- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker March 11, 2014

- Photo by Noah Kalina

Nicholas Felton

- designer

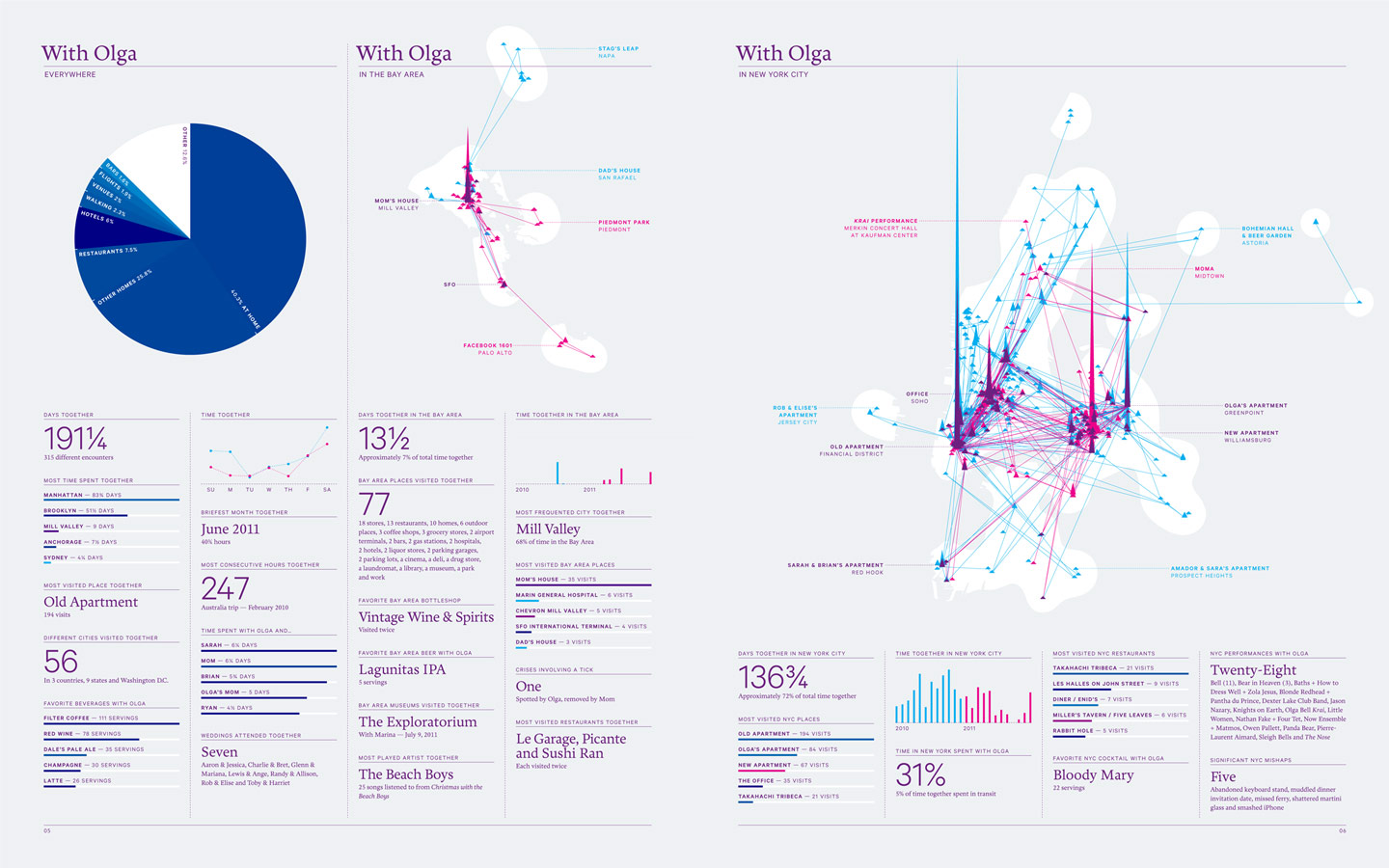

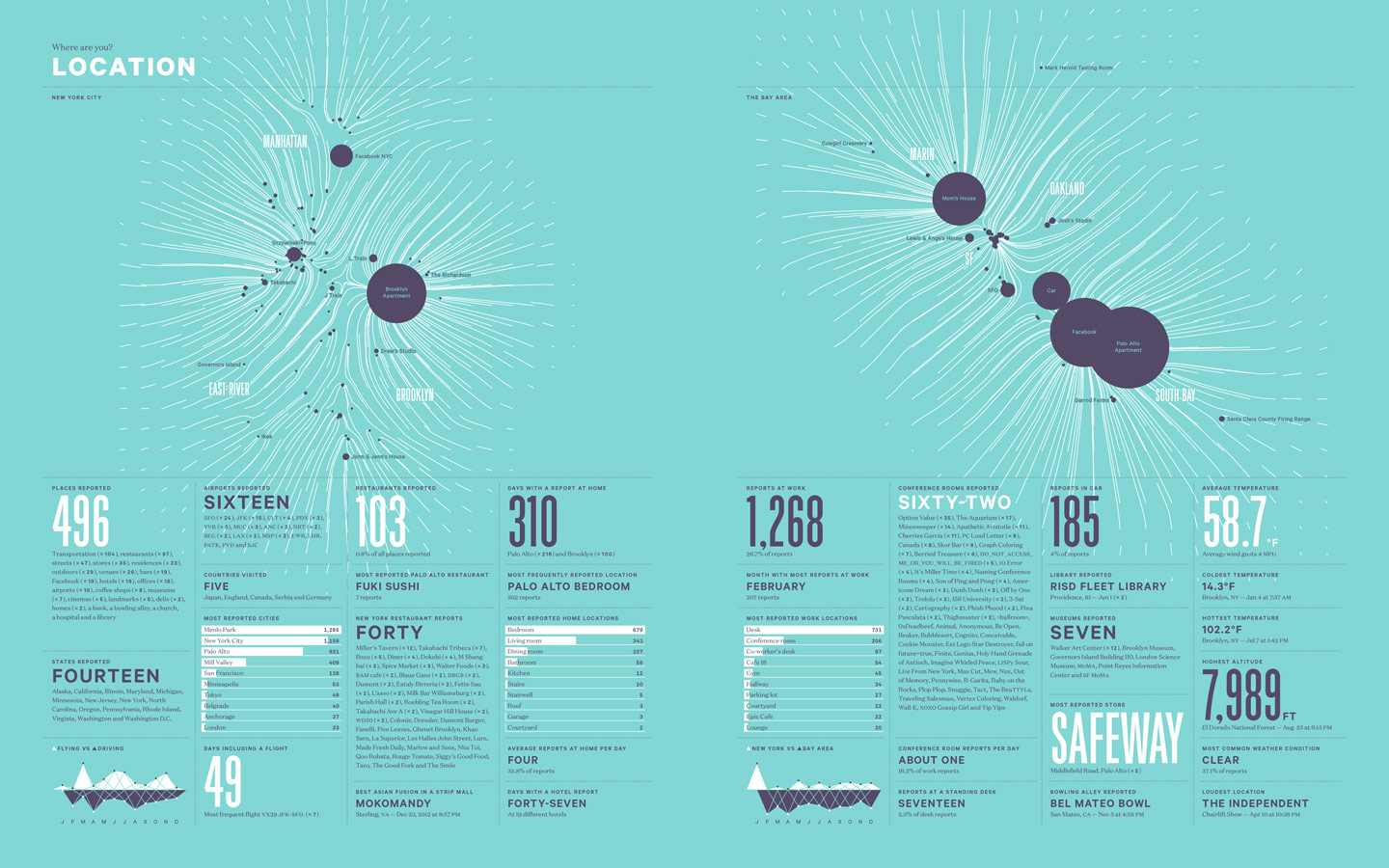

Nicholas Felton spends much of his time thinking about data, charts, and our daily routines. He is the author of several Personal Annual Reports and cofounder of Reporter and Daytum.com. Previously, he was a member of Facebook’s product design team. His work has been profiled in the Wall Street Journal, Wired, and Good Magazine, and he has been recognized as one of the 50 most influential designers in America by Fast Company.

Interview

Tell us what you’re you up to right now and the path you took to get there.

Right now is a little complicated. At this very moment, I’m working on Reporter, an iPhone app that was launched about three or four weeks ago and helps you gather personal data about yourself. I’m also working on another Annual Report, which is something I’ve been doing for nine years. I try to graphically encapsulate a year in this 16-page document, but it gets more and more convoluted each year—I’m hoping to have this one done by April. I’m also starting up on another iPhone app, so that spans what I’m working on right now.

Previously, I worked at Facebook for two years where I was one of the designers responsible for their Timeline. I got there at an interesting time when they were scrapping the old profile and wanted to totally reinvent it. Some of my experience working with aggregate histories came in handy there.

Prior to that, I had been doing a lot of independent data visualization work for magazines.

Around 2009, a good friend and I started a company called Daytum.com. We tried to encapsulate the idea of the Annual Reports into a website and iPhone app that people could use to pick a few things to count, like the number of coffees they consumed or the number of times they pet their cat. We approached it like a blogging service for data and, by default, there was no privacy. We wanted people to track stuff that they wanted to share, and we were intrigued by what people started to capture. There were the obvious things like people tracking media consumption, reading, and people counting up the items in their closets; then, there were people choosing to track non-obvious things. For instance, we had one or two dogs on the service—their owners were tracking their behavior—a couple people were tracking sex and drug use, and others were doing retroactive stuff like counting up concert tickets. Daytum is still limping along, but my attention has moved on to other projects.

If I take another step back, I was a generalist designer before I started the Annual Reports, which led me into the world of data visualization. Prior to that, I went to Rhode Island School of Design (RISD).

Tina: Let’s start in your childhood and move forward. Was creativity a part of your childhood, or was there any indication that you’d be doing what you’re doing now?

I think there were some signs. My dad was an engineer; my mom, who was a private chef and worked for The Beatles when she was younger, spent most of her time raising us kids, but also did plenty of creative things. She drew and sewed, decorated our lunch bags wonderfully, and helped us with school projects.

There is an accounting gene that is latent in myself and my sister—my sister is actually an accountant—but it’s not my strong suit. When I was younger, there was one book called Comparisons that I loved and consumed from cover to cover. It was a visual accounting of the world and was 200 pages of diagrams that illustrated things like the tallest waterfalls. It was a book I loved to death as a child and still go back to from time to time.

I always wanted to be around the creative kids at school. I didn’t excel at my arts courses, but I continued to take them and hang out with the kids who could draw far better than me. When the first Mac showed up in our house, I saw the creative potential there: I was able to start making some of the things that I didn’t actually have the competency with my hands to produce. I had a good friend named Josh who was a great illustrator and he and I came up with schemes for businesses and whatnot. In high school, he somehow wrangled the money to produce a comic book—not just a zine, but something that had national distribution and was sold in comic book stores around the country. I was just learning Photoshop and Illustrator at the time. For the comic book, Josh and two other friends did the story and illustrations and I became their graphic designer and production chap. We’d spent late nights working in Photoshop, cleaning things up; I also made the mechanicals and did coloring for the cover. It was a good opportunity and, somehow, I think it convinced RISD to accept me into their program.

Once I got to RISD, it was a natural fit. I found the medium of graphic design, which was aligned with what I wanted to do—that’s when I knew I was in the right place.

“…the Annual Report personal project has elevated my career enormously, but it was only one of many personal projects that I tried along the way—no one gave a hoot about most of them.”

Did you have an “aha” moment along the way when you knew that design was what you wanted to focus on?

I had a lot of internships when I was growing up, which I credit to my friend Josh. He always says it was me and I always say it was him, but we’d do things like stake out companies that we were interested in. For example, Industrial Light & Magic is just north of San Francisco in the county where I grew up. They didn’t have signs on the doors, but Josh found out where they were—I think he asked a postman. Then we sat in a deli across the street and a guy came in with a big jacket that had “ILM” on the back—they had these varsity jackets that looked amazing. We were 13 or 14, and we talked to the guy. He asked us if we wanted a tour and he took us in. It was like the scene from the end of Indiana Jones, filled with artifacts from Star Wars movies and the recently completed Hook. We did this all over the place. We got into Pixar when they were making Listerine commercials because that’s in the Bay Area as well. Josh ended up getting an internship at ILM and I had one at a video post-production house in San Francisco for a few summers.

I don’t know if there was a “this is it” moment until I got to school. Even when I applied to schools, it was a bit of a crapshoot. I think my mom believed that I could do it and that I wouldn’t be living on the streets with a graphic design education, but my dad was harder to convince. It took a year of me excelling in school—or maybe even graduating and getting a job that could pay the bills—before he decided that it was worthwhile.

Did you work for someone else after school?

I worked for a company called DiMassimo, which is an ad agency in New York. It was a pretty random connection; the owner of the company had met a friend of the family, who said, “You should meet this kid. He’s graduating from school.” I came to New York for a couple of interviews after graduation, and that one went really well. They offered me a job on the spot and asked me to start the following Monday.

Advertising was never something that was considered a career path at RISD—I think we were supposed to be starving artists. It turned out to be really great, though. It was an excellent foil to the education I received at RISD, which was about learning the fundamental craft and how to solve problems. In advertising, you work for people with a lot of money. How will you convince them that one approach is right for them when they could take any number of approaches to an ad? DiMassimo was one of the first agencies in the US doing brand planning with strategists. There was a group of people who researched the audience and would come back and say, Brand X, your strategy should be puppies with parachutes, or some core quality. If the client bought into that, then everything I designed had to have that touchstone at its core. I worked there for two years and it helped prepare me for having my own clients. It taught me how to speak and how to convince clients that my proposals were the right approach.

Did you go out on your own after those two years?

Yeah. I left there in June 2001 and worked on my own for the summer. Then 9/11 happened and it looked like the end of the economy, so I went back and worked for another larger ad agency for about six months before going back out on my own.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

There were definitely teachers at RISD who I loved and who supported the strange things I wanted to do. For example, for my final project, I decided that I wanted to make an exhibit that included artifacts from the book Catch–22; some were actual artifacts from the book and others I made up. This gave me the freedom to make model airplanes and design my own camouflage. Having teachers that supported that was great, even though once I got into the market and started showing it at portfolio reviews, people didn’t know what to make of it.

At DiMassimo, I first worked as an art director. I was designing ads, but got pretty fed up with that after a year. I put my foot down and said, “I’m a designer. I need to be doing identities and more of the fundamental graphic work rather than just applying copy to photos.” They went out and found me a design director, a great designer named Warren Elwin; a Kiwi who had worked throughout the ad world in New York. He and I and another friend, who came in to do architecture and 3D work, formed a design group at the agency. Because it was 2000, it was the first dot-com boom and there were all these clients coming to the agency who had the worst identities you could imagine, but they had funding and strategy. We churned out logos and identities and stationery suites for them, and it was a terrific time.

“The products that I’ve built thus far have not been about chasing the most profitable ideas. It’s been more about, there’s a vacuum in the world and this thing needs to exist—let’s build it. That’s always been the driving motivation for me to make or try things.”

Have you taken any risks to move forward?

I think so. Quitting my day job was probably the first one. There was a point at which I decided I only wanted to do data-driven projects, so I gave up on all the other miscellany that I had been taking on. Going to Facebook was an enormous risk, but one that my girlfriend supported by telling me to go to California and chase the opportunity. I think Facebook was the biggest risk, but also the biggest reward. Now, it’s fun to take smaller risks, like releasing Reporter, which I didn’t know if anyone would care about. Fortunately, it’s been received really well.

Tina: You just mentioned your girlfriend, who we happen to know. Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Yeah. I can’t think of anyone who has told me that I’m doing the wrong thing. I think that sometimes the things I want to do are a little bit ahead of what they expect or they’re just not familiar enough with the world in which I work to understand it. But everyone is supportive and always has been. They have faith in the decisions I make.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Absolutely. The products that I’ve built thus far have not been about chasing the most profitable ideas. It’s been more about, there’s a vacuum in the world and this thing needs to exist—let’s build it. That’s always been the driving motivation for me to make or try things. I want to do things that haven’t been done before, or make things that don’t exist, in order to fill a need.

Are you creatively satisfied?

I think so. I’m sometimes frustrated by my abilities or the amount of time I have to spend on things, but in terms of my output, I think I’m doing pretty well.

Is there anything you’d like to explore in the next 5 to 10 years?

Yeah. I’m working on it. I have a couple of further out projects that I think I’ll be ready to tackle in two to three years. The Annual Report project will probably only last 10 years, so I’ll do one this year and next year, and then I’ll put out a book and call it a thing. The environment around it has come full-circle in a way that ties it up nicely. In terms of what I’ve learned from it, there have been a couple different ideas I’ve had: Daytum encapsulated one of them; Reporter encapsulates another; and the next project I’m working on next should fill in that third slice of the pie. Getting that out and expressing that point of view about personal data and how to make sense of it will be rewarding.

After that, maybe I’m out of ideas. I don’t know. There’s always stuff to learn and every time I learn something new, it inspires me to make something else.

Tina: You probably can’t talk about your upcoming project?

(laughing) No, I can’t.

Tina: Is there a timeline for when we can expect to see it out in the world?

Yes. I’ve been working with a former Facebook engineer to prototype some stuff. There’s still a long way to go, but he’s coming out to New York next month and we’ll start hammering on it pretty quickly. The hope is to have something out in three to six months.

Tina: So our readers should be on the lookout this summer.

Yeah.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out?

The approach that served me really well was to make stuff all the time. Even when I was working full-time, I was always freelancing, doing work for others on the side, or working on personal projects. Certainly, the Annual Report personal project has elevated my career enormously, but it was only one of many personal projects that I tried along the way—no one gave a hoot about most of them. Not letting that discourage me, I kept trying other things. It wasn’t about finding “the idea,” but putting things out that I thought were worth doing and seeing if anyone cared. If not, I moved along. You learn as you go, and it gets easier or your point of view becomes more refined.

Tina: That’s good advice. If you try something and people don’t embrace it the way you hoped, then work on another idea.

I think that’s been encapsulated well in the make something every day or take a photo every day projects. People come out the other side of those feeling transformed. It’s hard and challenging, but it leaves you with a huge body of work.

You’re in Brooklyn. How does living there impact your creativity?

I don’t know. It’s funny. I was talking about this with a friend and my girlfriend over dinner the other night. So many of our friends are starting to creep away by moving Upstate and changing their relationships to the city. It made me reflect on what New York and Brooklyn mean to me. I live in Williamsburg and work near the Navy Yard, so there are days and weeks on end where my entire life happens between a few restaurants, work, and home. To some degree, it really doesn’t matter where I am, but other days I realize how amazing it is to have all the personal and public resources of New York at my fingertips.

You mentioned that you were here for some time and then you were in San Francisco. You recently moved back to New York. What was that transition like?

It was probably different than most because I grew up in Northern California, just outside of San Francisco. For me, going back there was a job. I lived in Palo Alto and, on the weekends, I’d go spend time with my mom or see high school friends or sometimes socialize with people I’d met at Facebook. In some respects, it was like an extended holiday or project. The first year was primarily spent in the offices, working 12 to 16-hour days and then relaxing in the hills of Marin and eating home-cooked food.

I also faked living in California somewhat by coming back here all the time. I did three weeks there and a week here. I think the biggest change was getting a car and having too many places that mail showed up. (laughing)

Tina: When you moved back here, you drove across the country, right?

Yeah. I got my first car when I went back to California. After leaving Facebook, I decided to keep the car and do what I’d always wanted to do: drive from California to New York. My girlfriend, Olga, and I figured out this convoluted itinerary that had us driving a lot, but got us through a bunch of national parks that we’d never been to; we saw the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, the Badlands, Zion National Park, and the Barringer Meteor Crater. I got her back to Minneapolis in time to fly to LA to do a show, and I drove the rest of the way by myself. It was amazing.

Tina: Nice! Any fun stories from the road or insights on, I don’t know, America?

(all laughing)

We went at this amazing time—the first week in May. There weren’t a lot of tourists yet and most places were unaffected. It was super quiet and we felt like we had a lot of parks to ourselves.

Also, Yelp was amazing for the trip—my girlfriend was incredible at finding the best places to eat in every city we went to. The challenge was getting there before 7pm so they weren’t closed. I think it was in Rapid City or Cedar Rapids that we had a molecular gastronomy meal that was delicious. We were shocked to learn that that had made it so far into the country, but being a locavore hadn’t. The restaurant was getting its beef from Texas and bragging about it, even though there was probably a cow 40 feet away. It was interesting to see how quickly culture can be transmitted, but still have a little bit of a gap from city to city.

Tina: Did you collect any data on your trip?

Last year was an ambitious year where I was trying to capture all of my communication, including conversations. That was hard on the trip because I did most of the driving. Once in a while, I’d have Olga write down a couple things before I forgot, especially when on those long, two-hour stretches.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Yes. I feel like I’m part of a few, but my favorite is the one I’m learning the most from right now. The world of artist coders, Processing, and Open Frameworks is this really vibrant community that is making interactive and data visualization things. I’m very much a newbie, but I find the people incredibly inspiring. Outside of the online community, there are a couple of great conferences: Resonate in Belgrade, which I’m going to next month, and Eyeo Festival in Minneapolis, which happens every year in June. I’ve spoken at both, which was amazing. I learn so much every time; I meet the people who make these languages and the primary practitioners who feed back into it because it’s all open source. Talking to them about what I’m struggling with or the ideas I’m considering is always incredibly valuable.

What does a typical day look like?

I have two flavors of days. At the moment, I’m in Annual Report mode. That means I get up, go straight to the office, eat lunch and dinner there, and come home at 11pm or midnight. It’s the only way to get this project done because it’s so much work—this year it took a month to clean up the data before I even started designing. It also commences this great feedback loop where I solve problems when I walk to lunch because I’m so involved in it or I can’t sleep at night because I’m thinking about how to do something in code or how to represent something. For me, that all-encompassing intensity is the only way to move the project forward.

That’s one mode. The other mode is more relaxed and involves exercising and having social outings. The weekends are pretty malleable, though. It’s nice that Olga and I don’t have day jobs, so if we want to do something midweek, we’re free to do that. Or, if we have a lot to do, we’ll work straight through the weekend. Sometimes it being the weekend means I work from home for a few hours rather than all day.

What music are you listening to right now?

A mix of the hits and some obscurities. I resisted Drake for a while, but I started listening to that album a few weeks ago. Also, my music consumption goes way up when I’m in the studio 12 or 14 hours a day. I try to find threads of interesting stuff on SoundCloud. I found Diplo’s stuff on there the other day and then started listening to his BBCR1XTRA stuff. That’s been keeping me going.

Favorite TV shows or movies?

My favorite TV show is River Monsters, an Animal Planet show about this Brit who goes around the world to different rivers where people have claimed to have a giant fish sighting. There’s really cheesy dramatization of people getting attacked, but I don’t know—I think it ties into my interests. I wanted to be a marine biologist for a while, and I really love the natural world and get a lot of inspiration from it. It’s a way to peer into the unknown.

For a long time, my favorite movie was Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, which is about World War II. Again, it had ties to nature. It scratched that boyish itch of watching a war movie, but it was also about the absurdity of fighting a war in paradise. I think I saw it at the same time that I was reading Catch–22 and the themes were similar. The cast and soundtrack are also amazing.

Do you have a favorite book?

The book that I enjoyed most recently usually takes that title. The Lost City of Z was an amazing book that I was giving to friends for a while. It’s about the search for El Dorado—again, in a rainforest. It was fascinating.

A really great one that I read a year or two ago was The Most Human Human. It’s central theme is the Turing test, which was Alan Turing’s challenge for artificial intelligence. Each year, the AI community meets and has a Turing contest for the most human-like computer, but there is also a contest for the most human human. It’s a study on what makes us human and how we can express it.

The book proposed this one idea of “getting out of book” that I loved. In the game of chess, there are a set number of ways it can open and close, but in the middle, there are infinite permutations of how the game can go. It’s the same with human conversation; the way we talk to each other starts one of several ways and ends one of three or four ways, but it’s what happens in the middle that is really magical. The more formal you are, the more you stay in book. You’re not doing anything original; you’re just playing out social constructs. It’s when you get to the middle and stop talking about the weather and actually learn about somebody that it gets interesting.

Tina: I really like that!

Ryan: Yeah, that’s good. Alright, what is your favorite food?

Probably Japanese food. I’m enjoying sushi while we still can.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

That’s a very difficult question. There’s a universe of personal data around us. The thing I’m trying to do with my work is connect people with the footprints or data they create. I’m hoping, in some way, to liberate this data. I think there is a massive inequality between information that services, companies, and governments have about people versus what individuals have access to. That needs to at least be made level, if not skewed in favor of the people who actually generate that data. I’m trying to lift the veil on the size, power, humanity, humor, and narrative potential of our data by making tools that allow people to leverage it. Legacy-wise, I hope that by making people more aware of data and its value, it will have consequences in terms of what services, companies, and governments do with it and how they share it.

“I’m trying to lift the veil on the size, power, humanity, humor, and narrative potential of our data by making tools that allow people to leverage it.”