- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker May 7, 2013

- Photo by DDB

FAILE

- artist

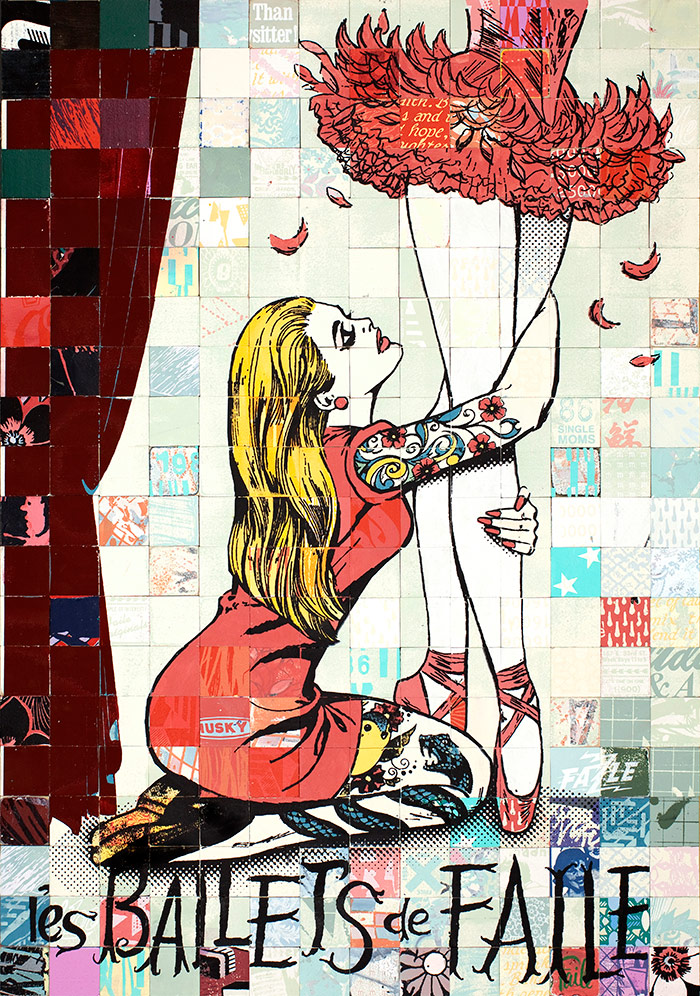

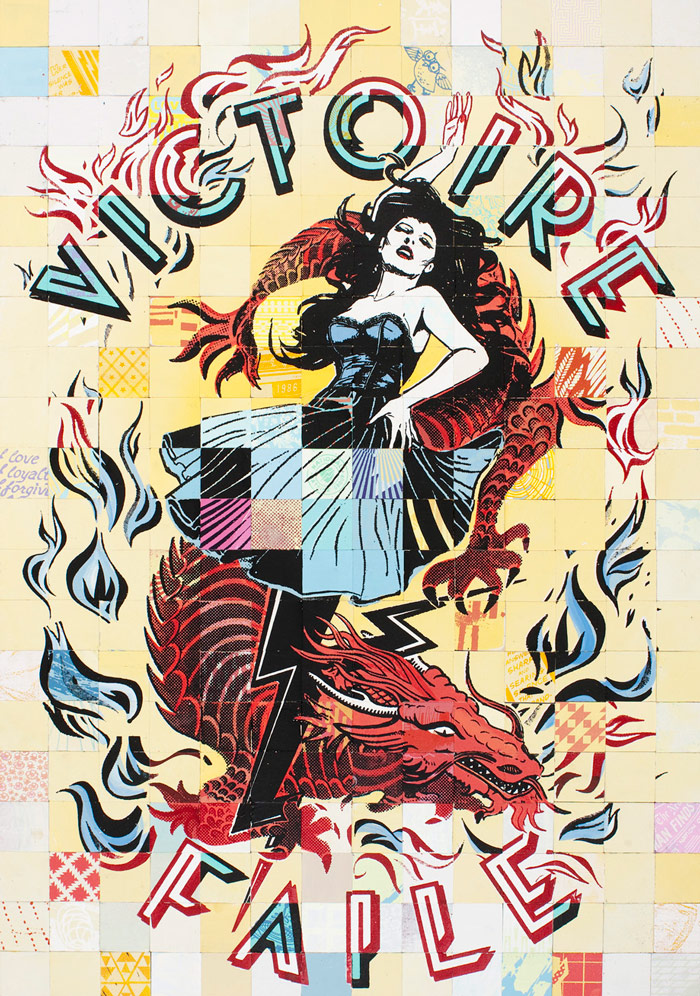

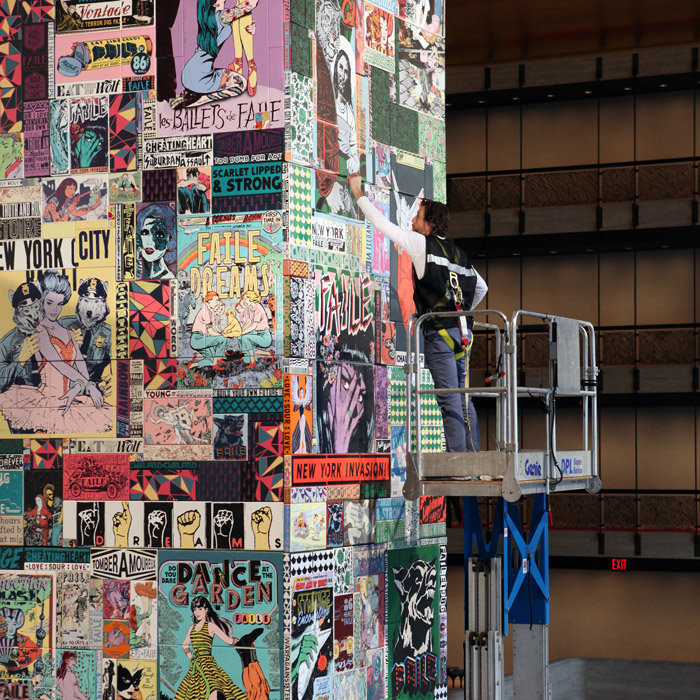

FAILE is a Brooklyn-based artistic collaboration between Patrick McNeil and Patrick Miller. Since its inception in 1999, FAILE has become recognized as one of the leading artists in the contemporary Urban Art movement. Their work explores duality through a fragmented style of appropriation and collage. The duo has been exhibited in various galleries, museums, and non-traditional venues throughout the world.

Interview

Describe your path to becoming artists.

McNeil: We met on the first day of high school when we were 14. I had just moved from Canada to Scottsdale, Arizona, and Pat had already been living there.

Miller: I had moved to Scottsdale when I was seven.

McNeil: On the first day of school, when attendance was called in each class, the teacher said, “Patrick…” and I raised my hand and then the teacher said, “Miller.” My last name is McNeil, not Miller, so I lowered my hand. After a few times of this, I realized I wasn’t on the roster yet because I was new. The fourth time this happened, I was sitting next to Patrick Miller in gym class and when he raised his hand, I said, “Hey, I’m Patrick McNeil. I’ve been raising my hand all day thinking they were going to call my name, but they kept calling yours.” And that’s how we met.

(all laughing)

We went to Chaparral High School together for four years and during that time, we had a common passion for art and shared art classes taught by a great teacher named Marcy Warner, who we learned a lot from.

After high school, we both went to Northern Arizona University to study art for a year. Then I went to England for a year before I came back to Arizona for one more year. Miller moved to Minneapolis to study graphic design at Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) and then I moved to New York City to study graphic design.

Miller: Along the way, we traded sketchbooks and liked the idea of making work together, similar to being in a band. We also influenced each other a lot. For example, when Patrick came back from England, he introduced me to stenciling, which was a new way for me to work. As I saw him being excited about things, I would try them, too. Our styles lent to each other very well; we both liked color and typography before we ever knew what graphic design was. Our interests continued to evolve and we both went away to different art schools to study fine art, but ended up studying graphic design because that seemed like the better option for getting jobs after school—we figured we could always paint on the side. Fortunately, we both went to schools that recognized our interest in fine art within the design program and let us take a lot of fine art and screenprinting classes. We started doing work with large-scale monoprints and silkscreens, and it was really Patrick being out in NY that inspired us to take that work to the street.

McNeil: Yeah. My first job was at Pearl Paint on Canal Street and that area was covered with street art, layers of graffiti, and textures; it was awesome absorbing that kind of surface for the first time. As I walked to and from work, I photographed and started taking note of what was going on graphically with art on the street at the time. I wanted to get involved. After a year of documenting, we started putting up little stencils.

Then we talked about starting what we initially called Alife, which became FAILE. The first project we decided to do was a series of female nudes based on photographs that I took. We thought they would be fitting with “Alife” because they were representational of a classic figure and were in contrast to what was going on at the time; street art was very masculine—a lot of propaganda, guys fighting, and other male-loaded imagery. I went to Minneapolis, where Pat was in school at MCAD, and we printed all these nudes. Our first action was putting up 100 of those prints all over New York City and documenting the process of how they broke down.

Miller: That was in 1999. We took what we were doing with the large-scale monoprinting and turned it into posters for the street. We were interested in how the art would translate from the studio to the street and, in the beginning, we were really excited about starting dialogue. We’d put something out on the street and it would get covered over, ripped, written on—it felt like a living, breathing piece of art. We didn’t have to ask for permission to do it; all of a sudden, we existed and had a voice.

Did you guys respond to interactions with your work?

McNeil: Yes. There were definitely artists we met through doing that. You’d put your work up next to theirs; they’d put theirs up next to yours; and a dialogue would start between people as they were reworking the same spots.

Miller: We documented that along the way and so much of our work has built up from incorporating images, then remixing and collaging by cutting and pasting. That fueled the fire for us to create new work.

How did your paths evolve from doing that first series to now?

Miller: It was a long path. (laughing) In 1999, we were still in art school. We were fortunate to be motivated and driven to make and produce a lot of work while in school. We were exploring what was just then becoming FAILE. We had the time; we had the creative environment; we had access to free ink and large space to work. Otherwise, it was us printing out of Patrick’s tiny apartment in New York. We took advantage of everything we had available to us, including student loan money, which we used to travel. We also worked with Aiko Nakagawa, aka Lady Aiko, at the time and she and Patrick traveled a lot in the early days.

McNeil: Yeah. It was all about the lifestyle of traveling, seeing places, and putting work up.

Miller: It was so organic back then because there wasn’t the term “street art”; it was just a small group of people who were working on the street in various pockets.

Up until then, the model for becoming a fine artist was attending college, going to grad school, finding a good gallery, getting introductions to curators, and being legitimized through museum shows. That was the arc. But when we started putting work up on the street, the Internet was starting to happen and we could share our work with anyone. All of a sudden, there was potential for our audience to grow exponentially. In the beginning, that’s what it was about—just getting work out there in front of people.

McNeil: From there, our work developed. We did a lot of stenciling and wheatpasting on the street and after a while, we wanted to try different things. Getting bored of process inspires you to continually try new things.

Miller: In the meantime, I moved to New York City in 2004. In 2005, we got a studio together on N. 6th St. between Kent and Wythe in Williamsburg. It was a big stretch for us, but it was exciting because it gave us a huge space to work in, which made a big impact in terms of our work and what we could do with painting. It allowed for our work to really grow. In 2006, Aiko left to go out on her own, and around that time we started to push painting. That’s when we started doing ripped canvases, which were coming directly from working on the street, except we were painting the tears. Our whole process was unfolding in a dramatic way; more and more shows were starting to happen; and the Internet was sharing in a big way—there was momentum building.

“Our work is about narratives, telling stories, and searching for meaning through modern mythology and archetypes—it’s almost like sifting for gold.” / Miller

Did you have day jobs during all of this?

McNeil: We didn’t have day jobs, but we took on freelance projects, which we relied on to pay the bills because FAILE wasn’t making anything substantial at that time.

Miller: But everything we were doing was to get FAILE to the point where we didn’t have to take on freelance projects and we were committed to making that happen.

McNeil: Everything changed when we sold prints online for the first time and they sold out.

Miller: That was in 2006 and it was a huge turning point. We started selling prints online and people were buying them. Soon, we no longer had to take on freelance work to pay our rent. Because of that, we could focus on making more prints and all of our energy went into FAILE.

How long have you been doing FAILE?

Miller: Since we were in school, so we’ve been doing FAILE for 13 years.

Ryan: I noticed that you have people helping out in the studio.

Miller: Yes. We have assistants. I like to think of it as being similar to working with a group of talented musicians. We are the ones who write the music and compose the score, but we work with really talented musicians along the way; they can belt it out and do great things while having an impact on the overall symphony, but we’re still directing them along that path.

For our readers who might not be familiar with your work, what kind of work are you doing right now?

Miller: What you have to know about our work is that it all starts with making images. Our work is about narratives, telling stories, and searching for meaning through modern mythology and archetypes—it’s almost like sifting for gold. Today, there is a constant influx of images and we are being bombarded with information. How do you sift through that, what are you left with, and how do you find meaning in it? That’s what our work is about—taking all those common visual cues, stories, cliches, and archetypes to form a new meaning with our language in order to tell the stories we want to tell. Everything starts there. The images then go into the studio as a whole and are disseminated from there. They might become silkscreens, paintings, or sculptures.

Along the way, we’ve been challenged to rethink what we are doing and what we want to say. At first, street art was about engaging the public, but after time, it exploded and there became this commodification of the art. That led us to try new projects like prayer wheels, the Temple, and Deluxx Fluxx Arcade, which were still about engaging the public, but in a way that catches them off guard so that we can really have an impact with our message. That approach has become a big part of our practice.

Our work changes, too. For example, the Wolf Within Sculpture started as a black and white image for a show we did called Lost in Glimmering Shadows. It was late 2007 and the economy was insane; everything felt filled with materialism and greed, and we reimagined what it would be like if Native Americans came back and overtook the city. The resulting image, called “Eat with the Wolf,” was about this man having an epiphany; he is wearing a wolf pelt, tearing off his suit, and kind of being in rapture. Then we were asked to do a project in Mongolia last year and, as we do with every project, we were researching the area. We discovered that it was a largely nomadic country with a rich history of living in the desert and being part of the land. But now, Russia and China are drilling the hell out of it and going after mineral rights. We started to think about all the people who would never benefit from what that land has to offer. Suddenly, the “Eat with the Wolf” image of a businessman tearing off his suit to reconnect with nature became a perfect fit and now, it’s a permanent sculpture in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. It’s crazy to go from doing street art on such a temporary level to having a public sculpture somewhere on a permanent basis.

“Sometimes it’s necessary to hit the reset button and trust that something positive will come out of it, even if it’s scary as hell—hence the name FAILE.” / Miller

Was creativity a part of your childhoods?

McNeil: It’s been a big part of my life ever since I can remember. It allowed me to connect with friends and was a talent I had that I could hold on to and enjoy. My parents always encouraged me by buying me art supplies and taking me to museums. I was very nurtured.

Miller: I had the same experience. My parents were very supportive. My mom was a teacher when I was young, so she exposed me a lot to children’s books, and I got to meet several authors, which was exciting. I think my parents recognized my passion for art early on and supported it. There was never any question that I would go to art school, other than the cost of it—because it is so expensive.

Did either of you have an “aha” moment when you knew that you wanted to be artists?

McNeil: I think seeing street art for the first time was a big moment. When we were actually doing street art, it was when I saw our work pop up in a magazine. That was exciting.

Miller: Yeah. In the early years, I was just excited about getting the work out there and possibly having something be seen. We were inspired; our work was speaking to the city; and then we became a part of the tapestry again. That circle is interesting to see.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Miller: I feel like we’ve had a lot of people who have been really great in terms of pushing us, helping us, and opening doors. Marcy Warner from Chaparral High School was one. Bill Thorburn, who was from the advertising and design world, was supportive and taught me a lot about process when I interned with him. There are almost too many people to name.

McNeil: I went to the Fashion Institute of Technology here in New York and had a teacher named Larry Toth. He was one of the last teachers to accept me as a student in his class because I had taken each class so many times that no one wanted to let me in. He also owned a poster restoration company and gave me my first internship following school. His company restored thousands of old movie posters and that was great to be around. Also, I met a close friend in college in England named Mike O’Neal, who was a huge support and inspiration early on and still is to this day.

Have you had a point where you’ve had to take a big risk to move forward?

Both: (laughing) Yes.

McNeil: There are different types of risks—the most important being the creative ones. I think you get to a point when you’re doing something where you just need to change and do something different.

Miller: We’ve taken a risk in our work a few times in our career, and it usually throws people off. Whenever we’ve done it, it’s cycled back into the work in a way that’s been really important for us, even if it’s not a popular thing with our fans and collectors. One of the things we talk about a lot is continuing to take risks and letting our audience know that we are going to do that. We need to have the periphery to explore. The last show we did was called Fragments of FAILE and it really looked at stripping away a lot of the way we make images and tell stories. For us, it was about painting and it was a really great experience, even though I think people were surprised. I hope that over time we can build that element of surprise into what we do.

Sometimes it’s necessary to hit the reset button and trust that something positive will come out of it, even if it’s scary as hell—hence the name FAILE. (all laughing) That’s something we really embrace and it relates to taking risks and growing from them. It’s literally the moniker we work under so it’s important that our process reflects that. That’s the other thing—process. Through printmaking and working on the street, we’ve learned to embrace those serendipitous moments and let the environment or mistakes in the studio or our assistants have a hand in the work.

McNeil: You have to embrace collaboration because, even in the streets, your work is subject to collaboration.

Miller: It’s good because collaborating keeps you in check. You can’t go too far down a path without having somebody to bounce the work off of. It makes you answer questions about your work and that makes the work stronger in the end.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Miller: Hugely. I mean, that’s another evolution—we’re both married now and we each have two kids. That’s a big change, not only in the way it affects you creatively, but also in the sense of the amount of time you can spend on work. We have much more responsibility now and, in a sense, FAILE is becoming a very big family. That does affect us. Having kids has made us think about what we say with our work and what we will leave behind. I think about our work as little breadcrumbs we’re leaving about ourselves and how we feel in each moment. Not only are we leaving those behind for everyone, but we’re now leaving those behind for people we’re really close to.

McNeil [pointing to Miller]: I’m with him.

Is it difficult to find a balance between work life and family?

McNeil: We work too much lately.

Miller: We miss out on a lot. The fortunate thing is that we do what we love; we’re putting something into the world that we believe in and I think that makes us better people. At least that’s how I rationalize it to myself when I only see my kids for an hour in the morning when I get them ready for school because, by the time I get home at midnight, they are already in bed.

McNeil: The other good thing is that we’re aware of how much we work and we try to get a lot of family time in on the weekends.

Miller: Yes. Weekends are sacred.

McNeil: I hope it’s not always this crazy.

Miller: We have each other, too. Since we both have families, we understand if one of us needs to go be with our family for some reason. We do rely heavily on our assistants to help us out and, thankfully, we have a lot of flexibility in our jobs.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Miller: Personally, yes, I do.

McNeil: That’s always been part of the practice as well. We contribute a lot of work to charity auctions and things like that. Anytime our work can support things like that, it’s great.

Miller: I also feel like the message we put out there is making an impact. People email us or talk to us at shows about the pieces they like and why they connect with a specific one. When we do huge murals in cities, people see it and are affected by it. More recently, we did subway posters for the New York City Ballet and got these really genuine, sweet emails from parents about how much their kids like and identified with the art. That was really amazing.

Ryan: Speaking of murals, I really like the one you guys did on Houston and Bowery.

Miller: Thanks. Working out there was great. So many people stopped to say they were fans or ask who the hell we were.

Ryan: It’s interesting to see that kind of stuff happen in the city. People naturally love art and seeing the process of how you guys do what you do.

Miller:That’s where the Internet and social media have become such a good thing for us because it removes barriers and allows people to contact us directly or get a sense of who we are and that can be great. Those interactions couldn’t have happened 15 years ago.

“Follow your passion. Don’t chase jobs because of money. You’re going to be doing what you’re doing for the rest of your life and you better love and enjoy it every day.” / McNeil

Are you satisfied creatively?

Miller: I’m very fulfilled, but very hungry.

McNeil: There are times where I feel like a bit of a cog in a wheel and want to try something different, but I feel pretty good lately.

Are there things that you are interested in doing or exploring 5 to 10 years down the road?

Miller: Yeah. We’re pretty good about identifying things we want to do. Doing the temple in Portugal was an incredibly fortunate experience and showed us that we can tackle big things. So much of artwork is production, especially with sculpture. You can make an image in a few days, but spend the next five months turning it into a big sculpture. I think you have to parse out where you can still be creative while also understanding production and running a business. That’s the side of art that a lot of people don’t get. With any kind of success comes having to run a business. You have to try to find the meaning through the everyday bullshit that we all have to do.

What advice would you guys give to a young artist starting out?

McNeil: Follow your passion. Don’t chase jobs because of money. You’re going to be doing what you’re doing for the rest of your life and you better love and enjoy it every day. Do what you love and everything else will work out—and hopefully you can find something you truly love.

Miller: It’s a blessing and a curse to find something you really love. I would say take the leap. Just do it. A lot of people think and think and talk, but don’t do anything. You have to take the leap and once you do, things will inevitably start to happen and you will gain momentum.

You guys are in Brooklyn. How does living there impact your creativity?

Miller: Brooklyn is our muse. It’s exciting to be part of what Brooklyn is today. The music we listen to, the food we eat, the things we read—they are all influenced by Brooklyn and seem to ripple out and have a bigger, more global impact. Walking along the streets every day and paying attention to our surroundings—

McNeil: The signage, surfaces, textures, and breaking down of things.

Miller: We take all of that in and put it out in new ways. It’s an important part of finding meaning in the world by bringing things in, making them your own, and putting them back out in a way that others can take from them.

Do you guys have a creative community of people that you’re a part of outside of your collaboration together?

Miller: That’s where the street art thing comes in. We’ve fought that label, but there’s also the realization that so many artists never get to be part of a movement, which I think this is becoming. We’ve gotten to know so many people through what we do and it’s great to be a part of that community. We’ve been very blessed in that sense.

What does a typical day look like?

McNeil: Wake up early with my kids, try to contribute by unloading the dishwasher or making some lunches or taking the trash out. Then I commute an hour into the studio. Pat drives in and we both get here by 9:30am, have coffee to get our brains going, and talk about things for the day. Days either flow creatively and we get down to work or we tend to get bombarded with distractions.

Miller: We keep regular hours because there’s no way we could run a studio without doing Monday through Friday 9:30am to 6pm. Logistically, it’s easier to work late because it’s quiet and you can actually focus.

McNeil: And with so many people on the floor in the studio, you’re always juggling between a few things.

Miller: When I think of some of my favorite times in the studio, it’s usually at night when it’s just Pat and me, and we can step back and reflect on the day or week.

Any music you guys are listening to right now?

McNeil: Music is everything in the studio. I’ve been listening to the new releases on Rdio each week—this week it’s been Snoop Dog. (laughing) Well, he’s actually Snoop Lion now. I also like James Blake’s new album.

Miller: I like Sleigh Bells and am excited for the new Daft Punk. I also just found out about a band called Lorde and they have an amazing song called “Royals.” Patrick and I have different musical tastes, but music is a constant thing in both of our lives.

Your favorite movies or TV shows?

McNeil: Lawrence of Arabia and Game of Thrones

Miller: I like the late-night 1980s John Hughes films: National Lampoon’s Vacation; Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

Do you have a favorite book?

McNeil: Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet

Miller: I’m really into Joseph Campbell, who has a lot of great books about mythology. We’re also both collectors of printed ephemera and books, which are a big part of what we do. We spend a lot of time going to vintage bookstores and finding things online.

Your favorite food?

Both: Mexican food.

Miller: There’s a place called Fonda in Park Slope, which is a favorite, although we go to Vamos Al Tequila down the street quite a bit.

McNeil: There’s a place we went to in Tucson, AZ, called El Charro, which is so good.

Miller: We went to Tucson last January to paint a plane for The Boneyard Project. We were there for one week and ate at El Charro six days in a row. It was incredible.

McNeil: Margaritas every day!

What kind of legacy do you guys hope to leave?

McNeil: I just want some high school kid to be looking through the art section of books and pull out a book on us and be inspired.

Miller: For me, it starts with my kids. I hope I can help them find a kernel of truth in different times of their lives—and for any other young kids looking for their path, I hope that there’s something in our work that encourages them to take the risk.

Bonus Questions

If you could go back and meet your 18 year old self, what would you say to him?

Miller: I don’t want to say “Don’t take yourself too seriously,” because I think there’s value in that, but “Know that everything is going to be okay.”

McNeil (jokingly): Also, I’d say, “Watch out for that girl. She’s trouble!”

If you went into the future and met yourself, what would you say to him?

Miller: Is everything going to be okay?

McNeil: If I met myself in the future? I would ask, “Is everything going to be okay?”

Miller: It’s funny because I always look back, but I don’t look forward in that sort of sense because it’s all part of the journey.

McNeil: You were asking about books earlier and the title of one of my favorite books is The Journey is the Destination by Dan Eldon. He was a young kid who took photographs and kept these amazing sketchbooks. He ended up getting killed in Somalia while photographing a riot. The book is about his life and how he lived it to the fullest. That message that the journey is the destination has always resonated with me.

Miller: Going back to your music question, then—

McNeil: Oooh!

Miller: Being a big Radiohead fan, I listened to Alec Baldwin’s interview of Thom Yorke last night. One thing I was reminded of is the importance of being aware. When you’re in those moments where you are stressed out and right in the middle of things, it’s good to step back and realize how meaningful that time is. I think that relates to your past and future selves. If you don’t “stop and look around once in a while” as Ferris Bueller would say, you’re really missing something.

McNeil: Remind yourself in the future to be present.

“I think you have to parse out where you can still be creative while also understanding production and running a business…You have to try to find the meaning through the everyday bullshit that we all have to do.” / Miller