- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker September 11, 2012

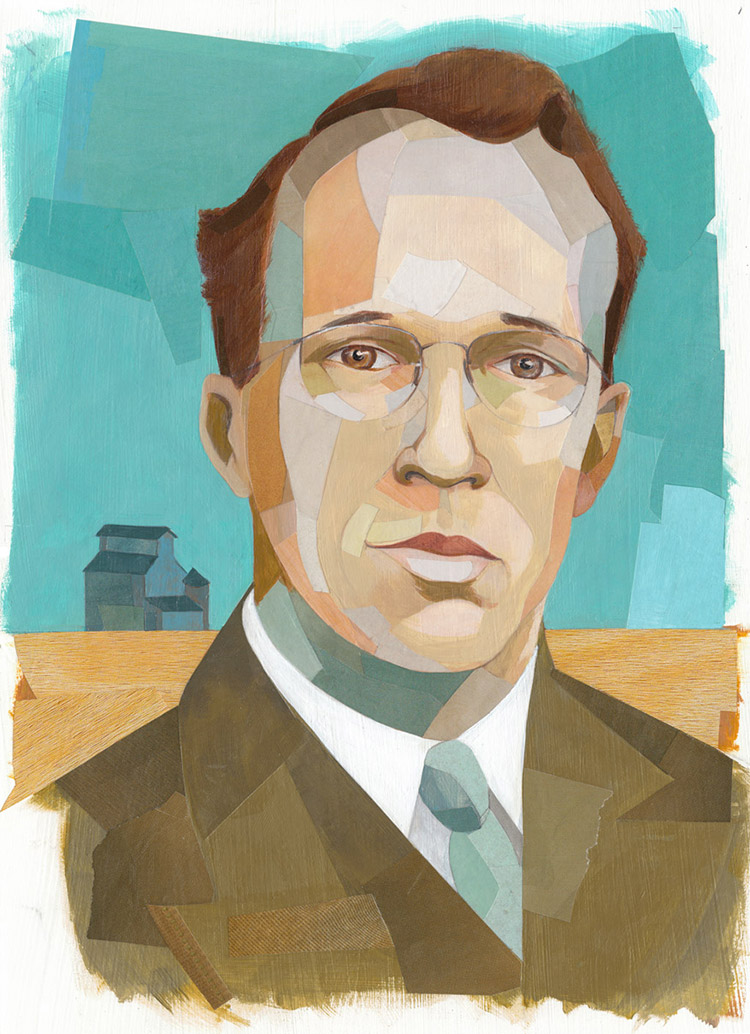

- Photo by Todd Fraser

Darren Booth

- illustrator

- typographer

Darren Booth is a Canadian illustrator and letterer. His client list boasts names such as Coca-Cola, AOL, Target, Penguin Books, McDonald’s, and the New York Times. He’s also created work for high-profile clients Steve Martin and Willie Nelson. When he’s not busy being a perfectionist, you can find him on Twitter sharing cat GIFs or making astute and funny observations.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming an illustrator and letterer.

I don’t think my path is that different from other illustrators—I went to art school and then started working after graduation. I recognized very early on in my childhood that I’d be doing something with art, even though I had no clue what that would be. When I started high school, all my art teachers told me I should go to Sheridan College near Toronto, which is known for its animation program. I thought I was supposed to be an animator because my teachers were guiding me in that direction. Also, some of the people who were ahead of me in high school had went on to Sheridan for animation and when they came back to present to our class and show us what they were working on, it was always really interesting. Once I actually went off to art school, I got six weeks in and I realized, “I don’t think animation is for me.” I headed toward the illustration side of things and right then and there, it was love at first sight.

When I went back home for Christmas after my first semester at college, I looked through some of the journals I had kept in high school. The odd thing is that I had cut out and collected all this work from illustrators—Christian Northeast, Jason Holley, Gary Taxali, Katherine Streeter, Brian Cronin—but at the time, I didn’t realize they were illustrators. Once I learned more about illustration, it was neat to discover that I was drawn to it before I even knew what it was.

Did you earn a bachelor’s in illustration?

I graduated from Sheridan in 2001 and at the time, the illustration program was only a three year program. I came out with a diploma. Now, it’s a four year program where you can earn your degree, but when I went, there was a general first year and then you went into a specific program.

What did you do after graduation?

I started illustrating full-time at first, which I knew was going to be the goal. In my illustration program, I was taught about business, how to work for myself, and the likelihood that I would need a part-time job for at least the first few years. That’s pretty much the path I ended up taking, even though I didn’t get a part-time job right away because I didn’t need a lot to live on.

I graduated in April 2001 and a lot of people didn’t have websites to promote themselves back then. My roommates and I would put our portfolios together and go out and pound the pavement. We had printed portfolios and we’d make the rounds to drop them off and then later, we’d pick them up and do some more rounds. That’s how we got our work in front of art directors.

I worked freelance gigs and saved up my money all summer to put together my first promo, which went out on September 10, 2001. The next morning I woke and saw the planes crashing into the World Trade Center towers and I didn’t know what was going on. I thought, “Oh no! My promo!” Once I figured out the magnitude of what was happening, I realized it didn’t matter what was going on with my promo. Everyone went dry after that and it was a struggle to make ends meet.

Ryan: So you’ve basically been working for yourself since you graduated.

Kind of. It was about two years after I graduated that I realized I needed to make more money. I had moved from Oakville, which is where Sheridan is, to Toronto, which is more expensive. I started working as a wiretapper for one of the largest police forces in Canada; I did that for two years. I spent six or seven days a week intercepting criminal communications and the rest of my time was spent illustrating. I wasn’t super busy as an illustrator at the time, so I was able to swing the full-time day job. When illustration work came, it was okay because it was an extra $500 or $1,000 bucks here and there. But when illustration got really busy, it started to interfere with the wiretapping job—that was such a weird job and a very weird time in my life.

Tina: Did you feel like a spy?

Yeah, pretty much. I couldn’t tell anyone about what I was listening to and a lot of people didn’t know that I was even doing the job. I can talk about it now because it was so long ago, but at the time, it was like I was leading a double life.

Tina: I need to know more about this. What did you actually do all day?

It wasn’t like the movies where you go in and put a bug under a guy’s chair and all of a sudden, you’re hooked up. It’s a little more complex than that. The police have to go through the right channels and motions to make sure everything is legal. But once that part was done, we were pretty much locked in a room with no windows. We had a code to get in the room and nobody else was allowed in, except for the cops who were working on the project or my sergeant. The cleaning staff weren’t even allowed in; we had to clean the room ourselves because the nature of the information we were collecting was just too sensitive and could have easily fallen into the wrong hands. We listened to criminal organizations, murderers, drug dealers, bookies, the girlfriends or wives of the criminals themselves, or their family members. Sometimes we’d listen to bugs placed in cars or homes so we could get information that wouldn’t be disclosed over the phone—most of them had been caught before, so they were smart enough not to talk about things over the phone. We spent a lot of time building cases and waiting for someone to flip on somebody or say something incriminating.

I think you have to be cut from a certain cloth to be involved with that line of work. Now, I look back and realize I was really grumpy and suspicious of everything for those two years that I was listening to the underbelly of society. It definitely took a toll on me.

“…one of [my jobs] had to give and it wasn’t going to be illustration. I had…devoted my entire life to art; I wasn’t going to stop and do this other thing just to make ends meet.”

Ryan: Do you think that job affected your creative work at the time?

I never thought about it, but I don’t think it did. It was like flipping a switch. I would work my ten or twelve hours and the second I was done, I’d flip the illustration switch on. It did affect the amount of personal work I could do because my personal time was so limited.

Tina: We’re going to call your interview, “The Secret Life of Darren Booth”.

Or, “Booth Sleuth”.

(all laughing)

Did you get to the point where you had enough freelance work and could quit your day job?

Yeah, near the end of my time there, the job started to get in the way of my career. I was working 50 or 60 hours a week, but was also getting more illustration work—one of them had to give and it wasn’t going to be illustration. I had went to school and devoted my entire life to art; I wasn’t going to stop and do this other thing just to make ends meet. I said goodbye to the wiretapping job and started illustrating full-time and that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.

Where did you grow up?

Sault Ste. Marie, Canada.

Was creativity a part of your childhood?

For sure. When I was small, I’d go to Saturday classes offered at the art galleries. My parents never discouraged me from creating; I think they were happy that I was keeping myself occupied with drawing. If I wasn’t drawing, I was doing something else with my hands—playing with Legos, taking apart my bike.

Did you have an “aha” moment when you knew that illustration was what you wanted to focus on?

Yeah. It was the moment I talked about earlier when I was six weeks into my first semester at college. Once I started seeing projects from the animation and illustration programs displayed in the halls at school, I knew what was for me and what wasn’t. From six weeks on, I completely shifted away from animation and toward illustration.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

In my final year of high school, I had to do a small internship, which I did at a local screen-printing shop. There was a guy there named Jay Muncaster, who was the in-house artist and he had actually went to Sheridan about ten years prior to when I attended. He studied animation and came back to Sault Ste. Marie, started a family, and opened a screen-printing shop. He was really enthusiastic about the programs he had learned and he taught me Photoshop—it was Photoshop LE of all things. That was the first time I jumped on a Mac. He showed me the ropes and got me ready for school. Because of him, I had a better sense of what to expect when I went away to college. Working there was also great because I learned how to present ideas and interact with clients, which is still helpful to this day.

In college, I had a lot of great teachers—Joe Morse, Paul Dallas, Blair Drawson, Gary Taxali, Lorraine Tuson—who were also all working illustrators.

In my final year of college, I interned with Gary Taxali and he was great because he took me under his wing, almost in a similar fashion as Jay did. He is brilliant and I owe a lot to him. One specific thing I learned from him was the kind of business person I wanted to be. He’s very outgoing and active. He can promote himself ten times a day and because he’s so genuine about it, people don’t get annoyed. As much as I learned from him about how to work with clients and what it’s like in the real world as a freelancer, I also learned that I couldn’t promote with that same approach. Our personalities are very different and if I promoted myself ten times a day, I’d have two followers on Twitter and they’d be spambots. Gary’s business and art reflects his outgoing personality, but I’ve learned to cater my business and promotions to my personality as I’m much more reserved. I’d rather just throw my stuff out there and say, “This is my shit. I hope you like it. Here’s my contact information.”

Was there a point in your life when you decided you had to take a big risk to move forward?

I don’t know if I’d call it a risk—it was more of a kick in the butt. It was when illustration work was starting to become a full-time gig and I was still working the day job. I gave up the income and security of the full-time job to submerse myself completely in the freelance side of things.

Tina: Were you scared that maybe it wouldn’t work out?

Yeah, and then I’d have to crawl back with my tail between my legs and ask for my job back. But it’s good to have that fire under your butt because it makes you work harder—you know that every image you make is an advertisement for yourself.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do and who has encouraged you the most along your creative path?

Yeah, everybody has been been pretty supportive. Most of my family doesn’t quite understand what I do, which I don’t think is news for a lot of creatives. My family likely thinks, “He sits around in his underwear drawing pictures all day and he’s probably doing okay because he’s not sleeping on our couch or asking us for money.” But I don’t really know what my relatives’ jobs entail either, so I think it’s a mutual thing.

My wife has been super supportive. We started dating when I was in college and she’s seen how much time and effort it’s taken me to hone my craft and skills. She’s witnessed the ups and downs of freelancing and seen how long it’s taken me to build the business to the point where I don’t have to worry about paying the bills.

Ryan: We’re always interested in this because we both do creative stuff. Is your wife also in a creative field?

No—complete opposite. Well, maybe not completely, but almost. She went to school for health sciences and is wicked smart.

I’m pretty much the only artistic person in my family. I don’t come from a typically “artsy” family, but I do come from a family with a lot of meticulously skilled tradespeople, like carpenters, woodworkers, and bricklayers. Also, my grandma is crafty and being exposed to those types of environments gave me a chance to work with my hands from an early age.

Ryan: That’s interesting. I like asking that question because every couple is so different in regards to what works for them.

It’s neat because I learn a lot from my wife and how she runs her business. She also works out of the house, but we know we can’t work on the same level, so I got relegated to the basement. Well, I chose the basement and built a studio down here and she uses one of the spare bedrooms on the second floor. She’s on the phone a lot and if I want to play guitar or listen to music, that interferes with her work.

As a freelancer, it’s easy to take things personally when an art director or designer asks you to change something, but it’s just business—they need something particular. It took me a long time to figure that out and realize it wasn’t a knife to the heart every time I was asked to change something. My wife has always been good at talking me down when I get worked up. She has a good business sense and can suggest different approaches. I’ve learned a lot from her when it comes to business, whether she knows it or not—well, I guess she’ll know it now.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Can I be 100% honest?

Of course.

No. Not at all. I probably should and I feel a little bit bad saying that, but not really—not in the industry. In my personal life and as a father, I feel completely responsible to be a good husband and dad. In illustration, I don’t see myself as that person; I just like making images and putting them out there. That’s my position in the industry. I realize I won’t ever be a mover and shaker. People have likely seen my work and not realized it was mine. I still get emails now, two years after that book cover I did for Steve Martin, where people say they’ve been following me on Twitter for a long time, but didn’t know that was my work. I’m hiding in plain sight, I guess.

Are you satisfied creatively?

That’s a loaded question. I guess I’m satisfied with my perpetual creative dissatisfaction. Does that make sense? What I’m trying to say is that I know I’ll never be satisfied and I’m cool with that. It’s okay if I make a piece now and I’m happy with it and then two years from now, I hate it. I almost expect that to happen.

Ryan: Best answer ever. That describes the name of our site.

Well, it’s true. It’s a great question.

“…I’m satisfied with my perpetual creative dissatisfaction…I know I’ll never be satisfied and I’m cool with that.”

Is there anything you’d like to be doing in the future that you’re not doing now?

There are some projects I’d like to cross off my career bucket list, but I don’t have anything planned. Every once in a while, I like to reassess my portfolio and figure out where I have holes in it and how to fill those holes. That could mean I need to add a particular piece to my portfolio or go after a certain client. For example, a few years ago I hadn’t done any book covers, so I put a few personal projects of book covers in my portfolio and work started coming in. In the future, I wouldn’t mind doing film titles or titles for the intro of an HBO or AMC show. Larger scale work would also be great—like a Times Square billboard.

Ryan: We don’t usually talk process, but I’m curious—do you do most of your work digitally? It feels very analog.

It’s about 99% analog. The only digital part is when I scan work. I might take a couple sketches, knowing that I’m going to piece them together in Photoshop and play with the scale or composition rather than redrawing the elements. At one time, I would photocopy it larger or smaller, cut it out, and place it that way, so eventually my sketches would be four or five layers and covered with tape. For the final pieces, I do the ol’ pencil on the back of the paper trick, copy it to a new piece of treated print-making paper, and start painting.

When I started mixed collage with my paintings, it was just out of laziness because I didn’t feel like whipping out the paints again and repainting an area. Instead, I just cut out a piece of paper, stuck it on, and it was done. I was catering to my own laziness and eventually, it became a thing.

In some ways, I feel like a dinosaur because I am working traditionally. I need to feel the work and be able to respond to what’s going on on the page; that’s what keeps me interested in the piece. I’ve done some work in Photoshop, but I feel like I’m just sitting there, staring at a computer and it doesn’t seem natural to create that way. But if I’m designing or tweaking my website, I love being on the computer.

I also like having a tangible piece when I’m done. There’s something magical about seeing a painting from Picasso in a book for twenty years and then seeing it in person at a gallery and realizing, “Holy crap! It’s huge.” Or, you think it’s huge and the painting is tiny. I don’t think I would be satisfied if I produced a piece 100% digitally and had nothing to show for it other than a PSD file.

If you could give one piece of advice to another illustrator starting out, what would you say?

Maybe it sounds trite, but I’d say to make the kind of work you want to make. I think when you’re in school, you start out making the work you want to make, but then you get out and the industry starts to mold you in a certain way. If you keep making the work you want to, eventually work will come in.

In regards to the hand-lettering work I do, I probably made 30 or 40 pieces before I even got an actual commission. I had it in my portfolio for a long time and art directors would say, “That’s great, but I don’t really know how to use it.” Nobody used it back then, but now the market is over-saturated with it. I think I can hear the clock ticking on it, but I’m going to ride the wave as long as possible.

I would tell young people not to worry so much about having an original style. I would say to just focus on doing good work and the rest will come. As long as the work is good, I think people will respond to it. Style is a result of good intentions.

How does where you live impact your creativity?

I’m a homebody for the most part. I’ve lived in Toronto and Montreal, which are pretty busy and creative cities, but they never really affected what I was doing. As long as my home environment and my studio are a comfortable place to operate—that probably has more of an impact on me than the actual city I live in.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Yes and no. Definitely not in the current city I live in because we don’t even have a decent art store. I’m in St. Catharines which is about 20 minutes from Niagara Falls and I’ve resorted to buying art supplies online or driving over an hour to go to the art store. Community-wise, there’s not a lot going on here, so I forget that it’s important. If there’s an industry event going on in Toronto, I’m reminded that it is important to keep in touch. With the Internet, it’s a lot easier to shoot people an email and chat back and forth—that’s become my creative community.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Well, I just wake up, do some art, and go to bed. (laughing) I’m a night owl, so I do my best work from 10pm to 2am. I get more work done in those four hours than I will in say, eight hours before that. Normally I wake up, hang out with my wife and the baby for a bit, and then go to my studio and figure out what I have to do that day. Unless there’s something that really needs to get done, it takes me a few hours to get up to speed. I’ll work for a little bit, but I don’t have a set schedule. I might take a break to go get my son from daycare or do some chores around the house. It’s a lot easier to get work done at night when the phone isn’t ringing and there aren’t emails coming in. That’s about it.

What are you currently listening to?

Well, it probably sounds like I’m kissing butt just because I did her album artwork, but I’m listening to Kathleen Edwards’ latest, Voyageur. I’ve been getting into Dawes lately and I’ve always got a mix of Ryan Adams, Bruce Springsteen, and Bob Dylan—all that dad rock.

Any favorite movies or TV shows?

Breaking Bad is my favorite TV show. Draplin said this and so did Jeff Rogers, but Shawshank Redemption is hands down my favorite movie—the three of us should probably have a Shawshank party and cuddle on the couch together.

Do you have any favorite books?

Uh, the dictionary? (laughing) I’ve got nothing; the Internet has ruined my attention span for reading. I do love The Catcher in the Rye.

Favorite food?

Any kind of chicken.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Last year, I probably would have answered that question by saying I want to be a famous artist and blah, blah, blah. After having a child, my perspective has changed. I think that in the grand scheme of things, art and swashes and ligatures are probably only going to make up 5% of the legacy I want to leave. Legacies don’t build themselves, so hopefully being a good dad, a good husband, and being regarded as talented, even if I’m not famous, will add up and create a larger picture that I get to see at some point.