- Interview by Tina Essmaker January 14, 2014

- Photo by Chris Herwig

Alastair Humphreys

- adventurer

- filmmaker

- writer

Alastair Humphreys is a British adventurer, author, and blogger, who has been on expeditions around the world. More recently, he has walked across Southern India, rowed across the Atlantic Ocean, run six marathons through the Sahara, and completed a crossing of Iceland. The author of five books, Alastair has pioneered the idea of microadventures and was named as one of National Geographic’s Adventurers of the year in 2012.

Interview

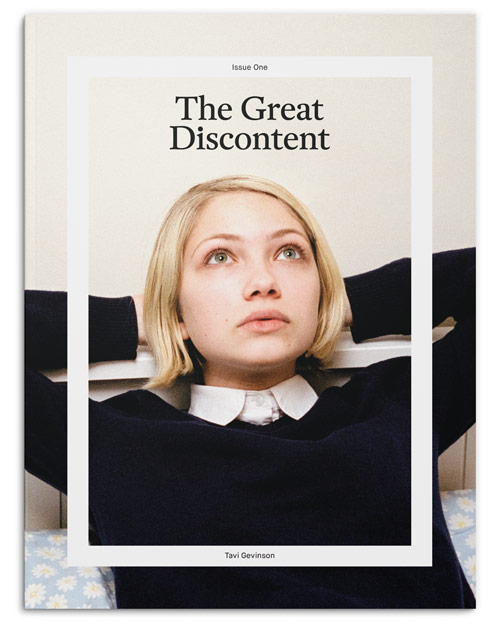

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Describe the path to what you’re doing now.

I guess my path began when I finished high school and went to live and teach in a little village in South Africa. That got me really excited about traveling to far off places.

After spending a year in Africa, I returned to Britain to attend university and study zoology. That was when I started to become interested in physical challenges and pushing my body. I also started reading a lot of great travel and adventure literature. Those three things—wanting to travel the world, wanting to do so in a difficult and slightly masochistic way, and being introduced to a great heritage of adventure literature—not only inspired me to start going on trips, but to start writing as well.

Zoology was a bit of a silly choice as I was not very interested in it, but I earned my undergrad degree and then post-grad, I went on to earn a degree to become a high school science teacher. Immediately after graduation, I realized that being a teacher was too much like hard work, and the much easier option was to jump on my bike and cycle around the world. (laughing) So for the next 4 years, I cycled 46,000 miles through 60 countries.

Wow! How were you able to do that?

Since I had started at university, I knew I wanted to do something big after, even though I didn’t know what that would be. I got a couple of jobs and started living cheap to save up money. By the time I set off cycling, I had saved up about £7,000, which amounted to about $10,000 at the time. It didn’t sound like enough money to get me all the way around the world for four years, but I figured that if I were to get a proper graduate job, then there was a big chance that real life would get in the way of going on the trip. I would likely get a wife, a cat, and a mortgage, and before I knew it, I’d be 50 years old and wishing I had done more when I was in my 20s. For me, the better option was to leave with the small amount of money I had, live cheaply, and just try to make it happen.

I didn’t have any sponsors or anything, but it was very simple. It was me, a bicycle, a tent, and a sleeping bag. There are millions of people who own that stuff; if you own those things and are fit enough to cycle a few hours a day, then you can make it around the world. You just repeat a single day’s ride over and over again, for however long it takes, until you arrive back where you started.

What happened after you came back from the cycling trip?

After I came home, I wanted to write a book for personal reasons: it was a mental challenge to follow the physical one. In order to pay for things while I was settling back into my life in Britain and writing my book, I started to give talks about my adventures. I spoke in schools or anywhere that would have me. At first, I spoke for free, but as I got references, I was able to start charging a little bit; the more references I got, the more I could charge. I gradually spoke more and increased my rates until talking just about paid for living expenses. And that was the moment when I realized that perhaps I could make adventuring a career. Since then, it has become a cycle: when I come back from a trip, I’ll write a book, make a film, or give talks until I’ve got enough money and wanderlust to go on the next adventure.

What was the most recent trip you took?

My latest trip was walking through the Empty Quarter Desert in Arabia almost a year ago—I got home just in time for Christmas. I’ve spent the last year turning that expedition into a film.

“This began because I wanted to do what I loved, which was going on adventures. If you do what you love and are willing to work hard at it and be innovative and imaginative, then it’s likely that you can somehow turn it into a living.”

Did you have a particularly creative or adventurous childhood?

I liked the outdoors in the same way that most boys who grow up in the countryside like it. I climbed trees and rode my bike, but I wasn’t particularly adventurous or tough. I didn’t get into adventuring until after I left high school.

In terms of being creative, it’s important to have a diverse set of skills in order to make a living from adventures. As a kid, I loved reading books, and if you read enough books, then you get into a position of being able to write books, which I’ve done. Later, I became interested in photography when I realized that having lovely pictures to accompany the talks I gave would help my adventuring career. I took a photography course and focused on improving my photography until the invention of the DSLR, specifically the Canon 5D Mark II, which did HD video as well as photos. As soon as that camera came out, I decided that it was a chance to teach myself how to make films as well. I had never been interested in filming my stories because it seemed obtrusive to the experience: the journey has always been the primary thing. However, since the DSLR camera was part of the kit I would be taking with me anyway, it seemed like a chance to jump to the front of a new trend rather than just tagging along behind it. That camera was the most expensive thing I had ever bought in my life, and it seemed far too expensive to be taking down rivers and banging on the side of mountains, but it was worth it. I’ve come to love the video, and it really adds to my storytelling.

Did you have an “aha” moment when you knew this was what you wanted to do?

No, not really. It’s been a very gradual, non-strategic thing. This began because I wanted to do what I loved, which was going on adventures. If you do what you love and are willing to work hard at it and be innovative and imaginative, then it’s likely that you can somehow turn it into a living. There has been no master plan to it, really: it was me trying to work out a way to pay for what I wanted to do.

A really nice spin-off from adventuring has been growing to love the process of writing books, making films, blogging, and the whole storytelling side of life. I still love the adventures themselves, but I would never have gotten into the creative side in a normal run of life.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

I don’t have any specific mentors, but the adventure community is quite cooperative and helpful. There are various adventurers who I now consider to be good friends, and I go to them for their opinions. When I try and write a blog post or a book, it’s like those people are there in the back of my mind, judging me; it’s a reminder for me to keep the quality high. My natural inclination in life is to be quite hasty and slapdash—I tend to rush, rush, rush through things—so it’s good for me to be reminded to slow down and make things better.

Has there been a point when you’ve decided to take a big risk to move forward?

The biggest risk I’ve taken, outside of the risks of expeditions, was changing the direction of my adventures pretty dramatically. The traditional model is to go and do really epic, heroic, and manly stuff, then come home to write really epic, heroic, manly stuff. That’s the way it tends to work: it’s a vicarious experience that normal people can’t have, and that’s why it’s appealing. After doing so many talks and speaking to so many audiences, I’ve realized that virtually everyone likes adventure. Even people who are not actually going to go on an adventure are still quite interested in hearing about them.

But I wanted to break down the elitism, the barriers, and the excuses—real or perceived—that stop people from going on adventures, so I came up with the idea of microadventures: deliberately small, almost provocatively mundane adventures. Generally, the excuses are things like not having enough money or time, not living somewhere geographically wild or exciting, not having the right equipment, or not being fit enough. However, microadventures are close to home and can be done on the weekend or even midweek. You could leave work at five o’clock, take a train out of town, go sleep on a hill, and catch the train and be back at your desk by nine o’clock the next morning. In that brief little space, you’ve had a proper adventure: you’ve gained wilderness experience, you’ve done something you’ve never done before, and you’ve challenged yourself.

When I first started doing microadventures, I was worried because they’re not the adventures that are traditionally done by “professional” adventurers. However, to my surprise and relief, they’ve become far more popular than any of the big trips I’ve done. That has dramatically changed the direction of my career.

“I wanted to break down the elitism, the barriers, and the excuses—real or perceived—that stop people from going on adventures, so I came up with the idea of microadventures: deliberately small, almost provocatively mundane adventures.”

Like many people, I can’t afford to take a whole month off, but I could take a long weekend or even a night. That sounds like fun!

You should do it. I actually received an email from a man in New York city who did his own microadventure last summer. That has been the greatest thing: since I have started blogging about this stuff, normal people with normal jobs are going off and having adventures, too. And it’s happening all over the world.

That’s great! So, are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

I think so. On the one hand, my job is very simple. It’s not like I do something that is difficult for my friends and family to understand. My mom and dad are very happy that it has become a viable, sustainable career for me, and they are really supportive. I do think that what is difficult for them—and this is probably true of anyone who’s totally obsessed with what they do—is that my family finds it hard to accept how addicted I am to the adventures and storytelling, and how hard it is for me to switch it off.

What did they say when you first told them you were going to cycle around the world for four years?

In the beginning, my parents had a lot of doubts about whether or not I’d actually make it all the way around the world. Personally, I had a lot of doubts as well. After the bike trip, there was a lot of skepticism about me turning adventuring into a career. I think they thought, “You’ve had your fun, now grow up and get a proper job.” It took a while for my parents to accept this as my career.

Have you ever been scared on trips, especially that first one?

I’m not very brave. I’m not an adrenaline junkie or a daredevil: I’m a very, very normal person who gets scared of normal stuff. The thing about risk is that if you manage it carefully, and you stay on the right side of risk—rather than recklessness—then it’s quite exciting to see your skills put to the test. I think that can become quite addictive.

I do get scared sometimes, but, generally, the things I do are not exceedingly dangerous. Of course, I could get run over while riding my bicycle; or when I went across the Atlantic, I could have gotten washed out of the boat by an enormous wave. There are things that you can do to minimize the risks, though, and I think that so long as you are sensible then they’re risks worth taking.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

That’s a great question. For a long time, I’ve been well aware that while the adventuring I do is worthwhile and fulfilling to me, it has zero contribution to society.

Writing books helps a bit, because putting something good out into the world is a useful thing. After reading one of my books, people often email me to say it inspired them to do X, Y, or Z with their life, and I find that rewarding. Also, since I started writing about microadventures, I get regular emails from people who have had their lives impacted by that in a small, but very significant way. That’s a big motivation to keep doing what I’m doing.

Are you satisfied, creatively or otherwise?

No! I’m enormously dissatisfied: I’ve got the restless wanderer’s curse. (laughing) It’s like opening Pandora’s box. Of all the things I will be in life, I will never be satisfied.

That being said, what are the things that you’re interested in doing in the next few years, perhaps things that you haven’t done yet?

There are two things I would like to do. One is to go on another big and difficult expedition; I’d like to scratch that itch. I loved making my first film, Into the Empty Quarter, but I’ve learned so much. Now, I want to go out and try to make a better film.

The second thing I’d like to do at some point is write a very good book. I’ve written six books now, but I want to write a very, very good one. I don’t know how I’d define that, but I feel compelled to do it.

“I’m not very brave. I’m not an adrenaline junkie or a daredevil: I’m a very, very normal person who gets scared of normal stuff.”

If you could give advice to a young person starting out, what would you say?

My advice would be to find something that you really love doing, something that you’re passionate about, and begin doing it. Learn to do it very, very well. Only once you’re good at it and have started to build up a bit of a repertoire should you begin trying to work out how to make it pay. You can make virtually anything your passion if you begin it: that’s the hardest thing. I get lots of emails from people who want to be full-time adventurers like me, and my advice to them is always, “Go do something really epic because you want to do it. Only after that can you worry about turning it into a job.”

Yes. You can’t make a living from something until you’re actually doing it first.

Exactly. Trying to monetize everything makes you less able to take the crazy, stupid, reckless risks that are necessary. It’s like what you did with The Great Discontent: if you do something you love and make a really beautiful and quality product, then the rest will follow.

Agreed. Are you living in London right now?

I live just outside of London.

How does living there impact what you do?

I essentially live in the hub of Britain, and that has been great in terms of getting to know interesting people who do really good stuff, whether that’s adventuring, writing, or photography.

Living here has also been instrumental to the microadventure idea. When I’m in the UK doing things to pay for my next adventure, I’m actually living somewhere that isn’t very nice, and certainly not very wild. The idea of nipping a few miles away from home or jumping on a train and climbing a hill for the night has had a real impact on me. I’m now living the same life as all the people who can’t have big adventures because they don’t live somewhere beautiful: it’s the same for me, but I still go and find adventures.

Is it important to you to be part of a community of other adventurers?

It’s a bit of both. I did the Empty Quarter trip with another guy, and the trips themselves are quite often collaborative expeditions. This film was the first time I’ve collaborated creatively, and I really enjoyed that process. The thing I miss about being a solitary, self-employed creative person is not having a good team to work with. The flip side of that is that when you work by yourself, you can work harder and longer than everyone else, and you can be a ludicrous, obsessive control freak. (laughing)

What is your typical day like? Are you having adventures every day? (laughing)

Not at all. There are certainly people whose entire lives are adventures, like people who live in the mountains and guide others on expeditions to pay for their lives, but I’ve always enjoyed two bits of life. I have my adventure life, when I’m away on expeditions, and then I have my normal life, which is pretty similar to a lot of people, really. I spend most of my day behind a computer, writing and making stuff, and then I try to squeeze in some exercise and sleep, just like normal people. I like having two different lives, though—I like sitting at my desk, writing a book, but I also like sitting atop a mountain and howling at the sunset.

What music are you listening to right now?

Most recently, I’ve been listening to The National and The Airborne Toxic Event. When I need to relax, I listen to Joni Mitchell, and I’m also a bit of a Bruce Springsteen addict: I’ll put “Thunder Road” on repeat and play it loudly when I’m trying to write. (laughing)

Any favorite movies or TV shows?

I hardly watch any TV, except sports. I love watching soccer and cricket. As for films, I tend to like quirky biographies. This year, I’ve watched three great films, one of which was Searching for Sugarman. Have you seen it?

Yes. It’s very good!

It’s amazing! The other two films I’ve really enjoyed this year are Jiro Dreams of Sushi and, most recently, Woody Allen: A Documentary. All of them are about creative people who are trying to do amazing stuff in their own worlds.

Do you have a favorite book?

I recently had to do a talk about my six favorite books, and I agonized over it. (laughing) My favorite travel book is As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee. My favorite fiction is either East of Eden by John Steinbeck, or Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls.

What is your favorite food?

One of the projects I started in order to teach myself to become better at filming and “traveling” without traveling is exploring an A to Z of foods in London. The goal is to eat at a restaurant from one country for each letter of the alphabet, all in London. For example, A for Afghani food, B for Bolivian, C for Cambodian, and so on. I’ve been working through the alphabet like that, and I’ve made it to the letter V. We make a short film for each one. My favorites so far have probably been Japanese, Cambodian, and Georgian food. US was very good, too!

You have all of that in London?

Yeah, except for O for Oman and Q for Qatar—I failed on finding food from those countries. I’m sure you could do this in New York City as well—it’s been a fantastic project. It’s been good for eating food I’ve never eaten before, and being in all the different restaurants is almost like being in another country. It has also taken me to parts of my own city that I didn’t really know before.

That’s a great idea!

You should try it.

Perhaps I will. Alright, I have one last question for you: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Adventures have had such a big impact on my life that I want to inspire other people to have them. When you do anything tough, it teaches you a lot about yourself. I’ve become more self-aware of the things I’m not very good at, but I’ve also gained self-confidence about things I am good at. Adventuring has made me more ambitious with my life and more compelled to try to fulfill my potential. It has driven me to make the most of all the opportunities I’ve had, and it has given me a lot more focus. More than anything, though, it’s just a lot of fun.

Adventures have also given me a great perspective on the world. I’ve seen many places, and what amazes me the most is the amount of random acts of kindness that happen, particularly if you’re alone or on a difficult trip. People have been so nice to me. When I was in the Middle East, people constantly stopped to offer me food and water. When I traveled through Siberia, people took me into their house because it was –40ºF; then, the next morning, they gave me a note and told me, “Our cousin lives in the next village. Give him this note and he will put you up for the night.” One time, I was cycling through Alaska and a lady pulled over on the side of the road to give me a whole pizza; she said, “I reckon our family can manage with one less.” These little acts of kindness happen all over—traveling and adventuring shows you that it’s a very good world out there.

“…what amazes me the most is the amount of random acts of kindness that happen, particularly if you’re alone or on a difficult trip…These little acts of kindness happen all over—traveling and adventuring shows you that it’s a very good world out there.”