- Interview by Tina Essmaker July 31, 2012

- Photo by Mr. Jakyl

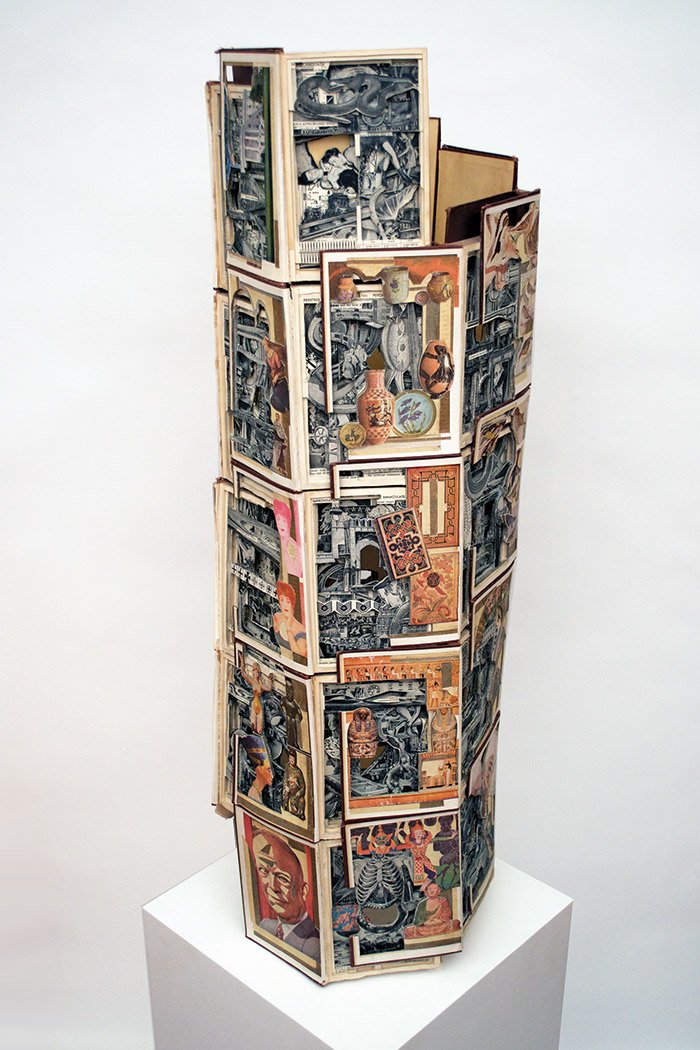

Brian Dettmer

- artist

Originally from Chicago and now living and working in Atlanta, Brian Dettmer is known for his detailed and innovative sculptures with books and other forms of antiquated media. His work has been exhibited internationally in galleries, museums, and art centers and has gained international acclaim through internet bloggers and traditional media. He has been featured in the New York Times, Wired, Esquire, and NPR, among others.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming an artist.

Basically, I’ve been an artist ever since I can remember. As far as being a professional artist, I finished school in 1997 and for almost ten years after that, I worked in sign shops and at The Field Museum of Natural History as a graphic shop supervisor. I always had a day job in graphics, signage, and communications, but then at night, I would work on my art and hardly get any sleep. Fortunately, for the past six years I’ve been able to focus full-time on my art.

Was it a slow transition into that?

To a degree it was. There was a number of years where I was working full-time during the day and then focusing on my artwork at night. I was in Chicago and had already had a couple solo shows in that area, so I was known regionally. In 2006, a gallery in Mexico City called Art & Idea picked up my work, took it to MACO, an International art fair in Mexico City, and did really well—they basically sold every piece they took. They told me they wanted to give me a solo show in New York because they were opening a gallery there. At the same time, my wife was offered a job down in Atlanta, which is why we moved to Atlanta. The timing was good because I had to quit my day job to move and the gallery in Mexico City had sold everything, so I had enough money to keep me going.

The gallery wanted to give me a solo show in six months and I had no work because they sold everything. Right when I moved to Atlanta, I was able to focus on creating work for that first solo show in New York. I knew it was make it or break it. After that show, I’d see what would happen and I’d know if I was going to have to go back and get a day job. Fortunately, that show went really well and then I was picked up by Toomey Tourell, a gallery in San Francisco, and offered a show there and then by MiTO Gallery in Barcelona and I haven’t had to seek any opportunities since then. I’ve been very fortunate to be able to focus on my work.

That’s awesome. It’s interesting to hear about all the work you put in prior to getting offered the show in New York.

Definitely. And I’m only 37 now, so this all happened when I was maybe 31, which is still very young for being a fine artist. Especially now when people are so impatient and want their career to take off right when they’re done with school. For me to have that happen, even in my 30s, is still pretty early. A lot of people struggle for dozens of years or just give up on their art; unfortunately that’s what happens to most people. I’ve always been stubborn and delusional enough to continue to make work no matter how people respond. (laughing)

Was creativity a part of your childhood?

Yeah. I’ve always been known as the artist or the kid who liked to draw and paint. For a short period of time, I thought I might want to be an architect or a chef, but I was always an artist. My parents thought I was talented and creative and they encouraged it, even if I was doing some strange things that they didn’t necessarily understand. Being creative was never something I intentionally sought out; it’s just the way I see things.

You said you were born in Chicago?

I was born just outside there, in Naperville. It was the fastest growing city in the country while I was there. As soon as I turned 18, I moved to Chicago to go to Columbia College.

Did you get a BFA?

I got a BFA from Columbia and every year after that, I kept thinking I should go back and get my MFA until I was at the point where I was working with a bunch of people with master’s degrees and they were all in debt. I realized it wasn’t necessarily something I needed.

It’s funny. If I could go back, maybe I would have gotten my master’s right after undergrad, but after being out for a number of years and having things continue to go well, it just didn’t make sense to go back. After a certain point, everybody looks at your work and not necessarily your education. Even though I went to college, I sort of consider what I do to be self-taught because I discovered working with books after school. No matter what kind of schooling you have, I think almost every artist is self-taught to a degree, if you’re doing something unique and original.

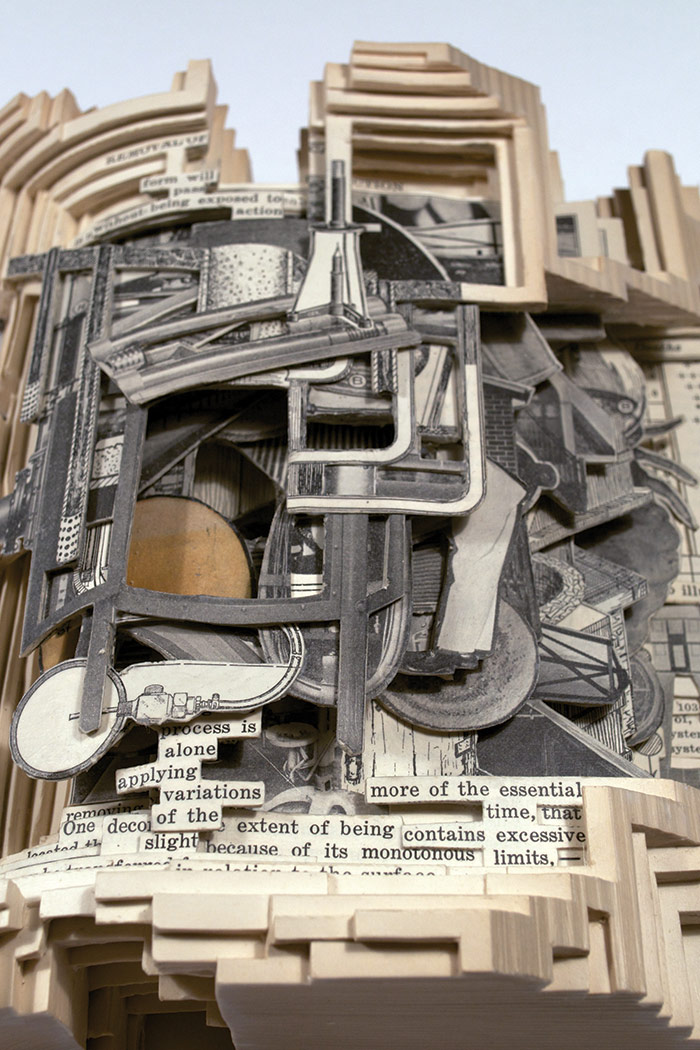

I watched a few of your videos about your process and how it evolved into what you’re doing with the books. What I found intriguing is that when you’re carving out the pages, you don’t know what’s on them because you seal up the books. Essentially, you’re discovering as you go.

Yeah, and that’s what keeps it exciting for me. It’s similar to reading because I have no idea what’s coming next or what will be on the next page. Once I set up the initial structure or form, I know what that is, but there’s such a high level of chance while I’m working. I never know how the finished piece will turn out.

Where do you get your books from?

All over the place. I have a favorite vintage bookstore here in Atlanta and they know me well and know what I do. On eBay, I’ll search for books on certain subjects, but half the time I’ll buy something and when I actually get it in my hands, it won’t necessarily work. The type of paper, the size of the book, the quality—all of that matters. I go to estate sales and I often have people contact me to ask to donate books to me. Right after the feature on CBS news, I had a big rush of people wanting to ship sets of encyclopedias to me.

“Even though I went to college, I…consider what I do to be self-taught because I discovered working with books after school. No matter what kind of schooling you have, I think almost every artist is self-taught to a degree…”

It’s fascinating to me how you’re taking physical, tangible objects with a lot of history and making something with them in a world that is becoming very much digitized.

My work is really a metaphor for that—for people to witness what’s happening digitally. We can’t find photo or text files from two to five years ago, but we’re never going to lose a note from our grandmother from 50 years ago. It might get lost, but it’s not going to suddenly disappear. Now that we have to get new devices every few years, it’s a constant updating just to maintain all these files and photos that we’re recording. And if we were ever to have an energy crisis, all of our personal and cultural records would go down with it. It’s really less stable than print. I think it can be debated that print is more environmentally friendly because you don’t have to have that constant energy of electricity pumping through in order to keep your records vital. You have it; it’s there and it’s done. And it’s tangible. I think that’s something we’re missing in digital media.

Was there an “aha” moment when you knew that art was what you wanted to do?

I think it was while I was in college. One of the reasons I went to Columbia College instead of the Art Institute—I was accepted into both—was that I thought I would concentrate on graphic design or animation because even though I was an artist, I knew I needed to have a job. About two years into school, I decided to focus on fine arts. I made up my mind that I would do whatever I had to do during the day to make a living, but the most important thing to me was to create my own work. I think it was really in my second year of college when I realized that no matter what happened, I would be creating my own work and that’s what I needed to focus on.

Even while I was working various jobs in design and signage, whenever I’d get promoted, I never wanted it to become a career. I always tried to resist taking over a new position because of that.

Did you or do you have a mentor? Who was it and how did they inspire you?

I did while I was in school. I’d say McArthur Binion was an influential teacher. There were others, not necessarily personal mentors, but people whose work I was familiar with—Buzz Spector, who is also from Chicago, and Melissa Jay Craig, who works with books. Seeing artists working with books in different ways allowed me to think, “This can be an art material.” They both do work completely different than what I do, but they opened my mind.

When was the first time you did a piece with a book? Was it intentional?

Right after college, most of my paintings at the time were done with text. I started ripping up books and applying them to the canvas and then ripping them off again. I liked the idea of the book actually being on the surface of the canvas. I felt guilty about ripping up books, but was also intrigued by the visual texture, content, and meaning that was already implicit in the material. I started looking at books themselves and sealing them up—this was around 2000—and digging holes into them and thinking about the dichotomy between physical labor and reading or learning things intellectually. Then I started finding and working with books that didn’t have a use or weren’t functional, like old construction catalogs or orphaned encyclopedias from thrift stores.

I had an “aha” moment around 2001. I was digging a hole into a book, not knowing what was going to happen, and I came across a landscape and started carving around it without thinking about it. A couple pages down, a figure emerged and I carved around that and just kept going. It was exciting for me because I had no idea what was coming next. I knew right away that it was like reading and that something important was happening, but I also didn’t want it to become gimmicky. I wanted the true nature of the book to come through without exploiting it.

Was there a point in your life when you decided you had to take a big risk to move forward?

The first risk would probably be when I decided to focus on fine art instead of design. The second risk might have been quitting my day job, but because we were moving and I had a show lined up, it didn’t seem like a big risk at the time. Now, when I’m doing something completely new, it can be a risk because I can spend months working on a piece and structurally, it might not work.

How long does it take to do a piece?

It depends. If it’s a single book, it can take two to five days. Larger pieces can take anywhere from two to five months. I’m in the studio at least 40 to 50 hours a week and usually more than that right before a show.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do and who has encouraged you the most along your creative path?

They are. My wife is very tolerant. I’ll tend to obsess over things if they’re not going well, if I have an idea that isn’t fully formed yet, or if I’m just struggling with a piece in the studio. Just like any job, you don’t want to smother your partner with your own professional problems, but she’s very supportive and insightful and has a good voice in the direction of my work. My friends are supportive as well, for the most part. It can be difficult when you reach a certain level of success and you have friends who are going down that same path and things aren’t happening at the same time. But between having a wife, a three year-old, a house, and a busy career, we have a handful of friends. Everyone is supportive of what I do and excited about whatever news I have or the next chapter of work I’m headed into.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I do. Most of my work isn’t really about myself. It’s more about the history of the book, the future of the book, and what’s happening now. It’s about media and technology and the way we record and perceive information and keep records. I do hope that my work is contributing to a larger discussion about information, technology, media, art, and communication rather than being personally about myself.

“I felt guilty about ripping up books, but was also intrigued by the visual texture, content, and meaning that was already implicit in the material.”

Are you satisfied creatively?

Yeah, for the most part I am. I always have to be in the studio. If something isn’t going well, I might not be satisfied creatively at that moment, but then I’ll hit a point where I do know how to resolve it. It can be difficult and because of the time my work takes, it can wear on me and become hard to focus mentally and physically. But yeah, I am thankful to be able to explore any ideas I do have and in that way, I am satisfied creatively.

Do you have any hopes or plans about what you’d like to be doing in 5 to 10 years?

I try not to plan too far ahead. Right now I’m lucky to be in a few museum shows and I have another show that I’m working on that will be opening in Atlanta this summer at The Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia and will then be traveling to a number of museums, art centers, and libraries around the country. My goal is to focus on more museum shows and to be included in more important collections around the world so that that history is saved. Also, I’d like to be able to continue to explore my own ideas without feeling pigeon-holed or rushed.

Any different avenues that you plan to explore?

This year I’ve expanded on my shift into other materials. I’m working on a large print that’s going to be a three color screen-print. I looked up the word “chaos” in the thesaurus; it had six synonyms, which I also looked up; out of those synonyms, there were 49 more words and it kept growing into this radial chart tracking the conceptual path from the meaning of one word to the next. Of course, it gets to an obsessive degree. It’s about the book, but it’s not of the book. I’ve been experimenting more with prints and I’m working on a series of photographs as well. I’m continuing to focus on the book as a subject, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be the material in all of my work.

If you could give a piece of advice to a young artist starting out, what would you say?

Keep doing what you’re doing and try to expand it at your own pace. Don’t feel forced to go in any single direction until you’ve experimented with all outlets.

The two things I always tell young students when I talk to them is that it’s very important to learn to photograph your own artwork really well and know how to talk or write about your artwork really well. Especially now that a lot of your initial exposure could be online, it’s important to have really good images and be able to communicate about what you’re doing.

How does living in Atlanta impact your creativity? There seems to be a lot going on there these days.

There is and it’s kind of exciting. I’m from Chicago and Chicago is constantly comparing itself to New York, so there’s this weird, little brother mentality to the city. It’s ridiculous comparing yourself to New York. Maybe LA can do that, but as far as the art scene in Chicago goes, it’s frustrating to even try to compare the two.

I moved from Chicago to Atlanta and this is a very inexpensive place to live, it has a great airport, and there aren’t too many distractions. For me, it’s a great place to focus on my work. I travel enough that I get a well-rounded cultural experience. Because I can travel or get online, I stay connected to what’s going on in other cities. Here, I’m able to focus on what I’m doing and work at my own pace.

There’s definitely a lot going on here and it’s a pretty young city in the fact that a lot of people who live here aren’t even from the South. Unfortunately it’s also a transient city too. A lot of people move here for jobs and then they’re off to the next city. The local art scene is pretty healthy, but again, you can’t compare it to NY, LA, or London. However, I’m fortunate to be able to live anywhere and do my work.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

It’s important to a degree. I work with the Saltworks Gallery here and there are some great artists who they show. I’m able to have conversations with the other artists as well as the gallery staff, but I’ve never been the hang out at the coffeehouse type of artist. Even when I was in school, some of the students would hang out, have conversations, and work in the studios. I would go home, focus on my work, bring it back a week later, and the teacher would say, “Whoa, where did this come from?” I enjoy that solitude while I’m working. It’s important to stay connected, but if you get too involved with that, it’s going to be difficult to have your own unique vision or resolve your own ideas yourself. It’s a trade-off having the solitude and space and quietness, but not having the type of community I would have in someplace like New York.

What does a typical day look like for you?

For the most part, I get up around 7:30am, take my daughter to daycare, and since I have no commute, I end up right back at home. (laughing) I’m in the studio from 8:30–9am until 5pm and focus on my work at least eight hours a day. I have an assistant who comes in two to three days a week. I’ll pick up my daughter, eat dinner with the family, my daughter will go to sleep around 8–9pm, and sometimes I’ll get back into the studio for a few hours again in the evening. Or sometimes I’ll wake up at 5am and get a few hours in the studio before anything happens. That’s a typical day.

Any current albums on repeat?

I’ve been listening to a lot of podcasts recently. It depends on what type of work I’m doing and how much attention or focus my work takes. I’ll listen to music, NPR, podcasts, or audiobooks. I never listen to music with lyrics while I’m working—it’s mostly instrumental, electronic music like Mogwai or music I can zone out to that will help with my flow. I’ve also been listening to Clint Mansell, who does all the scoring for Darren Aronofsky’s films.

Any favorite movies or TV shows?

I got into The Walking Dead, partly because it was set in Atlanta and anything post-apocalyptic is interesting to me. I’m a big Werner Herzog fan. His most recent one, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, was fascinating.

Favorite book?

I keep talking about this book called The Shallows by Nicholas Carr. It’s about the influence of the internet on the way we think and what might be happening with books in the sense that we’ve trained ourselves to focus on the long duration that a novel or book requires and now we’re sort of going back to this intuitive, hunter-gatherer mode when we’re collecting information online.

I do listen to a lot more books than I actually read because I have a lot more listening time. I’ve recently listened to all of the Oliver Sacks books. I also just listened to Imagine: How Creativity Works by Jonah Lehrer. And all the Michael Pollen books about food fascinate me.

Speaking of food, do you have a favorite?

All types of food, but I really like slow-cooking ribs over charcoal and any type of Mexican food.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I’d like to be remembered for doing something completely new at a pivotal moment when it’s important for us to reflect on what’s happening with books—much like when printing and photography became commonplace and everyone thought painting was going to die because it wasn’t necessary anymore. But that’s when painting became most creative and that’s when modern art emerged, because painting no longer had the obligation to be the primary source of image-making or communication. I think that’s what is really happening with books right now. There are newer technologies that can take that responsibility and people think that books might die, but in a way, it frees the form of the book up to become something completely different, whether it’s through literature or through the way I’m handling it as sculpture. I hope that I’m remembered as one of the primary artists to explore the medium and break open new possibilities.

“I’d like to be remembered for doing something completely new at a pivotal moment when it’s important for us to reflect on what’s happening with books…”