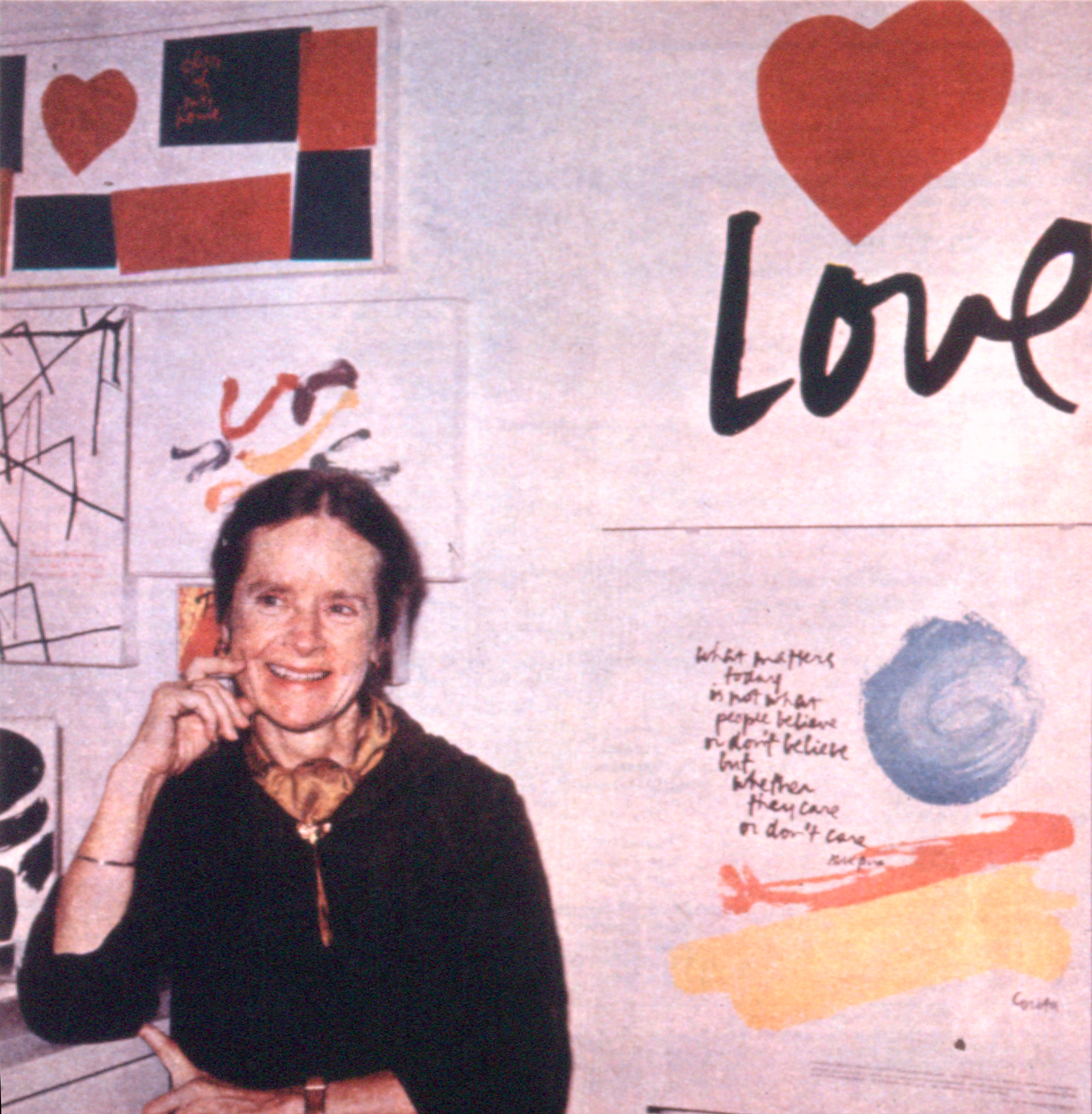

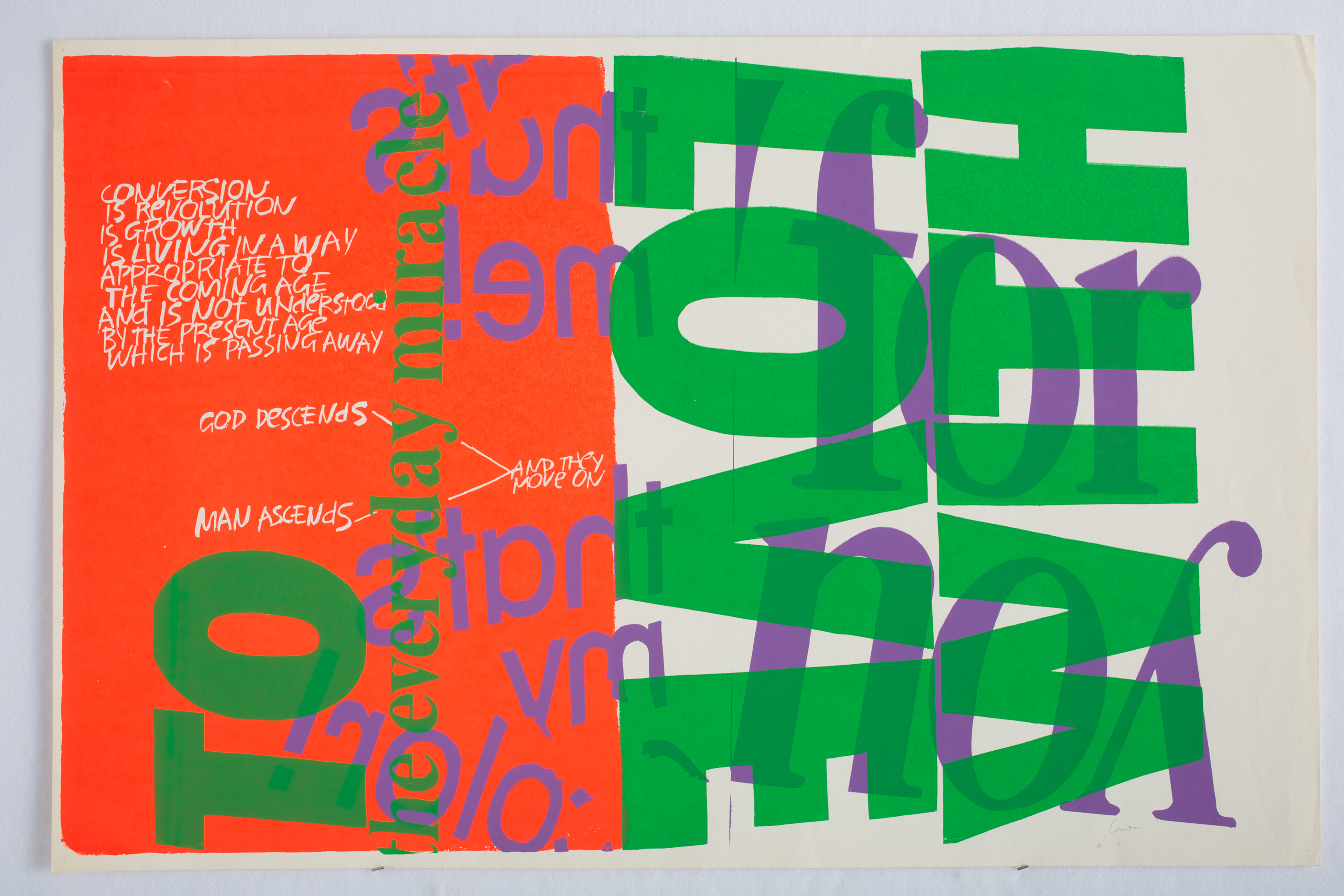

“Sometimes you can take the whole of the world in, and sometimes you need a small piece to take in,” says Sister Mary Corita, to a group of art students in footage filmed during one of the classes she taught at L.A.’s Immaculate Heart College in the 1960s. She advises them to gaze through a one-by-one-inch square cut into a piece of cardboard before setting them loose at Mark C. Bloome’s, a colorful car and tire shop in Beverly Hills. “I think that’s really what a work of art is,” she continues. “It’s a small piece that you can digest which gives you a kind of idea of the richness that is in the whole.” Corita Kent called these cardboard cut-outs “finders,” and this exercise is just one indelible part of her legacy, which is relevant as ever, and continues to inspire.

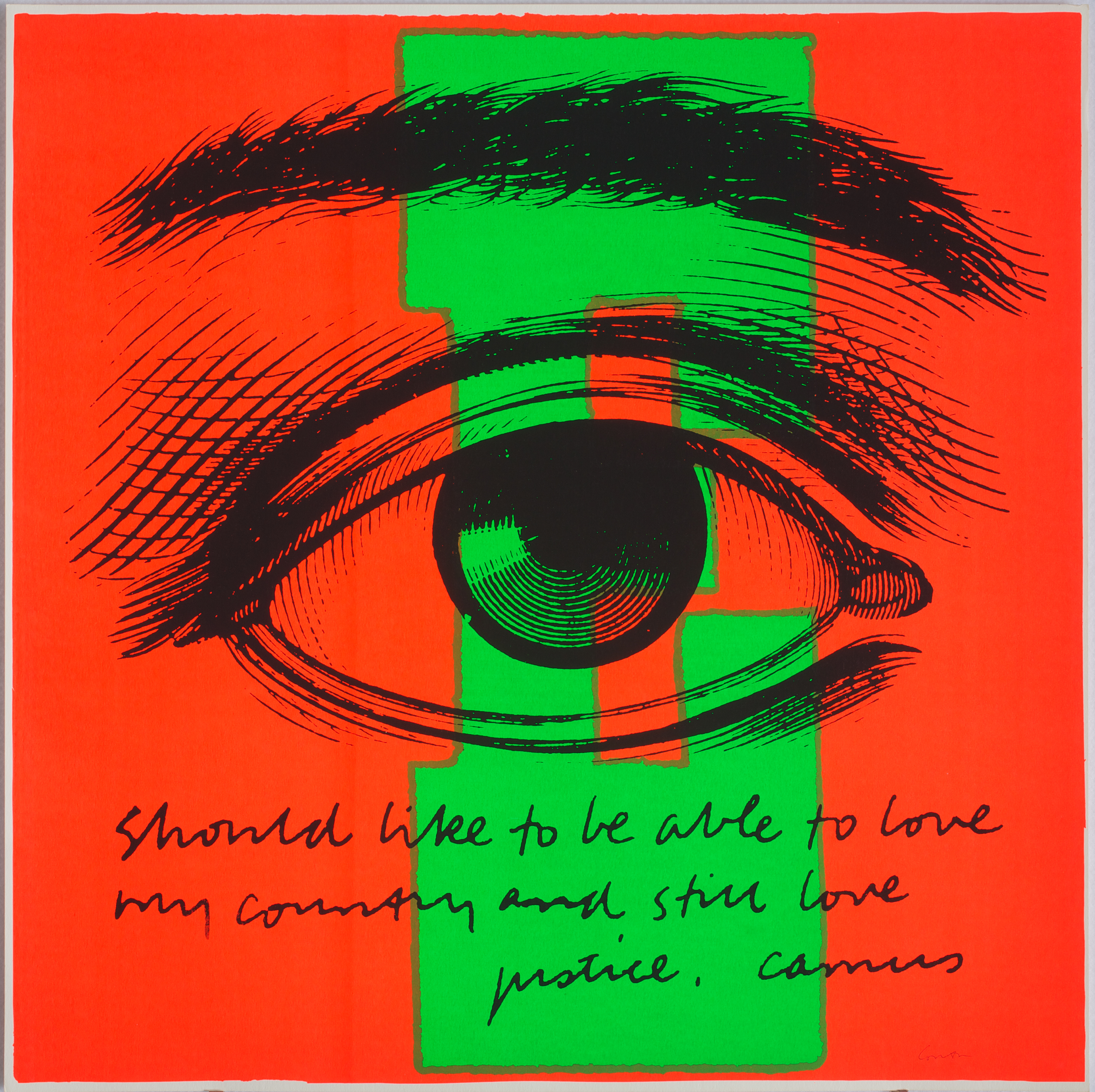

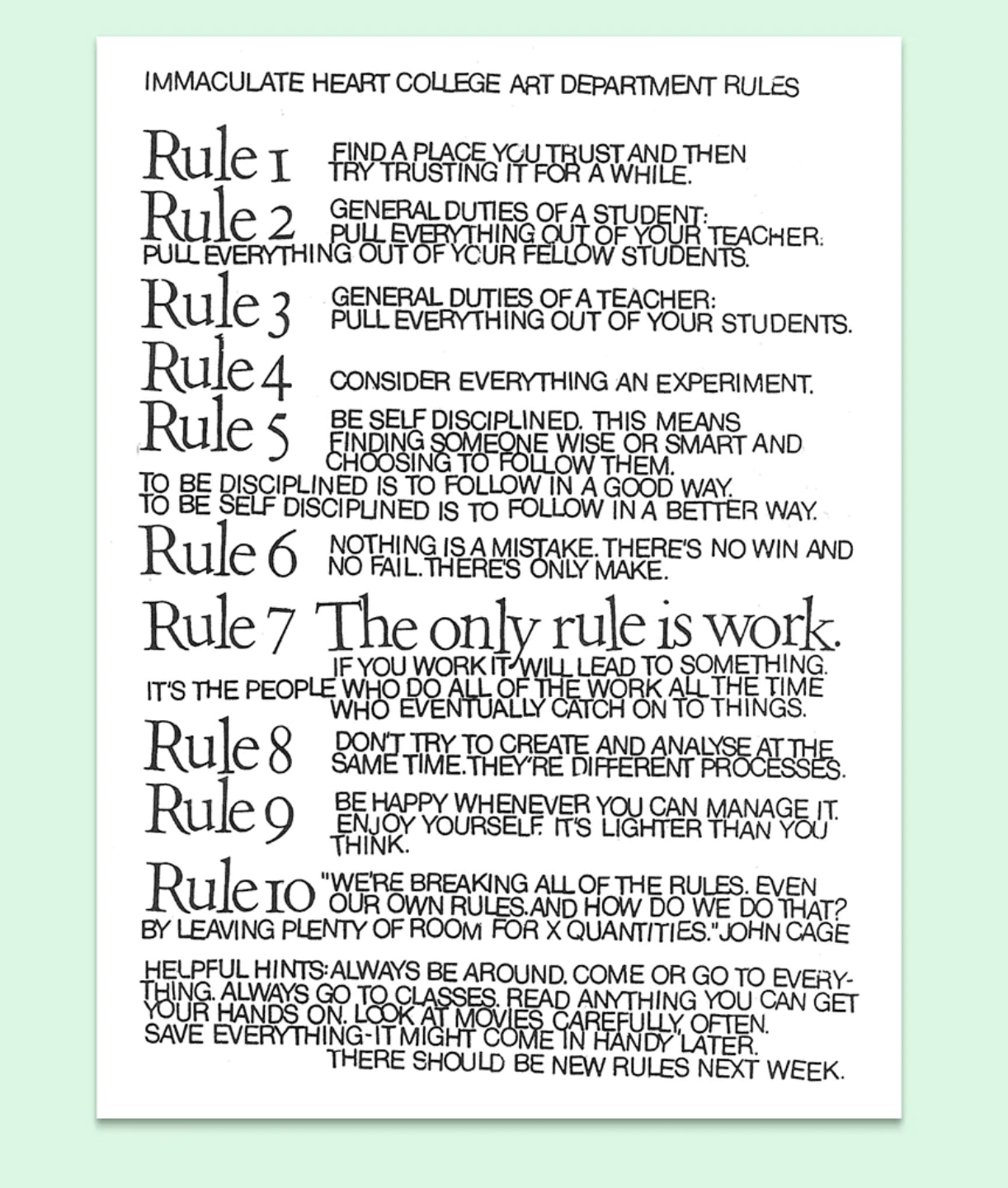

As a devout Catholic nun, Kent was a seemingly unlikely force in the American pop art movement of the ’60s, but her vivid screen prints, which married aesthetics and activism, along with her progressive teachings that centered social practice, endeared her to the high-brow art world and general public alike. (Though the same cannot be said for the local conservative Catholic leaders at the time.) Kent continued pushing boundaries and making waves until she took a dispensation from vows, effectively leaving her formal life as a nun in 1968. After that she moved to Boston, and continued making art until she died from cancer in 1986 at the age of 67. The continued proliferation of her 10 rules, created with her students for the Immaculate Heart art department, attest to the endurance of Corita’s art and teachings. “Consider everything an experiment,” states rule number 4. And that’s what this is as well—a conversation about Corita’s ongoing relevance and influence with Nellie Scott, director of the Corita Art Center; L. Frank, a Tongva-Ajachmem artist and one of Corita’s former students; and Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo, an artist and educator deeply influenced by Corita’s work.

To get us started, can you each introduce yourself and tell a bit about your work?

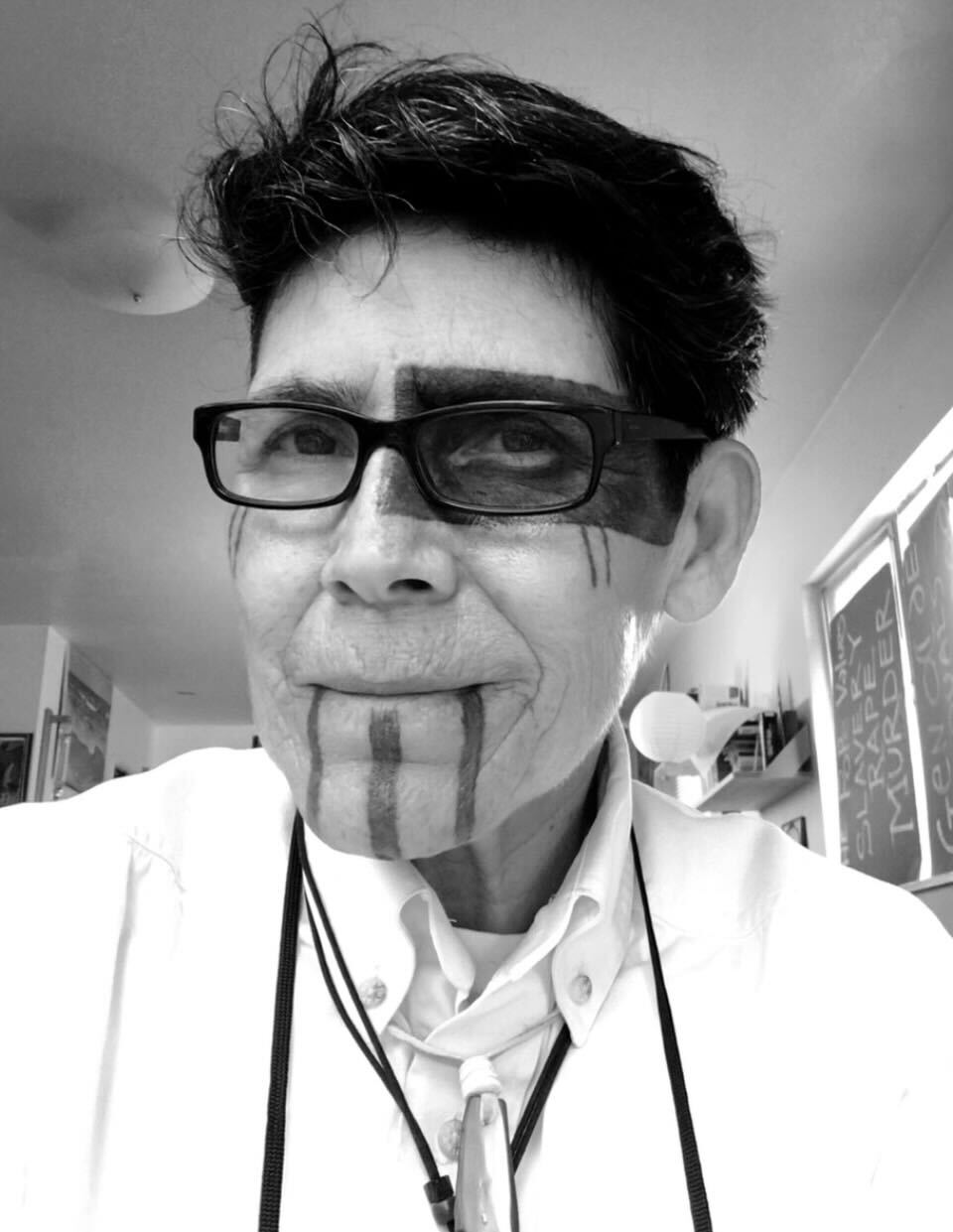

L. Frank: I’ll give you the official hello: irresponsible artist, responsible activist. When I was about nine, I started shooting photos. Then I started drawing. Now I’m teaching myself animation and Illustrator. I’m also teaching myself how to edit film. I really like casting silver, I really love painting. The reason that I do a lot of different things is because my people of Los Angeles—the originals—we are considered extinct. So my focus is for us to not be extinct. And the only way to make that happen is to become visible. I made the first stone bowl by someone in my tribe in 200 years because I found out, “Oh, holy heck, we made stone bowls. I guess I better make one.” So I became a stone worker. Then I worked with wood. It’s piecing back together a culture in order to see who we are. I spend a lot of time doing research and then I just make and make and make some more.

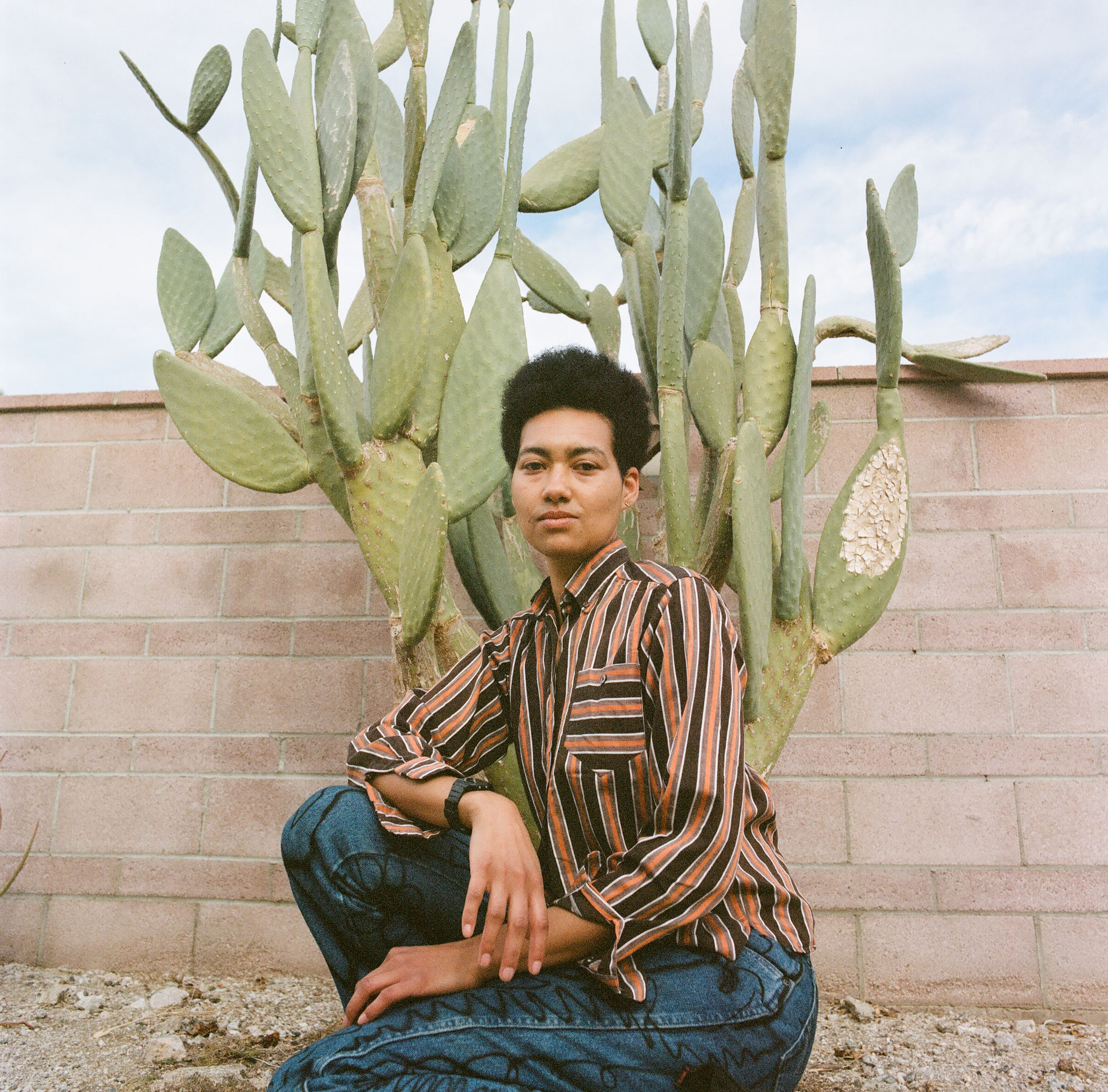

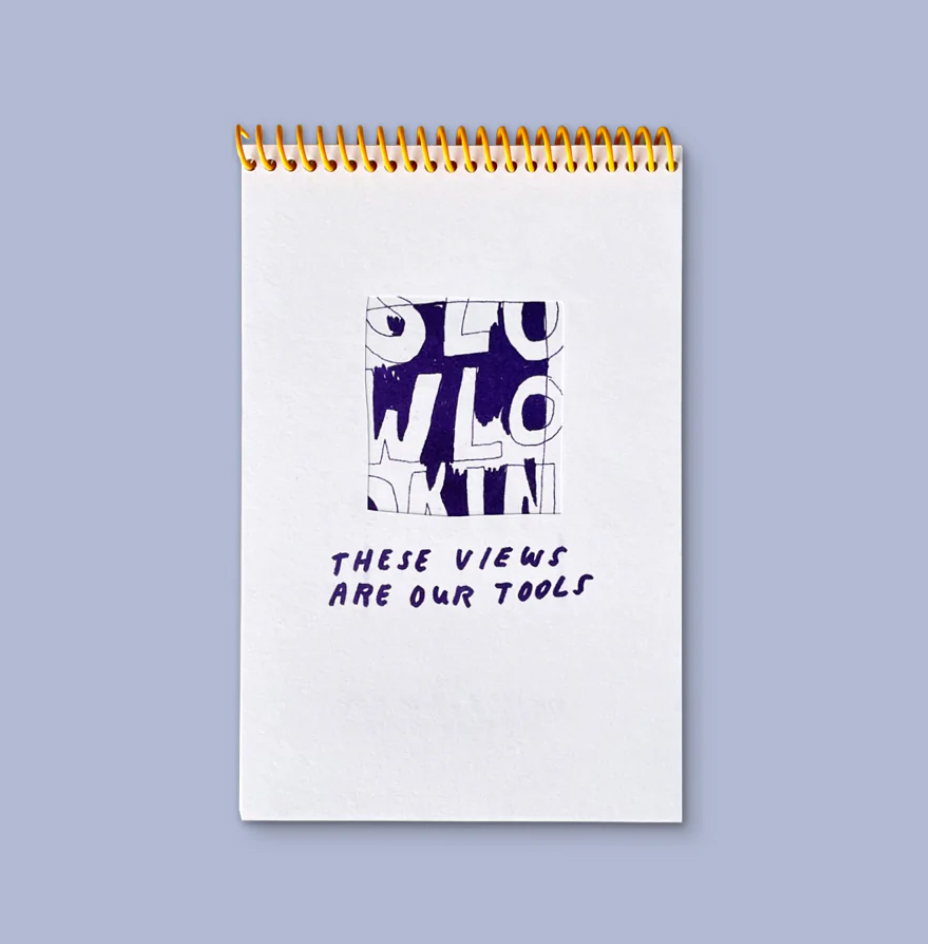

Lukaza: As an artist and educator and storyteller and curator, my work prioritizes the archiving and telling of black and indigenous queer or trans and gender-nonconforming folks of color in my own world. I make work in a collective model. I always think about this web of stories, and this web of holding each other, and this collective way of surviving, and thus making, in the world. The medium is discovered as the collaborators are brought in and the stories that need to be centered are figured out. With roots in printmaking, whatever medium I choose I often think about the way that I make a print. I use paint, I’ve made murals on walls and on glass, I’ve made protest banners and spaces to be together. And all of those feel like these imprints or shared ways of collecting and thinking about, How do we survive? How do our people survive and thrive and sustain each other?

Nellie: As the director at the Corita Art Center, one of my favorite parts of the position is either introducing people to Corita, who are like, “How did I not know this?” Or meeting those people that very much knew who she was, that are like, “Corita was the cat’s meow.” What makes this organization so unique, especially in the landscape of artist’s estate, is that Corita left hers to the Immaculate Heart Community for the benefit of people. This was her family. Over time, they recognized how important their role was in keeping that memory alive and they founded the Corita Art Center in ’97. My time here has been building a team of really incredible professionals. And asking, How do we lengthen the table to bring more people to it? How do we keep passing that torch and that legacy and invite people in, in a very structured way? It feels like there’s a blossoming happening. When I think about the future of the Corita Art Center, we have an opportunity to build an institution, this type of model, that doesn’t exist yet.

What’s your Corita origin story?

L: Well, I had no idea who she was [laughs], I was just going through the late ’60s. But a friend of mine from high school went to Immaculate Heart, and I went to a party in the dorms, which were actually at the convent. We used to jump up and down and make the elevator stick in between floors—the fire department would come get us out, and the nuns would be mad. But that was my introduction to Corita, I mean when I turned around and looked. I realized that this was the place I needed to be, my brain fit this place, it fit this person. Little did I know that I would fall madly in love with printmaking.

Lukaza: I learned about Corita when I was in high school, in a printmaking class. I grew into myself as an artist through printmaking and that called me to Corita’s work—print as a collaboration between social justice and activism and a more visual practice of understanding the world. I immediately felt so seen within her color choice and graphics and ways of reflecting the world. And as an artist who also identifies as an educator, and a story collector and listener, it also hit me in the heart to learn about the breadth of Corita’s practice. Not only was she making these prints that were such reflections of this world and hopes, she also was an educator and was learning with her students.

Nellie: Like every single person that’s introduced to her, I’m absolutely enchanted by her. The heart of Corita was something I was really drawn to. We all have an educator that we can point to in our lives, you can feel their hand on your shoulder saying, “You can do this, anything is possible.” [For me,] I really credit Harrell Fletcher, who is a social practice artist [I learned from at Portland State University]. The idea of challenging the hierarchy of knowledge, that we are all students and we are all educators and the way that we sink our teeth into the idea of collective community and experience, that’s something I carried with me, especially as I went into the very commercial side of the art world, moving to New York.

I was the first exhibition coordinator for Nathan Sawaya’s first show of sculptures. What struck me when I was working with him on that was the guest experience. People who had never been into a museum before were lined up because it was a medium they were familiar with. I loved that—the shared experience of, “This isn’t a white wall experience, let’s make this open and accessible.” Through that tour I had the opportunity to build out curriculum. That spawned this love for nonprofit work, but also just thinking of art from a very mass perspective. I felt really drawn to Corita and the opportunity to keep pulling on the thread around message and the common good—this idea of creating a new type of community and collective practice, and finding gratitude.

Nellie, can you talk about the responsibility of shepherding Corita Kent’s legacy, looking back on a body of work, but also what you’ve called the embedded call to action in her work?

Nellie: It’s important to think of her legacy as a living legacy—she’s a real human. She’s not this monolith, she’s not a saint, either. It felt really important that we’re representing her as a whole person, as an artist, as an educator. Her work is the foundation. That’s the platform for us to be a champion in the work that’s happening today and to keep it current. Our North Star has always been education, because to reach these goals of social justice and of messaging that are so profound in Corita’s artwork, you have to center education. And through that, we center artist-educators. When we think of our mission, it feels like engaging with her, but without centering her. If we’re talking all about Corita every single day, then we would be missing the opportunity to lift up the voices that are inspired by this type of social practice, and the dialogue that can happen between artwork that happened 50 years ago and artists today.

“Our North Star has always been education, because to reach these goals of social justice and of messaging that are so profound in Corita’s artwork, you have to center education. And through that, we center artist-educators.”

Lukaza and L., in the context of Corita Kent’s work, where does that balance and that tension between artist and activist live in your own practice?

L: One of the callings of artists is to be a mirror to what’s happening in the world. I always felt that way, but reaching Immaculate Heart and seeing what Corita was doing—one day, we just picked a lot of flowers and put them in the hands of all the statues of all the women on campus, and that was even an activist act. Everything was. But softly, not, “I am an activist.” It thrilled the hell out of me. It meant that I didn’t have to be abrasive in order to be an activist. In the ’60s, there were a lot of things going on politically. I grew up watching dogs and water hoses being set on people, and soldiers dying in front of my eyes. And here was this beacon of a sane way to approach anything heavy—a really gentle, amusing, thoughtful way. And that was the kind of activism I was attracted to. I’m [part of] this large organization that’s helping save the coastlines in L.A. and Orange County. The person who started it is a lawyer, and I said, “You’re gonna need to write a letter.” And she says, “Oh no, you just make a piece of art. Your art has cleared the way more than any of my letters.” That’s the activism.

Lukaza: I think of art and activism as mirrors to each other too, they are each other and need each other. I’ve done a lot of prison abolition work and work with critical resistance. I remember a talk between Angela Davis and Ruthie Wilson Gilmore about the importance of art in movements and how throughout every campaign and every movement that they do, artists are always at the table. I think that there’s a different lens, a different way of digesting this complicated, beautiful, hard, terrible world we live in through artists and through art making. In many ways activists are thinking about the future differently, cropping the frame differently in the ways that artists are.

Nellie, how does Corita Kent’s religious background factor into her legacy, especially in our ever-more secular culture?

Nellie: We talk really openly about her spirituality. From an art historical perspective, it could be argued that all work is religious, right? [laughs] But with Corita, there’s an intersection of faith and social justice and art and activism—it’s all rolled up in one. And you can’t unweave her core spirituality because it’s felt in her work. I’m not Catholic, but I have found my own type of spirituality thanks to Corita. And I don’t think I’m the only person that aligns with that type of thinking—finding gratitude in the moment and meditating on your own output into the world.

It’s so hard to take in the world right now. Every day, you’re bombarded, especially on social media, with everything that just breaks your heart and you don’t know where to start to help. And thinking of Corita’s “finder,” a one-inch-by-one-inch square, as social practice, it’s so much easier to say, “Okay, I’m gonna take this part in so I can get an idea of the bigger whole.” We can’t solve all problems, but we can solve this one here in this little moment. And if we start there, then we can keep expanding. There’s a reason why, when we were trying to save her former Immaculate Heart studio in Los Feliz from demolition, and people called in with their support, they weren’t talking about just the product that happened in that space, the artwork that was created. It was about what occurred there in a very spiritual way. And isn’t community in itself an act of spirituality and faith?

I think so. It’s where I find it. One of my transitional life moments was in 2016 when I came across Harrell Fletcher’s work and saw for the first time the work I do in community as sustained social practice. I would suggest that Corita Kent’s 10 rules—in the way that students were fully engaged in contributing and even the intention of evolution over time—was also a social practice endeavor.

Nellie: The rules are so beloved. They’re a structure that everybody—even some politicians have them hanging in their office—can point back to. One rule will speak to you more than another on a different day or in a different context. My understanding of the rules creation is that it was asked of [the students] as a group, What makes a good student? What makes a good educator? Everyone contributes in that scenario. From there, Corita curated these rules. There are actually a few different versions. Barbara Loste, a student of Corita’s, did the first layout of the ten rules. Then David Mekelburg, a celebrated calligrapher, did the layout that’s the most recognizable today. So while it’s really easy to say, “These are Corita Kent’s 10 rules,” it’s like, yes and no. She curated the social practice and it got documented, but by no means would we want to interfere with the dissemination of these rules by claiming ownership. We really approach it as a very educational tool.

L: I foist these rules on anyone I come in contact with. I coached women’s rugby; I gave them these rules. I talked to little kids; I gave them these rules. Especially the line at the end that says, “There should be new rules next week.” Because by having strict discipline and devotion, there’s a freedom at the end of it, that there are new rules. All of that devotion is going to give you something really exciting back, something really fulfilling back, ’cause even if you don’t sell your art, there’s something about making something and then having people react to it, and understand where it’s coming from.

Lukaza: I love the idea of [the rules] being this map for life for everyone. Those are the rules that we should live by. And also they are beyond rules, they’re how we hold each other…

L: …devoid of religion or politics. It’s just human.

L., what do you mean when you say there’s freedom in these rules?

L: This set of rules, they set me free because each one of them is a gift. It’s a pathway, a light in the darkness. When I follow these rules there’s illumination. That’s my freedom, because if I’m not thinking this way, if I’m not considering everything an experiment, if I’m not really thinking about being a good student, then nothing’s going to really benefit. It’s all going to be superficial. And there’s no freedom in that. You’re still trapped by mundanity [laughs]. Once these were shown to me I felt like anything was possible. and what’s more free than that?

Lukaza: It’s so beautiful to think about the power of this list of words and all the ways that it’s seeped into our bones. I think of each rule as its own tool to be used to support us or guide us at different points. Whenever I’m in a classroom setting, before I hand out a syllabus I hand out these rules—but also in other spaces, like organizing spaces. Like, let this be our groundwork and then let’s see where things go. It’s such accessible language in a way that art making isn’t always. Corita’s language is people’s language. “Consider everything an experiment.” Okay, that means a million things. And that’s the work, to know that the million things that means is the experiment of life.

Nellie: I think each rule could probably be broken down to its own mantra of sorts. We’ve seen them applied in so many different ways to people’s practice. When we think about Corita’s pedagogy overall, and the Learning by Heart book she co-authored with Jan Steward, there is this idea that there is always room for flexibility and for your own hand. She didn’t want people to copy her work. She wanted people to make their own work. I’ve never seen a Learning by Heart book that’s not well worn and well loved. I think that’s very similar to the 10 rules, people come back to them. I was very fortunate to have a copy of Learning by Heart with me at the start of the pandemic. And I jokingly said, “It feels like she wrote this in quarantine.” Look at the shadow. Look at the shadow move. It’s like, “Were you in quarantine, too?” [laughs] But [the book’s practices] were so applicable to centering. She’s a printmaker, it’s a very democratic medium. So those lessons, they’re very accessible, you don’t need all these tools to practice. It’s about the practice itself and the process of making, which gets to her quote: “Doing and making are acts of hope.” That’s the goodness. You don’t need expensive materials to get creating. You just need a pencil and to look at the shadows in your room. [laughs]

Nellie, can you speak to the difference between hope and optimism in terms of how they rest in Corita Kent’s work or the way you look at her art?

Nellie: I don’t know if anyone can speak for Corita on what hope meant to her. But there’s a work called “a passion for the possible” from her Heroes and Sheroes series that I reference often because I think the text is so beautiful. At the core of it, it’s hope, not optimism. These are two different things. Hope is hard work. You have to show up every single day to make hope a reality. I think, more specifically where we can cite Corita is on the notion of love and what love really means. She had been commissioned by the USPS to make the love stamp—which eventually sold over 700 million copies. USPS chooses to have the launch at the Love Boat. And Corita is like, “No” [laughs]. She didn’t attend because that was not the love that she meant. She had envisioned it being unveiled somewhere like the United Nations. In response, one of the last pieces she made says, “Love is hard work.” I think it’s a good message to sit with. And for her, it was always about humanitarian love.