- Interview by Tina Essmaker January 24, 2017

- Photography by Elizabeth Weinberg

Geoff McFetridge

- artist

- designer

LA-based artist and designer, Geoff McFetridge, recalls his early love of drawing while growing up in Calgary, Alberta, what led him into the world of commercial design, how he’s grown on his own terms, and the importance of pushing past what stands in the way of creating.

Tell me about where you grew up and how your childhood influenced your ideas about creativity. I was born in 1971 and grew up in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. It’s directly above Montana. It was a smaller town, but, mainly, it was isolated at a time when isolation meant something.

The other thing about where I grew up was that I lived in the suburbs. I grew up in a housing development on the edge of the prairie, which went north to nowhere. There were mountains to the west. It felt like we were on the edge of everything. There are good and bad parts of growing up in a void—and everyone has their own version of the void. There’s nothing wrong with a lack of input, and I somehow ended up liking all of the same stuff that everyone else likes. I found ways to be inspired, and I grew a capacity for looking inward and being self-sufficient. I by far see the positive sides of growing up isolated.

My parents both worked full-time and I entertained myself. I was always encouraged to create stuff, but was pretty much left alone. Kids were expected to be autonomous. There was a lot of space and boredom.

I was going to use the word boredom. I had a lot of space as well while I was growing up in a rural area of Southeastern Michigan. I had to use my imagination, or be bored. So, what forms of creativity were you drawn to early on? Drawing was it. What’s interesting is to think about when I started to view drawing as art-making. For me, drawing had always been a way to play. I realized early on that if I didn’t have a toy, I could draw it. If I didn’t have an X-wing starfighter, I could draw one, and then I could draw more and have a fleet. Drawing started as a direct response to my boredom, and it was the root of everything. I didn’t have paint or anything to make color. My dad is a lawyer and I used his highlighters, ballpoint pens, pencils, and legal paper. My style is still the same.

Drawing also became my identity and how I told stories. I was the kid who drew. That equated to being the creative one. Our society’s understanding of drawing has positive and negative consequences. If you can’t draw then people think you’re not creative, which is a certain type of struggle—and because I could draw, people asked me to do anything creative. I was asked to do stuff for yearbook, create sets for school plays, and draw the logo on the wall in the gym. I remember thinking I wasn’t even that good, but I was willing to do it. I liked to do it. I could list kids who could draw as well or better than me, but it was clear that I liked it more, and I didn’t have anything else going on.

“What’s interesting is to think about when I started to view drawing as art-making. For me, drawing had always been a way to play.”

You’ve talked about your path after high school. You said that you wanted to find a way to draw for a living and that graphic design seemed like a way to do that and get paid. Yeah, I grew up in Canada and didn’t know any artists, which is why I didn’t become an artist right away. I discovered design on my own and invented what I wanted to do over time. I was open to it. I chanced into it through my interests in skateboarding and music. I was the art kid and that’s how I found my venue. I saw a void I could fill.

Then I went to art school at a local college in Calgary that had cheap tuition. There I was exposed to larger ideas and the art world. That was also luck.

Then you moved from Calgary to California to do grad school at CalArts. What led you to leave where you came from and go somewhere unknown? I was working and doing projects in Calgary, but I didn’t want to continue doing the same work forever. I needed to go somewhere else and be exposed to new things.

When you went back to school, what did you study? It was just commercial art. There were double doors leading into the department and one door said commercial and the other said art, so you walked right in the middle—boom! I love the term commercial art. I couldn’t fathom only making art. All of the stuff I was consuming was commercial and that’s what I wanted to make.

What were your first years out of school like, and when did you begin to feel more confident in your work? CalArts was great because it allowed me to have my own version of success. When I decided to go to CalArts, I stopped working and I stopped drawing. I went there to learn how to think in a new way. It really was perfect. When I graduated in 1990, I went back to where I left off, but my thinking was different.

I took a bad job at a design agency and made graphics for malls in LA because I wanted to save enough money to buy a computer. The day I had enough money, I quit. I worked out of a garage in West Hollywood and then moved into the house with a bunch of guys and set up there. My work became more related to LA, and I was designing skateboards for Girl and Chocolate. Through that, I met the Beastie Boys and started making their magazine, Grand Royal.

I had clear goals. I wanted to take the work I was doing in my sketchbooks and make artwork for shows so I could share the work with people. I wanted to do animation and film titles and continue to do graphics.

I want to go back to something you just said. Will you elaborate on what you meant when you said that your thinking changed while in school at CalArts? It was a grad program, but it was really structured. Every week, we got an assignment. In that way, it was more like an undergraduate program. Although my thesis was important, it was more about the series of assignments that we finished and critiqued every week.

It quickly gave me an understanding that there’s a way to talk about design from the point of view as designer as author. You weren’t just fulfilling the client’s needs. You were using design as a way to speak to higher ideas, almost as if the ideas you brought to the project were as important as the client’s needs. I could make jokes or references or take sketchbook ideas and put them into my work. That seems so obvious now, but at the time I didn’t understand that. It gave me a point in space to aim for that was just out of my reach.

At CalArts, I felt lucky because the students in my class were a really smart, diverse group of professional, established designers. I was younger than most of them because I came straight from undergrad. In critiques, my classmates talked about their work and it sounded interesting, but then I’d look at the work and it was so opaque that you couldn’t see those ideas unless they broke it down in critique.

My goal was to create work that was really clear. I pushed back against this aesthetic ugliness and lack of clarity of the time—it was the early ’90s era of messy illegibility. The first thing I wanted people to see was the idea. It was a personal challenge to do that within my commercial work—like a secret mission. If I took a project, I’d do five versions and the one that was pulled directly from my sketchbook and closest to my personal voice was always the best, and usually the one the client chose.

My first show was a poster show with work that was almost entirely pulled from my personal sketchbook or my commercial sketchbook of work that was rejected. It fulfilled a cycle of creativity in that the work generated more work. And my work was being seen, which was important to me.

You were injecting your style and ideas into your commercial work and you got away with it, which is a wonderful position to be in early on in your career. Yeah, it really was.

“People talk about having peak experience. I think what I’m always looking for is peak creativity. What’s the peak? When you’re inventing as you’re making—not just finessing.”

I want to jump ahead a bit. In the early 2000s, you started creating film titles and briefly pursued more work in Hollywood. Then you abandoned that pursuit because you realized that you were trying to fit into an existing system. You were one person and you wanted to stay small rather than grow to fit into the studio model. I think about this a lot because we want to grow in a way that feels right. How do you grow and continue to do the work, but stay true to who you are? Was that a conscious decision on your part? Yes, it was. What your work looks like and how it feels is a result of how it was made—those things are interconnected.

I was interested in making the movie titles because I was drawn to animation. Yes, I chose to stay small, but that didn’t mean I would never do movie titles or animation again. It meant two things: one, if I wanted to do animation, I had to figure out how to do it without getting investors and producers and growing into a studio, which I’d be running stead of doing the work. Two, I wanted to be doing the stuff I was best at, which was being creative. I wanted to be hired as an individual, but I wasn’t going to change the system or conform.

I saw that I could work directly with directors who knew me. If they knew me, then we were basically collaborating. So I chose to work with people I knew who made movies, like Spike Jonze or Sofia Coppola or Jake Kasdan, and along the way there became more people like that.

Then I asked what else I could do. For a time, I directed music videos and commercials, but later backed away from both. Where I finally ended up was drawing and animation. By saying no to all of this stuff, I looked inward and asked what I really wanted to do. It wasn’t about the no—it was about what I said yes to.

In retrospect, I was just making decisions. I wasn’t super thoughtful, but I had instincts. When you’re a small studio, you can only take on so much and that makes you more decisive. You’re forced into doing more pieces of the job so you learn more. It’s also important to note that my ambitions are antithetical to running a studio. People talk about having peak experience. I think what I’m always looking for is peak creativity. What’s the peak? When you’re inventing as you’re making—not just finessing. That’s what I want to do.

I like that you mentioned instinct. You know when it’s time to take the next step and grow and when you should just hang out where you’re at for a while longer. Yeah, there are many aspects that seem so mundane that effect what you make. For example, I found that with a bigger studio my thinking was bigger. Also, how much does debt get into the way of good art making?

Yes, and that leads me to the next question. For independent creators, money is challenging because sometimes you have it and sometimes you don’t. Work ebbs and flows. How have your beliefs about money changed over the years as your career has progressed? When I started my studio, I really wanted to buy a dirt bike. I needed $4,000. When someone called about a project, I’d ask about the budget and if they said $4,000, I’d say yes. It was dirt bike money. Money has always felt intangible to me. Thinking about it in terms of the dirt bike I wanted made it feel more real.

My parents taught me to work hard and be frugal, but I’m also boneheaded about money, and I think that’s partly good. It doesn’t hurt as much to say no to things, to lose out on a project, or to not get paid because I don’t see things in monetary terms. I’m not a hippie or nonmaterialistic—money just doesn’t register very strongly. Maybe that’s a defensive measure because if money rules me, then I’m not in control. But it feels like part of who I am and not a decision I made.

Over the years, I’ve become more comfortable knowing that I’m the expert when it comes to budgets, balancing my books, and making business decisions. I used to think, “Wouldn’t it be great to have someone to help me with this?” But every project is so different. It’s abstract and I’m trying to give it this empirical value of money. I trust that my instincts are right and I learn from mistakes. I don’t have a business partner going over the books. It’s just me. The goal is to keep going and to be happy. I ask myself, what are the best ways to get there?

“…as creative people, we feel like everything we do is shit, but that’s because there’s stuff in the way…If we never start, or if we pause because the work sucks, those things are still in the way.”

Do you feel creatively satisfied with the work you’re doing? Yeah, I think so. Totally? It is a process. Every year I get closer to the center. I don’t know where the center is and I may be way off, but I do the stuff I want to do anyway, whether it’s commercial or personal work. Then there’s the stuff I get asked to do—it’s great when people ask me to do work I would do anyway. I feel lucky.

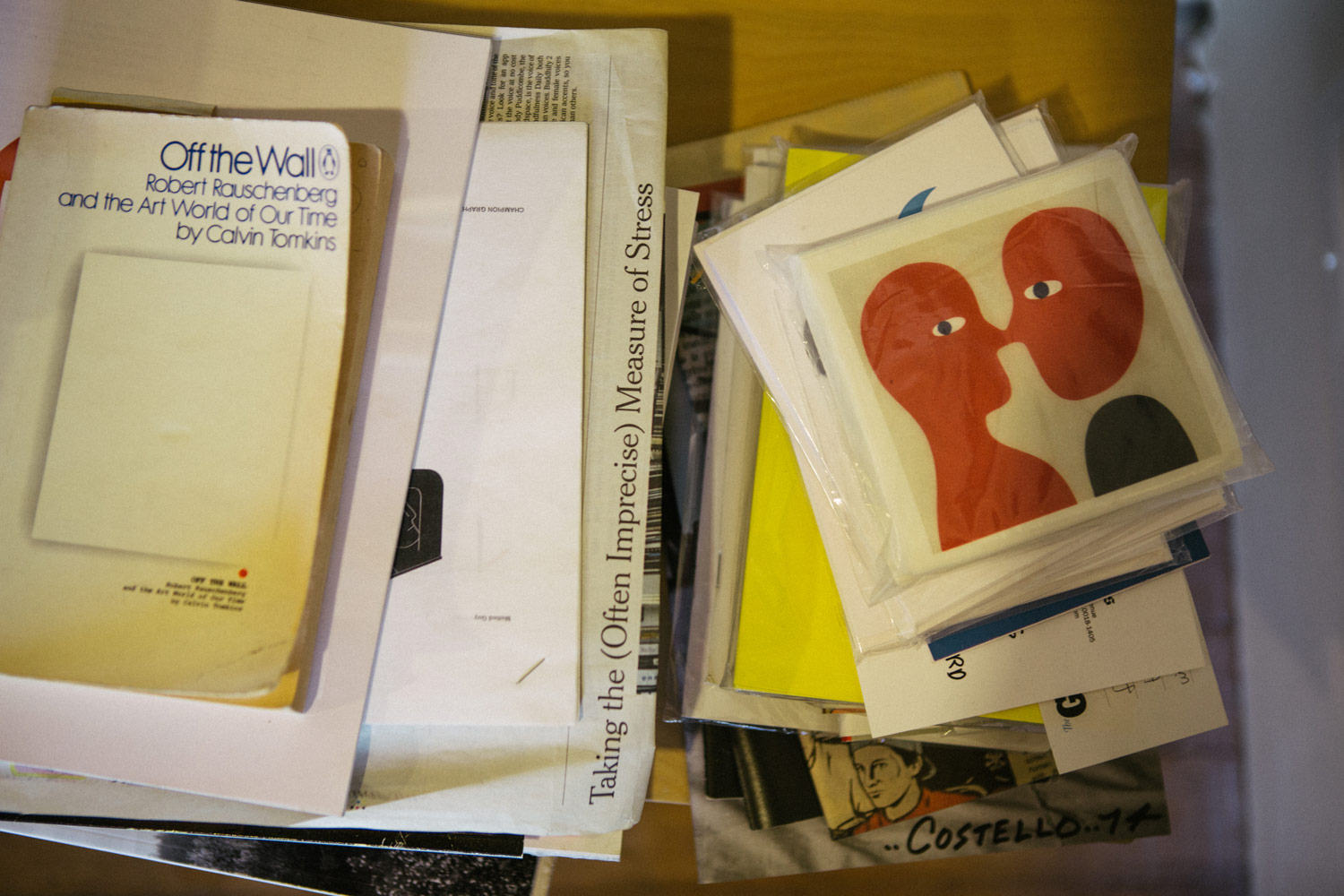

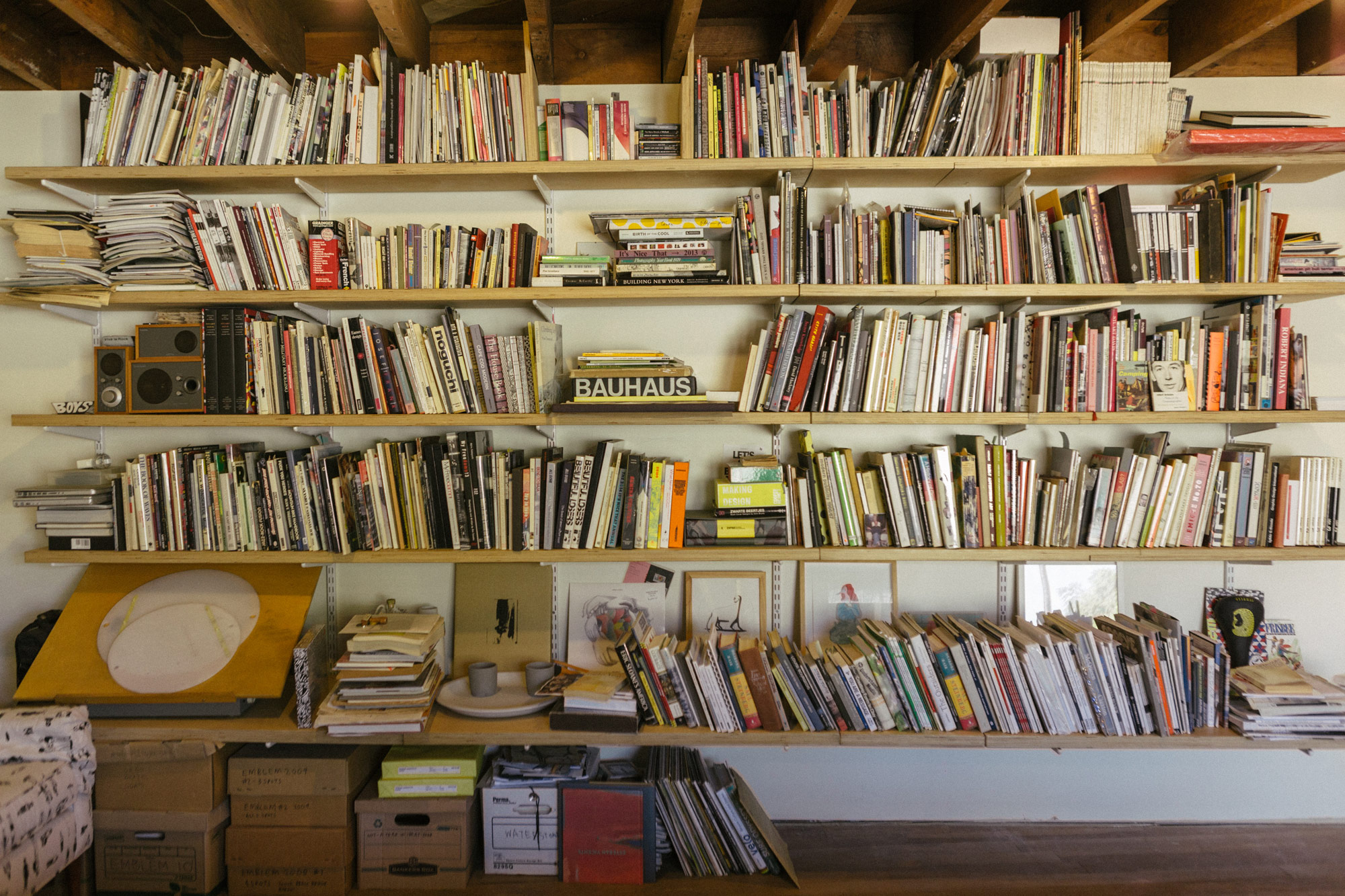

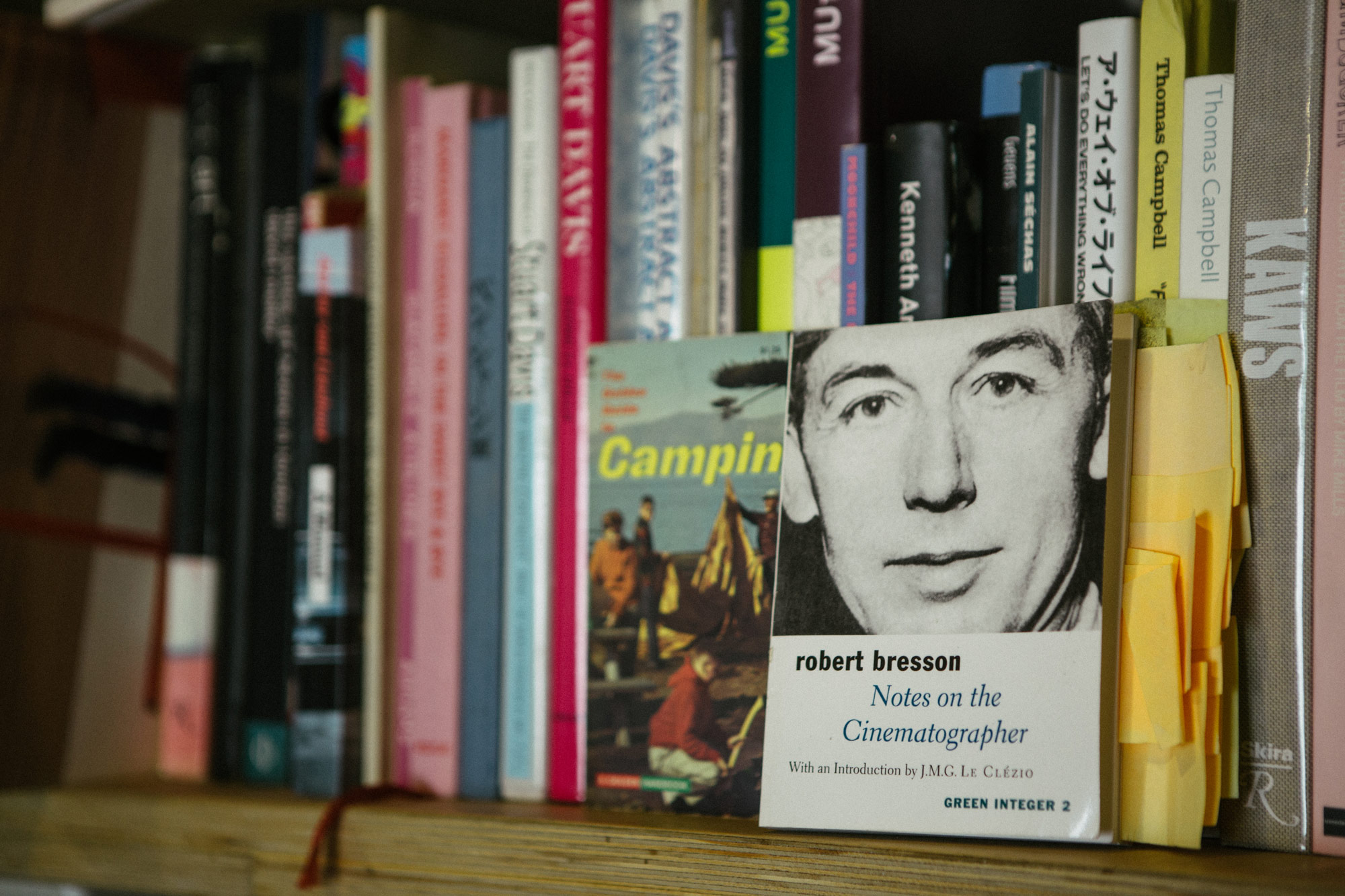

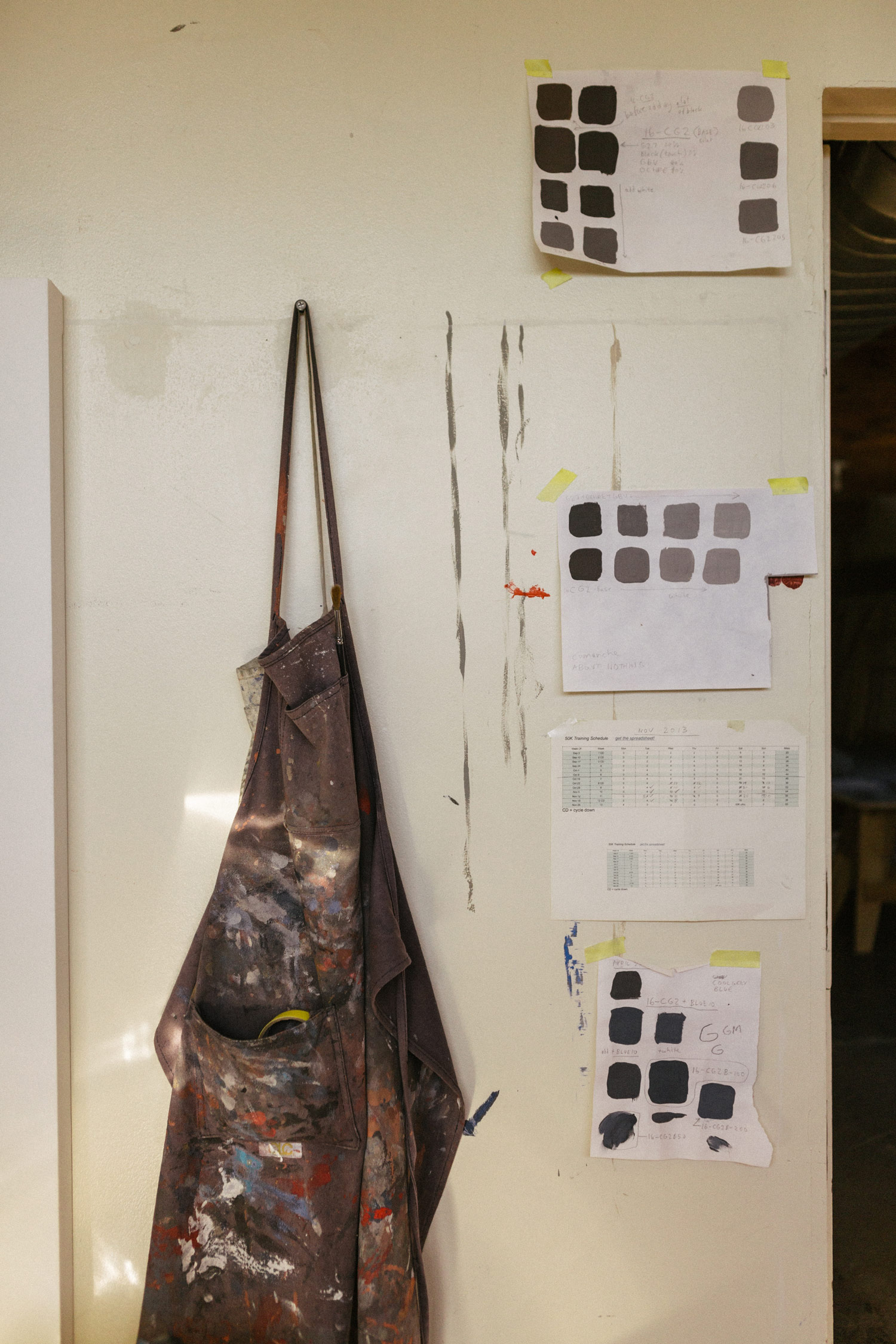

Do you split your time between commercial and personal work, or do they bleed over into one another? I do both and try to bring them as close together as I can. My studio is two floors and the upstairs has computers; that’s where I draw. Downstairs is printing and a front room for painting, so there is a separation. When I’m painting it’s intensive and absorbing because it physically takes a lot of time. I haven’t been painting since I did work for a group show a few months ago. Right now, I’m drawing and getting ready to paint.

Everything has come full circle for you. You were interested in drawing and art when you were young, but opted to do something more commercial. Now you work as a graphic designer and have incorporated fine art back into that. It is. My life has been binary, with all of these opposites coming together. I’m half Chinese and half Irish. I grew up in Canada, but my interests were rooted in other places. I lived in the suburbs, but behind my house was a prairie that went on forever. I went to school for commercial art and learned archaic techniques, like airbrushing and masking, that I now use to make art. And then I went to college to learn to think.

So much of my day is like, oh, that was the CalArts portion, or that was an Alberta College of Art moment. My thinking is conceptual, but then I am concerned about presentation and cleanliness, and I make work that’s very clean and handmade, like the early days of graphic production.

That’s cool. I want to ask you one more thing. It’s a new year and people are talking about resolutions. I don’t want to ask about that, but I do want to ask if there’s anything you would like to challenge us to think about in the new year as we move forward with our work. Whenever we start, there’s an idea that we have to search for content first. What will we draw or write? I have a feeling that it isn’t about researching or Googling stuff—for me, it’s about removing all of the ideas that are in the way of my thinking.

How do you remove those layers, those walls? I draw them out of the way. The things I draw aren’t only the things I want to draw—they’re the things I’m getting out of the way. That concept is about understating that, as creative people, we feel like everything we do is shit, but that’s because there’s stuff in the way—and that’s a good thing to recognize. If we never start, or if we pause because the work sucks, those things are still in the way. We have to keep going to get past them.

“What your work looks like and how it feels is a result of how it was made—those things are interconnected.”