- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker July 2, 2013

- Photo by Andrew Elliott

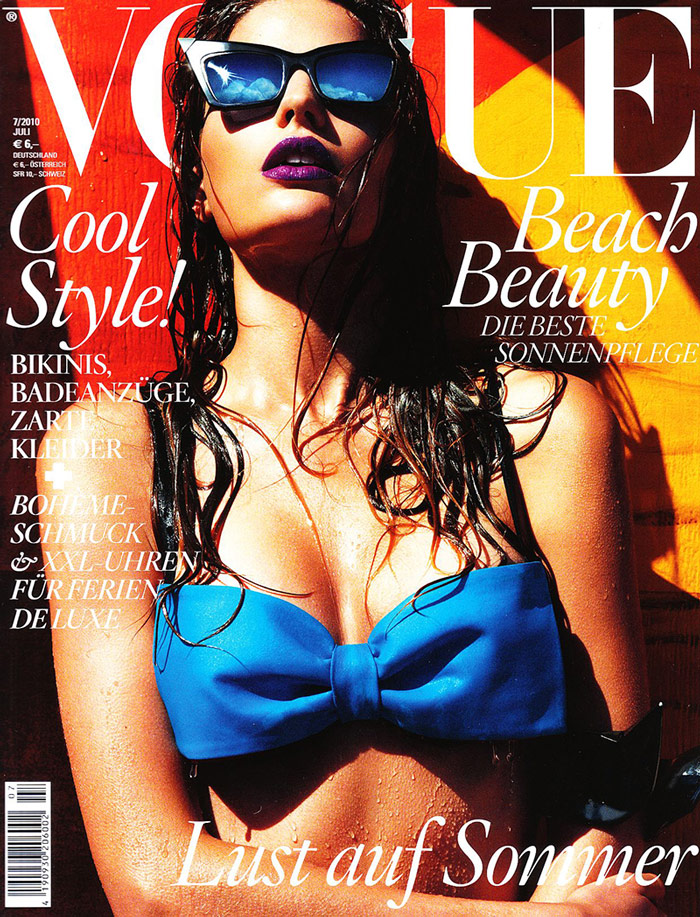

Cameron Russell

- artist

- entrepreneur

- model

- publisher

For the last decade, Cameron Russell has worked as a model for clients like Prada, Calvin Klein, Vogue, and Elle. She uses her unique background to bring alternative content and culture to the mainstream. She studied at Columbia University, where she wrote her thesis on grassroots public art and political power. She is a founder of Space-Made, which seeks to empower grassroots creators to speak and work as experts and problem-solvers.

Interview

For our readers who don’t know, what are you working on right now?

My day job is modeling—that’s what I get paid for—and my part-time, night owl job is starting up this art lab. We’re trying to figure out how to ignite networks of power—that sounds very convoluted and lofty (laughing)—through building participatory art via media platforms.

Are you referring to The Big Bad Lab?

Yes.

Is it a startup?

Sure. We operate like a consultancy and have a couple clients, but there were no startup costs other than our time.

Awesome. So, what was your path to doing what you’re doing now?

I feel like I might be repeating myself from my TED Talk, but everyone asks me how I became a model. Technically, I was scouted on the street in New York. But since that says so little, I think the real answer is that I won a genetic lottery and inherited a legacy. I say I won a genetic lottery because we have this idea from watching America’s Next Top Model that anyone can model if they try hard enough, but it’s something you either have or don’t have, genetically speaking. For example, I weigh 115 pounds and my grandma weighs the same; having that body type is genetic and out of my control. When I say legacy, what I’m getting at is that most models are white and there is a very Western idea of what beauty is.

I started doing what I’m doing now because I’ve always been obsessed with politics. Actually, I wanted to be president for a really long time. When I’d tell people, they’d ask, “President of what?” The United States, of course. (laughing) Once I grew older, I became disillusioned, which I think might be the experience of many people in our generation because we grew up with such partisan, moneyed politics. I remember sitting in a political science class my freshman year of college and the teacher asked what our first political memory was. Nearly everyone said the Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky scandal. That is a stupid political climate to come of age in. I hope we don’t forget the 60s and 70s when a lot of people were organizing and achieving things that were exciting.

I love grassroots politics. Because I’ve worked in fashion for a long time and am aware of how powerful culture and advertising are, I’m really interested in figuring out how to use culture, art, and media to facilitate people’s efforts to participate. How do we make people creators of content that is impactful?

There are a lot of story-based examples of what I mean. A good one is that, if you study American political science, the people who are the least likely to vote and organize are Black and Latino men. Yet the fastest visual change of a city ever was 1970s New York and it was carried out by 8–16 year old Black and Latino boys. That’s an occasion where, for them, the tools to make change were accessible and there was an opportunity for anyone to succeed. Early on, it wasn’t so much as much about visual art; it was about putting your tag wherever you could. Anyone could become a king—they just had to be dedicated. I think those two elements—accessibility and ability to succeed—made the movement explode. I’m trying to apply that lesson to other things. For our generation, I think campaign finance and climate change are absolutely the two biggest issues we’re facing that will not likely be solved by government or big business; we have to figure out another way.

“…everyone asks me how I became a model. Technically, I was scouted on the street in New York…I think the real answer is that I won a genetic lottery and inherited a legacy.”

You were scouted as a model when you were young and have been doing that ever since. What was your educational path?

I went to Columbia to study political science and economics.

How long ago did you start The Big Bad Lab?

Some friends and I started it last summer. It was casual. We threw an art hack day focused on campaign finance reform. We all had other jobs, so it took some time to talk through possible projects to work on. A month or two ago, I got serious about a few projects: Interrupt Mag, an Android app that I’m not going to talk about, but it’s really exciting—like everyone in New York says—and a couple other small art projects.

Your TED Talk changed things for you. Do you want to talk about that?

Sure. I think the talk I gave really gets at what we’re thinking about at the Lab, which is that if you use culture and art, you can talk about complicated political things. I talked about race, privilege, and access to media, which are things that most people don’t want to listen to, but that talk went viral because I’m a model who was talking about modeling and fashion and things that everyone can have an opinion on. I was recently talking with an organizer for the Queens Museum of Art and asked about the difference between a community organizer and an arts organizer, which is what he does. He said that when you’re talking about what color a public space should be or what cultural event should happen there, everyone has an opinion. When you’re talking about an issue that’s labeled political, people often feel like they cannot give input because they think they’re not well educated on the issue, or their opinion or vote hasn’t mattered in the past and they’re disenchanted with “politics.”

I suppose I could say I’ve experienced a similar thing. When I introduce myself as a model, almost anyone will talk to me, whether it’s a 13-year-old girl or a senator. If I introduce myself as a political science major from Columbia or say I’m working on a thesis about political power, fewer people are interested or engaged. Culture can be used as a way into important conversations and that is why it was exciting to hear people’s responses to the TED Talk. I was on CNN with Soledad O’Brien, talking to a Tea Party senator about whether he was elected because he is a white man or because of skill. That’s a discussion we don’t have very often, despite the fact that only 17% of Congress is women and a small percentage is nonwhite. Obviously, something is going on.

The other thing that came out of my TED Talk was Interrupt. We decided to start that through The Big Bad Lab after tons of press came to me asking about the talk. I wanted to have a public conversation about access to media, but when the only person talking about the issues is the person who has full access to media, it doesn’t make any sense. We needed to involve other people in the conversation.

Did you start by asking for submissions to Interrupt?

It started with an open call. I was getting a ton of press and decided to try to redirect people’s attention. We got several hundred submissions. Then we started doing specific asks and got even more submissions. That’s how it started.

One of the questions we like to ask is about how creativity was a part of your childhood. In general, what kinds of things did you imagine or enjoy doing when you were younger?

My mom did not really believe in toys, so I was definitely creative [laughs]. We had a dress-up box, which was full of weird things my mom found at the thrift store. We also had a home video camera, so there are a lot of videos of us dressed in bizarre clothing. We also had a lot of boxes that my dad stole from FedEx, which we used to build life-sized forts.

Where did you grow up?

In Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“…becoming a model was very counter-culture for my background, which is hyper-liberal, academic, and feminist. Some people were definitely horrified…but it was a blessing and allowed me to pay for college and have the freedom to work on projects of my choosing…”

You mentioned wanting to be president when you were young. Tell us about that.

I was obsessed with being president from ages 4 to 20. In high school, I went to the Naval Academy Summer Seminar because I thought I might go to Annapolis—it seemed really important for someone who wanted to be president to serve.

(all laughing)

Tina: You were serious!

Yeah, I was. I also worked on John Kerry’s campaign when he ran for president. When I was much younger, I worked on Jarrett Barrios’ state senate campaign. I did a lot of political things as a kid.

Did you have an “aha” moment when you knew what you wanted to focus on?

I’m not someone who ever walked around New York thinking about graffiti, but then I read a book by Jack Stewart called Graffiti Kings. Jack Stewart became provost at Rhode Island School of Design in the 80s, but before he could be provost, he had to write a thesis to earn a PhD. During the 1970s, he had spent weekends interviewing kids who were graffiti artists. He followed the development of graffiti and figures like Tracy 168. It’s not a political book, but it struck me as political and the subjects seemed like political actors. As an undergrad student, I started to interview various graffiti artists and street artists. I was talking to BG183, who is part of Tats Cru in the Bronx, and when I asked him about his motivation for writing, he said, “I wanted to be like the mayor. I wanted my name everywhere.” It was perfect. It’s a different structure, but it still is about power.

Did you have a moment when you shifted from wanting to be president by going through the proper channels to deciding to lead more of a grassroots effort?

Hmm. I guess that it might have been when I was watching the Bush Presidency as a kid, seeing the insane televised Shock and Awe. I knew that wasn’t the kind of president I would want to be. Then I saw Obama carry on the legacy of bad foreign policy—I’m boring you guys to death! There’s this essay called “Oligarchy in America” by Winters and Page, which is all about campaign finance. After reading that, I really started paying attention to the issue and it’s devastating. Then there’s the slow to nonexistent response to climate change—I could keep going. I even felt like a lot of my advisors from when I was young have also become disillusioned about what electoral politics in the United States can bear.

Another part of it is being totally lucky in ways that are hard to sometimes even notice. If you’re a model, it’s very blunt how lucky you are. I went from making $5 an hour at an after-school job to making an insane amount of money—more than what my parents ever made—and I was only 16. It was complete luck and there was no barrier to entry—I didn’t have to take a test and there were no skills required. That made it so apparent how luck factors into all these other things. It made me less interested in electoral politics because I don’t think they’re representative.

Tina: What you’re doing is much more democratic because you’re going straight to the people and, in the case of Interrupt, you’re trying to help remove the barriers so people can be heard.

We love to imagine that the Internet is really democratic, but it’s not. Last year on YouTube, the top ten most watched videos ever were created by professionals. To maintain whatever semblance of democracy of content, we need to introduce high-production content creators to everyday users. Yesterday we got a beautiful submission for Interrupt that was totally out of left field. It was about Sailor Moon; we started reading it and it turned out to be a really moving story about a young girl who grew up in New York with divorced parents. Because we have illustrators in our network, we can make that content come to life and become competitive in our media-saturated environment.

Eventually, when and if we have ad revenue from Interrupt, we want to pay our contributors because participatory media outlets, like the Huffington Post, usually don’t pay contributors. That’s insane. We want to have trust with a network of collaborators who we can pay for their contributions. That’s the long-term goal.

Ryan: We’d love to be able to do stuff like that down the road, too. It frustrated me to learn that even a lot of these cool, indie magazines don’t pay their contributors for content—and the content is super high-quality.

Ugh. How do we change that?

Ryan: It’s that whole thing where people do it because it’s cool and gives you exposure. There’s a certain truth to that, but I also think that people take advantage sometimes.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Well, I love my mom—hi, mom! When I was a kid and obsessed with becoming a politician, I thought Benazir Bhutto, who I saw speak in Cambridge, and Angela Davis were awesome. Even though Margaret Thatcher did a ton of bad things, someone gave me a children’s book about her when I was seven or eight and I thought she was cool, until I realized she was a maniac. Also when I was eight, a mentor of mine who worked for the Clintons introduced me to Bill Clinton. In college, I became obsessed with fiction writers, like J.M. Coetzee. I also have to mention Tibor Kalman; I admire Colors and everything he did.

You’re early in your path, but have you taken any big risks so far?

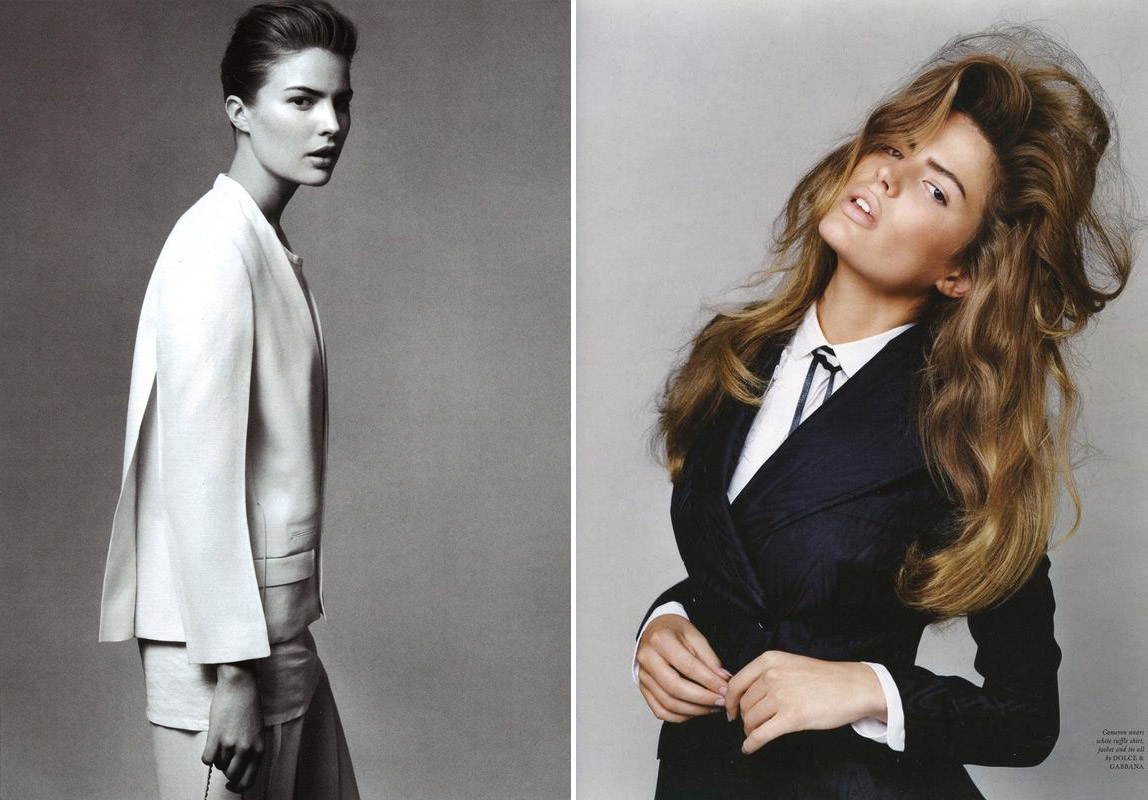

I don’t know if it was a risk, but becoming a model was very counter-culture for my background, which is hyper-liberal, academic, and feminist. Some people were definitely horrified that I would become a model, but it was a blessing and allowed me to pay for college and have the freedom to work on projects of my choosing on the side.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Most of them think it’s hilarious that I’m a model. I joke with my law school friends when we go out by telling them, “I’ll get the tab now, but when my résumé reads ‘underwear model, twenty years,’ you’ll get the tab.” (all laughing) And my family is supportive; they’re awesome.

The answer to this seems evident, but do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I do, but I don’t know how yet. I’ve been trying to figure that out. I’ve been thinking about climate change a lot recently. We’ve passed 400 parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere and are on a doomsday path. By 2060, we’re going to see a 7° temperature change, which we haven’t seen since the Ice Age. I’ve been asking myself how we can talk about that and frame it differently so that it’s not just an intellectual liberal argument. I leave my house and turn my lights off or go to the supermarket and bring a bag with me, but what does that do? We should think about having a higher purpose. I think the challenge for my generation is that we don’t know what we can do. I’ve been trying to figure it out, much like everyone else.

“We should think about having a higher purpose…the challenge for my generation is that we don’t know what we can do. I’ve been trying to figure it out, much like everyone else.”

Are you satisfied creatively?

Well, the thing with being a model, which I touch on in my TED Talk, is that it’s never your vision. You’re always someone else’s vision. You’re playing the character that the stylist, makeup artist, photographer, client, and art director have developed; no one asks me what I want. But because I’m a model, I have the luxury of having this other job where I can experiment and do all the crazy things I want to do.

Traditionally, modeling careers don’t last forever. Are the things you’re setting up now the things you hope to focus on next?

Yeah, I kept thinking my career would be really short, but I’ve now been modeling for 10 years. (laughing) I keep getting asked to do jobs, so I keep saying yes. I don’t know when it will end. I am doing lots of things on the side, and if I’m working on something that’s more important than a job, I’ll say no that day. Modeling is easy to trade off because there’s no long-term commitment, which allows me to re-evaluate on a job-by-job basis.

If you could give a piece of advice to a young person starting out, what would you say?

Hmm, I don’t know. My own personal goal is to try to take things as far as they can go. I am fairly self-motivated. That probably comes from the thousands of papers I had to write on red-eye flights when I was still in high school and college. But I also understand having to do things for money. I guess my advice would be, if you have the luxury of a creative exploit and you’re not doing it for money, then don’t half-ass it!

How does where you live impact your creativity?

Oh, god! I’ve lived here for too long.

How long?

I was going back and forth when I was in high school, so it’s been about 10 years including that time.

New York is actually fantastic creatively because there are a lot of people who are really creative and hard-working. Many people have a full-time job plus a side job. And yes, they will agree to do a crazy creative project with you because that’s what they’re here for. Everyone is creating and there is a lot of support for that here. Also, because it’s so big, I think there are a lot of ideas that get mixed together. You can explore how people are combining youth work and art or Occupy and art or tech and art. There are some interesting collaborations happening.

Tina: You mentioned street art earlier. I saw the website you made for your senior thesis on street art. Are you still doing anything with that project?

I was going to publish it as a zine, but I got so excited that I decided to make it into a book. Now it’s just a sad half-book sitting on my desktop. I am talking to a publisher about it, but it’s one of my too many side projects.

I interviewed 60 public/street/graffiti artists about their work and put it in the context of political power. I didn’t ask political questions; I asked questions that I understood to have political implications, like, “Did doing this project increase your network of people?” I asked about things that contribute to the development of a political actor, but not in a formal language.

Tina: How did you reach out to the people you interviewed?

I did harass a couple people on the street—one asked me if I was a cop (laughing)—and I reached out to others by email. It was easy, though, because once I talked to a couple of people—as I’m sure you know—then they introduced me to more people. In New York, the grassroots public art scene is very open like that. I also went to Detroit, which has a huge, burgeoning grassroots public art scene. I was there for one day and interviewed six of the best people in the whole thesis.

Tina: That’s amazing! I went to college at Wayne State University in Detroit. They’re well-known for their social work program, which is what I studied.

Detroit is so awesome. Have you seen the TAP Gallery?

Tina: No.

Some teenagers and gangs were tagging garages in alleys in a neighborhood. A guy named Erik Howard organized and taught the kids how to do really amazing graffiti art. Together, they created big pieces on the garages, which are no longer getting tagged.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

I don’t know if I would consider my friends “creatives” or not. I think there’s some confusion, especially in New York, about how we define creativity. Often it has to do with privilege—someone is only an artist or creative if they’ve been in a gallery or if they’ve gone to school for it. I work with lots of people who might not put that on their résumé, but are still creative.

Tina: What about your cofounders at The Big Bad Lab?

I started the project with some girlfriends. One is a lawyer; one is a writer; another is an artist; and one is a journalist. I think that half of creativity is structure and hard work and the other half is the crazy part where you’re up late at night, thinking and working. There is something to be said for having people who are logical, rational, and responding to things in the real world when you’re having a creative discussion, because they make your ideas stronger and better.

As far as personality, I’m not a loner. I definitely need other people around me. My apartment, which is a studio, always has at least four people in it—it’s a disaster. (laughing)

What does a typical day look like for you?

When I’m shooting, there’s usually an 8 or 9am call time, unless we’re on location—then it’s evil, like 5am. I sit in hair and makeup for a long time, sometimes up to three or four hours—other times it’s 15 minutes! I shoot until 5pm or, if it’s an editorial shoot, I stay really late.

In the office, we’ve been doing a lot of things. Most of it is about community building at the moment. We’re meeting lots of different types of people and also doing stuff offline, like public art and workshops. We did a workshop with a Bronx-based youth program, WOMEN, and an organization called FORCE, which is working to end rape culture; we also did an Art Hack day at Harvard in Cambridge. We have an upcoming Art Lab in the Lower East Side from July 24-28, 2013, which I’m really excited for. We’re also printing a limited edition of a mock tabloid for Interrupt, which will be available soon. As a group, The Big Bad Lab works out of a space in DUMBO—it’s a funny old converted nunnery next to a chapel.

What are you listening to right now?

The LBJ audiobooks, The Passage of Power (The Years of Lyndon Johnson), are really good. The album I’ve been listening to recently is Meshell Ndegeocello’s newest one, which is beautiful.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

Scandal and that one on Netflix—House of Cards. I watched all of that over a long weekend Upstate. When is the next season out?

We don’t know.

I was watching Game of Thrones, but this season has been disappointing. I’m over it now. Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, which just came out on IFC, is awesome.

Your favorite books? We’ll let you name a few.

(laughing) Okay. I just read a fantastic book called Confront and Conceal about the Obama administration and foreign policy. I already said it, but Graffiti Kings is fantastic. The Miner’s Canary by Lani Guinier and Gerald Torres is one of the best American political books ever. I just finished a fiction book called Black Mamba Boy by Nadifa Mohamed and it was pretty good, too.

Your favorite food?

Mango with sticky rice, which I go to Sripraphai in Woodside, Queens, to get. I also like any kind of dessert or candy.

Tina: I’m a big fan of dessert, too!

You talked earlier about the legacy you inherited, but what kind of legacy do you want to leave?

I hope that our generation doesn’t destroy the world. Personally, I don’t know. I guess the conflict is that, even though the world doesn’t need anymore kids, I would like to have children who I have a really good relationship with and who I’m proud of—maybe I’ll adopt. Career-wise, I would like to figure out how to impact our political model to improve democracy.

Tina: That’s a big task. Good thing you’re starting early.