- Interview by Tina Essmaker April 2, 2013

- Photo by Henry Leutwyler

Louise Fili

- designer

- illustrator

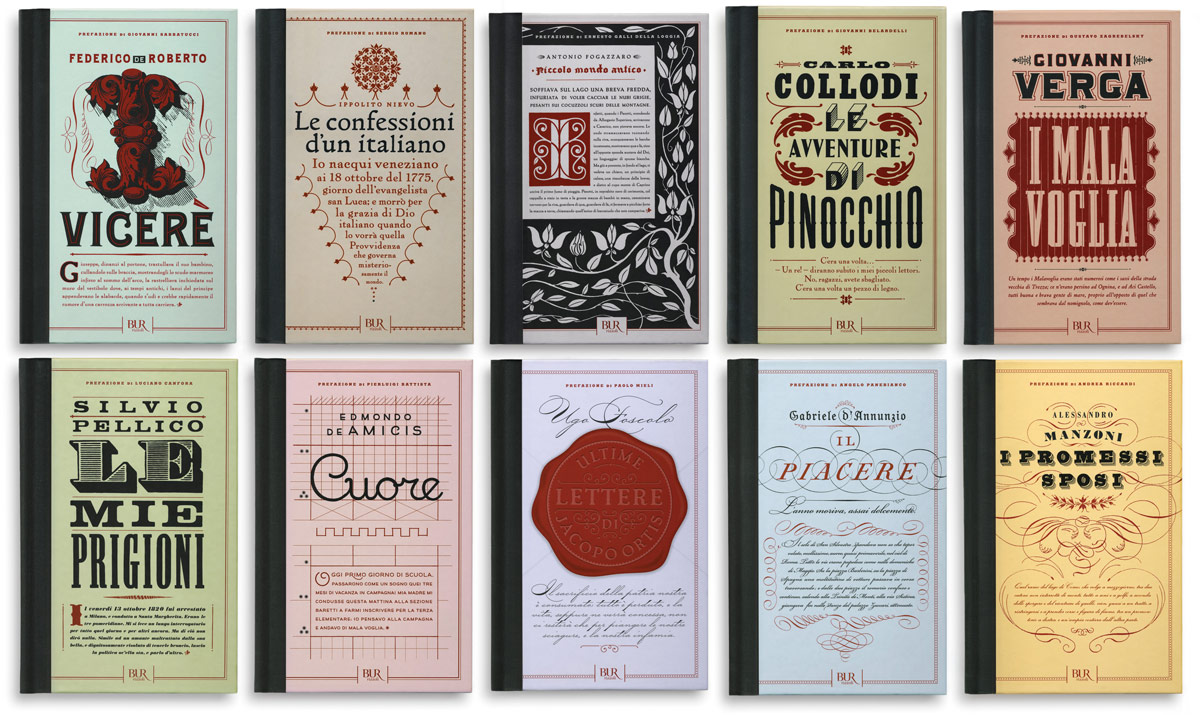

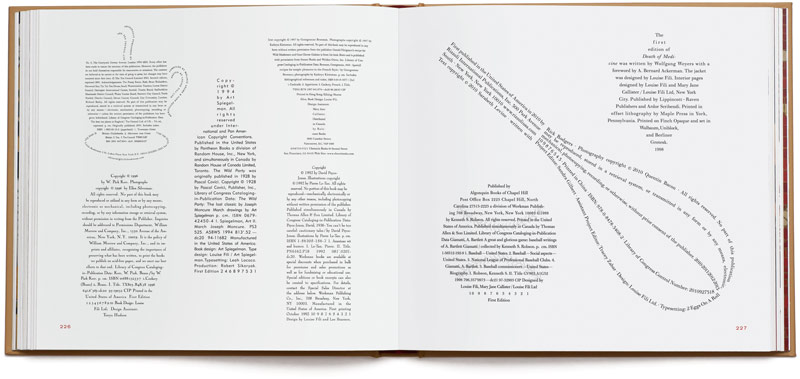

Louise Fili is a New York-based graphic designer and founder of Louise Fili Ltd. Formerly senior designer for Herb Lubalin, Louise was art director of Pantheon Books from 1978 to 1989, where she designed close to 2,000 book jackets. Louise has taught and lectured on graphic design and typography and her work is in the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, and the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming a graphic designer.

I was always fascinated with typography. I remember being four or five years old and carving letterforms into the wall above my bed, even though I didn’t yet have the ability to form them into words.

When I was in high school, graphic design was called commercial art, which was a pretty unsexy term. During those years, I sent away for an Osmiroid pen, which was advertised every week in the back of the New Yorker magazine. With that, I taught myself calligraphy, still not understanding that this would have any relation to what I’d be doing later in life.

That same summer, when I was 16, I took my first trip to Italy with my parents, who were both born there; it was their first trip back. I remember taking a flight into Milan, and as we were leaving the airport, the first thing I saw was an ad for Baci Perugina—that was the only type on it. I was immediately fascinated by the billboard, which showed a couple in a passionate embrace. I knew that Baci meant “kisses”, but I didn’t know that it was advertising at all. It didn’t matter; I was smitten. It was a three-way epiphany for me because that’s when I fell in love with type, food, and Italy all at once. I still didn’t know what graphic design was, but I would find that out later.

Were you born and raised here in New York?

No, I was born and raised in New Jersey, which I never forgave my parents for. I’ve lived here my whole adult life, though, so I consider myself to be a New Yorker.

Where did you go to college?

I went to Skidmore College where, if you couldn’t paint, they told you that you were graphically oriented. That’s when I found out what graphic design was. I was very lucky because my painting professor also happened to be the graphic design teacher and he took me under his wing. That’s when I discovered that all the things I was interested in—letterforms, calligraphy, and books—were of interest because I loved graphic design.

Did you then study graphic design?

Yes, I did, but I realized that I needed to get out of there quickly and come to New York because, in those days, that was the only option if you were seriously interested in graphic design. In the middle of my senior year, I came to New York and wrangled my way into working as an intern at the Museum of Modern Art as well as taking a semester of classes at the School of Visual Arts. I never finished the semester because I found a job and, at that time, SVA had a policy that if you found a job before finishing school, they would give you credit and let you graduate. It was kind of bizarre because SVA had to give me credit for the semester, which in turn Skidmore gave me credit for and then, to my great amazement, I finally ended up getting a degree, which has never really done much for me.

I soon found myself employed by Herb Lubalin, who was a wonderful mentor. That was the place to be if you were interested in type because you were living and breathing type every day. Being there was a remarkable experience.

“There were a few things I did know when I started my studio. I knew I wanted to keep it small and I always have…And I really wanted to focus on the only three things that interest me: food, type, and all things Italian.”

What year did you come to New York?

I came here in 1973. Actually, before I worked for Herb, I worked on special project books for Knopf. I was brought in to work with a high-profile British documentary filmmaker, Midge MacKenzie. She had just put together a Masterpiece Theatre series about the women’s suffrage movement in England, and this would be the book to tie in with the series on PBS. She had stipulated in her contract that she needed to work directly with a designer. I had never designed a book before and the art director who hired me was more concerned about my ability to get along with an author than he was about my design skills. So, we were put together in an office and nine months later, to everyone’s surprise, we emerged with a finished book. That was a great experience because Midge had the eye of a filmmaker, and I was able to gain an entirely new perspective from working with her.

After that, I went to work for Herb. I was there for two years and realized that even though I went there to get away from doing books, I actually loved designing book covers. I left there and was hired as art director at Pantheon Books, where I stayed for 11 years. That’s really where I found my design voice. The great thing about working in book publishing is that you can experiment with different periods of design history on a daily basis. I wasn’t interested in using existing typefaces; I wanted to design my own. And because Pantheon had a very Euro-centric list of authors, I was able to develop my interest in type and design history.

My interest in type and design history started when I was working for Herb because one of my clients there, Harris Lewine, was an extraordinary art director in book publishing. He had the distinction of having been fired from every job position he had ever held. With his encyclopedic grasp of design history, he taught me the importance of using historical reference as inspiration. Ultimately, I created my own archive by going to Europe on a regular basis—at least twice a year—and collecting reference from flea markets, which became the basis for everything I’ve done since then.

When you worked at Pantheon and started designing your own type, was anyone else doing that?

No, this was when phototype was just starting to happen and before that, everything was set in hot metal. Everybody wanted to use standard fonts, but I just wasn’t satisfied doing that. I didn’t realize this until years later, but what I was really doing was developing type treatments for the title of the book and approaching it more like a logo. I wanted each book to have its own personality and that couldn’t be achieved with standard fonts. Again, I was lucky because it was appropriate to do that for the types of books I was working on. The other thing to note is that I was collaborating with a lot of really talented illustrators and made a concerted effort to combine the type and image together. I also tried to encourage illustrators to create their own type. I would sketch it out for them and then ask them to actually draw it so it would become part of the illustration, which makes for a stronger design, whether it’s a book cover or logo.

And it was after Pantheon that you started your own studio?

Yes. I was at Pantheon for 11 years and never had any desire to start my own studio because I never thought of myself as having good business sense. However, I did get out at just the right time, which I seem to have a knack for. I believe in leaving the party while it’s at its peak. So I left, and sure enough, six months later, Pantheon had a total upheaval because my editor-in-chief was fired and all the other editors left in solidarity.

When I started my own business in 1989, I didn’t know very much about how to do that. Thankfully, because I had been working in publishing for so long and the art directors were so poorly paid that they all freelanced for each other, I already had clients. However, I was aware that I shouldn’t depend on any one type of work or client because I just knew that it wasn’t going to last forever.

There were a few things I did know when I started my studio. I knew I wanted to keep it small and I always have; I still only have two people working for me. And I really wanted to focus on the only three things that interest me: food, type, and all things Italian. In the beginning, it was tricky to make inroads into the food world because it’s so very different from publishing. I started with restaurants and learned quickly that the kind of people I was dealing with were just short of gangsterdom.

Especially in New York, right?

(both laughing)

Yes, especially in New York. I also learned that restaurants are the number one business most likely to fail in New York City. It was an interesting learning curve.

Have there been any milestones along the way?

Well, I started my studio out of my home. I’d always had a studio there because of my freelance work. Right after my son was born, while on maternity leave, I started working at home with every intention of later returning to Pantheon. However, when I went back to work, I thought, “I don’t want to be here.” Since I had the studio and the clients, it was a very easy transition. Working out of my home allowed me to see my son whenever I wanted to, but I could also work uninterrupted if necessary because I had help. I did that for two years and then realized that it was time—we all needed space, so I moved into a separate studio space.

I’ve always kept my studio in the neighborhood, which has been very good for me because I like to walk to work. My current space is the furthest I’ve ever been from home and is about a 20-minute walk, which translates into two miles a day.

Was creativity part of your childhood?

My parents, who were very old-world Italian, were immigrant schoolteachers and couldn’t make anything out of my interest in art, so I was really on my own, which I think is just as well. I learned to navigate around my interests in art and books. On Saturdays, I used to go to the public library and spend the day there, reading and looking at books, although as I recall I wasn’t just looking inside—I was studying the covers, too. I enjoyed the whole tactile quality of books.

What I did get from my parents, though, was this love of food. In an Italian-American household, food is the religion. I thought everyone’s parents woke up every morning and talked passionately about what to make for dinner that night. It is still my eleventh commandment.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

Well, yes, the professor that I mentioned having in college was a mentor. Not only was he sympathetic because he taught graphic design as well as painting, but he was also Italian-American. He was my advisor on an independent project, which, ironically, was a completely hand-lettered Italian cookbook with no imagery—only type. I still remember him being more critical of the recipes than the design. I knew I had to get it right or I wasn’t going to graduate. (both laughing)

After that, Herb Lubalin was a mentor, of course, but even more important than him, was Harris Lewine. He really opened up this whole world of design history that was unknown to me at that time because my soon-to-be husband, Steve Heller, hadn’t yet written the books he would write on design history.

Wait a minute, you’re married to Steve Heller? I guess I didn’t do my research.

(both laughing)

I’ve been married to Steve for 30 years and we met because he wrote me a fan letter, which is reproduced in my book, Elegantissima. At the time, he was art director of the New York Times Book Review and I worked at Pantheon.

So, you met each other in person after the fan letter?

Yes, and a year later, we were married.

That’s amazing!

Was there a point in your life when you took a big risk to move forward?

I guess the biggest move for me was deciding to go out on my own, but at the time, it didn’t seem like a big deal. It seemed very natural and it was because, as I mentioned, I had the clients and I didn’t have to look for an office space because I could work from home. I suppose I’ve done everything in my career gradually and when things feel right, I make the moves. When I have a sign, I leave.

A good example of that is what happened with Herb Lubalin. I had been working with him for two years at his legendary studio where I thought I would stay forever, but then he decided to move to a new space. We had been working out of a beautiful converted brownstone and I had a sun-filled private office. Herb decided to buy a converted firehouse, which was stunning, but soulless. To make things worse, I would be moving to the basement—no windows. I took this as a sign to move on. I went to see my former boss at Knopf and he happened to mention there was a job opening. I asked if there was a southern exposure in the deal. He said yes. I took the job.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Absolutely. Steve and I collaborate on many projects together and what’s so wonderful about that is that he is such a prolific and accomplished writer. When we work together, we each do what we’re good at. He does the writing and I do the design and there’s no conflict; it’s a very good fit. We’ve worked on projects that I probably never would have had the ambition to do on my own, but collaborations offer an extra dose of energy and inspiration.

“I believe that every designer has to have personal projects—it’s the only way to grow and find a unique voice. At any given point in time, I’m working on an independent project in the studio and that’s very important to me—it’s what defines me as a designer.”

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

One thing that was very unfortunate for me when I was in school and just starting out as a designer in New York was that I had no role models. I couldn’t find any women working in the field of graphic design—and I tried very hard to find them. Today, it’s really, really important to me to be a role model in any way I can. I’ve been teaching at the School of Visual Arts for over 30 years, where most of my students are female. Many of the employees I hire are women as well.

Are you satisfied creatively?

On a good day, I’m 90% satisfied, which is fine; I don’t think one should ever be 100% satisfied because then there is nothing left to aspire to. I always like to have that 10% that keeps me moving and thinking about the next project that I want to do.

I believe that every designer has to have personal projects—it’s the only way to grow and find a unique voice. At any given point in time, I’m working on an independent project in the studio and that’s very important to me—it’s what defines me as a designer. Right now, I’m working on a book of my photographs of Italian signs, which I have been taking for over thirty years and am very passionate about. I have the photos on a dedicated shelf in my office, arranged in binders by city, and they’re an incredible source of inspiration for me. I started taking them as 35mm slides, switched to a point-and-shoot camera, and eventually went digital. I never meant for them to be anything but reference, but now that the technology is more advanced, I can make them look better. That’s also ironic because, thanks to technology, a lot of these signs are disappearing and are now dumbed down to mediocre type and cheap plastic.

I actually took time off between December and January to go to the American Academy in Rome so I could have an entire month to photograph all the signs in Rome. It was heaven.

How often do you go back to Italy?

As often as I can. I use any excuse to go. This year, I’ll be traveling there three times, which is just right.

Do you still have family over there?

I lost track of them, unfortunately. My father was from Sicily and my mother was from Calabria, which is the toe of the boot that’s kicking Sicily.

Is there anything you hope to do or explore in 5 to 10 years?

I think I just want to keep pursuing personal projects and fueling my interest in going to Italy as often as possible. Within the last ten years, I’ve done a number of my own books. I started doing books with Steve and then, when I started designing covers for The Little Book Room, publisher of specialized travel guides, mostly for Italy and France, they asked me to write and design a little guidebook to artisan shops in Florence. I said, “I am neither a shopper nor a writer,” but apparently it didn’t matter. It doesn’t take much for me to get on a plane to Italy to go interview shopkeepers and taste test gelato. I was really glad that happened because it was something I had never done before and it forced me to use another side of my brain. After I did that, I was asked to do a book on “what makes Italy Italy”, so I did Italianissimo—the only way I can describe this book is that it’s all the things we love and sometimes love to hate about Italy. One book led to another and now I’m doing the sign book.

If you could go back and do one thing differently what would it be?

Maybe I should have learned how to design on a computer. (laughing)

Do you use a computer at all?

No, and I prefer it that way. Most designers of my generation are equally technology-challenged. For me, the excitement is doing sketches. My sketches start out being very rough and then get very, very precise. Then I’ll go gather reference, sit with one of my designers and go over it carefully, and supervise the execution of it. We try very hard to make sure things don’t look like they were made on a computer.

What advice would you give to a young designer starting out?

Follow your heart. You have to combine design with passion, otherwise, there’s no reason to be a designer. It’s not a way to get rich—at least I’ve not found it to be. But doing it is what makes me happy. At this point, my work and my life are totally, inextricably combined—you can’t separate one from the other and that’s just the way I like it.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

Well, in an ideal world, I would be living in Europe, but that wasn’t meant to happen. And I have to say, if I had moved to Italy, I don’t think I ever would have been able to do the work I’ve done. I love living in New York and it’s the only city in America that I would want to live in as long as I can travel to Italy on a regular basis as a visitor. I think that is a much more practical way of enjoying Italy because living there can be incredibly frustrating, especially when trying to get anything done, which is why many good Italian designers have moved here.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Of course. Absolutely. Going back to my art directing days, being able to work with great illustrators, photographers, and retouchers was so important and that’s the wonderful thing about being in New York.

Are your friends mostly involved in the creative industry?

Yes, because that’s the only language that I speak. I have friends who are outside of design, but it’s much easier to associate with people who understand and appreciate what designers do.

What does a typical day look like for you?

First, I wake up around 6am and try to find a reason not to go to the gym. Sometimes I can’t find one, so I’ll go. Then I walk to work and stop by the farmer’s market on the way, which is an important part of my day. I get to work around 9am and will typically have a few meetings with clients here at the studio. I only take on clients who have products that I really believe in. As I mentioned, I have a small staff, so I work very closely with both of my designers. Actually, I described my perfect day in my book, Elegantissima. I’ll read it to you:

“Here is my perfect brand-name day: dressed in Ilux, I have breakfast courtesy of Irving Farm Coffee Company and American Spoon, I walk to the studio carrying a Blue Q tote, work until it is time for a pick-me-up of Q.bel chocolate or a passion-fruit sorbetto from L’Arte del Gelato, have a glass of Calea Nero d’Avola at apertivo hour, and stop in at the Mermaid Inn for a lobster roll on the way home. Small businesses make good business.”

That’s my perfect day!

What are your typical hours?

9am–6pm. I never want my staff to stay longer than that. If we can’t get it done in that amount of time, we should just pick up again the next morning. I don’t believe in taking advantage of others’ schedules. I try to manage the jobs so that we never have unreasonable deadlines. I don’t think that’s fair to anybody.

How do you spend your evenings?

On personal projects and cooking. I like knowing who I’m buying my ingredients from, so I stop at the farmer’s market on the way to work, take everything with me to the studio, and bring it home at night. Cooking is the other way I love to express myself.

What music are you listening to right now?

In the studio, I really like to listen to soundtracks from Italian and French movies from the 40s, 50s, and 60s—I’m sure you’ve never had that response before.

Your favorite film?

I think it would be La Strada by Fellini. It’s a great one.

Do you have a favorite book?

It’s hard to only choose one because I have many favorites, but I do love a book called The Wine-Dark Sea by Leonardo Sciascia. It’s full of short stories that so concisely capture the essence of Sicily in a very beautiful book.

Favorite food?

I could never choose one. I will eat anything in Italy, unless it has dairy in it because I’m lactose intolerant.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I think it goes back to what I was saying before about role models. If I’ve been able to inspire one young female designer, I will be satisfied.

“At this point, my work and my life are totally, inextricably combined—you can’t separate one from the other and that’s just the way I like it.”