- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker January 9, 2013

- Photo by Chris Glass

Chris & Cameron

- designer

- entrepreneur

- developer

Chris Shiflett and Cameron Koczon are two of the partners at Fictive Kin, where they do good work with good people to create fine products. They’re also the organizers of Brooklyn Beta, a small, friendly web conference aimed at the “work hard and be nice to people” crowd.

Interview

Note: We met up with these fine fellas for a night of food, drinks, and conversation in our East Village neighborhood. The evening started off at Momofuku Noodle Bar for some delicious grub and continued with drinks at Cooper’s, where Chris discovered one of his favorite beers—Cuvée des Jacobins Rouge—was on tap. Of course, there was also plenty of whiskey drinkin’. Cheers!

A lot of our readers might know you from Brooklyn Beta, but you each have regular, full-time jobs, too. For our readers who don’t know, would you tell us what you do?

Cameron: I’m going to let Chris go first, because I talk too much. (laughing adorably)

Chris: We work together at a company called Fictive Kin, where we’re two of the thirteen partners. We have a really great team working with us there, all of whom are friends. We build web apps, but more than that, we’re building a lifestyle—what we want to do for the rest of our lives. That’s the focus.

I think we have a desire to create things we really love, that we can throw our hearts into and be proud of, and that other people love as well. We hope that what we make is meaningful, but in the same way that we don’t try to make Brooklyn Beta too preachy, we also don’t want to hold ourselves to an impossible standard. We want everything we make to have a purpose, but not everything has to save the world.

Tina to Chris: What is your role within Fictive Kin?

Chris: In some ways, we’re still figuring that out. I’m a developer by trade and am pretty good at various things like product design, security, writing, and management. My role over the years has adapted to meet the needs of my colleagues and I hope to continue that tradition. At Analog, my role was similar to Cameron’s and things have been a whirlwind ever since we decided to work together.

After Analog and Fictive Kin joined forces, I spent a lot of my time working on the new Brooklyn Beta site and getting Summer Camp started—writing copy, reaching out to potential advisors, reviewing applicants, and stuff like that. Of course, there was also a conference to organize and Summer Camp teams to mentor. Now that most of that is out of the way, I can focus on Fictive Kin stuff.

Tina to Cameron: And what do you do?

Cameron: It’s a mix of super fun things and super tedious things. Also, I’m saying the word “super” a lot. The fun bits are usually product or company culture centric, like choosing upcoming projects, working on product roadmaps, and planning our quarterly retreats.

On the tedious side of things, because we don’t have a big company, Tyler and I have to take on all of the admin responsibilities—he usually takes care of legal stuff and I do the accounting and other assorted gubbins.

You two are good friends and you’re in business together. The obvious question is how did you meet?

Chris: We met at Studiomates, so we have Tina to thank for that. I think we both ended up there for similar reasons. We sensed that design was going to play an integral role in the next iteration of the web and we wanted to surround ourselves with that and be part of it. It turned out to be a really good decision.

Cameron: Yep. Plus one. Design is why I moved to New York City. I ended up at Studiomates by random luck. I was reading Tina’s blog and saw a post for an opening in her space, which wasn’t even called Studiomates at the time. I was living in San Francisco, but like a champion, Tina rented me a desk without even meeting me. When I got there, it was me, Tina, a print designer, and an interior designer. Not a lot of Internet people.

Then, in August, I went out of town for a few weeks, and when I came back, Chris was there along with Chesley Andrews and I think Jessica Hische, too. Some personalities just click, and ours did—Chris and I became fast friends. We used to go to this place in Park Slope called Bierkraft every Tuesday night because they had a free beer tasting—they probably still do. We could meet a brewer, try a bunch of delicious beers, and then, because we had a bit more money than we do now and we were just realizing how much we had in common, we’d raid their beer fridges and tack on another few hours.

It was fun. I probably gained like ten pounds becoming friends with this guy. We later graduated to beer, pizza, and cowboy movies at my place because—

Chris: Because I needed a remedial studies course for cowboy movies. I hadn’t seen any of Cameron’s favorite cowboy movies.

Cameron: He had seen zero of the top seven.

Also, it doesn’t take a long time being around someone to figure out if they’re going to be a good compadre. There are little things that happen, like this story—Chris, do you want to tell this one? You tell it really well.

Chris: The Superfine one?

Cameron: Yeah.

Chris: Okay. I didn’t know Tina—or Cameron—very well when I first joined the studio. Now that I do, I know that Tina organizes lunches with interesting people all the time and it’s awesome. During my first lunch of that sort, I thought that the people we were eating with were her good friends and that I should be on my best behavior. I was sitting across from a developer who was trying to sound impressive, but he had absolutely no idea what he was talking about—a pretty rough combination. He probably didn’t realize I was also a developer. Under normal circumstances, I might have eventually said something, but this time, I didn’t. Instead, I played dumb and nodded along. I started to feel isolated and trapped and even wondered if joining the studio was a good decision.

Then, this guy made a weird comment about Apple outsourcing all of their design. Cameron’s good friend Tyler—who now works with us—was working at Apple at the time and managed their iPod line, so Cameron knew that statement was absolutely not true. Cameron spoke up, corrected the guy, and kinda put him in his place. He was polite about it, but I think this guy realized he was in over his head because he was pretty quiet after that. It wasn’t a big deal, but it was one of those early indicators that Cameron and I were gonna be good friends.

Cameron: I don’t think I was as polite as he says.

You guys met at Studiomates, but what were your paths prior to that?

Chris: I was a partner and CTO at a pretty big consulting company. At one point, we had almost a hundred employees split across two companies, with all the advantages and disadvantages that go along with that. My partner there was a super badass who was fun to work with, but over time, it started to become clear that our visions of where the company should go were different.

Cameron: That’s the G-rated version.

Chris: It’s also true. It’s awkward to be that far along in a partnership with someone and then realize that you have pretty divergent ideas about where things should go from there.

I was burned out and needed to regroup and figure out what I wanted to do. I was also out of the game because I had spent three or four years doing business stuff and managing people. I had great soft skills, but had done very little hands-on work. I had lost my hard skills and wasn’t making things or doing work that felt meaningful.

I became part of Studiomates before I really knew what was next. Then I met Cameron and thought he had his shit together; he thought I had my shit together; neither of us did. I guess it was a pretty good time to get to know each other.

Cameron: Going way back, I went to college and then got my MBA. After that, I co-founded a mechanical design consultancy called Pocobor—which is Robocop spelled backwards—with some good friends. We started in the garage of the house we were living in, doing a mix of client work and our own experiments. While working at Pocobor—and even a bit before—I started getting into design and front-end development. Ultimately, I fell more in love with the web and moved to LA to work at a startup. I was there for about a year, then left, and the investors bought back my equity, which I used to start Fictive Kin. That’s the very abridged version.

“…I met Cameron and thought he had his shit together; he thought I had my shit together; neither of us did. I guess it was a pretty good time to get to know each other.” / Chris

Was there an “aha” moment when you decided to join forces?

Cameron: I’m not sure if it was as much of an “aha” moment as it was an “oh shit” moment. It was probably around week ten or eleven of going to Bierkraft that we started talking regularly about the inevitability of us partnering up. Our teams were mirror images of each other. We were all friends. We hung out together online. We hired some of the same people. The line was already blurred as to where Analog started and Fictive Kin began.

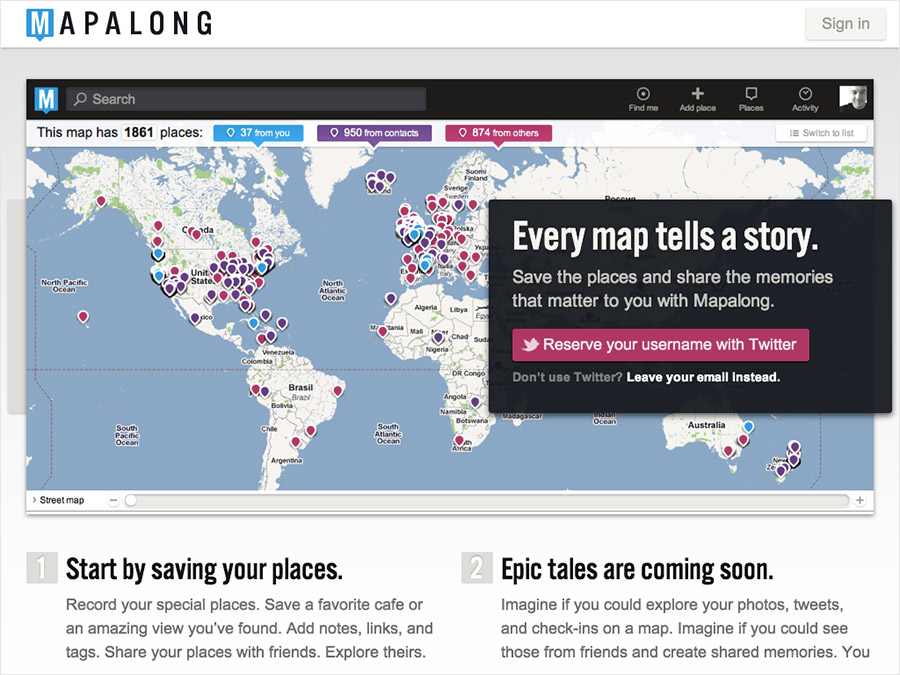

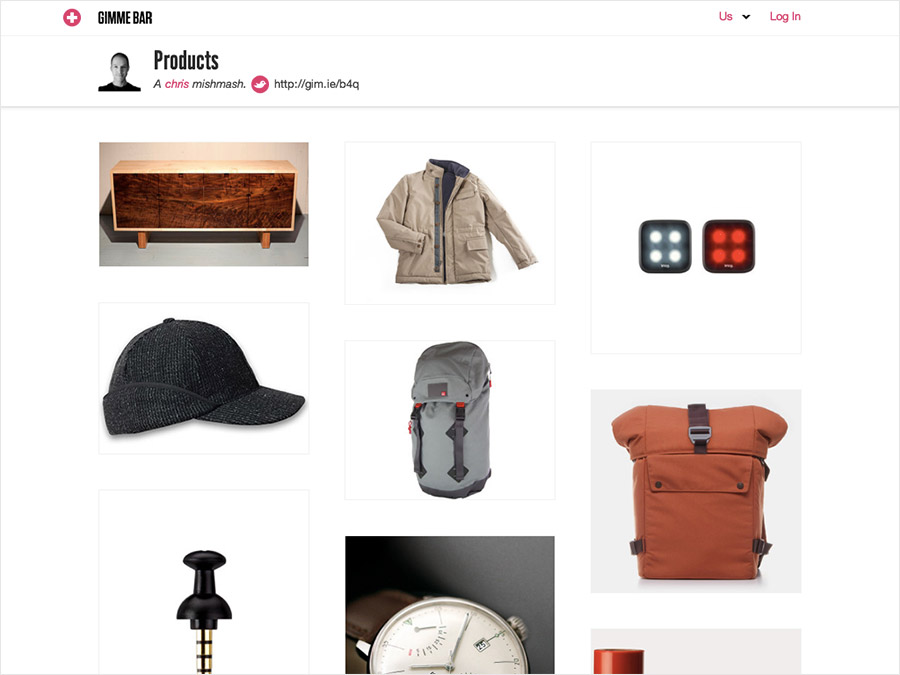

We had envisioned this post-success combination that we called Anakin, because it sounded better than Fictive Log—but we own fictivelog.com and not anakin.com. Gimme Bar would be a hit. Mapalong would be a hit. Then, with money concerns behind us, we would team up and build great shit together.

It didn’t really play out that way. Neither of our products were huge hits for reasons that we think we understand and plan to fix—fear not, Gimme Bar and Mapalong fans—but ultimately, the timeline got moved up quite a bit. It was more like a huddle together for survival than anything else. So far, so good.

Many of our readers know you from Brooklyn Beta. You two are the instigators behind that. How did it start?

Cameron: I always tell the story, but I don’t know if it’s the real one.

Chris: I think it’s multi-faceted. I wanted to do a conference with Analog and had even tested the waters by getting a group of designers and developers together at Beer Table to hang out, eat dinner, and drink beer. It wasn’t super ambitious, but it was cool to get people together and see worlds collide. This was almost exactly one year before the first Brooklyn Beta.

A few months after that, at Studiomates, Cameron and I talked about doing a full-fledged conference together. We got the discussion going and then Cameron and I went to the Future of Web Design. The entire thing was underground, which was depressing and uninspiring. The speakers were pretty good, but there were no breaks between the talks, and we sat in super long rows of people, so we felt trapped and just wanted to get out of there.

Cameron: We decided to skip out on the last few talks and went across the way to have drinks at this bar Chris knew about. They served great beer—including Celebrator—which was one of the beers Chris got me started on. We depleted their entire supply over the next few hours.

Chris: That experience cemented our idea of doing Brooklyn Beta. We started planning and because Sean had organized a few conferences already, he gave us some advice and even put together a budget for us.

Cameron: Everybody said, “Doing a conference is way harder than it seems,” and I didn’t think it would be—but it definitely is. Even our first conference with barely more than a hundred people, one day, and six speakers was a surprising amount of work.

Also, when it comes to conferences, it’s much more real-time than you’d expect. It’s not like a blog post where you get it just right and then share it. You watch it unfold at the same time as everyone else. Speakers cancel—one year I had to do a talk because three people backed out the week before the conference. Even when speakers don’t cancel, you have to hope they’re good and that their flights don’t get cancelled. You hope the food shows up on time and that it’s not too hot or too cold. You basically just sit there with all your muscles tensed the entire time. When each day is done, we’re exhausted just from being there. Each Brooklyn Beta costs me three to five years of life—it’s like a minor felony.

When you developed the idea for Brooklyn Beta, what was your goal?

Cameron: The main thing was to bring designers and developers together—our dream was that it would be 50/50. The “make something you love” thing was in the mix from the beginning. We just thought people would be happier and the world would be a better place—all these kinds of cheesy ideas—if designers and developers would work together to make something they gave a shit about. We also wanted to do something that felt more like a family reunion or party than a conference.

Chris: Brooklyn Beta is really the coming together of our personalities. I wanted to push people to do more with their talent. With the talent we have and the opportunities we’re presented with, we’re falling short of our potential. Cameron brought a startup, business-oriented approach that gave it more teeth. Because of that, the message of Brooklyn Beta as people have received it feels meatier and more actionable.

Most of my peers over the last decade have been developers who say they don’t know any good designers. Once I started to get to know a lot of good designers, I heard the opposite—they don’t know any good developers. There are lots of friendly, talented people in both camps and we thought they should get to know each other.

Cameron: I try to think about why people like the conference so much. We don’t really know and we try not to look at it too hard—we don’t want to jinx it. Instead, we change as little as possible from year to year while still trying to keep things exciting. We rely heavily on our friends, especially Jessi and Creighton from Workshop and Martha and Casson. There is an attention to detail that pervades Brooklyn Beta and, these days, it has much more to do with them than us. (laughing)

Chris: Yeah, they are incredible.

Cameron: We also get help from other studiomates, like Jen, and past attendees, too. All this collective effort is why folks probably like it and why Brooklyn Beta is way better known than Fictive Kin or anyone on our team, except maybe Simon Collison, who has animals on his website and says smart things in a British accent.

You guys have done a lot of things as adults, but what were you like growing up? Was creativity a part of your childhoods?

Chris: It was definitely part of mine. My mom is really artsy and crafty, so teachers were excited to have me in class because they knew she’d be very involved and lead fun projects. I was really into drawing and painting and stuff like that.

In high school, I got really into math and was good at it, so I was put on the path of computer science and engineering, which was awesome, but I ended up becoming a developer without really making a deliberate decision about what I wanted to be. There will always be part of me that wants to be creative, and because of my background, I think I have a deeper appreciation for design than most developers.

That’s really interesting.

Cameron to Chris: I didn’t know that about you.

Chris to Cameron: Yeah, I have some paintings I can show you.

Tina to Cameron: And what about you?

Cameron: I’m an older brother and the oldest of all my cousins, so I applied creativity to ways to be a bully—

(all laughing maniacally)

I think that mischief and nerdery were more the core tenets of my youth than creativity. My parents weren’t traditionally creative, but listened to a lot of music, so music and singing were a big part of growing up. I did draw, but it wasn’t anything standout. I didn’t feel especially creative.

Business stuff was there early on, though. I used to like stocks a lot, which was so lame. I used to read all kinds of books on investing and would look at the stock page in the paper every day, because that’s what my grandpa—who was a badass WWII paratrooper—would do. Once he retired from the army, he got into investing in the stock market. His timing was really good because it was the first Internet bubble, so he made bank before it popped.

He’s also indirectly tied to how I stopped liking investing. When he made a bunch of money, he gave everybody in the family $10,000 because that was the exempt amount under the gift tax and he figured it was better that the family get it than the government. Once I had all that money, I decided it was time to put my stock skills to the test. I saw somewhere that Philip Morris owned Kraft and thought I’d buy that because it was super cheap. I thought maybe that was because everyone was hating on cigarettes, but nobody hates cheese. My aunt told me, “Don’t buy that. Haven’t you heard about science? You should buy stock in Nokia and all of these companies.” I can’t remember the names of all of them, but basically, she convinced me to buy stock in five different technology companies and my money went from $10,000 to $600 in four months. Meanwhile, Philip Morris went through the roof. I’m not entirely sure what lesson I learned there, but I haven’t bought a stock since then.

That’s a great story. How old were you?

Cameron: I was maybe 12 or 13.

Did either of you have an “aha” moment when you decided what you wanted to do?

Chris: I don’t know that I’ve ever had an “aha” moment, but I remember a pretty important moment during a trip to Iceland with my friends Andrei and Helgi. We were standing on top of Sjónarsker, where the view was just incredible, and I had just told them I was leaving my former company. They asked what I was doing next. I didn’t really know, but I did have an answer: “Good people. Good work.” That’s been a guiding principle for me ever since.

Cameron: A lot of people struggle with figuring out what they want to do, but probably the luckiest thing to happen to me is that I’ve always kind of known. I’ve just been honing it over time. I started out vaguely interested in business without really knowing what that was. I majored in economics in college because I thought that was what business was, but it turns out it’s more than just diagonal lines. By the time I was a sophomore or junior, though, I had gotten to the core vision for what Fictive Kin is now and I knew a lot of the people I wanted to do it with. It makes me pretty proud to have a lot of them working with us now.

Did either of you have mentors?

Chris: The guy who gave me my first job after university hired me because we went to the same high school. He just assumed I was a badass and told everyone that I was. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was hired into a pretty senior position with all sorts of expectations attached to it. My boss scared the shit out of me on a daily basis with what he expected me to do.

I don’t know if that counts as mentorship, but I spent my first year there being terrified. I had a computer science background, which gave me a good foundation, but it wasn’t helping me get the job done. I had to fast-track it to learn the practical skills. I spent every night at Borders figuring out what book I needed to buy and consume that night. I had a computer lab with about a dozen computers set up in my apartment so I could learn about managing servers, networking, firewalls, proxies, and stuff like that. At some point during that job, it felt like a switch was flipped, and I thought, “Oh, I feel extremely competent now. This is awesome!”

I think I owe a lot to that early experience and to my first boss, Randy Tremaine. He probably never thought of himself as a mentor to me, but he was.

Cameron: We need to circle back to eDonkey and Facebook later. I’m remembering some stories that Chris is leaving out.

Should we cover those now?

Cameron: Yeah, let’s tell some stories. Start with eDonkey.

Chris: Okay. My sister went to school in New York and lived here after that, so I grew to love NY a lot.

Where did you grow up?

Chris: In Tennessee. Once my wife and I decided to move to NY, that’s exactly what we did. We didn’t have jobs or an apartment here, but in a single day, we found an apartment and both got jobs. I’ll spare you the details, but that’s another crazy story. It was a very hectic day.

I got a job with eDonkey. The team was small and consisted of the founder, another developer who was also named Chris, a business guy, and me; I handled all the server stuff. Only three of us were building the product and we didn’t have a lot of money, so I bought all our hardware from eBay, and I managed our infrastructure.

What’s cool about eDonkey is that it’s probably still the largest file-sharing service. At one time, we supposedly accounted for nearly half of all traffic on the Internet. This was back when Windows viruses and worms were very common and people would decode them to find out what they did. There was a particular worm that was designed to attack our site on a specific date, so all these infected computers were going to be part of a global, organized assault.

As the guy responsible for all the server stuff, I was pretty scared. This was going to be massive. I spent a week preparing, knowing that I probably had no shot. I did some clever stuff, but the worm totally won; our site never went down, but it was basically unreachable for most of the day. We had a 100 Mb connection, which was pretty big back then, and the incoming traffic alone consumed all our bandwidth.

Cameron: I just like that four people were in charge of a very significant portion of all Internet traffic and were doing it by the seat of their pants with shit from eBay. Also, as part of the ongoing Chris-Cameron life braid, one of his co-workers at eDonkey went to business school with me.

“Have patience, because it’s a long journey—don’t be too eager to get to the finish line…don’t define what success means the way you are now…” / Chris

So, there’s a Facebook story, too?

Chris: Yeah.

Cameron: It’s more a story about a bad decision. Have you heard of Ning?

No.

Cameron: Have you heard of Facebook?

Yes.

Cameron: That’s my point.

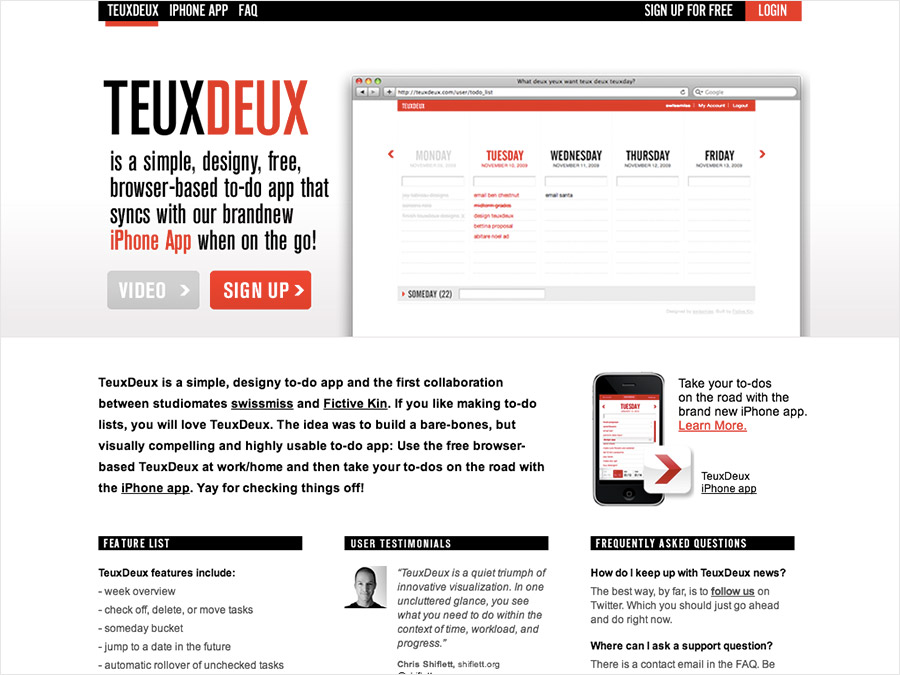

Chris: After eDonkey, I went into consulting on my own as a freelancer. I got an email from this guy named Marc Andreessen. I’m a computer science graduate and we’re taught about him because he created Netscape, which was responsible for things like cookies, SSL, JavaScript, images—a lot of important stuff on the web. He wanted me to help with his new thing. I kinda thought that someone was messing with me and that a friend sent the email, but it was legit. I flew out to California, had dinner with him, and learned about his new thing, which went on to become Ning.

Meanwhile, someone else reached out from The Facebook, which I thought was an awkward name. Both companies were in what they thought was a unique industry—social networking. Since they were competitors, I had to make a choice. Needless to say, I did not choose The Facebook, a decision that probably cost me a fortune. Literally.

Cameron to Chris: It makes sense that—in the moment—you would choose Marc Andreessen.

Chris: Also, The Facebook sounds super lame. I didn’t think about dropping the “The”—that changes the whole ballgame. If they were Facebook.com, I might have made a different decision.

(all laughing)

Tina to Cameron: Back to the mentor question. Did you have any mentors?

Cameron: I’ve never had too many older-than-me mentors. Instead, at pretty much every important phase of my life, I’ve had peers who were both friends and heroes. These folks, through their example, have helped me to be less shitty. In high school, I met some friends who were all more driven than me and because of them, I became more academically driven; if it wasn’t for them, I don’t think I would have gone to the college I attended.

Then, in college, I met Tyler, Evan, and Frank—some of the folks who work with us now—and once again, I was saved from suckery by nice people. In grad school, I had a professor named Andy Rachleff. We didn’t really have a formal mentor-mentee relationship; he just said smart things all the time and I remembered what he said.

When I first moved to New York, Chris and Tina were major role models. It’s not that I’ve learned skills as much as I’ve learned life stuff from them. For example, Tina is so positive and generous and she lives it on a daily basis. When you watch somebody live so positively and realize how much you enjoy being around it, it’s hard to ignore. I don’t know if that’s mentoring, but I’m cooler because of them.

Has there been a point in either of your lives when you took a big risk to move forward?

(Chris and Cameron both laughing)

Chris: As a company and individually, we take on so much risk that it’s kind of a bummer to talk about.

So, if people want a detailed answer to that, they’re going to have to take you both out for a few drinks?

Chris: Yes. And tell them to ask us about 83(b)s.

What is an 83(b)?

Cameron: Ugh. I guess we can talk about this. We both got burned pretty badly by it, so it’s not a fun topic. The way it works is this—when you receive equity, you have 30 days to figure out what an 83(b) is, or you’re gonna lose a lot of money.

If you file an 83(b), any money you make from your equity down the road gets taxed as capital gains, which is how all the rich people avoid paying lots of taxes. If you don’t file an 83(b) or don’t file it on time, any money you make on your equity gets taxed as regular income, which is a lot more money and a lot less awesome.

For startups, it’s really bad because there’s so much risk already. If you do manage to finally make some money, you stand to lose a lot of it to taxes. You can risk everything for years, but if you fail to file an 83(b) at the very, very beginning, there’s nothing you can do.

Chris: As our lawyer likes to say, this leads to “irreparable, disastrous tax consequences.”

Cameron: So, yeah. We both got some of that.

That’s important to know.

Cameron: You have 30 days from the moment you get equity to file an 83(b). You should put that in bold. Also, you should link to Yokum’s post on this. It probably gets more of the details right, since he’s a lawyer and all.

Alright, thanks for the tax advice, guys. Moving on, are your friends and family supportive of what you do?

Cameron: My parents are generally confused about what I do.

Did they contribute something for your badge at Brooklyn Beta?

Cameron: Yeah. My dad was trying to be funny and, in my opinion, he was. He said something like, “Cameron is a troubled, cigar-chomping genius.” I think sometimes my parents just ignore my decisions and think, “He seems to be making bizarre, aggressive decisions and if we don’t look at them, we’ll be happier.”

And what about you, Chris?

Chris: My dad was also an entrepreneur, so I’ve been able to talk to him about a lot of the tough stuff I go through, which has been helpful. My wife is also very supportive and my daughter, without knowing it, is supportive. None of this would be possible without them.

Do you guys feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourselves?

Chris: I think we both do. This is the message of Brooklyn Beta, and it’s been cool to see past interviews mention the conference. I think our attitude around this is similar to what I was saying before. You can be too aggressive in holding yourself to the standard that if you’re not saving the world, you’re not doing something good enough; I don’t think that’s a fair standard to hold yourself to. On the flip side of that, you should be doing something that is creating value of some sort and is meaningful on your own terms.

Cameron: This guy talks like butterscotch; I love it. I’m gonna start calling him Butterscotch.

Tina to Cameron: Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something?

Cameron: So, Butterscotch covered the Brooklyn Beta stuff. I didn’t realize—until he said all that—that it’s probably the best public expression of our internal guiding philosophy. As for the upcoming Fictive Kin stuff—Chris and I talked about this on the way over here. We said, “Wouldn’t it be cool to get interviewed by TGD in a couple years after we’ve done something?”

Chris: We feel like we’ll have a better story to tell.

But that’s what this is all about. Our readers like knowing that things are in process and that people don’t have everything figured out.

Cameron: Welp, they’re in luck because, one, we don’t have it all figured out, and two, we’re big time in process.

(all laughing)

So yeah, I feel a responsibility to contribute. I think it even goes past responsibility and into guilt. I’ve had a lot of good breaks and now I’m in this place where I have some freedom to work on the projects I care about and work with a team that can actually make something big happen. Not sure how I’d feel about myself if I didn’t do something pretty important with that setup.

“If you decide to run a couple of plays from outside of the book, then you should expect people to question your decisions…You’re stepping away from the rest of the world and you have to rely on yourself and others like you.” / Cameron

Are you satisfied creatively?

Chris: I think my answer is no. I don’t think I could be satisfied creatively and still feel as driven as I feel.

Cameron: I’m going to say no, too. I’d like to make more things on a day-to-day basis. I end up doing a lot more admin work—which is necessary, but not as fun or satisfying.

That said, what are you guys interested in doing or exploring in the next 5 to 10 years?

Chris: I don’t know if it’s as long-term as that, but I don’t think we’re leading by example as much as we want to be. I think we have a good mission with the conference and Fictive Kin, but it’s not like we’re the example that people use to justify that mission. We’re not there yet and getting to that point would feel really good. It’s definitely doable within that time frame and if we don’t make it happen within five years, then I think we’ve misunderstood ourselves and our potential.

Cameron: Yeah, I agree. What I’d really like is if in 5 to 10 years, we have the same people around and we’ve shipped products that make the world a better place and that people like using. I think the best thing we’ve done so far is to bring together the team we have and get started on a pretty cool culture. Now, we’re poised to do something pretty special. I feel like we’re this big ball of potential energy and I’m hoping to see what it looks like when we make that kinetic.

Well, now we have this documented and we’ll get to see what happens in the next five years.

Cameron: If things go right, it’ll be one hell of an interview. If not, then five years from now, I’m gonna just move to Cuba and live on the beach like in those Corona commercials. You’ll have to find me there.

This is a fun one. If you could give advice to a young person starting out, what would you say to them?

Cameron: I can go first. Old Man Cameron has opinions.

Chris: Also, “Old Man Cameron” is 30.

Cameron: Yeah. He’s got me there.

Here’s my advice. Track down a little bit of self-awareness. If you’re in your early 20s, you almost certainly don’t know very much about design or business or even life. You don’t know anything about anything. On the plus side, you’re not alone. People older than you—myself included—don’t know much about anything either. But, the older people get, the more they’re willing to recognize how little they know.

The “young people starting out” who I’ve encountered have almost no awareness of how little value they provide, so they turn their noses up at jobs that they really shouldn’t. They want to follow their dreams, so any job that isn’t their dream job—they’re too damned good for it. Work, like anything else of real value, takes time and patience.

Chris: I know when I was young, my idea of what it meant to be successful wasn’t really mine. If I could somehow distill what I think it means to be successful into words, I’d share that.

Have patience, because it’s a long journey—don’t be too eager to get to the finish line. Also, don’t define what success means the way you are now, because you’re young, and your definition of success is probably not your own.

If someone could have told me that when I was younger, it would have been helpful. Whether you’re chasing good grades or the right university or the right job, there’s a certain path that this false notion of success can lead you down and it’s probably not going to make you feel very satisfied, happy, or even successful—but you think that’s what you should be doing. If you can figure out how you would define success in the future and feed that to yourself earlier, I think it would make a big difference.

Cameron: Dammit. Now I want to say something nice like Chris.

I’ll add that if you want to do something unique, it’s important to know about the life playbook. It’s this playbook that most everyone in the world seems to be working from. It has everything you can do that will be looked upon with approval by other people: Going to college, getting a steady job, watching Grey’s Anatomy. If you decide to run a couple of plays from outside of the book, then you should expect people to question your decisions and generally not be too supportive. That’s what makes it so difficult to do things like go freelance, start a company, become a writer, and shit like that. You’re stepping away from the rest of the world and you have to rely on yourself and others like you.

Something a little more insidious about the whole thing is that I kind of think people want you to fail when you go off book. If you fail, they can say, “See? Look what happens when you stray from the playbook! Glad I didn’t do that.” But, if you succeed, it forces them to look at themselves a bit more closely and ask why they didn’t try the same thing.

How does living in New York impact your creativity?

Chris: New York is really nice because it’s very different from where I grew up. It’s a big city with a lot of people and I grew up in a small town with very few people. Being here exposes me to more people and more stuff. Specifically, NY is good about bringing together all kinds of different people from all kinds of different backgrounds, which is helpful for work. We’re creating apps for people, so the more types of people we can understand and empathize with, the better we’ll be at our jobs.

Also, the big lights inspire me.

Cameron: When I was in San Francisco, everyone was in startups. I’d go to a coffee shop and everyone had a business plan. When I was in LA, it was the same scene, but everyone had a script instead of a business plan. Here, I can show up at a house party and everyone does something different. I can say something like, “Hey! I just saw Massimo Vignelli!” They’d be like, “Who?,” and then say, “Hey! I just saw Fashion McFashionson!,” and I’d be like, “Who?” If you want to think and learn and create things, it’s fun to be around that kind of variety.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Chris: I think so. That’s what brought me to NY and to Studiomates.

Cameron: It’s super important to be around nice people who give a shit and don’t think they’re the shit.

We’re gonna skip the typical day question.

Chris: Good, because we don’t have a typical day.

What albums are you guys listening to right now?

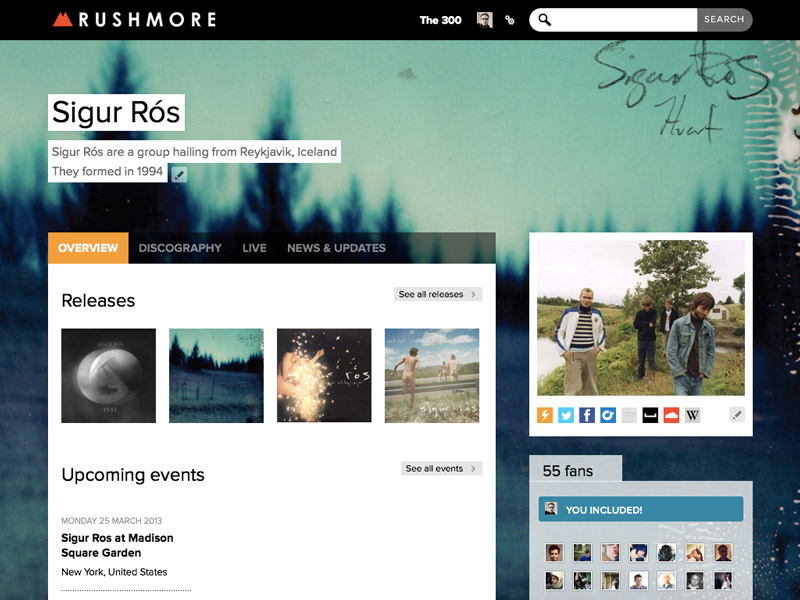

Chris: Since I’m doing a lot of focused work this month, I’ve gone back to some old favorites like Ratatat, Sigur Rós, and Girl Talk. If I had to pick a single album, I’d probably go with something by Indigo Girls, like Swamp Ophelia or Become You.

Cameron: Anything by Nicolas Jaar or LCD Soundsystem. Also, Fergie—one of our spiritual and business advisors—put out her seminal album, The Dutchess, in 2006, and we’ve had that on repeat at Fictive Kin ever since.

Do you have favorites when it comes to TV shows or movies?

Chris: I really like Samurai Champloo. Cameron introduced me to it and we watched the entire series during much of our early work and planning together. I’m currently making my way through Cowboy Beebop, which is a lot of fun. Other shows I’ve enjoyed include Battlestar Galactica, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, Firefly, The IT Crowd, and BBC stuff like Robin Hood, Merlin, and Sherlock.

For movies—I love movies, so there are too many to remember. We’re working on an app that will help with this sort of thing.

Cameron: Right now, my favorite movie is Sullivan’s Travels and my favorite TV show is Adventure Time.

What are your favorite books?

Cameron: I can’t do it; I can’t pick one. Lately, I’ve been reading and enjoying E.B. White, Hemingway, and Vonnegut. Maybe The Count of Monte Cristo is my favorite? That is one hot fudge brownie sundae of a book.

Chris: If I let nostalgia influence my answer, I’d go with something like The Hobbit or The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

More recently, I thoroughly enjoyed Born to Run. I stumbled upon the barefoot running movement, and this book, by accident. I play soccer regularly, but I’ve never liked running. As an experiment, I set out to find a running shoe that was built more like a soccer shoe, which eventually brought me to Vivobarefoot—not to be confused with Vibram Five Fingers. They had a copy of Born to Run at the Vivobarefoot store in SoHo and I remembered my wife had also told me about it. She’s finished more than a dozen marathons, so it wasn’t surprising that she liked a book about running. I walked out of the store with a copy of the book and a pair of Aquas; the combination of the two inspired me to get back into running. Within a month, I was running up to 20 miles at a time and actually enjoying it.

Currently, I’m reading a book about the neuroscience of magic called Sleights of Mind, which is fascinating. Next up is Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Favorite food?

Chris: I love good pizza, especially from Lucali and Grimaldi’s; good burgers from 282 and Shake Shack; and good sushi from Gen and Geido. All of these are NY places, but my favorite food is probably the Reuben sandwich from Hofbrauhaus in Gatlinburg, TN. It’s just about the last place you’d expect to find one of the world’s best sandwiches, but I’ve yet to find its equal.

Cameron: Four to six slices of pepperoni pizza from Sam’s, Lucali, Grimaldi’s, or Lombardi’s. There’s a formula.

What kind of legacy do you each hope to leave?

Cameron: I don’t think I want there to be a Cameron legacy, or even a Fictive Kin legacy. What would be really cool is impact minus legacy. Legacy feels pretty self-important, and I don’t know how to get around that. I want to do stuff that stays around and has an impact—stuff that makes me feel like there was some meaning in the work I did, but it doesn’t have to be about Cameron or Fictive Kin. Part of me thinks it’d be even cooler if no one knew we had a hand in it.

Chris: I think a big aspect of anyone’s legacy is their kids. You live on through them because you teach them and bring them up and they have your DNA, literally and figuratively. That feels pretty important. It’s a big part of what makes us human.

On the work front, I just went to a conference called Build, where I heard Ethan Marcotte talk about the guy who is responsible for the grid system in New York—I forget his name, which is kind of the point. The fact that you could do something that has such a profound impact on so many people and not be remembered for having done it is really appealing. I’ve talked to Cameron a lot about my past and how I like the role of being in the background—driving from the back seat. I’d like to be part of a group of people who do great things without me being the person recognized for it. That’s not due to having an insecurity around receiving credit; I just think that the moment you receive credit, you’ve changed the ballgame in a way that’s probably not what you want.

Cameron: That’s also why doing this interview is hard for us. The stuff we do is the result of so many great folks—and Evan—working together, it feels kinda weird to be the ones talking about it. I hope they like this interview. Or even read it. (laughing)

“What would be really cool is impact minus legacy. Legacy feels pretty self-important, and I don’t know how to get around that.” / Cameron