- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker June 11, 2013

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

James Victore

- artist

- designer

- educator

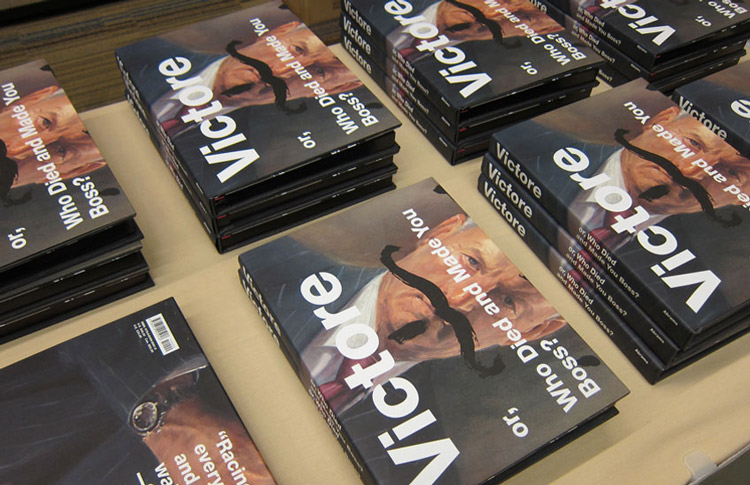

James Victore is an artist, designer, and educator who runs an independent design studio. His timely wisdom and impassioned views on design are shared through lectures, workshops, writings, and his popular weekly online series, Burning Questions. His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and is represented in permanent collections of museums around the globe. He lives, loves, and works in Brooklyn.

Interview

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

James: So the first question is going to be, “Where were you born,” right?

Tina: Basically, but I already know where you were born—in Idaho.

I was reared in the military and that means I’m not from anywhere, but yes, I was physically born in Mountain Home, Idaho.

Tina: See, I did my research.

Want to know something really funny? My name is James Brian Joseph Victore. Joseph is my confirmed name; it’s Italian and is also my father’s name. Brian is my second name because my mother, who has Irish heritage, wanted it that way. So I was born James Brian Victore, but according to my birth certificate, I am actually James “Brain” Victore because they spelled it wrong.

(hysterical laughter erupts)

So my wife, Laura, and I have this joke that she’s Pinky and I’m the Brain.

That’s awesome!

So, I was raised in the military and we moved around a lot, but I mostly grew up in Plattsburgh, New York, and consider that my hometown.

What was your path to what you’re doing now?

I was born to do this job. I was born to be a graphic designer. As a kid, I drew and made wordplay constantly. Malcolm Gladwell has this idea that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery at something. My 10,000 hours started when I was five.

Also, I was surrounded by art from an early age. My parents, who are very, very amateurish art collectors, were interested in an American artist named Maxfield Parrish and an American illustrator named Rockwell Kent. They collected what they could, which included magazine covers and things like that. My father was in the military and travelled most of my life. Every time he returned from traveling, he brought something back for me. Once, he brought me a toy from Japan and when I opened it, there were black and white batteries with kanji script on them; they were so beautiful and mysterious. My dad also brought back comic books that were very early versions of manga. He didn’t know it, but he was stoking this fire in me.

I also remember that my mother would take me dress shopping with her and when we’d leave the store, she’d look down at me and say, “Oh, Jimmy!” I was small enough to walk under the clothes racks and I’d pull the tags off of the clothes; I was curating things that were aesthetically pleasing to me. I guess I was either going to be a graphic designer or a cross-dresser. (all laughing)

The other important thing to note is that my mother worked in the reference department of the university library in the town where I went to school. We lived outside of town, so when I’d get out of school at 3pm, I’d go to the library for an hour or more to wait for my mom to get off of work. My mom needed to make me busy and she knew I liked to draw, so she’d put a stack of books in front of me—Graphis annuals from the 1960s and 70s, Italian design manuals, and art books. She’d also give me onionskin paper to draw on. I poured through those books, which gave me a huge graphic design history at age 11.

And what about high school?

I went to a traditional high school in Upstate New York with a graduating class of 90-something kids. I did well in high school because it was easy for me. I also did well on the SATs, but my verbal score was higher than my math. Because of that, I was an alternate for the Air Force Academy. Had my math score been higher, I would be a different person today. I always thought I would have made a good soldier, but that didn’t work out.

After high school, I had a great opportunity through my dad. He did a lot of different things to support our family after he got out of the military. One of the things he did for a short while was own a ski shop. Some marketer came by, gave my dad a card, and told him he needed advertising. My dad didn’t want advertising, but he gave me the business card and told me to go see who these people were. They were an agency in my town that did restaurant menus and fliers for dry cleaners. It was run by an old hippie who had worked at NASA. I ended up working for him and although I didn’t learn graphic design from him at all, he was a huge influence on me in all the good ways; he turned me on to Tom Waits and Bob Marley. I put together a portfolio while I was there and applied to art schools along the East Coast. I got accepted into all of them, but really wanted to come to New York to attend SVA because I fancied myself a poster designer and they had a history with posters.

At 19, I moved to New York to attend SVA and I had a 15-year plan: I wanted to be the best poster designer on the planet. I set out to do that, but once I got to New York, I realized there were no jobs for that. I was also a terrible student at SVA because my parents had no money and I had to support myself. When I took a job at a ski shop where I made $5 per hour, I thought, “What do I need school for?” I was chasing skirt and buying beer and I was the cat’s meow. It was great.

I was asked to leave SVA, so I did. In fact, Richard Wilde, who runs the graphic design program and is now a good friend of mine because I’ve been teaching there for 15 years, proudly says that he gave me a “D”. After I left SVA, I called one of my friends from the ski shop and he said, “Congratulations!” Then I called my dad and he said, “But I thought you wanted to be this famous art director?” I said, “Oh, yeah, I’m going to be. I still have that. I’ve just dropped out of school.”

When I was at SVA, I had an instructor named Paul Bacon, an amazing designer and jazz musician who introduced the “Big Book Look” in book cover design. He did book covers for classics that were turned into movies, like Jaws. If you go to an antique bookstore, it’s like a museum to Paul, who is still kicking by the way. He taught me so much about graphic design and after SVA, my entrance into design was through book covers. Seems fitting since I was practically reared in a library. It was the late 1980s and a good time for a young designer to make coin. I was working on five to six books at a time, sometimes for $3,000 a pop. I think it’s a much more difficult and less creative game these days.

Tina: Did you work for Paul?

Yes. I worked for him pre-computers in 1984, meaning I would do some of the mechanicals.

After I started out making book covers, I said, “Oh, wait. This isn’t part of my plan.” My plan was to be the best poster designer on the planet. At the time, there were only two jobs to do posters in New York: one was for Masterpiece Theater, but Ivan Chermayeff had that sewn up and the other was for the Public Theater, which Paul Davis was doing.

Then this situation came up in 1992. It was the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America and that’s when I did my first poster—the dead Indian. The reason I did it was because I was reading the newspapers, which were talking about all these celebrations around Columbus Day. I’m no idiot; I know a little bit about history. I know that as kids we learn that the Indians met Columbus, shook his hand, helped him grow corn, had Thanksgiving with him, and then you don’t hear about them anymore. I wanted to know why nobody was talking about the genocide. I had to do something, so I made a poster.

I didn’t have any money because I was spending it all on beer, skirt, and rent. One of those things had to go and it was rent. I printed 5,000 posters myself and paid to have them put up on the street. To make a long story short, every few months the buzzer would ring and I’d go downstairs to see a guy in a suit who would hand me papers and say, “You are served.” They were eviction notices because I was months late paying rent. I should have saved those notices to include in the book I wrote a few years ago because those eviction notices were the fucking cost of my freedom. Whatever you want in this world fucking costs something. I also had a girlfriend at the time; she didn’t like eviction notices—she was also the cost of my freedom.

By the time I was 32, I had found my dharma. I was making these posters, which allowed me to travel the world. In fact, all of my work that’s in the MoMA was made by the time I was 32.

Tina: So you were being paid to make posters by that age?

Well…

Tina: I’m asking for all our readers who are going to think you were off making posters and paying your bills doing that.

No, you can’t. No one gets paid to make posters, at least not much. There’s no money in making posters, but for me, it’s graphic design at its best. Now, where were we?

You left off at age 32. What happened next?

I made a big sin. I was building an international reputation, but then I turned my concern to commercial work and making money. And for ten years, I made money; I made commercial work that was good, but I wasn’t pursuing my dharma.

That brings us to Beacon, New York. My wife, son, and I had moved there and I was acting semi-retired. I spent more time pruning trees than making art, I had removed myself from my friends, and everything was falling apart. It was 2002 and I was regrouping because the business took an Internet turn on me and I didn’t know how to keep up. I had a big blow up, my wife and I got divorced, and I came back to New York. I continued to stay close to my son, who moved back to the city with my ex-wife soon after that.

After returning, I tried to get back to business as a commercial designer, but that didn’t work out because the budgets sucked. A studio like mine is efficient, does a ton of work, and we’re fun and easy to work with. We know how to make decisions, but clients will hire inefficient, time-wasting, wildly fucking expensive agencies instead. It took me a long time to figure it out. During those ten years from ages 40 to 50, I talked with all my friends and even if they were surviving, there was a glass ceiling. It was pathetic and embarrassing because we were all just slugging away.

During those years, I met my Laura, my wife, and we’ve now been married almost eight years. She’s very smart—deceptively smart because she’s cute and bouncy. She has grown immensely and has become a huge part of what we do at the studio.

Tina: So you two work together?

Yes, we run everything together and then there’s Chris—he’s an interesting story. I did advertising and marketing work for Portfolio Center and went there to speak about five years ago. Chris went to school there at the time and heard I was coming to speak. He managed a way to be my driver and we spent some time together. After that, he came and studied with me for a week through a workshop I did at the Art Directors Club. After the workshop, Chris said, “Hey, I’d like to work for you.” As I always do, I replied, “Well, if you find yourself in New York, sure, come by and we’ll talk.” Chris and his wife, who is a photographer, were living in Nashville at the time. He returned home and asked his wife, “Are you happy?” She said, “Eh, you know.” He replied, “I’m going to go work for James Victore. We should move to New York.” His wife asked, “Don’t you think you should ask him first?” He responded, “No, James already said yes.”

Now, this is really important. They moved to New York and Chris came knocking on my door. That day, TIME called for a cover job and we needed a photographer. I had Chris help me do the thing and his wife did the photography. After that, Chris worked for me for nine months without pay and now he’s being paid very well. What Chris did in his life—the chances he took and the price he paid to pursue his dharma—is really important.

Before Chris went to Portfolio Center, he worked as the Creative Director for a pastor at a megachurch in Nashville and that’s exactly what he does now—for me. He came here thinking he would learn to be a graphic designer, but we don’t do much of that. We’ve realized recently that Chris, Laura, and I make this happen together. Chris comes from a religious background; Laura’s interests are in feminine studies and women’s empowerment; and I’m interested in Eastern and Western philosophy and poetry. We use graphic design as the sugar coating to get our ideas across. All we’re doing is working with universal truths.

Ryan: You mentioned you’ve been teaching at SVA for 15 years…

Yes, I love teaching, but I’m going to be taking a sabbatical because I never realized that you should stop occasionally. (laughing) I asked to be a teacher at SVA early on and it took them years to accept me because my record there was so bad. Richard Wilde finally went to the boss and said, “Look what James is doing,” and they said okay. I’m a pretty good graphic designer, but I’m a much better teacher. I think I can make a better, smarter designer than I am.

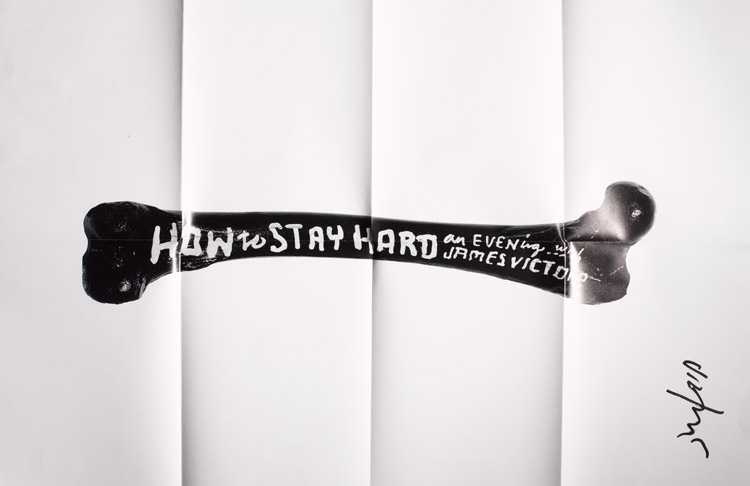

Now, we’re starting to use the word “teacher” in a much broader sense. I enjoy teaching, which is what I’m doing with our little Burning Questions film series. I should have started that much earlier, but my own stupidity, fears, and ego kept me from doing it. Laura finally pushed me to do it.

“We are firm believers in maxims, aphorisms, and sayings. One of our sayings is, ‘Your work is a gift.’ When you understand that, then it changes why you do it and who you do it for. You are no longer interested in the reward, the paycheck. Your job is not to make your boss or client happy because you understand that you have an audience beyond that.”

Did you have an “aha” moment?

I’ve had a number of “aha” moments, even now. That’s what it means to be in the now. We’re having “aha” moments all the time. One of them is that we can work as graphic designers without working for clients; that’s crazy.

(Laura, James’ wife, arrives and joins the conversation)

There have been “aha” moments all along the road, but I ignored most of them. Remember, I said I left my dharma to pursue commercial work? Then I floundered and couldn’t figure out how to get out of it. In my late 40s, Chris came into the picture. Then I met Laura and we got married. This woman [pointing to Laura] has been amazing and phenomenal in standing by her man as the song goes. She has believed in me and I owe her.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

Great ones. I met one of my early mentors when I was floundering in college for the first time—I forgot to mention that I had first went to the university in my hometown and was asked to leave that school, too. I had been waiting tables while in school and there was a chef I met—a wildly gay man in a town where there weren’t wildly gay men. His name is Gary Danko and he really helped me. He just pointed the way and said, “Young man, go to New York. You belong there.” Now, Gary owns a restaurant in San Francisco that you can rarely get into. Anthony Bourdain even mentioned him in the preface to Kitchen Confidential.

Henryk Tomaszewski, the Polish poster designer, was a mentor in spirit because I studied his work. I’ve now had the chance to meet and talk to him a number of times. One of Henryk’s students, a French designer named Pierre Bernard, was also a mentor. There was Paul Bacon, who I already mentioned. Even now, I’m always seeking mentors. We constantly try to be students here at the studio. According to Bob Dylan, “He not busy being born is busy dying,” right? I reach out to people constantly. Quite frankly, if we read a book and like the author, we try to get in touch. I’m working on Steven Pressfield right now.

Ryan: That’s part of what led us to start TGD. A friend recommended The War of Art to us.

What kinds of projects are you working on in the studio right now?

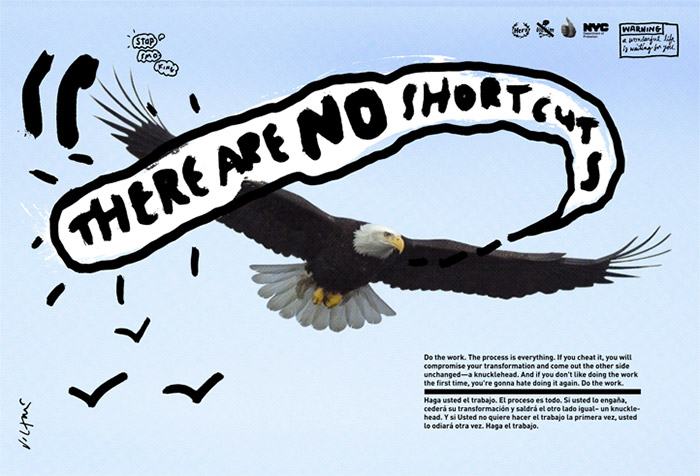

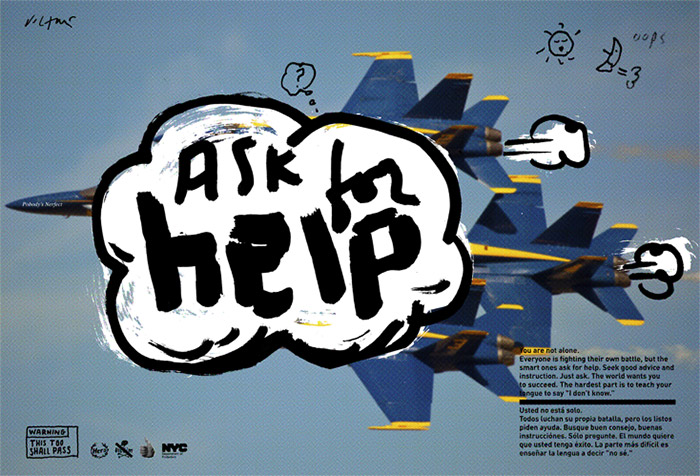

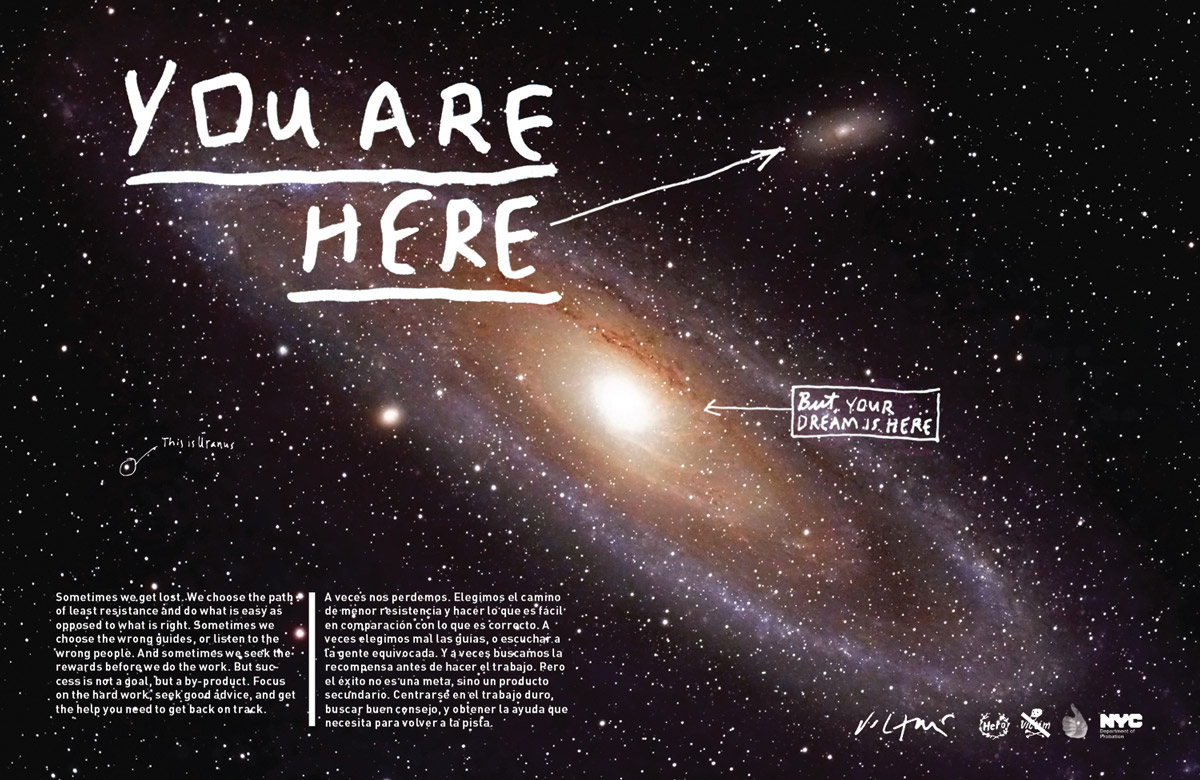

We have a totally new initiative that we can talk about, which is a job for the city of New York’s Department of Probation (DOP). The gig is like this—an architect pal got this job because the DOP got some money in their budget to redesign their resource hubs. They have 33 offices around NYC where, if you’ve committed a crime, but aren’t going to jail, you go to a resource hub, fill out papers, and wait in line. It’s hell—the carpet smells of urine, the ceiling tiles are falling through, and people talk to you through glass.

Tina: I was a social worker for many years and have been in offices like that.

The DOP was redesigning the hubs and had a timeline to spend the money. They asked Jim Biber to do the job and he agreed and signed me on for the graphic component to redo signage and paperwork. We looked at the thing and said, “Listen, these people need art in the offices,” so we made a series of posters for the DOP. We thought it would be really awesome if the posters were inspiring and motivating and we made them tongue-in-cheek by playing off of existing inspirational posters.

This one is the eagle—we’ve all seen this. But our eagle says, “There are no shortcuts.” Then, each poster has a little warning. This one says, “Do the work. The process is everything. If you cheat it, you will compromise the transformation and come out the other side unchanged—a knucklehead.” The last part is, “If you don’t like doing the work the first time, you’re going to hate doing it again.” We wrote it in a cool, stern fatherly tone. Plus we made up fake logos to make it look legit.

Tina: Are these up already?

They’re up! And we just got an email from the DOP that some of the probationers organized a group to write poetry based on the posters we put up.

Ryan: This is incredible.

Vince Shiraldi, commissioner of NYC DOP, said that when they redid the first few resource hubs, the clients would get off the elevator, walk into the room, and turn around and walk out—they thought they were in the wrong place. Do you know why they do it? Because they are not used to being treated with respect.

After the project went up, we did some interviews about it and people asked me what research I did in preparation. Research? I didn’t do any fucking research. As Chris says, “They are us, except they got caught.” We all want to be rewarded and treated with respect. You don’t have to design something if you tell the truth.

We also have a new initiative that we’re going to start called Cubicle Activism. People can sign into jamesvictore.com to subscribe and every month, we’ll make and send out hi-res, small format posters that are motivational for the cubicle culture. We want to help people realign their priorities and remind them why they’re working, because money isn’t the only goal. On top of it, we’re using MailChimp as our vehicle and with every poster, there will be an act. One of the first things will be to stop apologizing. Another might be to say no and take charge of your own personal revolution. We want to be catalysts for people’s courage and I think this is going to be some of our best work.

You’ve talked about risk, but has there been a point in your life when you decided to take a big risk to move forward?

I don’t think there’s a point in my life that I’ve ever decided not to take a risk. For better or worse, safety and comfort don’t interest me. To me, risk means feeling and being alive. Obviously, I don’t do stupid things, but I have to risk. I mentioned it earlier with Chris and his trajectory and Laura coming along in my life. I need to align myself with people who are game for risk because—and this doesn’t mean to sound high road—but we have to be the change we want to see in others and I need to align myself with people who understand their priorities. You know, I don’t say yes to everybody who wants to come by the studio and talk, but I looked at your stuff and you’re serious. I don’t want to waste my time on dickless motherfuckers.

(all laughing)

Ryan: That’s the best compliment ever.

Tina: And we’ve got it on record!

This relates to what you were saying about who you choose to surround yourself with, but are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Interesting idea. We lead our lives in a certain direction and understand that we have to keep pushing ourselves in certain ways. My own family doesn’t really have an understanding of how I live. When we change direction, especially when we started doing Burning Questions, the first wave of criticism came in from friends because that’s just how it works. If you don’t understand that, you’ll cave. Those friends are well-wishers; they are concerned for you and want you to be safe so they don’t understand what you’re doing and you can’t listen to them. We’ve had a good amount of criticism come from unexpected sources, but you have to understand that the resistance—to use Steven Pressfield’s word—is a test. Will you persevere? There is criticism and that’s why one of our stickers is, “Kill the critic.” I am my own worst critic. When I wake, I have to get up and do something right away or else my imagination starts going.

“I don’t think there’s a point in my life that I’ve ever decided not to take a risk. For better or worse, safety and comfort don’t interest me. To me, risk means feeling and being alive.”

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Your questions are timed perfectly. I already talked about my life between the ages of 40 and 50. I don’t want to paint a picture like my life was in shambles, but I was trying to figure out how to make it as big as possible as a commercial graphic designer and do the best work on the planet.

After that, Laura came into my life and really helped my blood pressure and attitude. I used to kick furniture and scream, but I don’t anymore. Then Chris came into the game and added something else—this is all totally part of the question. The “aha” moment I had is that my work is no longer about me. I’ve done a fair amount of commercial work that’s been accepted and I’ve had two shows in the MoMA, which I can leave on my resume to linger forever, but the most important work I’m doing is what we’re doing now. Our work is not about us. The reason we’re looking for sponsors is because we can’t get paid to do this work, but it’s important and it has to get out there. I want to make graphic design work that has huge ideas embedded in it, ideas that will help other people and give them the skinny so they don’t have make the same mistakes and be a dick like I was. The idea that we can use graphic design to help people is kind of awesome.

We are firm believers in maxims, aphorisms, and sayings. One of our sayings is, “Your work is a gift.” When you understand that, then it changes why you do it and who you do it for. You are no longer interested in the reward, the paycheck. Your job is not to make your boss or client happy because you understand that you have an audience beyond that. And I think that goes for anyone doing any job.

For us, our work is a gift. The two biggest projects we have going out the door are Burning Questions and Cubicle Activism, which have to be free. Now, if we can find a sponsor to give us 2 million to research and involve other people, that’s great. The next level for us is to be able to sponsor other people. This is out of Deepak Chopra’s notebook: If you want love, you have to be and give love; if you want attention, you have to pay attention; if you want money, you have to help other people make money. This was my stumbling block from ages 40 to 50 because I was just looking to get paid. Then I let go of that and said my work is no longer about me.

Ryan: That was one of the biggest realizations for me and why we do TGD. We derive the largest amount of satisfaction from encouraging people to do the things they love and are passionate about. I hope we can be a catalyst for helping others to do that.

“Don’t chase money because then you get so caught up in what shit costs and…that shuts the rest of our lives down. If you’re a graphic designer who wants to make a lot of money and do good work, there’s a good chance that you won’t do either…”

Are you creatively satisfied?

No. Who would be? That’s crazy! Does anybody say yes to this question?

Yes, but there’s usually a caveat.

No, it’s impossible to be satisfied! Like the other night, Laura was doing something in the kitchen and she found me; I was sitting over there on the couch, tapping my finger on the posters on our wall. I said to her, “I’ve been searching for great my whole life. These posters are fucking good.” This is what I’ve been working for—a client to validate it, an audience. We’re onto something, but I want so much more.

I recently did a talk in Cincinnati. It was a small conference combined with a museum show and some of my friends were there: John Burgerman, Joshua Davis, Sara Blake. I couldn’t stay for the museum show because I was on a junket of too many talks in too few weeks. Joshua had dinner with a guy and asked him, “So what did you think?” The guy replied, “Oh, I liked this and this, and that was really cool, but I didn’t like James Victore’s talk. I brought my creative team to the talk and now I’m worried they won’t show up on Monday morning.” That’s the best validation of the work. I want people to be unsatisfied, to realize it, and own up to it. The Great Discontent—you have to tell me this story now. Where does the name come from?

Ryan: I’ve always been wrestling with wanting something more and have never really been satisfied with what I’m doing. I’m constantly driven to do more and to challenge myself.

Is there a literary reference?

Ryan: Not that we know of. In talking with one of our personal mentors, he said, “You have to learn how to be content in your discontent.”

Tina: That was not the answer we wanted.

Ryan: I thought about it and it made sense. Your discontent drives you forward, but you have to learn to be okay with that feeling.

Laura: That reminds me—we just did a Burning Questions called “You’re Not Entitled to the Fruits”. You’re not entitled to the end goal; it’s about the journey. If you’re not enjoying that, you’re screwed.

James:If you’re in it for the wrong reason, that reason will fuck you.

Ryan: And it usually has to do with money.

Or any kind of reward or fame. No amount of fame feeds this thing. It has to come from the inside. I don’t work for money. I’ve never worked for money. Don’t chase money because then you get so caught up in what shit costs and what we don’t realize is that shuts the rest of our lives down. If you’re a graphic designer who wants to make a lot of money and do good work, there’s a good chance that you won’t do either of those things.

That’s true. If you could give a piece of advice to a young person starting out, what would you say?

It’s always the same. Never give in. Never surrender. What I have to add to that is, it will be worth it. Early on, we have a vision of the way the world should work—don’t let go of that because it gets co-opted. Advertising talks to you; practical and reasonable start talking to you and they will fucking kill you every time.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

I’d like to say zero. I live here, but don’t think of myself as a New Yorker because I’m not a liberal, bleeding heart and I don’t read the New York Times. I’ve always thought that I did it the chump, easy way by moving to New York. What’s available in the museums here doesn’t influence me, although being here in New York and having my pals, who I can go surf with or have beers with, does help. Doing this from Des Moines would be kind of hard, even though the Internet brings everything to our fingertips. If you have the balls to go read a book of Steven Pressfield’s and send him a note about it, he might write you back. Could I do it in Des Moines? I don’t know. I’m scared shitless about the idea that, within some span of time, we’re going to make the jump from here. Where does Steven Pressfield live? (laughing)

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

You know, I don’t want to be bitter. It’s my own sad pile of beans, but I feel that my timing was bad. I got involved in this business because I wanted to be like Milton Glaser, but the business and industry changed. The Internet, quite frankly, has not made it more creative, but it’s made it more diverse, which is groovy. There’s a certain part of me that’s upset that the business changed, but I’m not a complete idiot and I’m riding with it. We have certain goals and we’re meeting people because of the Internet, so it’s great for us.

Laura: In regards to that question, I was going to add that we recently had an interesting conversation with new friends about the fact that everyone is creative to some extent. In that sense, surrounding ourselves with creative community is really important. Even our neighbors are so inspiring. They’re not designers, but one is an amazing photographer; one is an animator and filmmaker; another is an architect who is doing a huge public project. It’s hugely important to us to not limit ourselves just to the graphic design world.

James: We have an extremely smart intern named Collin, who is going to spend the summer with us. He’s like an excited puppy and wants to learn how to do everything. He’s an amazing guy and I’ve taken him aside already and said, “Dude, I love your spirit and energy. You have an interest in all these things that you’re already bringing to the party. You’re getting us excited. Do you know why we’re going to take you on as an intern? Because I see a spark and thing in you. By the way, down the road you are going to be in an interview situation and if you don’t say ‘James Victore’ in the interview, I will fucking kick your ass. I want to be part of your revolution.”

“Early on, we have a vision of the way the world should work—don’t let go of that because it gets co-opted. Advertising talks to you; practical and reasonable start talking to you and they will fucking kill you every time.”

That’s awesome. What does a typical day look like for you?

I don’t even want to tell you.

(all laughing)

Laura: It’s pretty good.

James: Laura and I write coffee notes to each other. Coffee notes happen when I wake up early in the morning or Laura preps coffee before we go to bed and all I have to do is press the button to make coffee in five minutes. There are two things involved here: 1) The notes are our own little personal practice in making stuff 2) It’s practice almost every day telling a very specific person that you love them. All of our work should be coffee notes. We have boxes full of these notes, which will turn into ideas for Cubicle Activism because they’re funny and goofy.

I try to get up very early every morning. I exercise. Laura meditates and exercises. We both try to read in the morning to sharpen the saw. We eat breakfast together when we can. Every Wednesday, I drive my son to school and he’s with us on the weekends, too. He’s in high school now so he’s got his own fucking schedule. Although, it’s important to him that I’m there for all his soccer games, and I love that he needs me there.

Chris doesn’t show up here at the studio until 11ish, partially because he drives and there’s no parking on the street till after 10:30am. That gives me time to work on other stuff, like writing, which I sometimes do at the coffee shop. When Chris comes, we try to get shit done. Sometimes we have lunch outside the studio with an agenda and we always bring pens because good ideas come when you’re not trying. If Chris is still here at 6pm, that’s a late night.

Laura: We try to work super concentrated. If it’s a good day and we get a lot done, then the guys go play pool around 4:30pm and I have a little time on my own.

James: Yeah, Chris and I will go play pool from 4:30–5:30pm. Again, I always bring a pen. Then I’ll come back and Laura asks me what I want for dinner and I never have an answer.

Laura: So I just have to make it up. I don’t know why I ask anymore. (laughing)

James: I’ll have the same thing every night. I don’t care. Anyway, Laura and I will have a yummy little evening together. I’m an early to bed, early to rise kind of guy so I go to bed pretty early. Our days are simple and I like that. Sometimes we have meetings and whenever we do, I like to schedule them around food because I think that breaking bread with others is an important event. Sharing wine and whitefish with you guys has helped tremendously.

Indeed, it has. What is your favorite music?

(Laura begins laughing)

Tina: She has a really good answer for this. We want to hear it.

James: Can I play it?

Laura: Which one? There are two.

James: I would play Christmas music forever. I am the most nostalgic motherfucker. I have other music that I love, too. Musically, we’re in a transition because we used to do CDs on the stereo, but again, the Internet is changing the way things work. I have my guys who I listen to: Johnny Cash, Neil Young, Bob Marley, and Bob Dylan. The reason I listen to them is because they point me to North. I also love classic rock, classical music, and a lot of different things. Laura opened me up to gangster rap. Music is a great example of what Laura has taught me, which is the importance of balance. I like Johnny Cash and the truisms of country music, but I also understand the balance of throwing a little Ludacris in there. But I think I’m a fan of drinking and playing pool because of what Johnny Cash and Dwight Yoakam have done to me.

Laura: But there’s one particular song he loves that he likes to play over and over again and I’ve put the kibosh on it—it’s “Turn the Page.” He recently went through a phase with another song, too.

James: Oh, yes, it’s an awesome and important song. Wait, I’m going to put it on. [James makes his way over to the computer] I think this is the one you’re talking about. There’s always a song in my head when I wake and when we were starting one of our dinner workshops, I woke with this song in my head out of the blue. I listened to it and realized that 1:32 into the song was brilliance. I played it a bunch of times and it was perfect. I even played it for my dinner workshop guests and now I am going to inflict you with John Oates and Daryl Hall.

(James hits play and Hall & Oates’ “Sara Smile” starts playing. We wait until 1:32 into the song.)

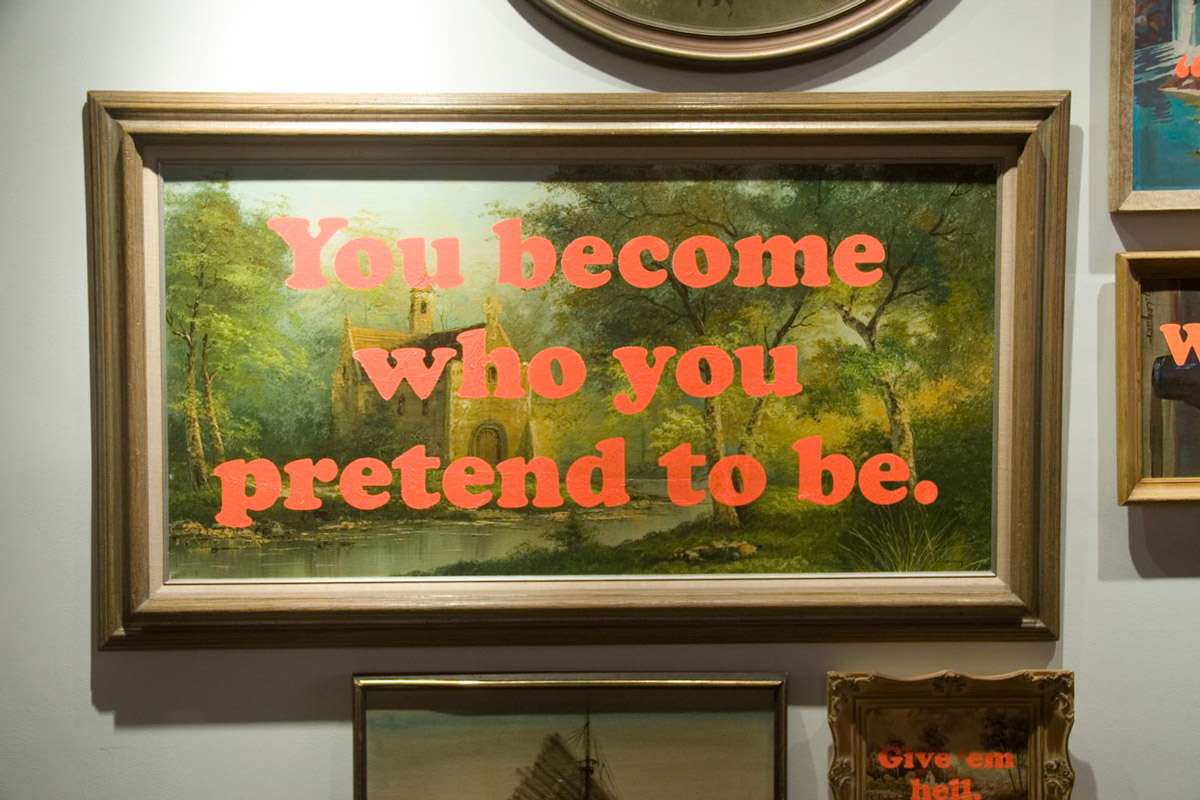

This is the line: “If you wanna be free, all you gotta do is say so.” This is fucking huge. Over a year ago, I started pretending to be someone who I wasn’t. Today, I find myself living into that person.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I want to make things happen for other people. I don’t have a concern about my work living past me because that was done a bunch of years ago. My work is in textbooks and museums, which is weird. Now, I want to make stuff happen for my wife, my son, and my students.

“I listened to it and realized that 1:32 into the song was brilliance…‘If you wanna be free, all you gotta do is say so.’ This is fucking huge. Over a year ago, I started pretending to be someone who I wasn’t. Today, I find myself living into that person.”