Join us for Deconstructing Discontent, a multi-day workshop at Taliesin, focused on exploring professional challenges and opportunities for transformation. Reach out for more information.

I’d love to start out just by asking what you’re excited to talk about today. What bubbles up as something that’s exciting and possibility-filled for you?

I have been thinking about how excited I am to talk about my art and my existence in the world in a space that amplifies creatives, knowing that for me, at least, prioritizing creativity is such a must. This feels like an amazing opportunity to connect and put some of my—I’m gonna call it “heart vomit” out there. [laughs] I haven’t found a better term for it yet. I’m excited to continue to clarify the shit that’s exciting to me.

Both exciting and, I expect, a little vulnerable.

Oh yeah. I mean, the edge between the excitement and the vulnerability and the anxiety is so, so fine, right? I remember I was giving a photography presentation in college in Rome, and I burst into tears during my presentation. And I realized that when I’m talking about something that is truly vulnerable and from the deepest part of me, yeah it’s fucking terrifying and it can be extremely emotional. But on the other side of that edge is just as much excitement.

So, why don’t you tell me about what it is to be Sheyam in the world. Tell me what your existence looks like?

My name is Sheyam, and my pronouns are “she” and “they” currently. I was born in Cairo in 1976 and when I was five months old my parents emigrated to the States. Since then, I’ve lived all over the place. It’s been a really huge part of who I am—the languages that I speak, the locations that I’ve found myself in, the opportunities that I’ve had, the different people that I’ve met, and the different fingers that I have in different communities across the world. It gives me a framework that I’m really grateful for.

I exist now in the world as a queer Arab abolitionist. I believe that true liberation for everybody, starting from Palestine, can happen within our lifetime. And I think it all starts with every single one of us. So, what it feels like to live my existence is to try to remind myself everyday through my art, through how I walk through the world, that the reason we’re here and the purpose that we all have is just true and free expression.

After coming to the U.S., my understanding is through your dad’s role with the UN, and your own travels, you were in Cairo, in the Sudan, Zimbabwe, later Germany, back to Cairo, Charlottesville in Virginia—all over the place. As someone who’s lived kind of in between, how did that influence your understanding of self and ultimately of what it means to be an artist?

That’s the crux. What I understand to be my path now, which is living and creating from the purity and truth of myself, is the antidote to everything that I felt growing up, that was other and marginalized. As a child, I never quite felt in the right place or belonging to the right culture. I would go to Egypt and people thought I was too American. I would be in the States and I never really felt like an American kid. It took me until very recently to figure out that I could just exist in myself, in all of the things that I am, because I didn’t actually think that I could be all of the things that I am, which is a brown, queer person living in this country, my partner is trans—all of it. It informs everything about me. So, I can’t really pick it apart from my art or my personhood or definitely not my politics. [laughs]

Right. And it seems like that integration—when you talk about the responsibility of humans being that true and free expression—to pull it apart would do a disservice both to self and to art?

But if you think about it, that’s what we’re taught and told to do our whole lives. Everything in our lives currently is conspiring to not allow us to live our free expression. Everybody is living that truth. Everything we see, everything we have to go through day to day, the jobs that we go to, the bills that we pay, the responsibilities that we have, never having the time and the resources to yourself to even figure out who you are, is purposeful and harmful—incredibly harmful. So that is what is so important, right? Somehow trying to claw that time and space for yourself. To be able to connect in yourself to then connect to the universe and community and all of us. And then we all move forward into, you know, the rainbows. [laughs]

I feel like you’re the kind of person who just emerged into the world fully understanding all of that, but I know it’s been a heck of a journey. Can you talk a little bit about that process of reintegrating yourself—your queerness, being Egyptian—but also then returning to art, returning to creation?

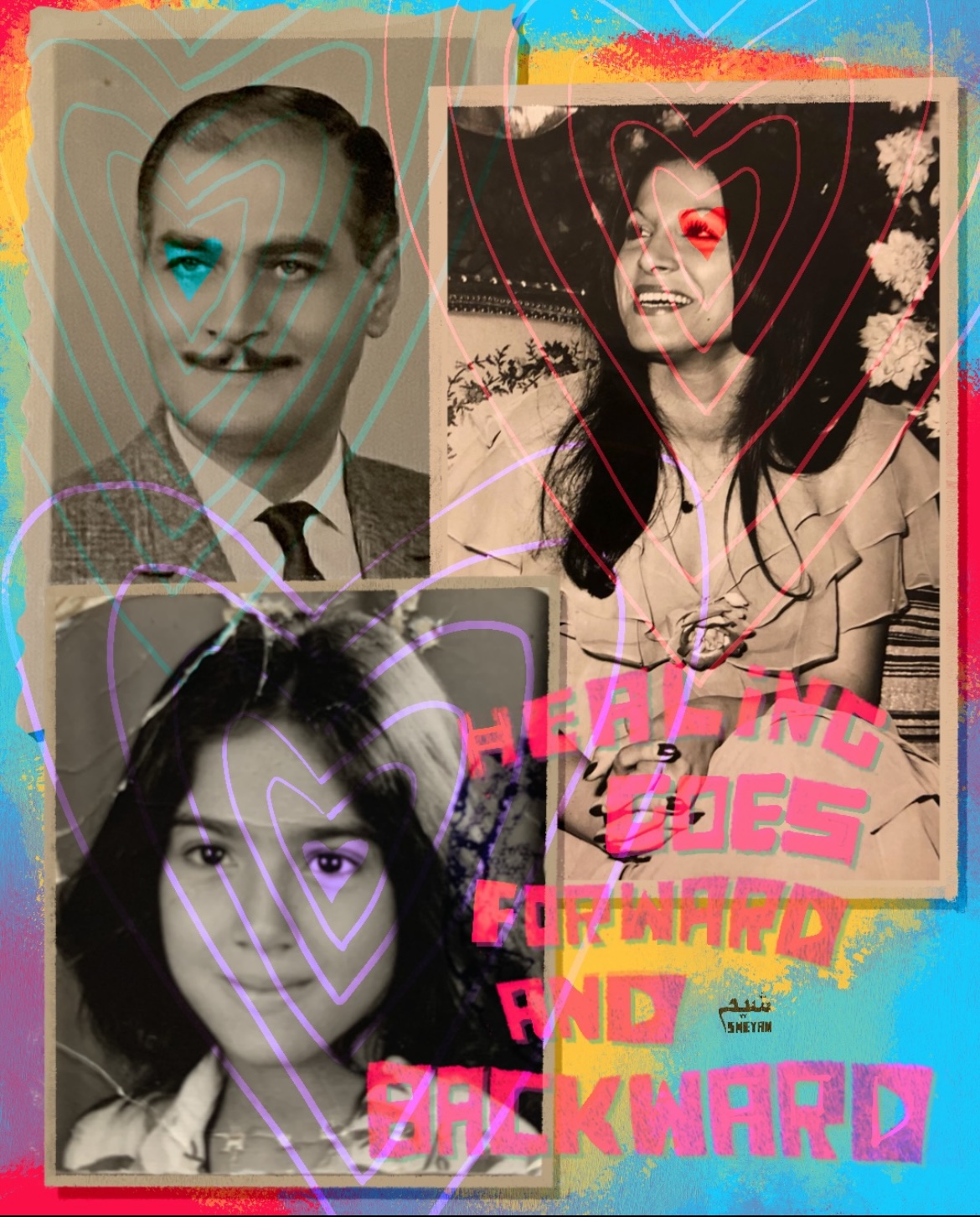

So, growing up, kind of between worlds, with these parts of myself that were hidden for so long. . . what it feels like to me now in hindsight is my parents are incredible people, who bucked tradition in their own ways. They were some of the only people from their families who came to the States. And they were responding to all of the pressures and all of the generational trauma that they inherited. At the time it felt like an incredibly dysfunctional family, and it was hard for me to find a way to be in it. What I understand now is that I think I was being this magical little child. And my parents probably freaked the fuck out. They were probably like, “She’s so sensitive. This kid, we need to toughen them up.” [laughs] I understand now that they were really trying to protect me from the evils of the world.

What it felt like at the time was having to hide so many parts of myself that were very emotional, and very empathetic, and very sensitive. So, what I did for a very long time was follow the rules really, really reluctantly. I did all the things that I was supposed to do, but I was drowning while I did them.

When I got to college at 17, I was so conflicted about so many things. I went to Charlottesville, Virginia, and I was faced with a lot of things—the privilege that was in my face, and the whiteness and all of it. At the same time, I was realizing that I didn’t necessarily hold the same values as the places that I came from. And I didn’t know where I was going, ‘cause the new place I was in, wasn’t where I needed to be either. I dropped out of college and ended up back in Rome doing a year abroad. And that was more artistic, but I was living back with my family, and that was not quite the place that I needed to be at the time. Therapy was one of the tools that eventually started to help.

After that, I ended up moving to New York, trying to follow my own path—this might be the vulnerable part [laughs]. What happened was, my parents felt that I was lacking direction, and they bought me a ticket back to Rome to live with them. And it was one of the two times in my life when I had a panic attack. I was like, “Oh shit, I can’t—that can’t happen.” I overdosed that night, and ended up in Woodhull Hospital in Brooklyn. My dad flew to pick me up and I went and lived with them, and nobody in my family ever talked about it. [laughs] So, what happened next was over a decade of clawing my way back to self. And what that looked like was eventually figuring out that I had to get back to my creative side, because all of those years, I wasn’t accessing that part of me in the ways that are healing and in the ways that connect you to love, universe, other people.

I ended up being a journalist for several news agencies. The last reporting job I had was for Bloomberg News. I hit a point like, “I gotta go.” My mom didn’t talk to me for three months after I quit Bloomberg, because she was like, “Well, this was prestigious.” I was covering economy and politics, I was traveling everywhere, I had an expense account and was covering events with heads of state, something that parents and neighbors love to talk about. [laughs] But when I thought about it, I was like, “I love the writing, the deadlines, all the languages that I can use. I love to travel. But making more money for really rich people who are ruining the world is not how I wanna keep living.” That was 15 years ago.

So, characterize your current day to day and juxtapose it against where you were then.

Oof, I would say I’m a different person, except I know that person’s still in there. But the outlook is so different—the hope that I have. It was hard to exist in the world, you know? I didn’t see a path forward, and now I do. Now I fucking do, because the people who inspire me are the people who are out there also seeing a better way forward, who agree that none of us have to accept the status quo. And, yeah, 15 years—a lot has happened. [laughs]

Now you’re in Portland. You’re living a life centered on wellness and joy and creating. Talk a little bit about what art and practice looks like for you today.

A few years ago, my partner and I were living in New York. I had just finished season two of Ramy, and I was getting back to myself. I did this little exercise where I was like, “What do I want? What do I actually want my days to look like?” And when I wrote this list out, it was so far removed from what my day to day actually looked like, I understood I was gonna have to make some changes. That culminated two years ago, with Emmett [Jack Lundberg] and I moving to Portland, (Multnomah and Clackamas) in Oregon. It was exactly what I needed in the grand scheme of things—personal healing, familial healing, a change of scenery. Living in Portland now is a total 180 from lives I have lived in the past.

So what I do is a bunch of practices. I have a pretty solid mindfulness and meditation practice that is crucial for figuring out who you are or what you even think—what you like, what you don’t like, what you stand up for, what you believe, what you are gonna fight for, what we’re all fighting for. I also take a daily morning walk, wherever I am. Usually it’s around Portland, and it is one of the greatest joys of my life—walking in the morning with music, moving my body and being in nature. We live really close to a volcano and it’s forest-y, trees everywhere, with flowers and colors that have affected the way that I see everything. It connects me to a gratitude that is so great. That sets my day.

While I’m on my walks, I usually figure out my day, whether I’m doing client work or production work, or my personal work, which is whatever the hell I feel like doing that day. Currently, it’s teaching myself to sew and quilt, and do patchwork, and make doggy clothes for our friends’ pets. [laughs] Earlier this year I taught myself stained glass, and I found neon paints and acrylics and watercolors again. I mostly spend my day trying to foster and nurture the flow of creativity, whatever it feels like in the moment. My partner and I both work from home and have a lot of creative overlap, but we also spend entire days apart, just doing our own thing. And that, I think, is pretty crucial. [laughs]

One of the things that I’ve heard you share in other conversations, is the critical and relatively recent discovery of community through queerness, and specifically a sense of your own Arab queerness. One of your earliest projects I saw was the Queer in Arabic t-shirts. Can you talk a little bit about that project?

Totally. In the summer of 2020, the start of Ramadan was coming up, which everyone observes in their own way. For me, it’s always an opportunity to look inward and figure out what I can do for others. That summer, an advocate and activist, Sarah Hegazi, took her life after being imprisoned and tortured by Egyptian police for having raised a rainbow flag at a concert in Cairo. It struck such a chord in me, when I realized we’re all the same. It could’ve been me. It could’ve been any of the people that I know. But for the grace of God, but for the grace of Allah, it happened to not be. And when I thought about how many of our people are persecuted just trying to live their own truth, something in me kind of snapped, or changed. So much of the shame that I was carrying within my family, within my culture, within my community, didn’t have the same hold on me anymore. I was like, I need to be the person that I needed as a child.

As a writer, I’m fascinated with language and etymology. The only words for queerness in Arabic have terribly negative connotations and haven’t necessarily been reclaimed as something that I would wanna identify myself as. Queer in Arabic, the design that I created, is a transliteration with Arabic letters that read Queer, the word. I launched it as a fundraiser raising money for Muslim queer and trans youth. I realized, that’s who I’m here for. For the queer and trans youth who are the future, who are the diversity in nature and in the world that we all need.

You were at a point, when you had a plane ticket back to Rome from your parents, of such separation from self. And now, not to say that you’re at the other end of the tunnel, but you’ve found a place of directionality toward wellness and toward wholeness. Whether it’s to your younger self or to those youth that don’t see a path forward, where does hopefulness come from at the beginning of the journey? I don’t wanna ask you to give advice, but I guess I’m asking you what’s the advice?

[The hopefulness] is inside you. It was inside me. It can’t really come from anyone else. And that’s the hard part, right? Because we have people—I had people that I wish that I could help. I wish I could do these things for you. I wish I could give you the advice. I wish I could, but sometimes all I can do is support and just be there, and we all make our own choices. This sounds so fucking cheesy [laughs], but every single one of us is the magic. The magic is you. The answers are inside you. Truly the only way to connect to self is to connect to self. The only way to connect to everybody else is to connect within myself. And it’s the only way that I could start to make choices that were in my own best interest, which is what is then in the best interest of my community. The best interest of my community is for me to show up as my fullest, wholest, healthiest self and that means not hiding. Severe depression, severe anxiety are things that I grew up with, and depression and anxiety are correct responses for us to be having right now.

Truthfully I don’t think there’s anything wrong with our mental health. I think it’s the world that’s so fucked up, right? Like why wouldn’t a teenager living in Virginia, who has their entire government coming down on them to not be able to use the fucking bathroom at their school, why would that kid not be like, “The world is against me, and I can’t really live here?” What I’m trying to say is, your depression and your anxiety, and your difficulties are totally understandable. And the answer is to actually go into that and figure out how you can make the tiniest changes. It is really the tiniest changes. It’s changing what I can see in front of my eyes everyday, like my fingernails. And it’s framing and reframing your world closer to what you think it could be like.

“It is really the tiniest changes. It’s changing what I can see in front of my eyes everyday, like my fingernails. And it’s framing and reframing your world closer to what you think it could be like.”

Like some days it’s just about the walk. Some days the walk is enough. Some days getting up and eating, and taking care of your hygiene, it’s enough. But it’s that step and it’s that choice.

Absolutely. Sometimes it’s just about the walk. Sometimes, if you just sat with your new cat that you rescued and all you’ve done is connect with a creature and make them feel safe and loved, you have changed the world already. Sometimes it’s just about losing yourself in the tiniest details of something maybe nobody else will see, but in the time that you were doing that thing, there’s nothing but pure you and universe there.

Someone who’s in an in-house creative role, or a corporate space, or in entertainment or production, may feel like the type of creativity you’ve described—that kind of “start the day with a walk, meditate, follow the creative flow”—is the most impossible reality. [laughs] As someone who has worked all-consuming jobs in the entertainment industry and in production, and continues to experience periods of production and intense, deadline-driven focus, how have you navigated that tension?

So much of me and my choices and what I’m doing now are almost a reaction to production work, especially in the entertainment industry. After I left Bloomberg and Rome, I went back to New York and started working as a PA in film and TV. I worked my way to doing graphics and art for film and television, which I’ve been doing for the last 15 or so years. Some of the pieces in media that I’ve worked on have been pretty well known, and I’ve done a lot of props, pieces of set dressings, sets that I am incredibly proud of. What it feels like nowadays, and what it has kind of always felt like, is that there are a lot of incredibly creative people who are basically giving their lives to the industry, an industry whose bottom line is just the money.

In my experience, working five to six months on a job, I come out of it like a shell of myself, having to catch up on literally every single life admin piece that I have ignored for years at this point—medical, health, not having a life, crazy sleep hours. The amount of responsibilities given to people in the industry, minus the support, turns into way too much stress for people to be dealing with. So I have been trying to work less. What I have been doing for the past several years is sort of six months on, six months off. And part of us moving to the West Coast was also a reallocation of resources, of not having to work every single day of my existence like I did in New York just to pay the bills. I wanted time and space. I knew that that was exactly what I needed to reconnect to my creativity.

The more I focused on my own creativity, the more I’m able to reframe and redefine what success means, and what the financial burdens are too. It’s about reprioritizing. I care less about the things that I used to care more about back then. I’m no longer trying to be a “success,” or get rich in any of those ways that I was taught to chase. My day is focused on gratitude and smoking weed and sometimes eating mushrooms, and diving into my creativity because I know that that’s how I can then synthesize my experience, alchemize the shit I’ve gone through, and then bring it back to my community, and be like, “Ooh, look at all this gold.” [laughs]

We’ve talked about the walk as a place of inspiration, and about following that internal sense of creativity. Are there people who have become critical to that creative process? Whether they’re collaborators, or inspirations, or members of the community that you turn to when you think about your art, your work?

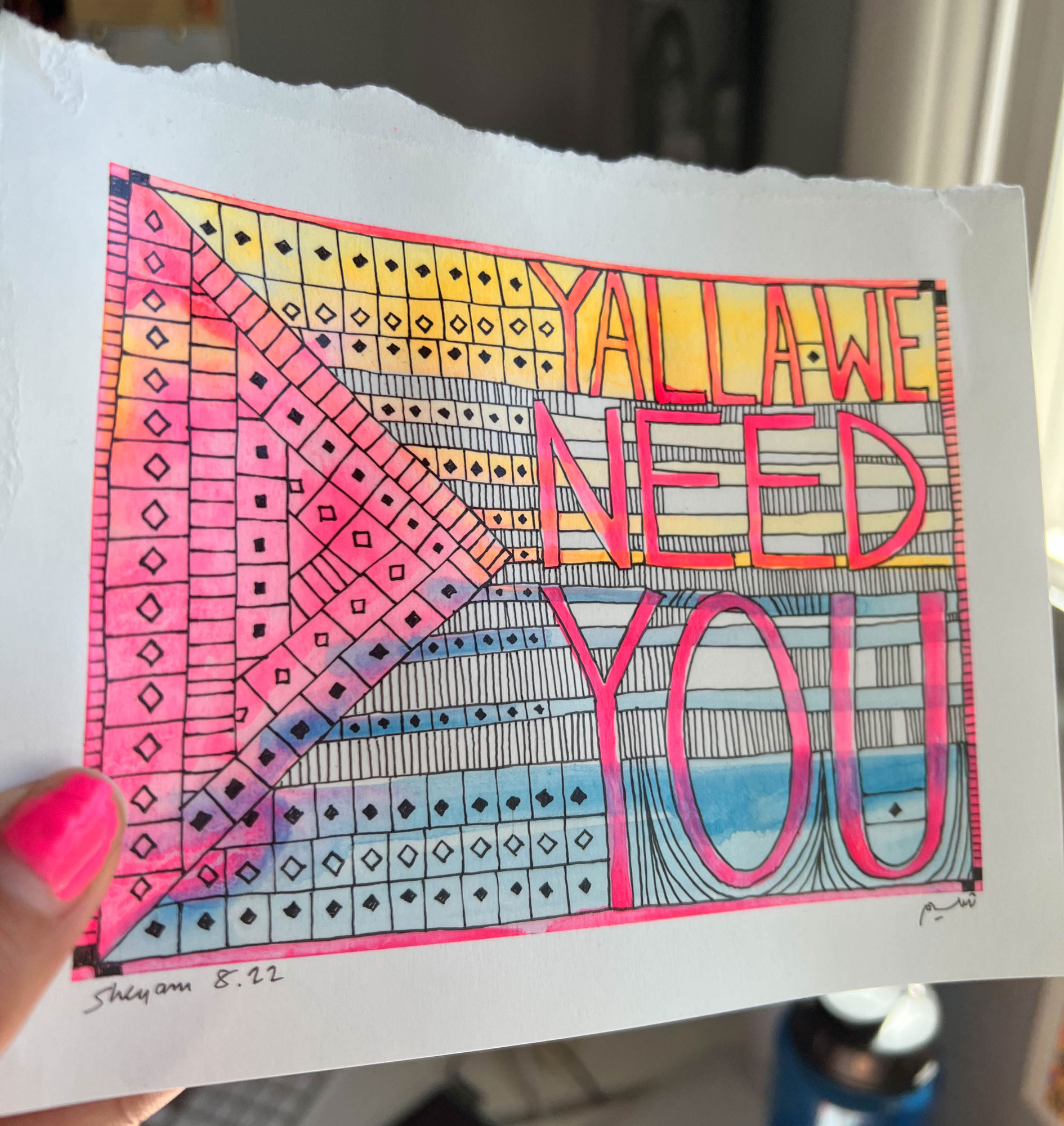

The first people who come to mind are people who are putting themselves on the line with their art, with their body, with their expression, in Egypt, Lebanon, and Palestine. In places where it’s a lot harder to carve out a relatively safe existence together the way that my partner and I have done. People who are fighting the good fight are the people that always give me so much fucking hope. My partner, he’s also my creative partner in so much. We made a TV show together. He wrote a new script and I am producing it with him. And he’s the person I turn to for everything. And the people in my community. I just thought of the advice I would give to people struggling to find a path forward.

Did you? Tell me.

“Yalla we need you.” I just wanna tell anyone, if I were to tell myself back then, I would be like, “You need to get your shit together. Figure out who you are. We need you. Like, we need you. Specifically you.” That’s all. [laughs]