- Interview by Ryan Essmaker October 3, 2017

- Photography by Ryan Essmaker

Dan Christofferson

- artist

- illustrator

Brooklyn-based artist/illustrator Dan Christofferson’s personal story is deeply rooted in the fantastic imagery, iconography, and narratives of Utah’s Mormon church & state. Here, he reflects on making the decision to move his family from his hometown, Salt Lake City, in order to carve out a new path in Brooklyn; on the mutually-beneficial nature of his partnership with Dan Cassaro at Young Jerks; and how his ideas around design legacy (and working late) shifted once he became a father.

Let’s start by talking about your backstory. I’m curious how you originally got into design, illustration, and art. I feel like I was one of those lucky kids who knew that I should be in some sort of art. My friends would get all dressed up as Ninja Turtles and jump around, and my inclination was to get out a piece of paper and a pencil and draw them. I noticed there were only three fingers on their turtle hands, (laughing) and I felt myself cataloguing things like that when I was really young. I don’t know why the Ninja Turtles were so important to me, but I remember thinking about them as a series. Each had its own name and color, but there was this one turtle design. I loved that, and noticed early on that it was kind of my thing; to catalog.

When I was in kindergarten there was this art contest called the Reflections Contest, and I drew this scene of a castle, a knight, a princess, and a dragon—it was all stick figures. But I remember when I was looking for colored paper to draw it on, I found an old yellowed one in a stack, and thought that would be cool because it was like an old parchment map. So I drew the scene on that. Those kinds of thoughts, like making a scene into a period-correct design or illustration, would pop up in my head. And I won! So I had these little boosts along the way that made me feel like I was doing the right thing. My parents were also super supportive, and got me into art classes where we’d go to the zoo and draw animals. And in high school, I went into an art program at the local college. It was just so natural; I never questioned it or tried anything else.

You were already thinking about systems, and little details, and the design aspect of things at such an early age. Yeah—I would draw things in a series. I don’t know what it is about illustration and design that makes you want to build a system, or to assign rules to things. But I was really interested in that, and also finding flexibility within those rules, and little ways to stand out.

I grew up in Utah in a religious family. In Utah, the history of the state aligns exactly with the history of the Mormon religion. You go to public school and learn about the state’s history, but also Utah’s religious history, which made it hard for me to understand the difference between my religion’s history and my family’s ancestral history. They tell you these really fantastic stories as truth—there are hundreds of them. There’s one about the early settlers in the valley who were trying to grow their first crops to survive through the first winter. Right as they’re about to harvest them, a swarm of locusts comes down and starts devouring the crops. The Mormons didn’t know what to do, so they all prayed around their crops, and then a flock of white seagulls swoops in and devours all of the locusts and saves the crops. That’s told as historical fact. And I grew up thinking all of that was real, so it made it easy for me to build stories in my own head and create these fantastic illustrative ideas that I could apply to art projects. Doing things in a series, like a set of icons that all work together, all ties back to that. You go into any religious building in Utah, and you’ll see that they’re telling this really complicated religious narrative through a series of illustrations.

“I started to realize that maybe I was more culturally Mormon than spiritually…I loved that that was my background. It gave me this treasure chest of cool symbols to pull from. It was all part of my life, but the belief wasn’t really there.”

Did you try to separate yourself from the church at a certain point? I did. I started to realize that maybe I was more culturally Mormon than spiritually. My ancestors are Danish immigrants who were converted and then came over. You see a lot of that in Utah—people who were born in Europe somewhere, and then came there and filled the state with culture. And I loved that that was my background. It gave me this treasure chest of cool symbols to pull from. It was all part of my life, but the belief wasn’t really there.

Was there a certain point when you felt like art was something you could make a career out of? I had an “Aha!” moment in art school. I was so unaware of the commercial side of art—I just assumed that you studied painting and drawing, even though so much of my influence came from illustrations on skateboard decks, t-shirts, graffiti, and magazines. That stuff was all around me and it influenced me heavily. But I never understood that someone paid an artist to do those, and that that artist in turn used that money to buy his lunch and coffee. (laughing) I just never connected those things.

I was in the art program at the local college and I was studying painting and drawing in a really traditional 2-D sense. One day, I was standing next to this guy in my painting class and we were painting still lifes, and I remember him asking me where I wanted to teach when I was finished with my degree. He said it in a way that suggested that we all just go back and teach art at some school—like there’s nothing beyond that. I remember thinking that the scope of that felt really scary to me. It was heavy. I didn’t want to go back and follow the same path to my old high school to teach, and then maybe teach at a college one day.

Across the hall, there was this computer lab where the design and illustration majors worked, and I remember all of them sitting at these computers doing really cool graphic shit. I was starting to use some of that stuff in my paintings; I would design a piece and print it out and add it to some layer of my painting. And I was spending more and more time over there, and had this “Aha!” moment where I realized there was another path I could take. The careers they were looking at were in designing typefaces and applying their illustration skills for commercial client work. So I switched to a visual communications degree with an emphasis on illustration, which is when I began to understand the commercial viability of what I was doing. I could see a clear path, and understood how I could use all of this stuff. I still did a BFA—I made oil paintings with graphic vector illustrations mixed in, and rounded it all out with a graphic brand around my BFA installation. I think it was helpful to have gone through that, to have learned to render and draw all while I was learning a graphic design sensibility.

“…I switched to a visual communications degree with an emphasis on illustration, which is when I began to understand the commercial viability of what I was doing. I could see a clear path…”

When you graduated, did you start doing your own stuff, or did you take odd jobs or work in a studio? I worked at a t-shirt shop right before I graduated—a really bad one. I remember redrawing artwork that was given to the shop. Like they’d want the Dixie Chicks, but they couldn’t be the exact Dixie Chicks, so I’d have to draw caricatures of them, and alter them subtly. I had no idea who they were. (laughing) I was pouring myself into things like trying to do the best almost-Dixie-Chicks drawing I’d ever done. I had all of this creative energy, but nowhere to put it. That didn’t last very long.

Then I jumped right into a not-so-glamorous design job right out of school. I got hired on at a credit card company doing really basic design—all of the annoying marketing materials credit card companies use, like fliers you get in the mail to try to talk you into signing up for an account. Looking back, it was great because I was able to gain experience while experimenting, and often failing on projects with low or no expectations. I learned a lot and tried a lot of different things. It gave me enough experience and variety to then find a job at an agency doing work that I could be proud of. One of the main clients at that agency in Salt Lake was a candy company. So some of my fondest memories are of doing candy packaging: illustrating taffy and chocolate; studying how interesting dielines worked together, and for their packaging; touring the candy factory and sticking my head into the chocolate fountain. (laughing)

Where did the Beeteeth moniker come from? I was doing personal work on the side while I was at that agency. Some of it was freelance client work, but more and more of it was me trying to find that fine art voice again and I needed something that represented that. There’s a lot of narrative behind Beeteeth, and weird arcane symbolism. Utah is the beehive state, and their state symbol is the beehive. So I looked to Utah’s story of the hardworking Mormons who came there and worked together like a little hive of bees to grow this beautiful city in the middle of the desert. I don’t really know where the “teeth” came from. I just liked the double “e” in bee and teeth. It all fit at the time. And no one ever knew how to spell my last name, Christofferson, when I was growing up. So when I was thinking of a website, like christofferson.com, I felt like it didn’t have enough character and I’d inevitably run into problems. So I just stuck with Beeteeth.

I want to shift to something more recent. What led to you joining forces with Dan Cassaro and making the move to New York? There’s this thing in Salt Lake, and I think maybe in a lot of Midwestern cities as well, where the sentiment is like, Creative people: quit going to the coasts—stay and build something here! And I felt that really intensely. Especially being connected to Salt Lake through my family’s history. There’s this really powerful, rebellious undercurrent there—an underground subculture and passionate, straight-edge culture—because there’s a lot to fight against. The government is really conservative. So I felt this strong desire to stay and lend whatever I could to Salt Lake. I left that agency after a few years, and then worked for Big Cartel for six. I was really invested, and I felt like I kind of found myself there. But I always had this feeling that I couldn’t just grow up and live in one city. I had to travel a little bit, and experience the vibe of a new city. My wife and I had also had a kid, and we were growing out of our apartment—all of these things were coming together at the same time.

How did you meet Dan? I had met him a few years before at a creative conference. I did that thing maybe for the first time in my adult life, where I e-mailed him and said, “Hey, you want to be buddies?” (laughing) And he was like, “Yeah, sure man!” So we hung out and we got along really well, and then we started doing projects together. It was this great back-and-forth, where the exact things I was lacking in my work, he was amazing at. And the things that maybe he couldn’t dial as quickly, I was great at. I was in charge of illustration, and he was in charge of lettering and typography.

While I was at Big Cartel, I hired him to do a mural in Salt Lake City. One day, we were painting together and talking, and I told him that I was feeling this itch to move on from what I was doing; to try something new and maybe do my own thing. And he was at a point with his design studio where he was turning down work that he didn’t want to turn down, and was also really enjoying working with someone he could bounce ideas off of. So he just casually posed the idea of partnering up. He said it so confidently and easily that I was like, “Yeah, OK!” I went home and asked my wife, “You want to do this thing? You want to move to New York?” She was into the idea, so we did it. We moved out here, and crashed in his basement for a month while we found an apartment. It was exactly what I needed at the time. We’ve been here for two years now.

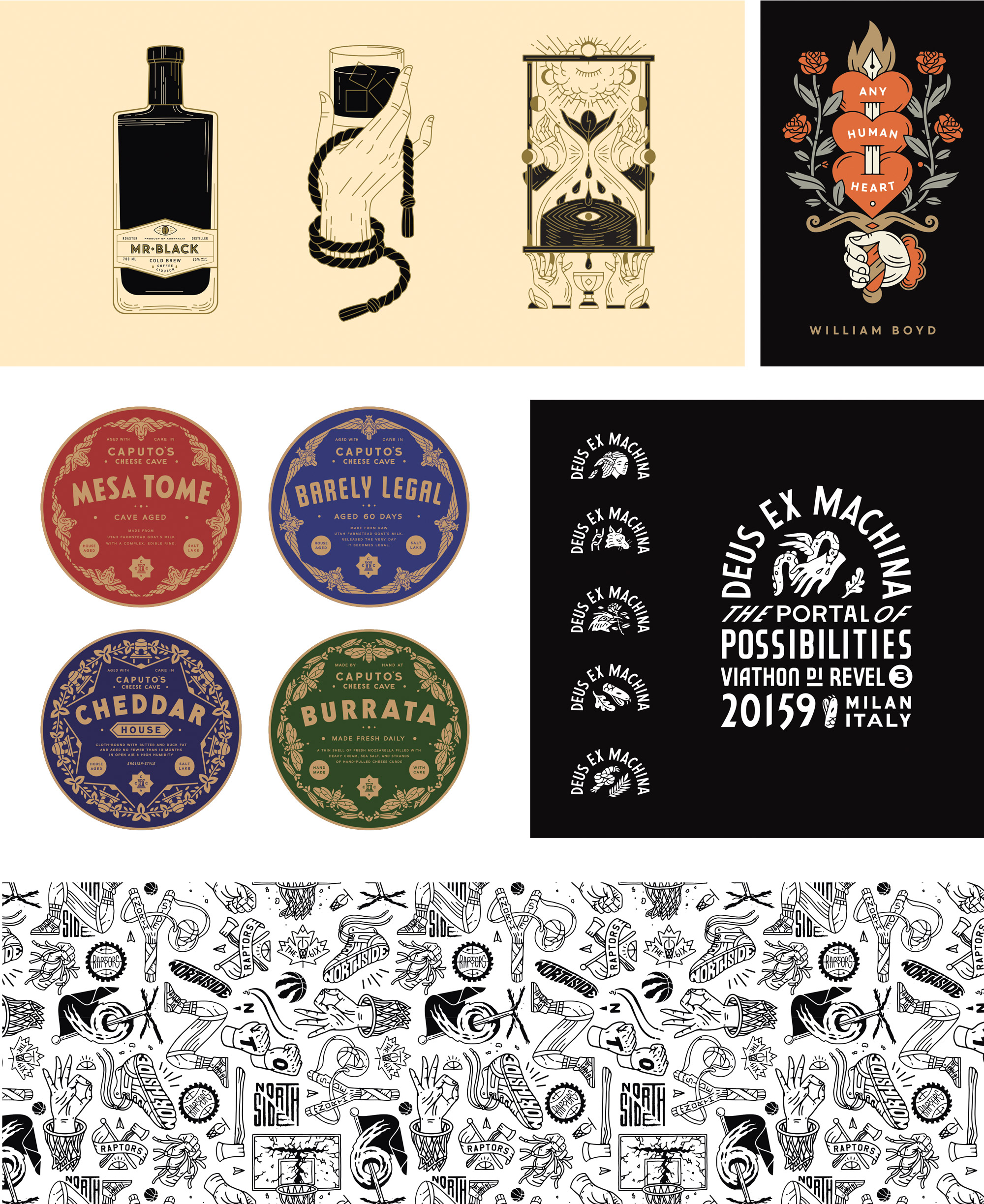

Dan and I still find ourselves thriving in those roles. I’ll put together some design comps, and the illustration aspect of it is really fleshed out and the typography is just sort of scribbled in, (laughing) and I’ll pass it to him and ask, “Will something fit in right here?” And he’ll be like, “I got it, I got it.” And he’ll do the same thing where he’ll refine a bunch of typography and lettering and then put a weird horse guy here or something, and pass it back to me. It’s so cool for both of us. It makes my work better, and makes us both more efficient.

“There’s this thing in Salt Lake, and I think maybe in a lot of Midwestern cities as well, where the sentiment is like, Creative people: quit going to the coasts—stay and build something here! And I felt that really intensely.”

Now “Young Jerks,” plural, makes sense. Yeah! (laughing) It made an honest man out of me. Dan was always Young Jerks, but there was no other “jerk.” It just made sense.

Earlier you talked about feeling torn between the urge to stay and build community in Salt Lake City, and going out on your own and moving to New York to do something else. Has being here had an impact on your creativity? And do you still feel that same pull toward Salt Lake? The density of creative people here creates and encourages opportunities. There’s an ecosystem that supports design and illustration, and the close proximity to clients encourages that. I picked up on all of that really quickly after moving here. I’m in a studio with all of these people doing all of this brilliant work, and all I have to do to get a unique perspective on something is lean back at my desk to peek over the shoulders of world-class designers and illustrators.

There are incredibly talented people in Utah, of the same caliber, I think, but less density. The same ingredients and recipe are there in the smaller cities, but there’s just something about the density, and maybe more importantly the diversity, in a city like New York that amplifies all of that inspiration and gives you access to so much more. I still feel a little bit of guilt about leaving Salt Lake, and I have this idea to go back again when I’m older to set something up and work from there. I haven’t quite planned that out yet. But that’s maybe what I tell myself to feel better about leaving. (laughing)

So, are you creatively satisfied? Yeah, I am. I’m really satisfied. When I moved here, I had to answer to a partner on a lot of the creative decisions I was making, and I realized that I hadn’t been challenging myself. I wasn’t as good of a designer as I wanted to be or had thought I was. In my Salt Lake bubble, I saw myself in a different way, and then I came here and I realized I needed to become a better designer. There was this weight on my shoulders, and a lot of pressure—having moved to a city like New York that’s very hard to get started in, and I also had a new kid. I remember feeling really stressed. I had anxiety for the first time in my life, and I actually didn’t know what it was. I thought I had some kind of lung sickness. I was like, Man! I feel this weird pressure in my chest when I breathe, and I think maybe I have pneumonia or something. (laughing)

All of that new pressure was really good for me—I’ve become a much better designer, and I’m more confident. And because of that, I’m more creatively satisfied. But I think, for me, creative satisfaction has always come from the act of just taking a moment to get all of the images out of my head. Even with a quick sketch—it opens up the roadblocks, which allows things to move more freely.

Has the anxiety subsided? It has. I figured out these two things: read a book on the subway, and drink coffee! It was a really rewarding thing to allow myself to read on the train. So I became a reader, and I also started drinking coffee to harness whatever that anxious energy was. I’ve also just learned to manage it a little better.

What advice would you give someone who’s just getting started? You ask someone about inspiration, and they’ll usually say I look at everything around me and let it roll around, and then I use it. But it’s another thing to find a tangible system to be able to do that. It started really simply for me—when I was in high school, I had an art teacher who I really connected with. She encouraged me to build a system in my head, where I was cataloguing the world around me and everything that would benefit my art.

So I started thinking about how I could take everything around me and organize it in my head in a way that I could use it. I decided to take her advice very literally, and I studied everyone’s noses for a day. As I walked around school, I’d just look at everyone’s nose. And then I’d look at tear ducts, and then eyes. I did that on and off for a few years, where every day I would focus on a specific thing. It was a way of giving myself a little assignment. As an illustrator that’s helped me to be able to exaggerate face shapes really well, and to form this system of cataloguing that I could regurgitate into something authentic and useful. So the advice I would give is to be inspired and influenced by everything that’s around you, but then to build a cool system to be able to use all of that.

“When I moved [to New York], I had to answer to a partner on a lot of the creative decisions I was making, and I realized that I hadn’t been challenging myself. I wasn’t as good of a designer as I wanted to be or had thought I was.”

I like the idea of being hyper-focused on one thing every day. I see it all the time, where letterers will draw a page of just capital A’s or catchwords or something like that. It feels like such an easy solution, giving yourself one thing to focus on in a world that’s flooded with imagery. It can really help you slow down to come up with something fresh.

Do you think about your own legacy? What other people thought about me was a big deal before I had a kid. It drove me to do things like working late to come up with a few extra sketches for a client. I’ve sort of let that go now, and maybe even the idea of a legacy of great design work. I saw my desire to stay up late to work on a project get replaced with thoughts about the developmental milestones of my kid, and how I could be involved in those and help shape his personality. That was a really satisfying shift for me—it made me realize that the lasting legacy would be the impact that I made on another person. If he grows up to be kind and supportive, I think that’s much cooler.

It sounds like your life has a little more balance now. Do you think having a child has made an impact on the passion you have for your work? Maybe not my passion, but it’s definitely affected the amount of time I dedicate to it. It’s so much easier for me to unhook at the end of the day now. My wife is creative as well, so before we had a kid, we would come home from our day jobs and make dinner and then sit right back down to our desks and work on projects until we fell asleep. It was rewarding, but I think it kept me on one track. Having a kid has helped me think on a deeper level about the development of another human. When your kids are young, you look at your partner at the end of each day and think This kid is still alive! That puts things into perspective. I helped keep my kid alive, versus drawing another skull with a rose. (laughing)

“…for me, creative satisfaction has always come from the act of just taking a moment to get all of the images out of my head. Even with a quick sketch—it opens up the roadblocks, which allows things to move more freely.”