- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker December 3, 2013

- Photo by Catalina Kulczar

Baratunde Thurston

- comedian

- entrepreneur

- writer

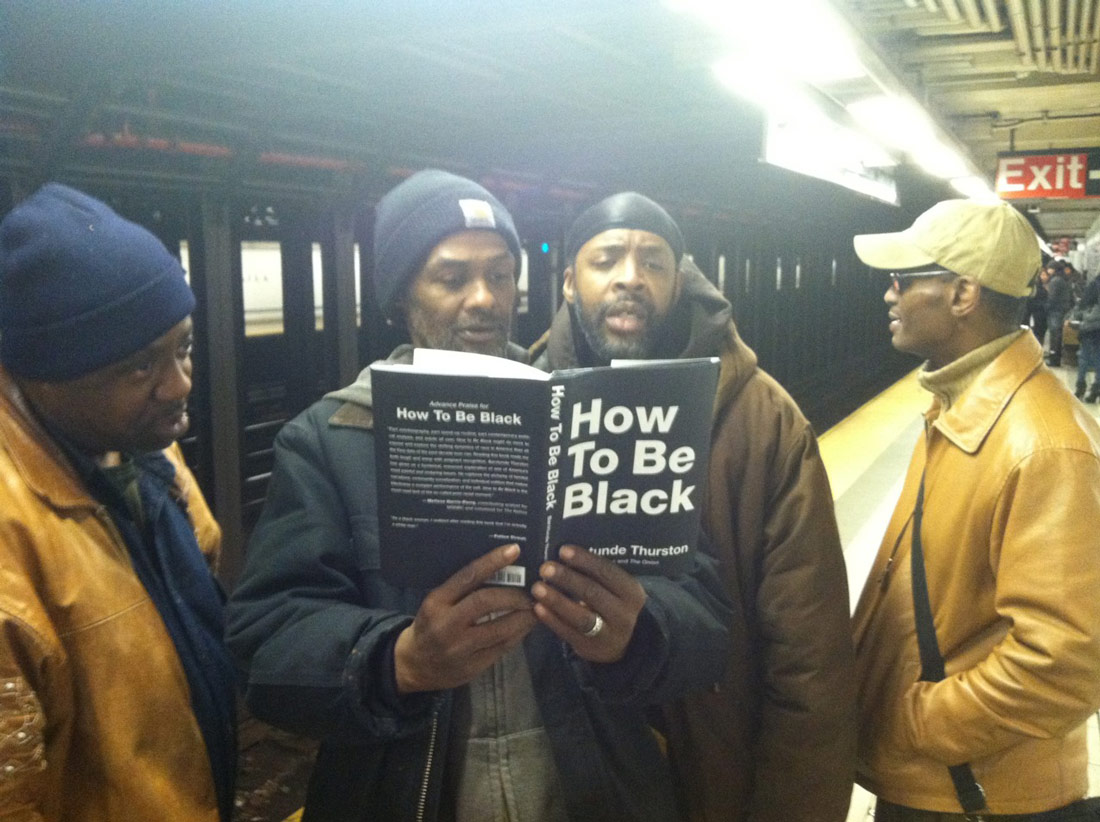

Baratunde Thurston is the CEO, cofounder, and hashtagger-in-chief of Cultivated Wit. He is author of the New York Times bestseller, How To Be Black and previously served as director of digital for The Onion for five years. Baratunde cofounded the black political blog, Jack and Jill Politics, has advised the Obama White House, and has over a decade of experience in stand-up comedy. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Interview

Describe the path to what you’re doing now.

(Joyously singing and clapping) Birth canal! Birth canal! I came out of a birth canal! That was literally my path. Next question.

(all laughing)

Wait, how will you transcribe the singing and clapping?

Tina: Tammi, our intern, is going to have to figure that out. (laughing)

Good luck, intern!

(all laughing)

Tina: So what are you doing now, other than making us laugh?

In some ways, that’s it, but through various means.

Right now I’m the cofounder and CEO of a company called Cultivated Wit. There are three of us at its helm, and we combine the power of comedy and technology to explain complex ideas; tell stories in unique ways; and humanize technology by deepening its relationship to humor and creativity. Sometimes we act as an agency by doing marketing campaigns with wit and digital pizzazz, but we tell our own stories more directly. We also do original productions, like the show Funded on AOL. Occasionally we’ll put on events—hackathons—where developers and comedians build weird and funny apps over a weekend. We have other ideas for products that we could launch out of that sphere, but that’s our base.

Outside of projects with Cultivated Wit, I’m a comedian, public speaker, writer, and pontificator. I wrote a book called How to Be Black, which I continue to support by doing talks on race, identity, politics, diversity, activism, media, and the new versions of all of them.

Tina: By the way, I like the piece that Cultivated Wit did about Detroit Soup. They’re doing great things.

Yes, they are. Thank you.

So, what’s the rest of your story?

I think my life is best explained by the lives that came before mine. My great-grandfather was born into slavery in Virginia in 1870—a year when that should have been legally impossible, but things are sometimes inefficient in America. He moved to Washington, DC, and the big family lore is that he taught himself how to read. He had two daughters, one of which was my mother’s mother, Lorraine Martin. She was the first black employee at the US Supreme Court building, and there was even press about her. However, I didn’t know any of that until 2005, after my mother passed away. My family never talked about it: we were quite broken and dysfunctional when it came to my mother’s relationship with her mother. By the way, most families are dysfunctional—if a family looks happy, then their secrets are usually even darker.

My mother, Arnita Thurston, was born in 1940 in Washington, DC, and grew up during the transition to Black Power. She was raised in a very Christian household—Baptist, with a white Jesus on the wall—which she left to become a black activist, civil rights street protestor, and radio station takeover specialist. (laughing)

That’s where my path begins. I was born in 1977, and I have an older sister, Belinda, who is nine years ahead of me. We were raised in a house with a very politically active and independent mother, and a father who wasn’t around. Our fathers never lived with us. My father was killed during a drug deal when I was six years old. He was the user, but no one knows exactly what happened. No one was ever caught, and there were no arrest records—just a death certificate and a body.

My mother never graduated college, but she was smart as hell and worked her ass off to get us a house to live in. She distributed Yellow Pages and sold dinners that we never got to eat to other families; she was a domestic worker who cleaned floors; she did paralegal stuff and secretary work. Eventually, she got herself a good job in computer science and became a programmer. She did that without any formal education, in the late 1970s, as a single black woman living in Washington, DC.

Tina: That’s pretty astounding.

Yeah. She just kept applying herself, studying, and busting her ass. Because of her, I grew up in a house full of fun contradictions rather than stereotypes. We lived in a mostly black and Latino neighborhood, and we were the only house that had a computer—an Apple IIe.

Tina: I remember that one. (laughing)

Oh yeah, I would play One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird.

Tina: I was into Oregon Trail myself.

I played that, too.

My mother had forged her own identity and path, and she wanted that for me, too. Growing up in the 1980s was an especially dangerous period, and it wasn’t a good time to be out on the streets of DC. My mom over-populated my schedule with stuff, in part to keep me safe, but also to expose me to the world.

The first chunk of my childhood was full of adventure: camping, swimming lessons, bike-riding, youth orchestra, Boy Scouts—my mom just kind of farmed me out. Because my dad wasn’t around, she substituted with extracurriculars, which were led by positive male figures. I remember two Latino guys named Pepe and Pinky who ran a bike shop; then there was a photographer named James, who played the cello and bass, worked as a bicycle courier, and owned several massive fish tanks with all sorts of fish—he was like five dudes in one. When I look back on it, I can see that I had an early dosage of possibility from the relative lack of limits my mother set up around me.

When I was in the seventh grade, there was a phase when DC got more dangerous. We saw drug deals outside the window and our mayor, Marion Barry, smoking crack on television—we had the original Rob Ford. My mother switched me from public school to Sidwell Friends School, which was part of the private school system. It was a very awkward adjustment: there was money, power, political kids, and white people everywhere. Growing up in DC, I didn’t see that many white people, and now I was surrounded by them. (laughing) I also had to step up my game academically. I had been in “Gifted and Talented” programs in public school and an after-school enrichment program called Higher Achievement, but they didn’t push me enough, so I was always running out of shit to do and getting into trouble because I was bored.

I exercised a lot of who I would become while I was at Sidwell. I became very political on campus about issues of justice, particularly racism. I also found out that I loved writing. Before high school, I had been all about math and science, but a friend of mine said I should try out for the school newspaper, and I loved it. I discovered girls, too—they didn’t discover me, but I discovered them. (laughing) I was great with adults, though. The first time I was put on panels was when I spoke for Sidwell at independent school conferences. I became a student representative, so I spoke to boards of parents, helped organize protests, and had meetings with the headmaster. High school was where I started speaking up and out, and that’s a big part of what I do now.

I also discovered the Internet in high school. At home and in the library, I used bulletin board systems, which connected through dial-up. Parents of a Sidwell student worked at one of the Internet backbone companies, and they donated a full-time high-speed connection to the school. I was present when they installed it over the summer, and I was one of the first people at the school to have an email address. I was already connected to tech because I loved Legos and all kinds of gadgetry, but there’s an endlessness to the Internet that a little kit doesn’t have. Discovering the Internet changed everything.

My first real act of subversion was through the Internet. A friend of mine had been expelled, and we all thought that the way it went down was unfair. The committee that did the convictions was stacked: the same administrator who had found it was also on the judging committee. We all thought, “You’re putting the police in with the jury, the judge, and the executioner?” Nobody was executed, but it felt that way because our friend had been at the school since kindergarten and was so close to graduating.

When my friend sued the school, I decided to do something. I had access to the deposition transcripts because I knew how to find court records online. I distributed the records selectively. Then I made dramatic black-and-white wanted posters with mugshots of the principal and dean of students along with a list of their alleged crimes. Did I mention I was a very self-righteous and dramatic person? Because I worked at the Washington Post at the time, I had access to massive photocopiers, so I was able to print out big “wanted” posters on broadsheets. I wanted to effect a dialogue, so I went to school early and plastered the walls with the posters. All the students had to go to a weekly “Meeting for Worship” in the gym, which is kind of like chapel, except nobody talks at you. Quakers believe there is “that of God” in everyone, and no priest or preacher is required. Instead, at Meeting, attendees occasionally feel moved to share thoughts, but it’s not required and is very informal. I had also covered the gym with the posters, and the meeting essentially became a rally—it was really nefarious shit. That was one of the most fun moments I’ve had.

High school is when everything starts to flower: acne, love, aggression, boldness, and confidence. (laughing) For me, a political voice started to flower. I had tipped off the newspaper about the case because I wanted to get the word out. I didn’t want credit and I didn’t want blame: I just wanted the truth as I saw it to be more visible. I didn’t want the information traced back to my email, so I hacked into the mail server at Yale and spoofed it to think I was another server. I’m not really sure why I chose Yale. I eventually ended up attending Harvard, so maybe future me saw it as poetic justice? The fake account I created was called [email protected]. I basically saw myself as a digital Deep Throat.

Tina: Did you get in trouble?

No one knew I had done it. I kept my mouth shut.

And now it doesn’t matter, right? (laughing)

Yeah, what are they going to do now—un-graduate me? (laughing) I’ve now admitted it to the school, though. I went back one year for a Mother’s Day show and talked about my mom’s influence, saying, “She would have been really proud of me for that.” The teachers weren’t exactly excited about that story, but the students loved it. Also, I—and probably my lawyer—feel the need to say for the record that, of course, I don’t encourage students anywhere to access secured computer systems for any reason. That’s against the law, people.

Tina: Did the friend who was expelled know what you did for him?

I don’t think so. Trust no one—that’s the first lesson. (laughing) People always get busted by bragging. I was able to keep it a secret for two years, until I was a freshman in college.

Where did you go to college?

I ended up getting accepted to Harvard early, despite my wishes to avoid your kind. (laughing) I wanted to go to Morehouse in Atlanta and be surrounded by my kind, as I saw it at the time. (laughing) College was actually when I started being funny.

Tina: You weren’t funny before?

I wasn’t funny growing up, but my family enjoyed humor. We took family road trips and listened to audio cassettes of Bill Cosby, Whoopi Goldberg, and Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon. I wasn’t a killjoy—I was fun to be around—but I didn’t make jokes or see myself as a kid who made people laugh.

Some of the funny was born in high school, when I found humor through the Internet and spread it around through email lists, becoming a curator of jokes. Before college, though, I was a serious, self-righteous, holier-than-thou individual. I wasn’t condescending, but I was very judgmental. I remember hanging out with some of my black friends after school and they were talking about how much they loved the Redskins. I said, “You can’t celebrate the Redskins—that’s fucking racist!” I wrote an op-ed in the newspaper about it because I thought it was hypocritical: people would hate a team called the Washington N-words, yet they were flaunting another derogatory term around? I demanded justice, but, obviously, nobody listened. Once I got to college, things got a little more refined. I was a member of the black organizations, but not in the same way I had been in high school. I was involved, but I didn’t feel the need to wear that label quite so loudly anymore.

I ended up starting a satirical newsletter at Harvard called NewsPhlash because I had always been obsessed with the news. I had worked at the Washington Post, taken a summer journalism class at American University, and written for my high school paper, but it wasn’t enough: I wanted to write news that people would actually read. (laughing) NewsPhlash was like The Onion, and was made up of concentric circles that covered campus news, local news, national, and international news. I still had a column in the school paper, but NewsPhlash became my creative home. It was a big part of college, and helped form the path that led me where I am today.

I was writing so much that I eventually got repetitive strain injury and couldn’t type. I couldn’t take my exams normally and had to use comically bad dictation software. (laughing) I had lined up a summer job to be a reporter in the business section at the Washington Post, but I had to bail on it because I couldn’t type. I ended up staying in Cambridge and doing theater instead.

Did you know what you wanted to do when you were younger?

The idea of what my path would be has changed over time. When I was in elementary school, I thought I’d be a preacher. It wasn’t necessarily about having a relationship with God: I’m a fan, but some of the literal interpretations don’t really work for me. I was mostly drawn to it because I liked public speaking and being on stage, and the idea of having a resonant connection with an audience and communicating something of a higher purpose to them was instinctual for me, even at an early age.

I was always a smorgasbord kid, though: I loved playing bass in my youth orchestra; I loved hacking away on the Internet at night; I loved writing for the school newspaper and advocating for justice—or what I saw as justice. But once I got into high school, things started to shift towards writing. Journalism emerged as a possible path, but I thought I’d do something in technology because I was so into math and science. College was when I started to think about my future differently. I thought about being a teacher so I could channel wisdom of some sort. I also thought about getting involved in a tech startup, since those were beginning to be a thing in 1999.

Everything I’m doing now is a version of something I did in college or high school. Writing for the newspaper was a precursor to my stand-up, and sitting on panels for Harvard relates to my public speaking. Being on the newspaper staff gave me credibility to speak on certain topics, so I was asked to represent my view, and occasionally the university’s view, on certain issues. I was a member of the Harvard Computer Society, I taught computer literacy in low-income areas, and I edited a book about the history of computing at Harvard. College was where I learned how to mix editorial content with technology, and use comedy as a tool for communication. Nothing has changed—I just get paid a little more now. (laughing)

What did you do after college?

Things just kind of played out once I graduated. I continued living in Boston and got a job doing strategy consulting work that gave me some business knowledge. I made spreadsheets, put together PowerPoint presentations, and gave corporate pitches to CEOs. It wasn’t my passion, but it helped my mind stay active and gave me another language to speak. Because of that, I feel very comfortable in boardrooms now. I’m still not the best chief of finance, but I can talk business without bullshitting. I know about markets, customer acquisition, and all kinds of stuff that isn’t typical for a comedian to know or care about.

I worked as a consultant as a sort of cheat: I was able to pay down my student loans and learn about business at the same time. I wanted to work for myself eventually, but I didn’t know what that meant, so my rationale was that I’d get paid to learn what entrepreneurship was from existing businesses. I did consulting for a year, and it was great. Then I quit to try to start a venture capital company, which was so foolish. The year was 2000, and I was about 22 years old. I chose business partners who were fresh out of college. (laughing) It was stupid, and I’d do it all over again! When that failed, I went back to consulting.

“…there were defining moments where I found the overlap of what I cared about and what I was good at. Finding that overlap is a beautiful thing, and it doesn’t happen for everybody. For some people, it never happens; some people find it really late; and some people find it when they’re four years old.”

Were there any “aha” moments when you realized what you wanted to do?

There is a continuum to my path, but there were defining moments where I found the overlap of what I cared about and what I was good at. Finding that overlap is a beautiful thing, and it doesn’t happen for everybody. For some people, it never happens; some people find it really late; and some people find it when they’re four years old.

In December 2001, I got a major path adjustment and affirmation from my then-girlfriend. She was a musician who was busking in the streets in Harvard Square, like Tracy Chapman. She was younger than me by three years, but she was already pulling off her creative dream. During a phone call, she innocently asked me: “Do you prefer to write or perform?” I answered honestly, saying, “Well, I like both. I enjoy the energy of performing and the precision of writing.” Then she asked, “Then why aren’t you doing either of those things?” I thought to myself, “Oh, shit!” (laughing) That was the moment when I thought, “I might end up marrying this woman.” She called it like it was, and it was in my best interest.

I had abandoned my creative self for consulting, eating sushi with my coworkers, slaving over Excel, and taking cabs home. There are a lot of perks to jobs like that, but those perks are chains as well; I had lost sight of that. My logic was that I needed to make money to pay off my loans and pay my mother back for school: I couldn’t afford to pursue and indulge in my art until I was financially independent. My girlfriend did not agree with that. She said I would either never come back to my creative life, and instead get caught up in the money game of never having enough; or I would come back years later without having done anything. Would I still be funny? What would I have to show for a decade of happenings? My potential loss of relevance terrified me. That night, I resurrected my NewsPhlash newsletter in blog form and started writing every Sunday.

Then, in the beginning of 2002, I began doing stand-up comedy. I commuted to DUMBO, Brooklyn, every Tuesday night for a three-hour comedy writing workshop. Over the course of six weeks, the instructors brought in some great guests for the class: the then editor-and-chief of The Onion; the producer from Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update”; Michael Schur, who went on to help write and create The Office and Parks and Recreation; Patrick Borelli the stand-up comedian; and Andy Borowitz from “The Borowitz Report.” It was awesome. We’d have an hour with the guest, then we’d workshop with each other and the instructors. The class let out at 10pm, but there were no trains back to Boston at that hour, so I would go to the Virgin Megastore in Times Square—may it rest in peace—for a few hours: it was bright, loud, and I could get a lot of work done. At 3am, I’d catch a train back to Boston, sleep using a little neck pillow, and once I arrived in Boston at 7:15am, I’d shower at the gym across the street from my office and go into work. That’s when I realized that this was my calling.

What did you do then?

I was at the consulting job by day, but my heart was not in it: it was just the means to an end. I was going to pay off my loans and subsidize my creative career. I started doing some political blogging in 2004; in 2006, I helped form Jack and Jill Politics. I started using my humor and politics to get plugged into the liberal blogosphere crowd, and they started to see me as one of their own: an activist with a comedic voice, but not as harsh as the pure policy voice. I thought, “These are my people!” I began emceeing conferences and getting calls from NPR to comment on things. I got called to be on CNN because we were one of the prominent blog voices on the Obama campaign. The producers told me, “Just say what you said on your blog, but with your face, into a camera. (laughing)” I had been training for that my whole life! I had essentially been media training since high school without quite realizing it, and everything started to make sense.

Another big “aha” moment was when I realized that I needed to leave Boston. Back in 2001, my mom had gotten sick—in fact, on 9/11, I was on a commuter rail from Boston to a town called Attleboro to visit my mom. She had just had surgery to remove a tumor from her colon, and my sister and I were taking care of her. She eventually recovered and opted out of chemotherapy because she felt great.

In the summer of 2005, I had been nominated for the Bill Hicks Spirit Award For Thought Provoking Comedy as a part of the New York Underground Comedy Festival. My mother had relocated to Portland, OR, and I wanted to visit her before I went to New York. When I saw her, she looked terrible: she was gaunt, sickly, and weak. The cancer had made a very aggressive return—it was late stage. I didn’t go to the comedy festival in New York, but the organizers said, “Don’t worry about it: take care of your family and we’ll honor your nomination next year.” My sister and I intervened as best we could and camped out at hospitals in Portland, seeing specialists and calling in every favor from everyone we knew—which was a good amount because, when you graduate from Harvard, you know some good people. One of my roommates had a connection with the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, so we had my mom flown there as soon as we could. Unfortunately, it was too late. She passed away at the hospital; she was 65 years old.

“My mother’s death was a catastrophic event in my life…That experience ended up affecting my humor. My comedy had never been about me; I had always been more externally focused, saying things like, ‘The world is fucked up, and here’s why! George W. Bush, blah, blah, blah’…but that changed after my mother’s death.”

Tina: That’s so sad. How did you react?

My mother’s death was a catastrophic event in my life. It sucked emotionally, which derailed me for a while. I couldn’t sleep, I was sick, and I felt sad and despondent. I checked out for many months before I made my way back. That experience ended up affecting my humor. My comedy had never been about me; I had always been more externally focused, saying things like, “The world is fucked up, and here’s why! George W. Bush, blah, blah, blah.” It was never very personal, but that changed after my mother’s death.

Things started to happen in the fall of 2006. I came back to New York City for the comedy festival I had missed the year before and spent two weeks here. That’s when I thought, “I need to live here.” I ran into an executive at Comedy Central, and she asked if I had moved to New York yet. I thought, “Yet? Does Comedy Central want me to move here?” I spoke with my comedy mentor in Boston and he told me that I was ready. I moved to New York City in the summer of 2007, and comedy was becoming more important to me, although it wasn’t paying much. I was still consulting to pay the bills, and I was supporting my fiancée—I had proposed to my girlfriend in December 2006.

Within a week or two of arriving in New York, I heard about a job at The Onion. I wasn’t necessarily looking for a job. I was still a consultant and wanted to use that income to subsidize my comedy, but the opening at the The Onion was perfect: they wanted a political editor. I thought, “Wait, I’ve been training for this my whole life!” (laughing) I got the job, but it came with a 50% pay cut compared to what I made consulting part-time. It was a terrible financial decision—especially since I was now paying rent in New York City—but it was the right life decision. I had a great run at The Onion: I was a web editor, in charge of politics, and became the director of digital strategy and apps. It was the first job where I could be techie, political, and funny. I was already in the minor percentile of people who have dreams and live them—but I was getting paid, too. (laughing)

At that point, I felt like things had stabilized. It was the summer of 2009, and everything was gravy: I had just started filming a TV show for the Science Channel about the future of science and tech, I was speaking at a lot of conferences, and The Onion loved me. Everything was riding high until my wife wanted a divorce. It came with no warning: we weren’t fighting, cheating, beating, or emotionally abusing each other. Getting divorced was just as traumatic, if not more so, than my mother’s death. At least my mother’s death came with some warning: she had been sick four years prior and there was always a potential risk when she opted out of chemo. Logically, parents are supposed to die before their kids, so it wasn’t unnatural—it was sad, but not unnatural. But my wife wanting a divorce was some unnatural shit. (laughing) That was a high-low week: I started shooting a TV show, and my marriage fell apart three days later.

Tina: Wow, that must have been really tough.

It was really fucked up, but it was a part of my path. She was going through things that she needed to deal with that had nothing to do with me. We’re cool, but I was definitely scarred; I think we both were. She didn’t love doing it: it was a very radical act that she took no pleasure in. On the positive side, my divorce left me with a lot of space and extra time, and it became a very creative period for me.

A really big moment came after I moved to Brooklyn and was asked to give a talk at the Web 2.0 conference. I wondered if I would be able do it, which was strange for me: I had never lacked confidence on stage, but I was emotionally distraught at the time, so I didn’t feel like myself. I ended up giving a talk about Twitter and hashtags, and the audience fucking loved it—the preacher in me was still alive and well. One of the 1,500 people who saw my talk worked for HarperCollins Publishers, and called me for a meeting. They made me an offer to write a book, and that’s how How to Be Black was born. There’s a longer version of the story, but I’ve been talking a lot, so I’ll leave it at that.

Tina: That’s awesome! Have you had any mentors or influential people in your life along the way?

There are a lot of influential people who haven’t done shit for me: Kanye is really influential, but he hasn’t done a damn thing for me. (laughing)

There have been a lot of people who have had a positive influence on me, but my mother is number one on the list. In my early childhood, the bicycle dudes, Pepe and Pinky, were like uncles that I never had. They taught me how to ride a bike and looked out for me in the neighborhood.

Another big influence on me was the five-men-in-one-man, James West. I looked up to him because he was cool, he hustled, and he made things work. Seeing a hyper-employed person who was creative, resourceful, and talented in so many different ways made me subconsciously want to aspire to that. He was a renaissance man, and given the range of crap that I do now, it makes sense that one of the people who had an early influence on me did a wide range of seemingly non-related things.

The principal of the middle school at Sidwell, Bob Williams, was another great mentor for me. My mother enrolled me in a Pan-African rite-of-passage program there, which she found out about from Bob. He was an elder in the community, and he was the reason my mother was cool with me attending school at Sidwell. She thought, “This guy is looking out for my son; he’s one of us.” Beyond being the principal of my middle school, Bob was like a father figure: he had a lot of clout, respectability, and wisdom. He looked out for me, which was really great to have early on.

My English teacher at Sidwell, Erika Berry, was the one who suggested that I take philosophy in college. It wasn’t on my radar, but I ended up majoring in it. Philosophy restructured my brain in terms of how I interpret the world, how I ask questions, and dissect arguments. Reading philosophy can help build up an aptitude for seeing through bullshit—or at least seeing through some deeper layers.

Ryan to Tina: It’s interesting that philosophy keeps coming up in our interviews.

Tina: We’ve interviewed several people who have majored in philosophy and then gone on to do a lot of different things. When they tell us that they majored in philosophy, it makes sense because they’re always really critical thinkers.

It’s a great point of view to have, and it gives you a lot of tools. Some people with philosophy degrees go into law because analytical thinking applies there.

Another mentor-like figure is my older sister. She always looked out for me when we were growing up, and she has painted a really healthy path forward in life. After she quit journalism, she started a donation-based yoga studio in Lansing, MI. It’s a for-profit, community-based studio that brings yoga to people who can really use it, most of whom are people that yoga is not marketed to. Most of yoga is Lululemon, Yoga Journal, $30 class fees, $50 smoothies, and $60 pants. This doesn’t have any of that bullshit—my sister is providing another point of relief and community for herself and a bunch of other people. I really admire her; she’s one of the best people I know.

“There’s really no excuse to not be better, because we have the tools…if we don’t take advantage of that, it’s because we’re choosing not to act. I don’t want to be a part of that. Willfully avoiding betterness is shitty.”

Tina: Have there been any points in your life when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward?

Yeah, I jumped out of a plane once. That’s always a big risk.

Tina: Skydiving?

Yes, for the Science Channel show. (laughing) They didn’t film it because they refused to cover the insurance, so I just did it on my own, and I have the video to prove it! That was part of the summer of 2009: getting divorced, filming a TV show, signing a book deal, and jumping out of a plane. (laughing)

Getting married was a risk. It’s a big risk to entrust your life and completely intertwine it with someone else’s, and, clearly, it doesn’t always work out. I don’t have any regrets and I’d do it all over again. We had a great time while we were together, and she was very important to me, professionally and personally.

Moving to New York was another big risk. Holding on to the consulting job lowered the risk a little bit, but I didn’t have anything to do here; I just wanted to live here. People say things like, “You’re so brave! I can’t believe you did that!” I never thought taking comedy writing classes, commuting to New York, and doing open mics were really risks: they were opportunities. I have a degree from such an amazing university that I’ll probably be okay if it doesn’t work out. The worst-case scenario is that I get a job somebody envies. Ok, it’s not a worst case scenario, but the point is, I recognize the fortune of my circumstance, so I don’t really see any of that as a risk.

Financially speaking, cutting the cord to my consulting job to work at The Onion was a big risk. That job wasn’t guaranteed to work out, but it did. For about five years, I had a pretty awesome experience. Well, the last year wasn’t entirely awesome as the company planned its move to Chicago, and many of us figured out if and how to continue with or without the company. Again, that’s a separate and much longer story, but in the end, a majority of the creative staff opted to leave in the second half of 2012. Some pursued independent projects; some joined the late night writing staff; a bloc ended up at Adult Swim; and a small contingent went with me to create Cultivated Wit.

Starting Cultivated Wit in the wake of all of that was another big risk. Businesses fail: that’s what they do. I could have just taken a job and ridden the solo artist train as a writer and performer. I would have been fine doing that, but I really wanted to build an institution with people and try to have a bigger impact. Doing something like that with a team is much more effective than just being a personality.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I want to contribute to something less than me. I want to totally fucking dominate it and yell, “I’m bigger than this!” I want to take an inconsequential outcome and just focus on that. (laughing)

But seriously, I do feel a sense of responsibility to contribute to something bigger. I was born to a ridiculous generation of people who took real risks. They went out into the streets, got beaten, went to war, or fought against those things. I have a lot of respect for that. We have different challenges now, and maybe some of those are more difficult, but in the grand scheme of things, we have it easy. Knowing about all of the people who died of natural and unnatural causes and led to my presence here makes me feel an obligation to try and honor them. I was raised with a little too much respect for history to forget that.

Certainly not every action I take is honoring my ancestors. (laughing) I’m not drinking this beer on behalf of dead slaves. Not everything is grandiose in that sense, but we have a bit of an obligation because of our opportunity to do things better. There’s really no excuse to not be better, because we have the tools. We literally have footage of history that we can look back on to recognize the times we fucked up. We have data from social sciences and neuroscience now that explains why bad shit happens. There are a lot of things we have access to, so if we don’t take advantage of that, it’s because we’re choosing not to act. I don’t want to be a part of that. Willfully avoiding betterness is shitty.

Are you creatively satisfied?

No, but that’s not a negative no: it’s just an incomplete yes. I am very proud of most of the work I’ve done, although some of it has been really shitty.

I’ve had the fortune of creating in many different media. I feel like my canvas and brushes are quite diverse, but there’s so much more that I want to do. The frustration and lack of satisfaction is due to time. In some cases, I already know what I want to do. In other cases, I know that what I want to do will emerge over time, and as the tools emerge, I’ll want to pick them up and play with them. However, there are some things I want to do, but I can’t yet because I’m not competent enough with my brush, or keyboard, or language. There is stuff I want to do with technology that I can’t realize, and it’s very frustrating. I see it, but I can’t create it, yet.

I’ve even thought about taking a couple months off so I can disappear and take up something new. There are things within my grasp that I have yet to execute, and there are things just out of my grasp. I covered a Nirvana song with a live band a couple months ago, and it was so much fun! I like singing, but I haven’t done shit with that. I love dancing, too. There’s a one-person show that I’ve been squatting on for 10 years that I haven’t done anything with. It’s frustrating to be surrounded by possibilities, but know that I can’t do everything. I live in so many different worlds, so I see a lot of different things, and I get hungry for them. I see how they can be applied to each other, and I want to be the person—sometimes the first person—to do them. I am satisfied creatively with what I have done, but I am nowhere near finished, and I doubt I’ll ever be. I am regularly frustrated by my lack of resources, especially time. It’s not about money: it’s about having the time to keep pushing. Also, money helps.

“I am satisfied creatively with what I have done, but I am nowhere near finished, and I doubt I’ll ever be. I am regularly frustrated by my lack of resources, especially time. It’s not about money: it’s about having the time to keep pushing. Also, money helps. ”

What advice would you give to a person who is starting out?

If you’re just starting out, try a lot of things; and if you’re going to try five things, make sure one of them is something you never thought you’d be interested in. Exposure has been the biggest lesson in my life. Not everything pans out into a job, a gig, money, accolades, or respect, but there’s usually something worth learning, even in the pursuit of something you don’t like. The greatest lever in my life has been exposure to variety. In the world that we have created for ourselves, nothing is stable; nothing stands still. You can’t just know a thing, master it, and then rest on your ass. You could be great at something today that won’t exist tomorrow. Look at print journalism or the cable TV model: things are crumbling around us, and new things are emerging. There’s a level of flexibility that should be built into whatever it is that you’re doing, and constant exposure to things that are new, different, occasionally distasteful, or not obviously interesting is important.

One year, I wrote an interactive guide to SXSW. A lot of people usually go to events like that for work, and not many people try something new outside of their field. People who do mobile marketing always want to go to every session on mobile marketing; if you’re a designer, you want to read the latest on design. No! Go to the weird thing: go to the quantum physics thing; go to the augmented reality thing; go to the puppet theater thing, and just throw yourself out of your comfort zone. You don’t have to go against your morals or anything—just try some random shit.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

I don’t quite live anywhere, but New York City is home. I don’t have an apartment because I’m traveling so much.

So you’re a “gentleman hobo,” a term that our friend Cameron Koczon coined for himself last summer?

I like that. I’m going to borrow that for when people ask me if I’m homeless. I’ll reply, “No, I’m residentially flexible: I’m a gentleman hobo.” (laughing)

New York City is my home, and Fort Greene is still kind of my spiritual home. I also have a deep love for a certain pocket of Prospect Heights; I’ve stayed there for about three months over the past year. I’ve also grown fond of the East Village, and honestly, I’m now officially tired of the nomadic life. I’m currently looking for a real, stable, honest-to-goodness apartment to rent. No roommates! But, I’m just saying, if anybody knows of anything…

The thing I like about New York, especially Brooklyn, is the hustle and affirmative competition. The competition is usually constructive instead of destructive, so it motivates you to keep working because people around you are all working. I don’t work out of a fear that somebody’s going to take my shit; I don’t operate from that place. I work because I want to be great. There’s a lot of greatness in this city, and people flock here. It’s very motivating.

Since becoming a residentially flexible gentleman hobo in August 2012, I have found attachment, community, and love everywhere. I feel at home in many places, so I’ve had to force myself to declare New York City home. It doesn’t matter if I go to San Francisco, LA, DC, Detroit, or Boston: if there are good people, then it can be home. The city is very important, but it’s not everything. It’s the community that matters.

I love leaving the country. I love walking around other places, because it adds to my exposure and affects my creativity by giving me different inputs: different foods, languages, and transit systems. I travel so much that I lost myself in New York City once! I was walking on 44th street, and I lost my sense of place. I kept walking, thinking, “It’ll come back to me. I’m in New York, and I’m headed to—Rudy’s! Yes, I’m going to Rudy’s on 9th Avenue for liberal drinking at an event—okay, got it!” (laughing)

There’s obviously a problem with detachment there, but I think the ability to create a home—to find comfort and love in any environment—is really helpful. It has forced me to see positive things, to be resourceful, and to find beauty wherever I’m at. I used to think that I loved Brooklyn the most, but then I had a great experience in Manhattan and thought, “I just love New York! New York is the best!” Then I had a great experience in San Francisco, so then I thought, “Coastal cities are so innovative! Coastal cities are the best!” Then I was over in fucking Goa, India, and I thought, “Places with—uh—water in the air! Those are the best!” (laughing) I’ve realized that it’s the people who are important, no matter where you are. When people are the best, they are the best; and when they’re the worst, they are the absolute worst; but I have had far more encounters with the best. That affects my creativity, which comes from a place of positivity: there is often criticism in it, but it’s not nihilistic or destructive criticism. It comes from a place of joy, because I see it in so many different contexts, and that’s beautiful.

“In the world that we have created for ourselves, nothing is stable; nothing stands still. You can’t just know a thing, master it, and then rest on your ass. You could be great at something today that won’t exist tomorrow…There’s a level of flexibility that should be built into whatever it is that you’re doing…”

What does a typical day look like for you?

There’s not really such a thing, but I’ll try. I wake up to an alarm or two and brush my teeth and take care of bathroom activities. I then pretend to engage in this rigorous daily level-setting ritual involving meditation, yoga, and assessing my day. But at least half the time, I’m running behind, so I work in some stretching on the subway or breathing exercises on my bike ride into town, while I think peaceful thoughts as I bob and weave across the bridge that separates me from my duly appointed tasks for the day.

If I’m in New York—and let’s just say for the sake of a typical day, that I am—then I hit up Mudspot for a coffee while I scan through some Twitter headlines. Then I go to my East Village office, make a grand entrance sure to disturb my officemates, and plug into The Matrix behind the 27-inch screen of my iMac, submerging my ears beneath a set of air-traffic-control-looking headphones. Then: Gmail, Gcal, Asana, Google Docs, Hangouts, Skype call, conference call, Asana, drink some water, Gmail, Gmail, Gmail—basically I’m a professional emailer—then lunch break!

Lunch is almost always a meeting, followed by some plotting on a Cultivated Wit project or prepping for a public speech. Then it’s another meeting, more high fives at the office, and then on the bike to some sort of evening affair, perhaps a fundraiser or show or media meetup type thing. Maybe there’s food at that evening thing; maybe not. Somehow I find the calories and then head back to the office for some quiet work time after the Internet and my inbox have settled down. I jam for another hour or three, then hop on the bike or subway or maybe take an UberX back to wherever I call home. Did I mention I’m looking to rent an apartment like a grownup again?

(all laughing)

Do you have a current album on repeat or any music that you’re into right now?

Yeah. I bounce between Rdio and Spotify, so folks can get a taste for what’s going on by my profiles there. Lately I’ve been cranking Kendrick Lamar, the soundtracks for the six seasons of the UK television series, Skins, Alt-J, and Kanye’s Yeezus.

What are your favorite movies or TV shows?

Oh, man. That’s a loooong list, but I’ll try for rapidity. Best show ever: The Wire. Second best show ever: Breaking Bad. I’m tracking several shows right now: Scandal, Bob’s Burgers, South Park, The Walking Dead, Sons of Anarchy—which deals amazingly well with race—and I keep coming back to this intense UK series called Black Mirror, which is like The Twilight Zone dealing with mildly futuristic scenarios in which technology has severely perverse or negative social consequences.

Movies: Visually, Casshern and The Fall are the most beautiful movies I’ve ever seen. The Rock was the first DVD I ever bought, and I stand by that purchase. The Matrix is real, and Terminator is a documentary that hasn’t yet happened. Best Picture of 2013, hands down, without a doubt: Fruitvale Station. There are also other good movies I’ve enjoyed that have been made during my lifetime, but I’m going to stop talking now.

Do you have any favorite books?

Ahhh!! More lists of things I like. Yes. Here goes.

The following epic series: The Dark Tower by Stephen King, Ender’s Game series by Orson Scott Card, the Dune saga by Frank Herbert, and Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series.

The latest books that have rocked my world: Writing My Wrongs by Shaka Senghor. He’s a Detroit native who served 19 years in prison for murder, got his life together, and is now part of the solution rather than the problem. This book is his memoir, and it’s amazing. I consider it a first-person complement to The New Jim Crow.

Also the book Americanah. Just so good.

I love the writings of Joe Hill and Warren Ellis. They are both quite twisted and funny and twisted. So twisted.

Also, here’s a list of books I recommended to the attendees at TED in the Spring of 2012. They’re all great.

What is your favorite food?

The good kind.

One last question: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Let it be said about the man Baratunde Thurston that he loved more than he fought; that he stood more than he sat; and that he listened more than he talked! (laughing)

Honestly, I’d love people to think that I was generous, and that I had some kind of unique ability to make the unpalatable palatable. I want people to think that I was a translator and connector who brought people closer to people or ideas they might not have been connected to. I want people to think that I was fucking hilarious, a great dancer, and a great lover. (laughing) I’d love to have part of my legacy be that I was compassionate; that I exuded joy, warmth, confidence, and competence; and that I was more than talk—I was a man of substance.

“I’d love to have part of my legacy be that I was compassionate; that I exuded joy, warmth, confidence, and competence; and that I was more than talk—I was a man of substance.”