- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker December 18, 2012

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Matt Porterfield

- director

- filmmaker

- writer

Born in 1977, Matt Porterfield has written and directed three feature films, Hamilton (2006), Putty Hill (2011), and I Used To Be Darker (2013). He studied at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and teaches screenwriting, theory, and production at Johns Hopkins and Maryland Institute College of Art. His work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art and the Harvard Film Archive and has been screened around the world.

Interview

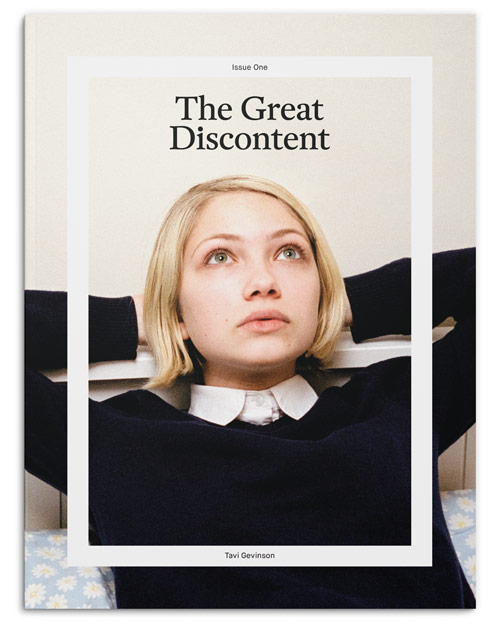

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Describe your path to becoming a director and filmmaker.

I was always really into visual and performing arts as a kid and throughout high school. I only applied to NYU because I wanted to get out of Baltimore and live in New York City so bad. Luckily, I got in, but had no clue what I wanted to do once I got there. I studied psychology for a year and my girlfriend at the time was in the film program. I saw what she was doing and became really excited to help her with projects and meet her friends. I transferred into the NYU film program and once I did that, I had access to the tools. Then I began trying to figure out the craft and how to be a visual storyteller. Film allowed me to combine all the things I like—fine arts, performing arts, and photography.

School wasn’t for me, though, so I dropped out and stayed in the city for a few years while I worked as a kindergarten teacher. After living life as a kindergarten teacher for three years, I found my way back to film and was hungry to make something. I applied to Cooper Union, but didn’t get in, so I decided to move back to Baltimore and write a script. I had been writing little scenes here and there throughout the years, but they were all set in Baltimore, not New York.

In 2002, I moved in with my dad and started writing the scenario for Hamilton, which we shot a year later. I had the help of one friend, a kid from Queens named Jordan Mintzer, who went on to produce that film as well as my second, Putty Hill. He signed on to help in any way he could or any way I needed him to. He helped with early drafts of the script, created a budget, and put together a shooting schedule—I didn’t know anything about that stuff, but he had production experience.

Did you meet Jordan in school?

Yeah. He was at NYU for one year, but then went to business school. In college, he did this cool series: he bought a wartime projector and rented prints from the Donnell Media Center and showed old films in his dorm room. He was showing all this stuff that seemed really visionary to me at the time because I had no previous exposure to the rich film history that he had experienced growing up in New York. He’s a real cinephile—now he writes for the Hollywood Reporter and publishes books about American auteurs like James Gray.

So, you returned to Baltimore?

Yes. My dad put me up and I got a job in a restaurant. I worked there for the next seven years, right through production and post-production for Hamilton, which took almost five years to make because I cut it all myself. After 18 shoot days, I had to take time off and raise more money. I stuck with it, but had to teach myself Final Cut Pro and all that shit. I never learned computer editing at NYU—we just learned on razors and tape when I was there. I hadn’t yet made that transition and had to figure it out for myself. It was important for me to go through every phase of production with it. It was a good learning experience, but I don’t think I’ll edit a feature again. I’ve learned the value of working with a really good editor on the last two films. So, Hamilton found its way into the world and then we started on another film called Metal Gods, which we couldn’t find financing for. That film became Putty Hill, which was very modestly budgeted, shot in 12 days, and was largely improvisational.

How did you fund your films?

For Hamilton, we were able to find a little private equity and I used money my grandmother had saved for my last year of college. I went to her after teaching kindergarten for three years and said, “I’m not going back to school, but I really want to make a film.” She was a nurse and worked for the state; my grandfather had two pensions, one from the city and one from the state. Combined, they had put enough together to help me with my last year of school. They gave me the money and that was the bulk of funding for Hamilton, along with the private equity. Plus, we did a fundraiser to pay for the sound mix.

We had even less money to work with going into Putty Hill—it was about $20,000 to shoot it, which we did in 12 days. Then we had to raise more money. We did a Kickstarter project for post-production so we could finish it and show it at the International Forum of New Cinema in Berlin.

Were you also working while shooting Putty Hill and your latest film, I Used To Be Darker?

When I moved back to Baltimore, I got this job at a friend’s restaurant and worked in the front of the house most of the time; sometimes I worked in the kitchen. That paid my bills for seven years. If I was shooting something or attending festivals, I could leave and come back—I always had a home there at The Chameleon.

Then, as I was finishing up Hamilton in 2005, this guy who is Head of Production at Johns Hopkins University—where I now teach—came in and expressed interest in what I was doing. His name is John Mann and we’d talk shop while I was serving him dinner. He asked to see the film and when I was finished, he was the first person I showed it to. He really responded and asked me to come and talk to his students. Then a class opened up and he offered it to me; one class became two, then four, and now I’ve been teaching at Johns Hopkins for five years, which is my livelihood.

“I have an egalitarian approach to film acting; I think anyone can do it. Not everyone can do it really well, but as a director, you should be able to communicate with your cast, feel empathy for them, and help them find the performance.”

Was creativity a part of your childhood?

From what I recall and from what my parents and siblings tell me, I had a really active imaginary life that involved games and role-playing and I also drew. All the way through elementary and into junior high, I drew all the time and filled books with sketches. I was also really into the natural world—David Attenborough was my hero—and I think that he somehow had an influence on my practice. His work was really observational and I think something about his relationship to the world mirrors my experience and was part of my formative visual language.

My parents both valued creativity and are creative people. My dad is a playwright and novelist and my mom teaches early childhood at a Montessori school—I think teaching kindergarten is one of the most creative jobs you can have. My parents gave me a lot of support and time to pursue whatever.

Did you have an “aha” moment when you thought that you could actually become a filmmaker?

I’m trying to think about when I really got it. I think it was maybe when I transferred into the film program at NYU and took this Intro to Film Production class where we shot on black and white film and cut it with razors and tape. I’m a tactile learner, so it wasn’t until I got my hands on the tools that it became actualized for me. I thought, “I really like this,” but it wasn’t until later that I realized it had the potential to combine all the things that interested me.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

My dad was probably my first mentor. He is a writer and taught drama and English for 45 years in Baltimore public schools before he retired. I learned a lot from him about discipline. Every morning before work, he woke at 3:30am, went into the basement, and sat typing on a Royal typewriter. Not only did I learn dedication and discipline from him, but he also has a gift for language. He’s a really incredible writer and I borrowed a lot from him in terms of style and crafting dialogue.

Along the way, I met Jordan Mintzer. Although we’re peers now, he was a mentor in that he exposed me to this world of cinema that I don’t think I would have found on my own or that I would not have found until much later. I certainly wasn’t finding it through the NYU curriculum.

Dan Carey, a producer who has officially come on board with I Used To Be Darker, has more industry experience than me and has been doing this for a while. He’s partners with Paul Giamatti, who he has produced a number of films for. Dan has lent me his ear and advice for the last eight years and I’m happy to be working with him regularly.

I’ve also been lucky enough to get to know John Waters over the last few years and he’s just full of good advice. He has incredible taste, is super prolific, and maintains a real grace and sense of humor about everything.

Tina: He’s also from Baltimore, right?

Yes, he is.

Were there any points in your life when you took a big risk to move forward?

Yeah, with Putty Hill. After Hamilton, I started writing my next script around 2006. It was called Metal Gods and it’s about a group of high school metal heads and a story of first love. I spent two years on the script, Jordan advised, and we started trying to find financing with the goal of shooting in the summer of 2008. Around that time, the economy crashed and we had already begun casting and choosing locations, but had no money in the bank. The risk was deciding to put that project aside and take some of the people we had found and craft something completely open and new. We had about a month to do that and we went into it not knowing if it would be a short or a full-length film—either way, we didn’t have a lot to lose. After some relative success with Hamilton, I was able to avoid getting hung up on that precious second project and instead, I pushed forward into something a little more unknown. That was a pivotal point in my career.

“I think that when you’re young, you can really break rules and do a lot with a little…there are so many people making films and finding exposure, even with limited resources…”

So, you had no script for Putty Hill?

It was just a treatment, a 5-page scenario. The locations were detailed in the script, we knew which characters would appear, and we had this fictional construct that bound everything together, which was the death of this young man from an overdose. Beyond that, there were no lines that were recorded or memorized; it was all collaborative work with the actors that was done on location.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Yeah, I’ve been lucky to have a real network of support. As I continue to try to make work, that network seems to grow. I’ve forged relationships with collaborators who I hope to continue to work with. Jeremy Saulnier is the cinematographer who has shot all three of my films and I’ve worked with the same editor, Marc Vives, on Putty Hill and Darker. It’s also nice to see more support from within the industry, which I think is important to sustain a career as a filmmaker.

Do you think your family was surprised that you went into film?

My grandmother would probably say no. She was the one who took a leap of faith and wrote me a check when I dropped out of school. I think my parents were a little more skeptical, but I’d be interested to hear what they would say. They probably would’ve guessed I’d be happier finding some kind of creative practice to build my life around.

You’ve been making films for about 12 years. What would you say to young people just starting out in the world of filmmaking?

First, follow your instincts—if you think you can trust them (laughing)—as opposed to listening to what everyone else has to say about your work and how you should try to pursue getting it made. There are certain industry standards that trickle down and dictate how filmmakers try to get stuff off the ground. I think that when you’re young, you can really break rules and do a lot with a little. Trust your instincts and that seed of an idea; hold it close for as long as you can. That will allow you to make a film for $200,000 or $2,000. If you’re close to the source material—the seed—then it should be flexible under any economical restraints. Maybe that’s a hard thing to learn for yourself, but there are so many people making films and finding exposure, even with limited resources—people who didn’t study film or go to film school or intern with a production company. They’re breaking the rules and making films for themselves. That’s what you can do when you’re younger and don’t have the responsibilities that come with age.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

That’s a good question. I do. I feel really lucky that I’m able to spend my time dreaming up ideas and spending months trying to get them made and seen. I don’t know how widely my work will ever be seen and if the films I make will change anyone’s lives. There’s an idealistic part of me that likes to imagine that, through film, maybe I can open people up to an experience outside of their own.

Over time, I’d like to figure out a way to empower people who are interested in the arts to make things for themselves. We do that a little bit as educators and teachers, but I haven’t figured out how to do that outside of the university system. I don’t know—if I made a lot of money, I’d give it away, but I haven’t had that opportunity yet.

Do you view teaching as a way of giving back?

Yes. I think I have a good symbiotic relationship with my students and we learn from one another. The work I do there allows me to put a roof over my head and feed myself and also affords me a lot of freedom to pursue my craft. I also work with a lot of my students on production and that’s a reciprocal relationship.

Do they ask you crazy questions?

Not enough.

What do you want them to ask?

I want them to be thinking about the ethical questions surrounding filmmaking, which I think about a lot. For example, how do we interact with other human beings and the wider world through our work, what responsibility do we have to our subjects and whatever reality we’re trying to depict, and what do we do when we have to break our own moral code or ethics to get stuff done? Those are things I want them to think about.

I’m also teaching a class on how to direct actors for film and that gets into some interesting territory because there are no rules. I have an egalitarian approach to film acting; I think anyone can do it. Not everyone can do it really well, but as a director, you should be able to communicate with your cast, feel empathy for them, and help them find the performance. In my experiences, I’ve found that a lot of film students don’t have the confidence or empathy needed to work with actors.

Are you satisfied creatively?

Yes, I am. This year is the first I’ve felt creatively satisfied. Hopefully I’ll feel the same in 2013.

Why do you feel satisfied?

I feel like I’ve achieved a balance between my personal and professional life, and my creative life influences both and is the real anchor. I now have confidence as an artist—in my practice, my work habits, and my ideas. I’m gaining that through experience and by building a group of people around me who also have confidence in me.

There have been a couple pivotal things this past year: being included in the Whitney Biennial, having my first two films picked up for the permanent collections at MoMA and the Harvard films archives, and Darker getting into Sundance. Even more than those things, it’s how I spent my hours; the percentages are right and I don’t want for anything.

Is there anything you’d like to do in 5 to 10 years that you’re not doing now?

I’d really like to direct an original script that someone else wrote or adapt a work of literature or an existing film. I’d like to experience working with more established talent—actors who are more experienced and recognizable. Making a film in another city or country would be a cool challenge. Directing something for the theatre is something I would like to do.

You have no shortage of things you want to do.

They all pretty much involve film. I’m not going to write a book, that’s for sure, and as much as I love music, I’m not going to be in a band. You stick to what you know—that’s my secret. I write about what I know. It’s close to home.

That leads right into the next question. How does where you live impact your creativity? All your work is deeply embedded in your hometown of Baltimore.

I think the local has the potential to be universal. As a young artist, it’s important to write about what you know. I love Baltimore. It’s a super rich culture with a lot of diversity and conflict. There are a lot of things that inspire me: the geography and seasons, its proximity to the water, the maritime traditions, and the post-industrial economy. I like cities where people are struggling to assert their identity, which seems so tied to culture and commerce in the United States. I feel like in New York anything is possible, but only if you have the money; in Baltimore, it still seems possible to do a lot with a little.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

It is. I feel a lot more inspired by the creative community at home than in the larger filmmaking community in the US. I try to travel in circles and I’m happy to have a really cool network of artists, musicians, designers, academics, and builders of various things that I can tap into in Baltimore and in doing so, skirt the regional and NY film industry. I also get to travel and connect with filmmakers in international scenes, which is cool. It’s neat that it can happen that way.

What does a typical day look like for you?

They’ve gotten atypical lately. I’ve been in New York for at least four days a week the last two months, so travel has become part of my routine. If I’m at home, I like to get up around 8:30–9am, fix myself coffee with an AeroPress, get some granola, go into the office, and get more coffee. I try to work in there for an hour before anyone else is around. It’s great to begin the day getting correspondence out of the way and then open up to other things, whether it’s putting press materials together or meeting with students or planning curriculum. I feel like I hit my stride on the more important stuff around 11am.

A day in the office doesn’t involve any creative writing. Those days are very different. Scheduled writing and script development requires total attention and devotion. I spent all summer in Montreal and I’d get up at my normal time, but then go to a cafe and work for eight hours straight. That’s it for the day, but the computer shouldn’t be open and I can’t be emailing.

Do you write everything out by hand?

I fill notebooks. For months, I’ll fill notebooks until I feel like I have enough structure in place where I can transcribe it with some word processing software. Sometimes I’ll take it into Final Draft, which is screenwriting software, but usually I’ll just do it in Word, make the treatment, go through several drafts of that, and then take it into screenplay format. But when I’m first writing, I do it longhand, fill up books, and try not to ask too many questions.

What happens if you get stuck?

I just sit there. This goes back to one of the things my dad taught me. Even if you don’t have any ideas for the day, you have to stick to the block of scheduled time and sit in front of the blank page. Even if you’re sitting there for two hours and nothing happens, stay there because, all of a sudden, an idea might come.

I think it can be hard to know when to take a step back and say something is finished. I lived with a Romanian artist for a couple years and he was a painter. I had to walk through his studio to get to my bedroom and every day when I came home from work, the painting he was working on would be completely different than what it was the previous day. He was working on a series based on homes from his childhood neighborhood and every day he was done; he had found what he was looking for until the next day came around. Finishing can be really challenging.

Do you have a current album on repeat?

This 3-disc Bruce Springsteen Live from the Roxy album from 1978.

Do you have a favorite movie?

That’s hard to answer, but I have to say the documentary, Streetwise. I feel like the characters are captured in time—some of them have been lost to history, some are living very different lives, and some are dead. There’s this thing that André Bazin, a famous French film theorist, says about film and photography—they embalm time. That’s one of the things I like about that film in particular.

My favorite movie that I’ve seen recently is Leviathan. It premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival and also played at the New York Film Festival. It’s going to be released in March or April by The Cinema Guild, who put out Putty Hill.

Are you into any TV shows?

I love The Wire and I’m digging Game of Thrones right now. I don’t have a TV, so I catch stuff online.

What about a favorite book?

Ryu Murakami’s Almost Transparent Blue, which I keep going back to and just reread. I pulled some chapters from it for my students to adapt and film. Also, Ann Carson’s verse novels are close to my heart. And there’s this book of short stories by Cookie Mueller, who was an incredible writer in her own right, even though she doesn’t have a lot of published work.

Favorite food?

French fries.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I’m really interested in creating a body of work that reflects the diversity of the American middle class. I’d like to make a number of nuanced films that provide a window or document situated in our present, but with a humanity and universality that can transcend—that’s it. And maybe if I ever make any money, I can have an estate to pass on to my children and grandchildren to execute.

“Even if you don’t have any ideas for the day, you have to stick to the block of scheduled time and sit in front of the blank page. Even if you’re sitting there for two hours and nothing happens, stay there because, all of a sudden, an idea might come.”