watching them go through all of the great experiences and challenges that come with being a grown-up in the world today has been really exciting for me. I’m sure that’s a common answer to this question, but it’s the truth.

“In many ways, parenthood is the ultimate design challenge. Seeing each of my kids go from babies to adults with full personalities and watching them go through all of the great experiences and challenges that come with being a grown-up in the world today has been really exciting for me.”