- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker July 16, 2013

- Photo by Ryan Carver

Jeffrey Veen

- designer

- entrepreneur

- developer

Jeffrey Veen is the Vice President of Products for Adobe, where he runs product development for Creative Cloud. He joined Adobe in October 2011 when they acquired Typekit, a company he cofounded and ran as CEO. Jeffrey was a founding partner of Adaptive Path, where he led the development of Measure Map, which was acquired by Google. At Google, he redesigned Google Analytics and led the Google apps UX team. Much earlier he was part of the founding web team at Wired Magazine.

Interview

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

Uh. (laughing) Do you know what I’m doing now?

Ryan: We know you are VP of Products at Adobe and oversee Creative Cloud…

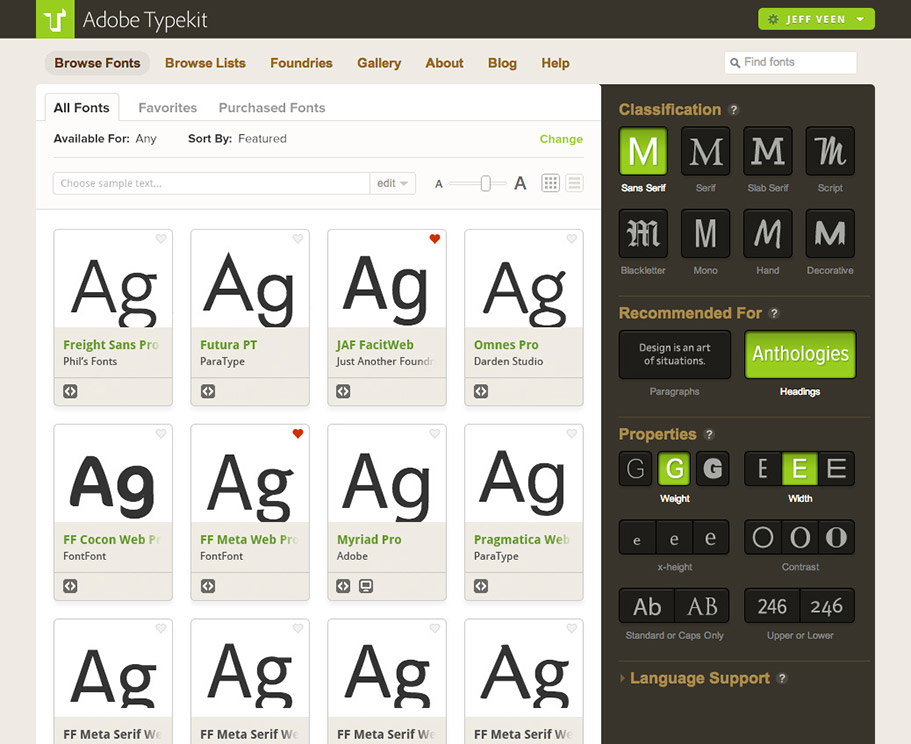

That’s right. Maybe I’ll start with what I’m doing now and work my way back. I’ll see if I can get all the way back to grade school. I, along with the rest of the Typekit team, have been here at Adobe for almost two years—it’ll be two years this October. Our time here has been remarkably good, which has the connotations of, “Oh, it’s going well for them,” and, “Huh, he sounds surprised!” Both are true. Integration into a company is super difficult—ask me more about that later—and we often hear about founders leaving a number of months after being acquired. But for us, the process has been great. Typekit has grown tremendously and our goal of putting web fonts on every website in the world is going better than we could have imagined.

We got involved with Adobe after three years of going it alone as a startup. We were growing quickly and had to make a decision about whether to keep going ahead on our own or come into Adobe. The timing was fantastic because we were at an inflection point. We had to get much bigger and there was the potential of having to do more venture capital fundraising, which we decided not to do. Adobe was starting the transition into Creative Cloud and that was exactly the kind of work we had been doing at Typekit. It was a great opportunity to try what we were already doing, but on a much broader scale. Now we have the ability to affect millions of people on behalf of Adobe. It’s been a fantastic challenge and I’ve learned a lot.

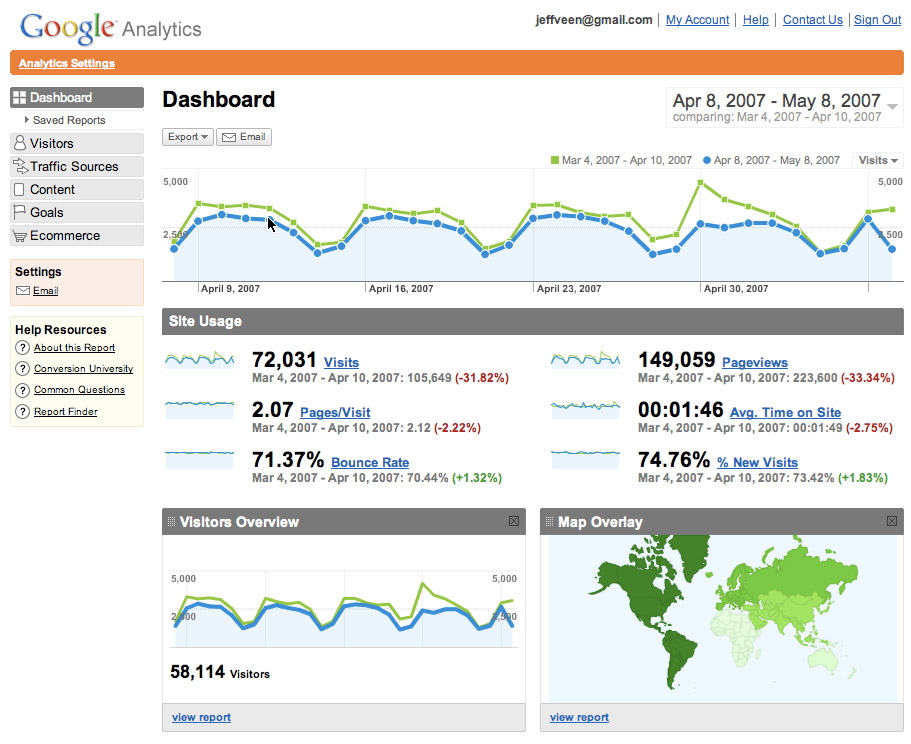

The path to get here has been a pendulum, swinging back and forth between bigger and smaller companies. Before Typekit, I was at Google; I got to Google because they bought MeasureMap, a product I had built at the previous company I helped found called Adaptive Path. We were a user experience consulting firm and I was a partner there—that’s where I learned that I didn’t really enjoy consulting. It was interesting because there was a breadth of problems to solve, but I never fully solved them; I never fully owned the problems I was working on. It’s a different thing to shape an idea, build a team around it, gain an audience, spend time getting to know your users, and grow a community—that takes time. No one is going to hire a consultant for three years to pull something like that off. Product development and leadership was where I wanted to go.

Before Adaptive Path, I was at Wired Magazine and built a lot of their online services. At that point of my career, I was in my 20s and didn’t know anything. It was good to be in an industry where nobody knew anything and we could figure it out together. And that’s my path.

Tina: Let’s take it back even farther. Was creativity a part of your childhood?

Creativity is part of everyone’s childhood until they learn—or are taught—how to not be creative. I have fond memories of being someone who told a lot of stories. In school, we’d be asked to write an essay about what we did over the summer and, inevitably, the teacher would read mine aloud, which I felt really proud about. That led to the assumption that writing and storytelling were things I was good at, and from early on, I loved the feedback I got from people. Going into technology never crossed my mind until the web came around—for me, the web was the humanities brought to computers.

Ryan: You alluded to this earlier when talking about Adaptive Path, but did you have a specific “aha” moment when you knew that product design and development was what you wanted to focus on?

Well, there was a specific moment when a very big client fired me. I thought things had been going really well, but then I realized that maybe I was missing some skills. I had not yet learned that sometimes the solution people want has very little to do with what they ask for; it often has to do with making them successful, rather than making their product successful. Adaptive Path was growing and I could have had the option to build a team around me, which is typically what happens in the agency world. One person becomes the creative director and has others who manage the clients and do the work.

One of the problems with consulting is that you only get paid while you’re actually performing the work. That’s wonderful from a profitability point of view and is a lot less risky than product development, but there’s potentially a lot less upside. The only way to increase the upside is to do what the two people who are important to you don’t like: charge your clients more and pay your employees less. No one likes that.

At the same time, I saw that people who had been consulting were starting to work on products—Basecamp was taking off and 37signals had their very popular blog. I liked the risk of product development. I liked the thought of taking an investment from somebody and saying, “Let’s give it a shot, but I’m not going to pay you back if it doesn’t work.” That is motivating! You put your reputation on the line. And it’s risky because you have to earn every dollar, but if you’re successful, it compounds over time, way more than billable hours. That was the mini-epiphany that led to asking why we weren’t trying products at Adaptive Path. I haven’t looked back since that.

“…sometimes the solution people want has very little to do with what they ask for; it often has to do with making them successful, rather than making their product successful.”

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Definitely. When I got to Wired in 1994, it was almost like an apprenticeship. They had a small website with plans to turn it into a whole line of business. I had likely managed to get the job because I applied via email with a simple URL, linking to an HTML résumé, which nobody had done before. That made me stand out of the pack, but then I had to prove I could do the job.

My knowledge of HTML caught the attention of the creative director, Barbara Kuhr. She was an amazing designer and needed to partner with somebody who could help her understand the constraints of this brand new thing called the web. She said to me, “You, with the HTML skills, take your desk and put it in my office. We’re going to build this thing.” This was before Netscape—we were building on Mosaic. She worked in QuarkXPress and Illustrator and I translated that into a web page. Through that process, we had to iterate and iterate and iterate. She’d take a pass and then I would; then she’d sit by me while I typed as fast as I could to move stuff around. I learned about visual hierarchy, colors, and all of the stuff I didn’t know before—and that’s literally how I learned to design. I worked with Barbara for five years and, eventually, I had my own team. I also learned how to manage a team from Barbara—you work for them. She was fantastic.

Ryan: You mentioned earlier that you had some thoughts on product management. Do you want to share those?

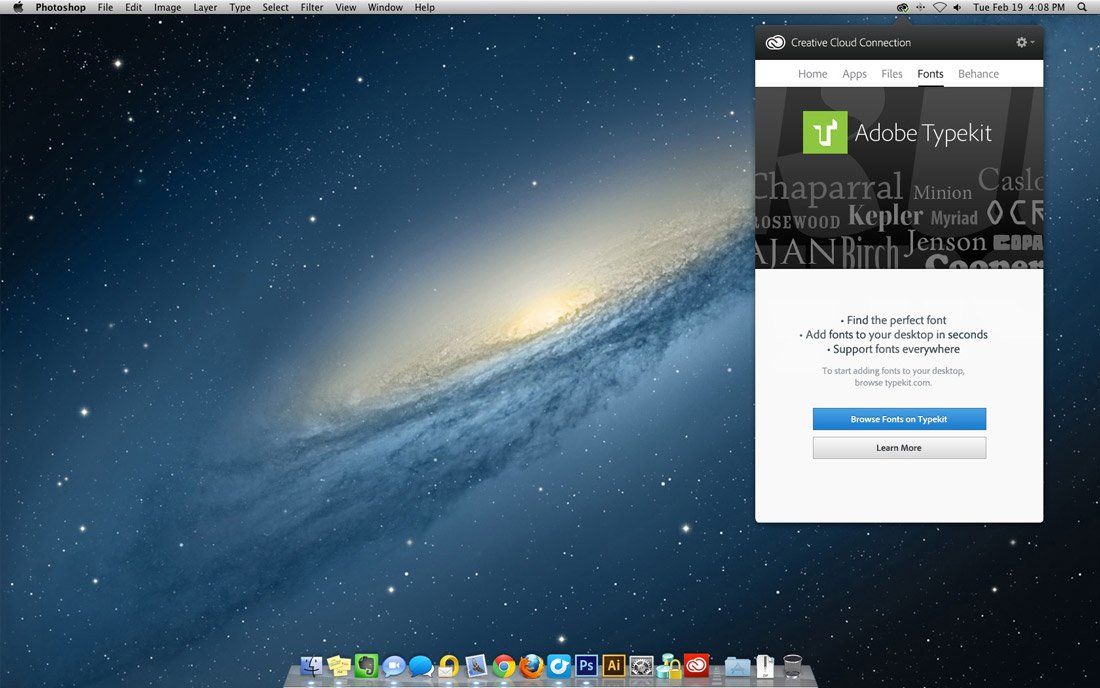

I’ve been at Adobe for about 20 months now and I’m still trying to figure out what product management means here. It’s very different from what it meant at Google and I don’t think it existed with what we built at Typekit because that role was spread out among a group of people. When I got to Adobe, product management was an awful lot about requirements and schedules and negotiations between different teams and departments. A lot of that stuff is just a result of scale. A way to get around that is to reduce the scale so you can reduce the complexity and have smaller teams that focus on simpler problems. One of the things we’ve been trying to do is stay more focused so that we can raise the overall quality by reducing the breadth of the offering. That’s difficult because Adobe makes products that span the whole range of what we call creative professionals and the crafts that they practice, from video to the web to photography. There are a whole bunch of tools, which is what the Creative Suite is—it has 30 products in it!

I’m fortunate in that I look after the cloud-based services that sit underneath all of that. I take the bits and pieces that you need to do creative work and make them accessible wherever you are. The goal with Creative Cloud is to make the process of creation frictionless and connected all the time. We just spent a year on the installer, which might seem crazy, but it’s about having your tools always available and up to date—stop fussing around with your computer and just do the work! To get back to your question, I really see product management as product development or platform development, which involves getting a group of people together to work on one problem for a while before turning their attention to another one, rather than juggling 70 priorities at once.

Has there been a point in your life when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward?

I think I’ve taken the same kind of risks over and over again. I’ve had some jobs that a lot of people would really, really want. The job where, once you have it, you’re set. I was a design director at Google and had a similar role at a company called Lycos, which bought Wired Digital. Those jobs have trappings like the perception of authority and a really steady income—but I left them because of the dissatisfaction with the work I was doing.

Leaving was terrifying. When I worked at Google, it was the first time my parents ever knew what I did. (laughing) Then one day I called my parents to tell them I quit my job. They had the same jobs for over 30 years and worked their way up to the American Dream: the kids, house, and car. Their kid finally had a good job, but quit it after three years. That’s risky. It’s even riskier now because I have kids and there are financial implications. However, one of the things I firmly believe about seemingly risky decisions is that you can’t fully imagine how things can be better while you’re in the thing you don’t quite like. That’s not advice; that’s personal experience—let me make that clear. I don’t want to tell everybody to quit, because I have a great team here and they’re going to read this. (laughing) But I get so focused on what I’m doing day-to-day that I have to be a little bit bored or scared. Anyone might love to take a month off, but after that, what’s next? I like that self-imposed pressure of figuring out what to do because that’s a constraint, and that’s where creativity comes from.

“…one of the things I firmly believe about seemingly risky decisions is that you can’t fully imagine how things can be better while you’re in the thing you don’t quite like.”

Are your friends and family supportive of what you do?

The problem is that most of my friends do this kind of stuff, so I don’t have much perspective on it. Most of my friends here tend to be entrepreneurs and creative professionals—for lack of a better term. In my city and yours, there’s a really big culture that considers going into a risky startup to be an incredibly viable thing to do. In other parts of the country, there are different societal pressures and taking that risk is a much bigger decision for people. Here, someone could have a job at a big company, but then decide to go freelance and his or her friends will say, “It’s about time! You’re awesome.” It’s a realistic option and taking the risk, despite the potential for failure, isn’t something that is looked down on.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I grew up very religious—that has changed, but I’ve held on to an awful lot of it, for better or worse. Not only do I feel a responsibility to give back, but I feel an obligation to always be doing something that’s bigger than me. That makes it hard to work on personal projects that don’t directly contribute to the world or generations to come, which can be exhausting and makes it difficult to start anything.

I often hear people talk about the fact that civilization persists because we share our experiences and teach each other so that we don’t have to relearn everything. I’m a firm believer that the technology we use daily exists so we can more effectively share—and that is a continuum that goes all the way back to people making marks in clay and letting it dry. We don’t have to be present to share information with each other; we can share ideas with people in other times and places, and we’re getting really good at doing that.

But I also believe that technology should contribute to the longevity of experiences, emotions, and ideas. That’s one thing we’re collectively really bad at right now—longevity. One of the reasons I wanted to do Typekit was to take the world’s content and free it from the constraints of things like images or other formats just to achieve style. That is incredibly important because it gives it longevity and makes it more accessible for people. Web standards-based separation of content and presentation is good for humanity, and Typekit contributed to that cause in a sliver of a way that we all found very rewarding.

Are you creatively satisfied?

I hope I never am—why would I continue to create if I was? But at the moment, I can’t think of anything to change. Right now, I get to work with some of the most talented people I’ve ever met in a culture that is tight and supportive—and only vaguely political—with what appears to be, after spending so many years in a startup, almost unlimited resources to achieve what we have set out to do. I put all those things together and it leads to a lot of satisfaction, though I don’t think you should ever be creatively satisfied. The only time I want to feel that way is when I’m recharging in anticipation of doing more stuff.

Speaking of recharging to do more stuff, is there anything you’re interested in doing or exploring in the coming years?

Well, my children will certainly be getting a lot of time and attention, but that’s also a similar investment in the future with the persistence of values to be passed on.

I do keep coming back to the problem of content longevity. We could potentially be in the middle of a two-decade digital dark age where companies are going to either make some decisions or go away. So much of what has happened that’s important to us is not in a shoebox under the bed—it’ll just be gone. We’ve already seen examples of this. We’re relying on the altruism of somebody else to ensure that the things we deeply care about persist. I actually think there’s a Wikipedia-level project in scope and size where we all collaborate to make sure that this digital wake that follows behind us is accessible, even when we’re gone. The enormity of that problem is mind-boggling, but critical.

“It was tough being an English major who was really into computers during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—a lot of people told me I was wrong about that, and I believed them for a long time…That’s a good lesson for a young person—it doesn’t matter what people think; be into what you like and follow it.”

If you could give advice to a young person starting out, what would you say?

Hmm. Well, there’s some really basic stuff, like don’t let anyone else decide what you’re into. It was tough being an English major who was really into computers during the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—a lot of people told me I was wrong about that, and I believed them for a long time. I was hesitant and embarrassed by it. I like the fact that we’re so connected now that we can find people who are into whatever we are, even if others think it’s weird. That’s a good lesson for a young person—it doesn’t matter what people think; be into what you like and follow it.

I am hesitant to say, “Follow your passion,” because I don’t believe in that. It has to be something that you are also good at and that the world finds valuable. I would love to go cycling all day, but the world does not find that valuable to the degree that I’m good at it. (laughing) If you get really, really good at something, then it will almost certainly turn into your passion.

I also think mentorship opportunities are huge. I would not be where I am today without someone who had taught me how to navigate the world of business and how to deal with adults. It’s hard to learn that on your own without burning bridges and really screwing up; you’re going to screw up anyway, but having a guide helps. I think that’s something to look for.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

I’m very, very fortunate to be in San Francisco—I did that deliberately 20 years ago because I could see that it was where all this stuff would happen. Also, that’s where Wired was.

On the good side, so much of the opportunity that we need to build great stuff comes from the people with whom we’re connected. My ability to build a great team for Typekit came from the fact that I didn’t have to interview the first 10 people. The core team who got us through the first year were people I knew through connections. And the opportunity of playing the game—of deciding that Typekit would be a venture-funded project—was just so much easier here. That’s not to exclude other places; you can do that elsewhere, but to do it here still gives an advantage. That makes it great to be here.

There are drawbacks. I don’t hang out with people who do other stuff. That is a huge boost to creativity—making connections that you would have never thought of. I try to do that, but a lot of my calendar is about networking and meeting with people who founded or work at startups. I don’t hang out with biologists or painters. I have to seek out and make an effort to find people who are not doing what I do.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Yeah. For sure. That’s the only way any of this stuff would work. One of the things I’m very pleased about at Adobe is that we acquired Behance a few months ago. Behance is the largest organized creative community and what they are doing is amazing. For all of the eye-rolling we do around social networks, you can take the signals from social networks and see the best work bubble up, regardless of network connections or geography. That macro view of community is amazing because there are talented people all over the world who haven’t had opportunities to drop everything and go work at a startup in San Francisco or sign onto an agency in New York. How do we uncover those amazing people and their craft? Behance has found a way to do that.

Also, having a small group of people I trust is really important. It’s easy to look at someone’s portfolio and see a perfect picture—it’s like online dating, right? (all laughing) But you don’t see any of the messiness that goes into making the work. Having a small group of people I can trust gives me a place to share the messiness of what I’m working on. I can say, “I’m working on this thing and it looks like shit! I don’t know what to do. I’m stuck.” I don’t go to a conference and say that, but that stuff happens. Sometimes there are periods of good momentum, but I also get stuck. That’s when it helps to have a smaller, more personal community, which is incredibly valuable as a way to be vulnerable with people I trust.

“I am hesitant to say, ‘Follow your passion,’ because I don’t believe in that. It has to be something that you are also good at and that the world finds valuable.”

What does a typical day look like for you?

Ridiculous. (laughing) The easy answer is that it involves a lot of meetings. The more difficult answer is that I try to find a balance between going fast and going slow. There are plenty of times when I feel unproductive, and that’s really important, but it’s difficult in a bigger company or corporation to just say, “No, I can’t do it. I’m going to go look out the window.” There’s a scene in one of the earlier episodes of Mad Men where Don Draper is sitting in his office with a glass of whiskey. Roger Sterling comes in and remarks, “Man, I pay you an awful lot and every time I come in here, you’re just sitting there, looking out the window.” Don responds, “Well, are you ever disappointed?” and Roger says, “No.” That’s part of the creative process and it’s hard to find time for that when there are 14 things to do in a 9-hour day. That’s why I’m so adamant about narrowing down our focus to what is most valuable to our users.

What music are you listening to right now?

I have the Sonos system at home and I’ve never listened to more music in my life than I do now. If I were to choose something to listen to in order to get into deep creative thinking and work, it will be ridiculously epic, post-rock instrumental music from the likes of Mogwai or Explosions in the Sky.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

Well, my favorite movie of all-time is Raising Arizona from the Coen brothers—you can take that for what it is. And my favorite TV shows are all the TV shows that are on right now because—holy crap!—they are amazing. I wish I had more time, but I like choosing to engage episode by episode. Right now I’m working my way through The Walking Dead.

Do you have any favorite books?

William Zinsser’s On Writing Well was a transformative book that I read my freshman year of college. Not only did it teach me about grammar and composition, but it also taught me brevity, editing, and clarity, which I’ve applied in my life in an unbelievable number of ways. It’s obvious to say less is more, but it’s more about getting down to the essence. Also, The Elements of Style goes hand in hand with that.

What is your favorite food?

Burritos—there’s a good essay I could write about the metaphysical incarnation of the burrito.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Ugh. We went from burritos to this?!

Well, I think we all probably aspire to make the world a better place. I was unbelievably fortunate to be beginning my work and practicing a craft during a time when there was so much opportunity surrounding this thing that has transformed the world. Nobody would disagree that the web has fundamentally changed everything. To be there at the beginning was—and is—an honor. I believe that any contribution I can make at this point in history is going to make things better, as long as I have the right values as I do it. It could be easy to say, “It’s a gold rush; let’s see what we can suck out of this,” and people do that, but, ultimately, participating without doing harm is the best we can hope for.

“I was unbelievably fortunate to be beginning my work and practicing a craft during a time when there was so much opportunity surrounding this thing that has transformed the world. Nobody would disagree that the web has fundamentally changed everything. To be there at the beginning was—and is—an honor.”