- Interview by Brandi Katherine Herrera December 21, 2017

- Photography by Gemma Warren

Gary Taxali

- artist

- illustrator

- educator

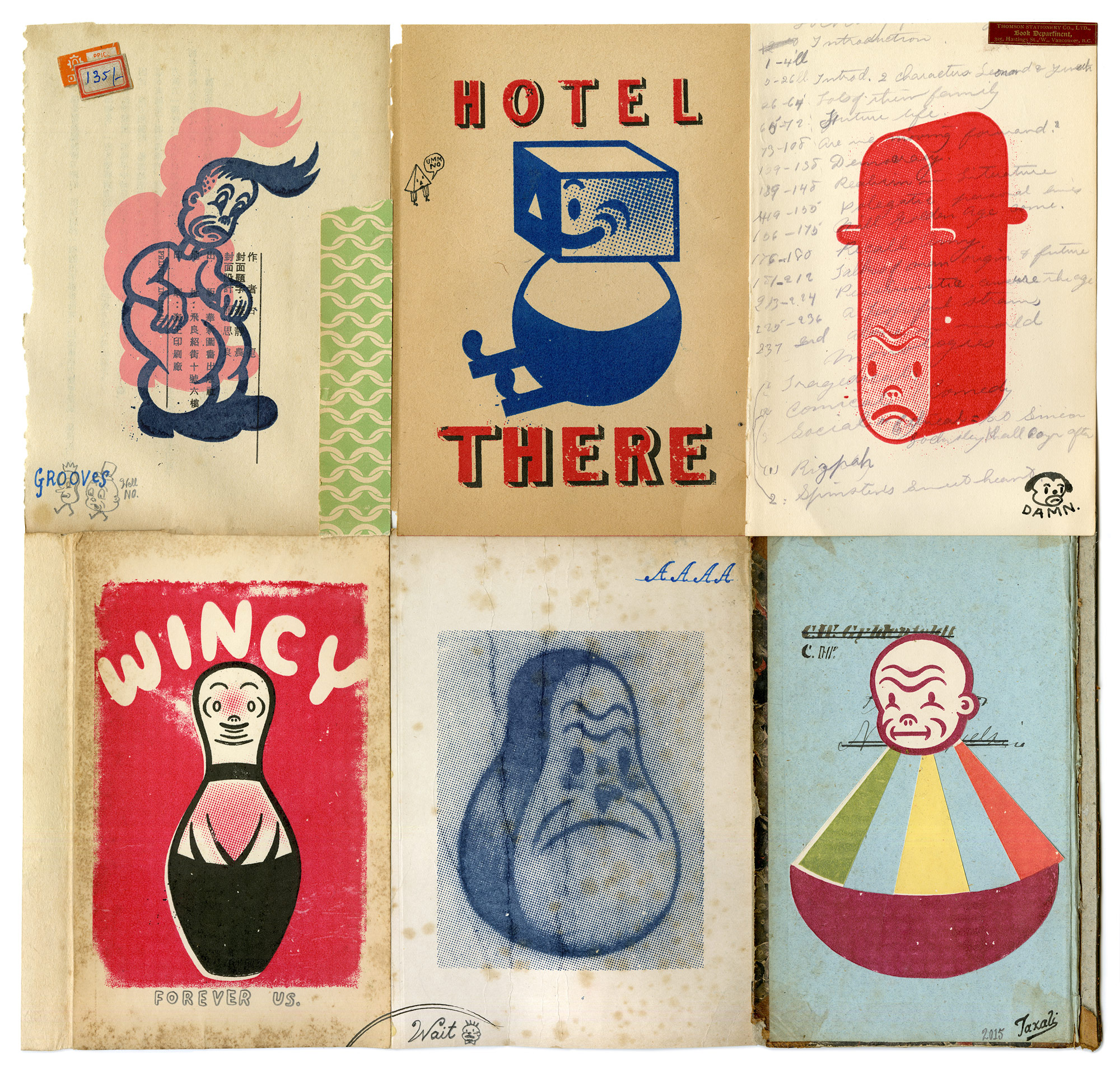

Gary Taxali’s body of work has influenced many artists and illustrators over the years, and the imprint of his distinctive aesthetic has touched everything from children’s books and toys, to album covers, men’s fashion accessories, and even 25¢ coins for the Royal Canadian Mint. Here, he recalls childhood days spent in Toronto’s Little India, and the impact both Bollywood “bad guys” and Hindustani classical have had on his work; why he’s always felt like he was born in the wrong era; and how he’s channelled his lifelong love of the classics into a successful, decades-long career as an artist, illustrator, and educator.

You were born in India and raised in Toronto—did Indian or Canadian art and culture play a role in shaping your early ideas about creativity? I was born in India, but when I was about a year old, my family immigrated to Canada and we settled in Toronto. From an early age, I was really influenced by my father. He didn’t draw or paint for a living, but he knew how, and I would watch him and he would give me lessons. I would ask him to draw things for me, like a cowboy, and he would. And then at a certain point, he started asking me to do those kinds of drawings, and would help me with form and give me tips. Eventually, he enrolled me in community-center art classes, which I absolutely loved. He was terrific. My mom, who was a different kind of influence, was so positive about everything I did. I would draw pictures to make her laugh—and she did.

I think the combination of the positive, uplifting support my mom provided, along with my dad’s more critical kind of support, was a really nice balance. It was kind of daunting, though, when I started school. I would draw pictures, but would get comments from teachers that they were too silly. I was allowed to do that at home, so I was getting these mixed messages. Luckily, I realized at an early age that the support of my family was more important. It gave me vitality, and the courage to keeping going with it.

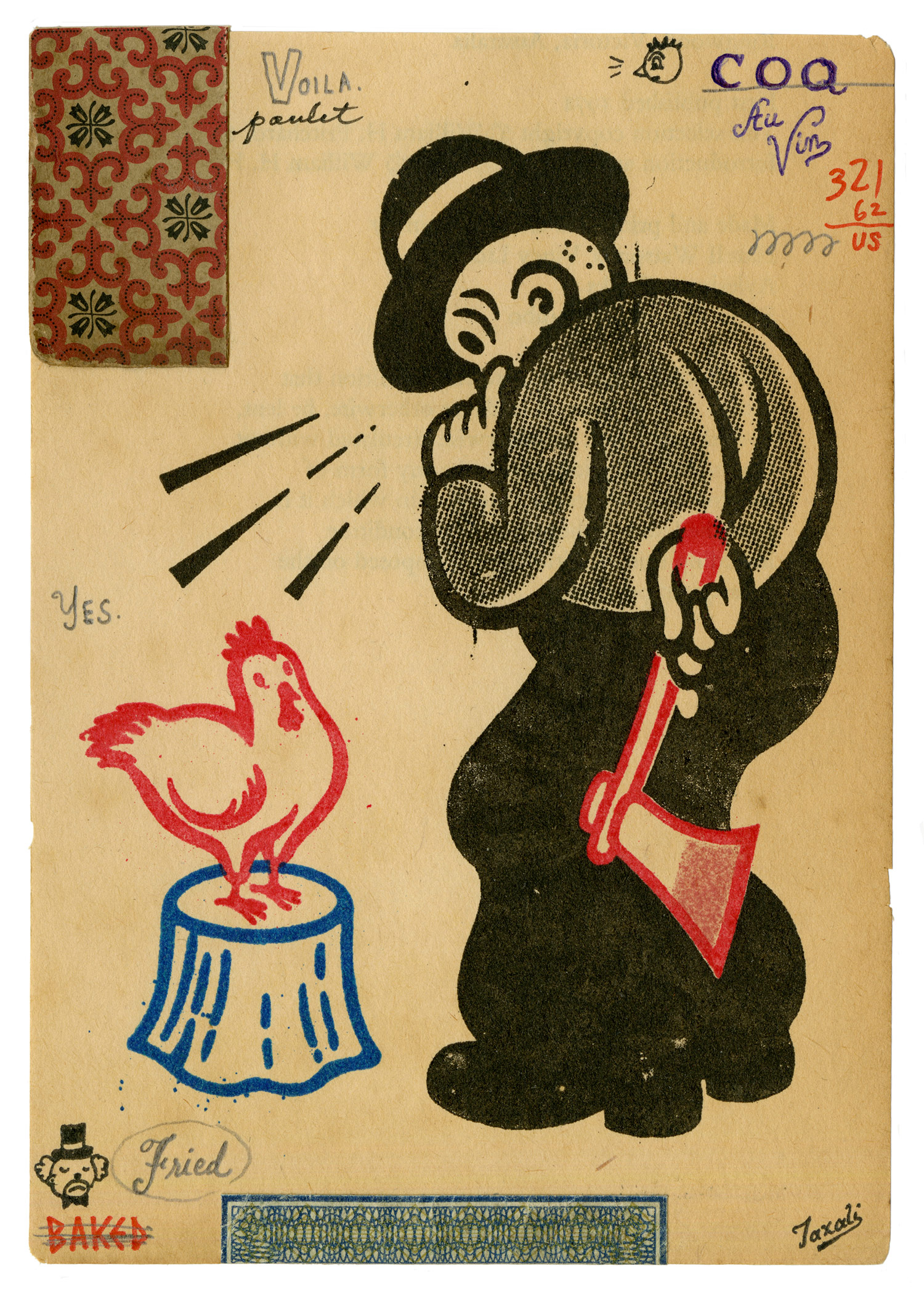

In regards to Indian culture, it’s such a big part of who I am, so I can’t help reflecting on that in my work. On weekends, my family would go to a place in Toronto called Gerard Street, which is Little India. We would go see Indian movies in the big theaters there, and everybody in the Indian community would show up; it was like one big party. I became enthralled by the relationship between the bad guy and the hero of those films; it’s something that’s always fascinated me. So in my career I’ve done a kind of sporadic series of Bollywood “bad guys”. They’re like composites of all these villains I saw in those films; people that don’t exist outside of my own head.

It sounds like you had a rich, cultural experience in Toronto, and were able to stay well-connected to the Indian community. I loved those days so much, but it wasn’t always like that; there weren’t a lot of Indians at that time. I remember being in the car with my family, and we’d see Indian people, and I’d be like, “Look! There’s Indian people!” (laughing) Imagine that now.

I went through a phase in art school where I engrossed myself in jazz music, and that sort of led me back to Hindustani classical. Like jazz, most of it is improvised, and is based on the reaction from the lead musician. For example, Ravi Shankar will kind of call the shots, and the other musicians will sort of look at him and jump into the raga, or the chord, that he establishes based on his mood from the reaction of the audience. When we’d go to India, I’d buy all of this Hindustani classical music—the old, traditional stuff.

“I fell in love with the Fleischer brothers who were doing Koko the Clown, and Felix the Cat, and Betty Boop…that era sort of found me. In a way, it just never left; I always imagined myself as an artist of that time.”

What about the past, and the classical, attracts you to continue looking there for inspiration? I think it’s maybe a combination of being born in the wrong time, (laughing) and looking at things that in any culture, or in any genre or form of art or design, has already been sorted out by people in the past. It’s also a combination of who I am, and where I come from, coupled with purely aesthetic things that have elements of nostalgia.

My father, for example, would buy me Mad Magazine compilations. I think he just saw that I really liked them, so he continued to get them for me. He would also take me to the library, and drop me off so I could spend a few hours there. I’d go straight to the comic book art section, and I fell in love with the Fleischer brothers who were doing Koko the Clown, and Felix the Cat, and Betty Boop. I think because of what my dad was introducing me to, and the things I was seeing in the library, that era sort of found me. In a way, it just never left; I always imagined myself as an artist of that time.

That’s interesting—so do you find that your mind goes to that same place now? Yes! I think it was a result of going to art school and veering away from that. And then learning at a certain point that the trueness of who one is is found in the endeavors of their childhood expressions, before you’re tainted and overly influenced by other stuff that’s cool or trendy. When I was in art school, looking at my childhood drawings and things, I thought, That was fun! That’s actually who I am. So I circled back to that, and continued to develop that aesthetic, which I love.

I remember my dad gave me a sketchbook; on the first page, it showed you how to draw Mickey Mouse, and the rest of the sketchbook was blank. I loved that. I thought, I’ve got this down, so now I’m going to do my own thing. The reverence for line in that sketchbook also really stuck with me. It’s a big part of my aesthetic; the solidity of the line, the weight of the line, the variations of the line, the strength of the line, and the communication of the line.

“When I was in art school, looking at my childhood drawings and things, I thought, That was fun! That’s actually who I am. So I circled back…and continued to develop that aesthetic…”

Was it during your art school years that you first started to grow more confident in that aesthetic? I would say it happened in my third year of school. I had this really great teacher named Jerzy Kołacz; a Polish illustrator. He taught me that having a personal voice, expression, and strong ideas is essential in art and illustration. So instead of looking at what other people are doing, find out who it is that you are, and express your artwork through that understanding.

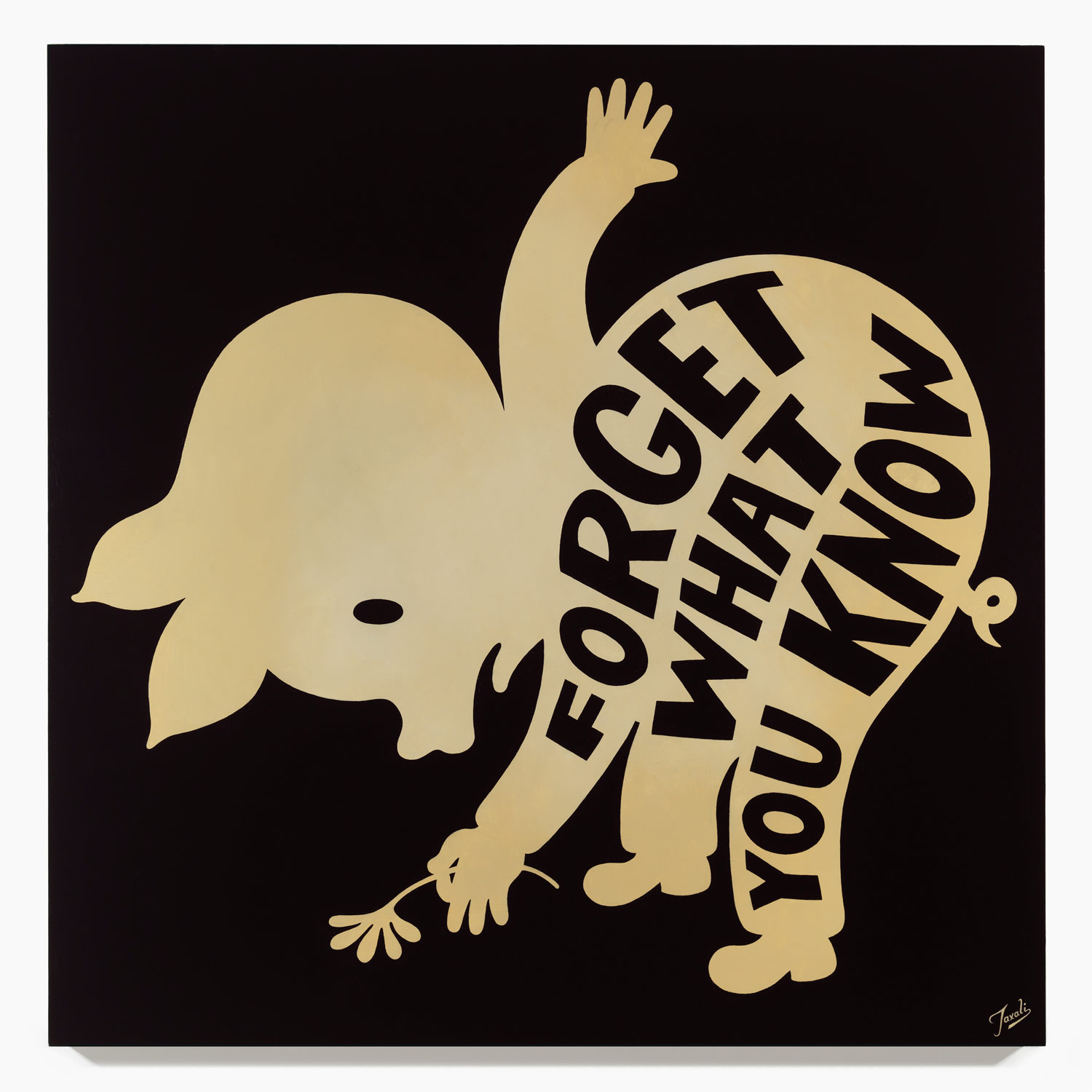

That’s great advice. When I look at your work, the voice is so strong, and clear. Do you feel like your work has social-political overtones? I think a picture is a means of engaging in a conversation with a viewer, so I’m hoping that it reflects who I am in terms of being somebody who has a sense of humor, and a bit of cynicism and whimsey about the way I see things. If the picture reflects that, then it’s reflecting who I really am. But it’s not always an accurate reflection—sometimes it’s mere storytelling; creating a narrative about something else. I think it’s okay to be detached from the subject matter, though, and to be honest about not knowing more about it. I don’t profess to be an expert on anything—I’m only a commentator. I don’t think anybody should claim to be an expert, because I think the more you know about something, the more questions you have. The conclusions you arrive at should be more about evoking a dialog than making final statements. That’s kind of an aggressive and hostile way to respond to the world.

I often think about that idea; of never hoping to become an expert. When there’s nothing left to learn, what else is there to be curious about? And why make something if you’re not curious? I wonder how that speaks to your role as an educator. When I teach a class, I’m there to help guide my students to the place they come from and who they really are, rather than telling them to look at a cool style and ask them to make their version of it. The idea I try to convey to them is that self-scrutiny is important—not of who you are, but of the picture you’re making—and to constantly ask questions about how you can make something better. Not in the sense of the surface aesthetic, but in expressing the most honest form of communication. The danger that I fell into, which I see a lot of art and illustration students fall into, is mimicking and replicating others. It’s an easy thing to do; you look at successful visual solutions and you think, Well, that kind of works—I can do that as well. All the while, you’re getting lost in the creativity and inspiration of others, versus finding out what it is you really want to say.

I strive to let my students know that the purpose of being an artist is to be as honest as possible. And I think the honesty comes from your reactions to things that are already inside of you. We all have opinions about stuff, but communicating that in a sophisticated manner, with originality and visual flair, isn’t easy. I tell my students that the way to reach that level is to just make lots of pictures with an understanding of being honest, and the more pictures you make with that motivation, I think you can achieve great success.

“Be unavailable to the world for 60 minutes, and just let the doing take over. Don’t think; just take a piece of paper or a brush and let the hand do the heavy lifting. Let it just make stuff.”

How does being an educator impact your own work? Oh, immensely. When I first started teaching, I realized that articulating my thoughts and ideas about how and why I do things, was essential. When you’re talking to a group of people, and they’re also asking hard questions about that kind of stuff, it makes you think about it in a way you never consciously thought about it before. When you’re teaching, you have to explain and rationalize why. And that rationalization process helped me find and adhere to certain principles in a concrete, structured way.

Even as a teacher, you have so much to learn from your own students. Do you still have mentors? Yes, mostly my friends, and fellow artists and colleagues, and people who I share exhibitions with who inspire me. But I don’t really look at the work of other artists in order to feel motivated to make art. I feel more motivated by engaging with the world—listening to music, or watching a film, or going for a walk.

And I don’t really follow artists on social media or Instagram. I follow my grocery store and my girlfriend. (laughing) But I don’t really look too much at what others are doing there; it’s a nice thing to do periodically, but I think it’s dangerous to do every day. It worms its way into your own creativity, and then it somehow just sits there. I think it could also have some unhealthy repercussions; especially when you’re trying to find yourself as an artist. If you’re motivated by mentorship in the form of guidance by others for too long, then I don’t think you’re going to take those personal risks where you’ll really fall flat on your face, but at the same time discover something new—you know?

Absolutely, I do. Especially in the form of social media; everything just starts to look the same. The digital medium all comes down to ones and zeros. It’s unnatural, and it’s an inorganic experience. Art should be an organic experience—like going to a gallery, or looking at a book, or watching a film in a theater.

“The idea I try to convey to [my students] is that self-scrutiny is important—not of who you are, but of the picture you’re making—and to constantly ask questions about how you can make something better.”

Speaking of looking for more organic forms of inspiration—you mentioned jazz, and its improvisational qualities. Do you listen to music while you’re working? I sure do. I think it may have been when I was an art student, but I read about the abstract expressionists of the New York School, and how the soundtrack for their art was jazz. It was something that helped motivate their visual expression. For me, it’s all about 1930s Delta Blues—it just makes me want to draw. When I hear it, I get goosebumps and shivers down my back. I can safely say that my last exhibition was devoted to the music of Mississippi Fred McDowell. While listening to him on repeat, amazing doors of my creativity opened up, and his music is what led me to those doors. His vocal expression, chord structure, rawness, and strumming of the guitar; pictures just came out of me like floodgates listening to that.

There’s so much depth of experience in those narratives—they’re very honest. Very honest. It’s such an amazing record of humankind and expression that comes from no pretenses other than a human being saying, “This is what’s inside me.” It’s incredible.

They hold such significance. Do you feel like you have a desire to contribute to something greater than yourself through your work? I don’t know. Maybe more so in the sense of being somebody who’s waving the flag for culture and art. I don’t really like to think about it, because it feels kind of narcissistic—as if the world needs me. I don’t think the world needs me. I think I just need to say things, and I’m lucky to be alive and to have the good fortune to live in a world that has granted me the opportunity to say them. I’m humbled by being alive, and by being who I am, and having the support of this amazing human experience. I think that there’s an obligation in terms of gratitude. And I think art should be revered, but it should never be put on a pedestal.

Was that the impulse for designing children’s toys or writing children’s books? The impulse was never really to reach a specific audience, because I find that to be a little bit contrived. Maurice Sendak feared children; he didn’t really even like to be around them. And both he and Theodor Seuss Geisel were vocal about not telling children how things are, because that’s condescending. When I wrote and illustrated my children’s book, it was for me. I don’t know anything about children, and I think any adult that professes to know what’s in the mind of a child is lying. The only thing that a human being knows is what they would have liked when they were a child.

But I don’t look at an audience, and try to figure out something they’ll like and then say, “Okay, this is for you.” The toys I made resonated with children, but they’re just based on my own working characters. It’s nice, and I’m glad when others see something that they enjoy in the work I make, but it’s certainly not by design.

“The danger…I see a lot of art and illustration students fall into, is mimicking and replicating others. It’s an easy thing to do…All the while, you’re getting lost in the creativity and inspiration of others, versus finding out what it is you really want to say.”

You’re making work that resonates with you, first. And that speaks to the experience you wanted to have when you were a child. Absolutely. I didn’t really like a lot of children’s books when I was growing up, because I hated being told how things are. (laughing) I hated those kinds of insincere lessons of morality and ethics. When I wrote my own children’s books, I vowed not to do that. I think it’s terribly patronizing when a book tells a child, “And this is why you should brush your teeth.” It makes me cringe. Don’t call that literature; call it what it is. Don’t sugarcoat it, because children see right past that.

I think we underestimate the power of Grimm’s fairytales, or Sendak’s beautifully dark world—they’re all about empowerment. And when children use their inner strength to achieve that empowerment, it makes for a really healthy reaction to the world. Sendak said it really well in his 1954 Caldecott speech—that if a child didn’t like his book, not to force him to read it. At the same time, don’t prevent children from reading the things they like. Whatever a child likes, you should encourage.

You’ve successfully channeled your own wide range of interests into the work you’ve done over the years. In addition to the toys and books, there’s also of course editorial and commercial illustration, fashion, fine art, and you even designed currency for the Royal Canadian Mint. What do you see as the thread that connects all of these projects? It’s surprising to me when I look back at all the different things I’ve done. In a way, it just kind of happened. I never thought when I started out that I’d be doing silk pocket squares or cufflinks for Harry Rosen.

I don’t get too caught up in the stuff I’ve done in the past because it already happened. There was a really nice answer that Pablo Picasso gave Gertrude Stein when she said that she finally understood what he was trying to do in a painting of his that she had been looking at for a very long time. He responded by saying that she was asking him to talk about a dream that he had a long a time ago. And you can’t talk about a dream you had a long time ago; it’s gone. It’s abstract, and it’s a faded memory. All you can do is shrug, and go, Okay, yeah, that’s what I see. At first, I thought he was just being sort of dismissive to Stein, but he’s absolutely right. When I look back at this stuff, it’s a bit foggy. It’s stuff I’ve done, but it’s buried in the past. The most important thing is process, not the byproduct of the process—that’s just a record. And I don’t think one should sit too much in contemplation of those records, because it can prevent you from moving forward.

“I don’t think creative satisfaction means doing everything that you wanted to do. I think it means giving it a shot every day, and doing the best that you can.”

What advice would you give an illustrator who’s just starting out? A person shouldn’t have unrealistic expectations about achieving the thing they love overnight. Maybe you have a full-time job, or are in school. You know, you have to pay the bills. But I think a person can do two things, every day. The first is to meditate, and sit in stillness; even if it’s for five to ten minutes. Your creativity doesn’t come from your mind, it comes from your essence. When you actively sit in silent observation and non-judgement, and just breathe, what you’re doing is calming and maintaining control over your mind. You’re not letting the ego take over. And when the ego doesn’t take over, you become a conduit for all of these amazing artistic ideas. And then great things happen.

A person should also draw or paint or sculpt every day, for at least an hour. I think everybody can find that amount of time; to be creative, to be unreached, and to turn off their telephones, and social media. Be unavailable to the world for 60 minutes, and just let the doing take over. Don’t think; just take a piece of paper or a brush and let the hand do the heavy lifting. Let it just make stuff. Also, try not drawing in a sketchbook, because a sketchbook is a book, and people feel self conscious about something that’s going to stick around, versus scraps of paper that they can always shred. You can feel safe, then, going to crazy places with your art and your expression.

The kind of satisfaction you get from just letting go. Do you feel creatively satisfied? Yeah! I like teaching. And I like my life. I don’t think creative satisfaction means doing everything that you wanted to do. I think it means giving it a shot every day, and doing the best that you can. Because the world is hard enough as it is, and society is structured such that we’re constantly being told what we should be doing. I think that’s a lot for human beings to bear.

There’s always the thing that could have happened, but didn’t. If I made a list of things that I almost achieved, and didn’t, it’s kind of depressing. (laughing) So I try to remind myself to just do the best that I can, and focus on the fact that I’m healthy and happy and alive.

“I don’t think the world needs me. I think I just need to say things, and I’m lucky to be alive and to have the good fortune to live in a world that has granted me the opportunity to say them.”