- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker September 10, 2013

- Photo by Jason Varney

The Heads of State

- artist

- designer

- illustrator

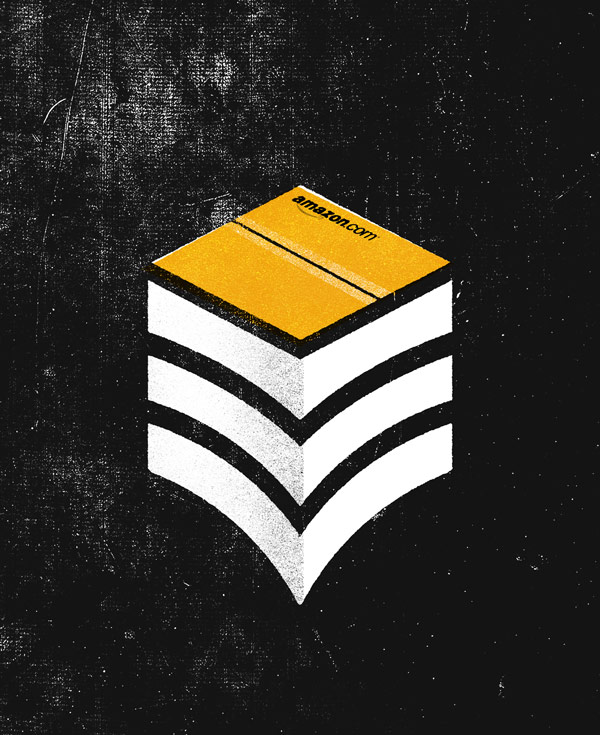

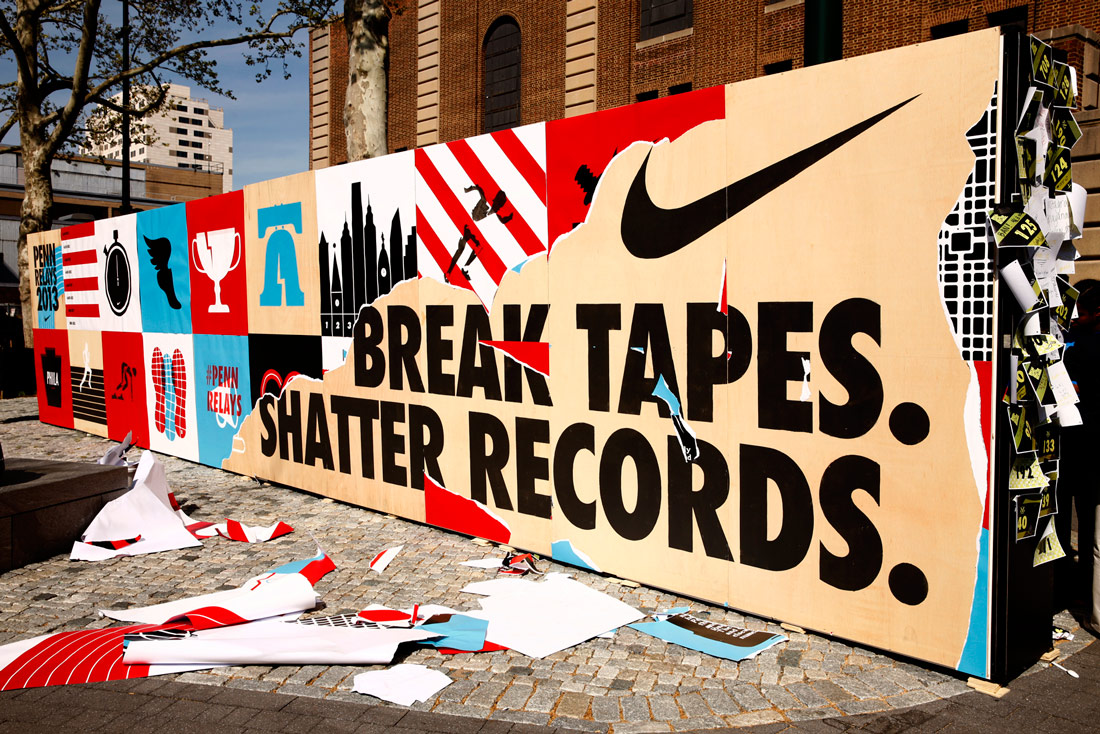

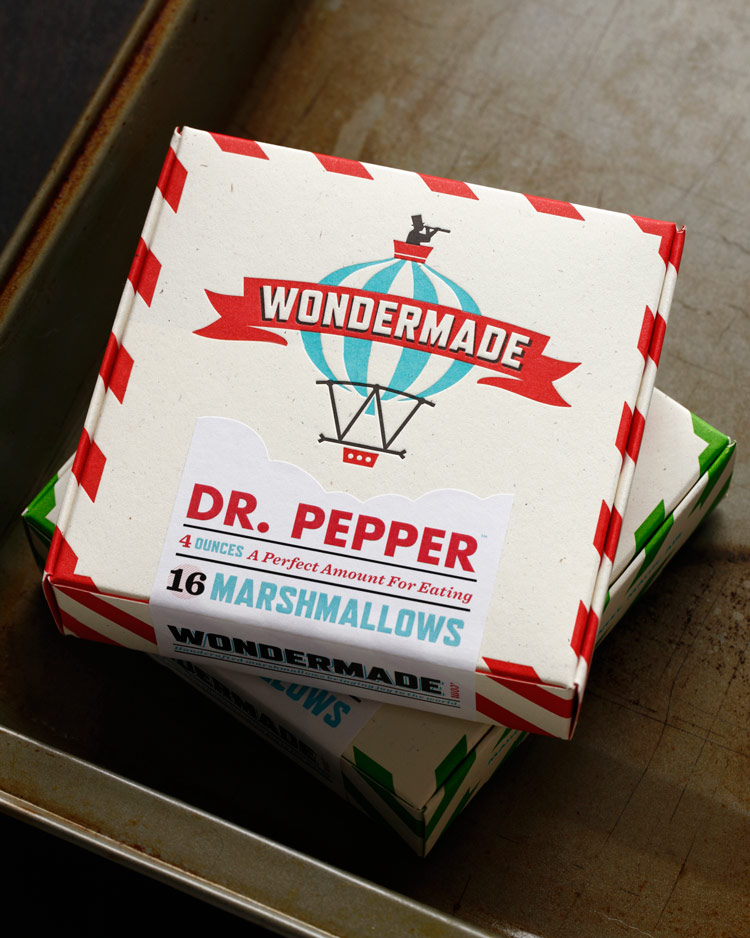

Jason Kernevich and Dustin Summers have been working together as The Heads of State for over a decade. They’ve created award-winning posters, book covers, branding, and illustration for clients such as Nike, the New York Times, Starbucks, Penguin, Knopf, the School of Visual Arts, and many musicians and artists. They lecture frequently about their work and process, and teach graphic design and illustration at Tyler School of Art, where they both studied.

Interview

Describe your paths to what you’re doing now.

Dusty: Jason and I went to Tyler School of Art here in Philadelphia in the late 90s and that’s where we met. We weren’t close friends initially, but the program was tight-knit and competitive, so we spent a lot of nights working in the lab together, which led to us getting to know each other’s work and forming a friendship. After graduation, I got a job at a book publisher here in Philly—

Jason: And I worked for a small design studio in town. Occasionally, Dusty and I met for lunch.

Dusty: After September 11th, the job market was in the tank. There were still jobs available, but nothing that we felt was super creative. We wanted to do fun stuff, so we met after work and made silkscreen concert posters. This doesn’t sound very original now, but not everyone was doing it at the time. When we started the collaboration, it was mostly so we could experiment; of course, we liked the bands, too. It was never about making money; it was a way to do the things we weren’t doing at our day jobs.

Also, our styles were completely different, which people are surprised to hear now. Coming out of college, my portfolio was super clean and vector; Jason’s was ultra hand-done.

Jason: I think graphic designers in general were still holding on to stuff from the late 90s at the time—the David Carson thing was still hanging around. We admired that work, but within a couple weeks of starting our day jobs, we knew that wasn’t what we wanted to do forever. Working together on the posters wasn’t so much about screenprinting as it was about being able to do something that was our own.

Dusty: We made posters after work at Jason’s apartment. It was 2001 and we had one computer with a dial-up connection. One of us manned Photoshop and the other drew and scanned in artwork, and we hovered over each other the whole time. I wish it was still like that sometimes.

Jason: What was so charming about it was that, yes, it was hard work, but it led to a lot of exciting stuff and graphic experimentation.

We sold the finished posters at shows and tried to make enough money to work on the next poster. We had some good connections with friends who put on shows and with people who managed venues because there was a cool, tight-knit music scene in Philadelphia. People were into what we were doing and it started to gain momentum. We started to get some recognition from the design community for the work around 2003 and 2004.

Dusty: We were still working full-time during all of this. Then in 2004, we decided to go to SXSW and that was a turning point. Back then, SXSW was much more music-focused and I literally found a notebook of contacts laying in the trash—it was full of contact information for bands and had over 10,000 names in it! We were like, “Holy shit!” At the time, we were 21 or 22 and had saved up $800. We said, “Fuck it!” and decided to spend that money to do a direct mailing. We printed out 16-page portfolio booklets and chose 1,000 names to mail them to. With direct marketing, you’re supposed to get a 10% return, so we expected to hear back from 100 people. One band responded: Wilco. This was when Yankee Hotel Foxtrot was out, which was a big album for them. We did a bunch of posters for them, they turned out great, and it paid really well. Plus, R.E.M. and Modest Mouse saw the posters and reached out for work. We started to get real clients and began to make some money. We haven’t done a lot of self-promotion; our work has continued to spread in that same way.

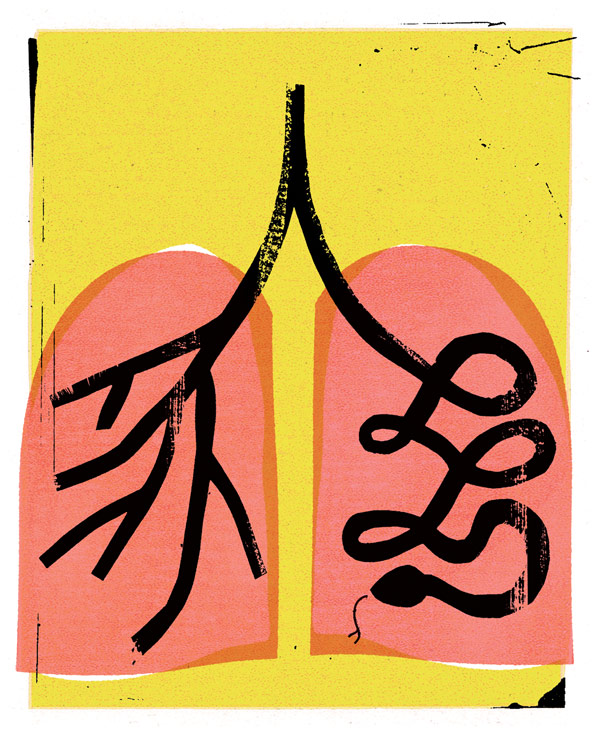

Jason: It wasn’t too long after that that Brian Rea and Nicholas Blechman from the New York Times reached out to ask if we would do an op-ed illustration. The knee-jerk reaction was that we weren’t illustrators and we couldn’t do it, but we knew the poster thing had a limit. We didn’t get into this to make posters or be poster artists. We were just trying to do something and hoped that that would lead to something else, which would lead to something else. We were struggling with a stint of restlessness—which I think we still contend with from time to time—so we ventured into illustration as a way to keep things moving into new territory.

Dusty: All of that led to getting a lot of illustration jobs.

Jason: It was at that point that we knew we could do it for real. Now, a lot of designers are also doing illustration, but at the time, it felt like a new thing for us to do both. I think we’ve been lucky to be able to turn the corner into new territory at the right time.

Dusty: When you’re doing illustration for so many years, though, it becomes what you’re known for. I think the last two or three years have been about us getting back to doing more design work as well. We dabbled in the posters, got our feet wet in illustration, and now we’re coming back to design—hopefully we can bring together everything we’ve learned over the past 10 years. Now, our new challenge is running a studio, and I’ve been enjoying the day to day process of that.

“We dabbled in the posters, got our feet wet in illustration, and now we’re coming back to design—hopefully we can bring together everything we’ve learned…” / Dusty

Tina: You guys have been at this for 10 years? That’s a long time!

Dusty: This year marks 10 years, but it feels shorter than that because we’ve done different types of work.

Tina: Yeah, that makes sense. So, was creativity part of your childhoods when you were growing up?

Dusty: I didn’t feel any more creative than other kids. I was an only child, though, so I spent a lot of time off in the corner, drawing.

to Jason You gotta tell ‘em about painting.

Jason: (laughing) I started studying fine art oil painting when I was seven. A family friend was an old-school portrait painter and I’d spend six hours every Saturday morning, studying with her in the studio, learning to oil paint. I did that into junior high and started to get into some bad stuff, like Thomas Kinkade-style barns and Bob Ross lighthouses. I had an oil painting studio in my grandparent’s basement and they now have some really embarrassing paintings of mine.

At some point, I got an electric guitar and stopped painting completely. Music became way more interesting to me and that became my focus. I think that’s where Dusty and I have similar experiences. He grew up in South Jersey and I grew up in Northern Pennsylvania, so we didn’t grow up as neighbors or friends, but we had similar cultural experiences—a skateboarding, basketball, hockey, Nirvana, Weezer, grunge upbringing.

Dusty: I think that’s how we both got turned on to design. I remember looking at album covers when I was 13 and can recall the smell of the ink on the booklet for In Utero. I knew that was graphic design, but it was more about the album and the beautiful artwork. I think that’s where my interest in design started.

Jason: Yeah. I made this fateful choice of wearing a Sonic Youth t-shirt to a guidance counselor recruitment. It had a Raymond Pettibon drawing on it and my recruiter said, “That’s Raymond Pettibon. He’s in the MoMa.” That made a connection for me that something could live in the punk and fine art worlds at the same time. Then, when someone at Tyler made a statement that the record covers Pettibon did for Black Flag were graphic design, that connected it even more for me.

Was what you two just described an “aha” moment for you?

Dusty: I think so. I was good at school, but I wasn’t into it. Art and design seemed like something I would be into.

Jason: It’s the same for me. I had an idea of what design and commercial art were, but for someone to point out that the records I already owned were design was an “aha” moment.

Have you guys had any mentors along the way?

Dusty: Definitely. During school, Joe Scorsone and Alice Drueding, who taught junior and senior courses at Tyler, were huge mentors for us. They instilled in us the idea that the concept is everything, and that’s really part of our process now. As important as aesthetics are, they come secondary to the concept. If you’re a good designer and know your medium, you can make anything look good, but if it just looks good and there’s no thought behind it, then it’s not that interesting to us. Joe and Alice mentored us in the way of critical thinking and and exposed us to design that was removed from what was going on at the time—if we hadn’t had them, our portfolios would’ve been David Carson ripoffs, (laughing) and I’m so glad that they weren’t.

Jason: Joe Scorsone, in particular, was a mentor to me. He comes from a traditional poster-making background and has done many great, classic posters. In addition to Joe’s influence on us, Tyler also has a heritage of poster and album design and we were taught that, fundamentally, design should be bold, clear, smart, and emotionally present. I think we’ve applied that without even thinking about it because of our education.

“We didn’t get into this to make posters or be poster artists. We were just trying to do something and hoped that that would lead to something else.” / Jason

Has there been a point when you’ve had to take a big risk to move forward?

Dusty: That’s part of the story we didn’t tell. When we started doing the posters for Wilco, we were trying to figure out what we were going to do for the rest of our lives. I had decided to move out to Seattle with my wife, just to get a breath of fresh air. Jason and I figured we’d do some work together every now and then, but we didn’t think we were going to do Heads of State full-time.

Jason: We didn’t expect it to turn into a design studio; we expected it to be an inspired collaboration at most. Dusty had moved to Seattle and I was freelancing and living in New York. We spent three or four years living on separate coasts while the business was gaining momentum.

Dusty: It got to the point where we were both working 18-hour days between our full-time jobs and Heads of State.

Jason: At that point, the risk was deciding to quit our full-time day jobs and to move back to Philadelphia to have a proper studio and learn to run a business. Coming from a creative background, we just wanted to make stuff and running a business didn’t come easily. That was a big risk.

Dusty: Yeah. We quit the full-time jobs, gave up the 401k, and moved across the country to Philly. We got an office and hoped that people would keep calling.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Dusty: Absolutely. My wife knows that this is what makes me happy. At times, it’s super stressful and I can get to the point where I don’t want to make images anymore. But at the end of the day, it’s inspiring and I don’t want to do anything else.

Jason: I’m probably going to regret saying this, but I don’t feel like much has changed for me in the last 20 years. That sounds crazy, but right over there is my desk, which you can’t see. On top of it, there are a couple sketchbooks, a stack of old books, a few magazines, scissors, an X-Acto knife, tape, and a scanner. Twenty years ago, my bedroom probably had all those same things, except I was using a photocopier to make a demo tape for my high school band instead of making it on the computer. Anybody who knows me, family or otherwise, knows that I’ve always been doing a version of this.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourselves?

Dusty: Um.

Jason: Somebody asked us this recently. I think we do?

Dusty to Jason: Yeah, but if you say yes, then what do you say after?

Jason to Dusty: Well, we both teach.

Dusty to Jason: Okay, there you go. Good way around that.

Jason to Dusty: Well, it’s true.

Dusty to Jason: But when you say something bigger, it feels like it has to be something bigger than graphic design.

Jason: I’ll just say that we both teach and that’s really important to us—maybe the most important. Selfishly, it makes us better thinkers, communicators, and designers. It’s pretty cool because we teach at Tyler, where we studied. There are moments when I can recall the voice of a professor who taught me something that I’m now passing on to a student. That’s a great feeling, and it does feel bigger than me or us.

In terms of charity stuff, we try to do a fair amount of pro bono work when we can fit it in.

We’ve also tried to become more involved in what’s going on around Philadelphia. When we first moved here, we were more interested in keeping our heads down and doing our work. The city can be very cool and inspiring, but also very provincial; it’s a big city, but a small town. Now that we’ve been here for a few years, we feel more connected to the neighborhood and things that are going on. For example, we’re going to be involved in branding and helping to usher in a community park, which is great.

Dusty: As we do more and hone who we are as a studio, it’d be great to make that path more about giving back. It always feels good to sit down and design something that’s not for the next big thing or company. It’s important to supplement client work by spending time on things that allow us to give back.

Tina: Teaching is a lot of work, but can be really rewarding. Also, after talking about everything you guys do, I can’t believe you have time for it all.

Dusty: We don’t have the time! It’s a constant problem because there’s so much we want to do. It does seem to work out, though. Because we’ve been working together for over 10 years, there’s a lot of shorthand that goes on between us, and I think that saves time. We work fast and can hammer out ideas pretty quickly—some of our best work doesn’t take as long as one would think it should. I also think that’s part of being restless; we’re always trying to figure out what’s next.

“As important as aesthetics are, they come secondary to the concept. If you’re a good designer and know your medium, you can make anything look good, but if it just looks good and there’s no thought behind it, then it’s not that interesting…” / Dusty

That actually brings us to our next question. Are you creatively satisfied?

Jason: No. Never! I’m fucking creatively miserable at the moment. (laughing)

Dusty: I think that as we get older and don’t have as much energy, we’re not going to work 18-hour days—we’re in our mid–30s, so it’s just not going to happen.

Jason: We’ve been trying to do this thing where we alternate taking a week off. One month, I get a week off; the next month, Dusty gets a week off; the following month, Woody, our designer, gets a week off. There are requirements in terms of a goal for the week—we have to set milestones and write about what we do. It’s like a mini-sabbatical or workshop and we think it’s yielded some of our best and most creatively satisfying stuff. We see that as a huge part of what we’ll do moving forward, but at the minute, we’re just buried in stuff—we’re both overdue for a week off.

Dusty: It’s also really hard to be continually inspired by graphic design after 10 years. We find inspiration and satisfaction outside of work, too. Jason is really into cooking and I like building bikes; I’m not good at it, but there is a creative release in doing it. While I’m working on a bike, I get to think about something other than design and no one is going to judge the aesthetics. It’s about rejuvenation, I guess.

Is there anything that you guys are interested in doing or exploring over the next 5 to 10 years?

Jason: I’m working on a project now that I’m doing some writing for and I’m really enjoying it. I’d like to do more writing over the coming years, whether it’s a book or project. That’s a personal goal.

Dusty: As far as the company goes, being able to steer our own boat is important. We still get looked at as the guys who do posters, although we haven’t done them in five years, or we’re “the guys who do the illustrations.” We still do illustration, but there’s a huge amount of work that people don’t see, which is probably our own fault because we need to update our website. For a lot of our career, we’ve let the clients dictate who we are; moving forward, we want to dictate who we are as a company.

Jason: That’s the plan.

Tina: You probably give a lot of advice to your students as you’re teaching, but if you could give advice to a young person starting out in design or illustration, what would you say?

Jason: I think students need to do much more research. They’ve seen everything—I can’t show any of my students something without them already having seen it on Pinterest or Twitter a thousand times—but they don’t know who did it, and they don’t know what came before or what it influenced. The research and historical aspect of graphic design is really getting lost. That’s not as much of how-to-build-your-career advice; it’s about how to be better at what you do and I think that’s very important.

Dusty: I would say hang up the mouse for a little bit. These kids have now been using Photoshop and Illustrator since they were in middle school. The stuff that they’re doing in our classes blows us out of the water as far as technical savvy and actually making things look pretty goes. But there is that lack of knowledge and lack of experimentation. Everything is so immediate and insular, and it’s easy to lose a view of the broader range of graphic design. I used to subscribe to all the blogs and now I’ve culled it down to two or three design blogs that I’ll look at once a month, because it’s just too much. You have to put the blinders on a little bit.

Jason: We really employ this sense of quiet when it comes to that stuff. It’s easy to get pulled in directions if you’re not careful when you’re looking for inspiration. As you get older, finding inspiration in different places is important.

I think some people coming out of school could use a little more diversity in their life, too. So many kids now have that graphic design addiction: they come out of school and they’re just promo monsters–just crazy about it, you know? You really need to have more of a diverse life if you’re going to make good work.

Dusty: Yeah! They’ll know all the plugins and have 70,000 friends on Twitter, but they haven’t seen Ghostbusters. It’s about being culturally aware, not just design-aware.

On the flip side, it’s great when you see a student or a young person really embrace all this technology that’s available to launch some crazy curated website or launch their own project. Ten years ago, coming out of school, there was no chance you would have been able to do that. It’s really inspiring to see those kids who will not only do the design, but they’ll buy the website, and set up a Shopify store, and do something really great. That turns on this other part, this entrepreneurial spirit. If I’m going to look at somebody’s portfolio, that’s great. But let’s see the rest of your résumé and that you’ve gone and done other things.

“…I think the times when I have felt more immersed in a design scene were probably my least productive…I like a really diverse network of friends. That’s inspiring to me.” / Jason

How does living in Philadelphia impact your creativity?

Jason: What inspires me about Philadelphia is that, in terms of a scene or networking, nobody gives a shit. Like, nobody cares.

Dusty: (laughs)

Jason: I don’t mean that they don’t care! What I mean is that they care about good work. They don’t care about schmoozing. I’m not going to go out and rub elbows to succeed—it’s not going to work that way. No one likes that. It’s very low-key and understated in that way. You just have to put your head down and do really good work.

Dusty: Yeah, there’s much more of an honesty about this city. I think that comes from the working-class kind of history.

Is it important to you guys to be part of a creative community of people, and do you have that?

Dusty: No, not for me. I would be happy in a cabin in the woods with an Internet connection so that I could send the files in. But I think as a company, it is important to have that community around you.

Jason: I’m not quite as much of a, uh—

Dusty: Miser?

(all laughing)

Jason: I’m not as much of a miser, or isolationist, as Dusty might prefer to be.

Dusty: Yeah, I need an Internet connection and a Netflix account, and I’m good.

(all laughing)

Jason: I really like to be part of a community and a network, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be graphic designers. In fact, I think the times when I have felt more immersed in a design scene were probably my least productive. I like being able to have friends who are writers, or photographers, or chefs—I like a really diverse network of friends. That’s inspiring to me. It doesn’t have to be a design scene by any stretch.

Dusty: I’m not going to go back on what I said, but I think that’s important for your whole career. We had a network of friends who we knew when we were in our twenties and then we left for five or seven years before coming back. Now, we’re all in our thirties and we meet up with friends or acquaintances who say, “Hey, I’m starting this bar,” and we can say, “Awesome! We do graphic design. We should hook up.”

Jason: Yeah, we do have a fair amount of connections that trace back to those early days of poster-making because everyone in the music community started from the same creative place, or at least a desire to make something for themselves. Somebody is an entrepreneur or works at an ad agency or started a barbershop or works for a nonprofit, and they look to us to be a part of whatever they’re doing. Ten years ago it was, “Make a logo that I’m gonna put on a hoodie for my band,” and now it’s, “Make an ad campaign for a cultural alliance.” It’s cool in the way that it has grown. Community is very important, but it’s definitely not like a networking thing. It feels more like a support thing.

Dusty: That, again, speaks to the kind of small-town feel of Philadelphia. I think people tend to stick around here, whereas in New York or San Francisco—the more cosmopolitan cities—people hop back and forth. They might go out there for a job, then work in three agencies there, and then hop back. I think that’s one large benefit of Philly.

Very cool. What does a typical day look like for you guys?

Dusty to Jason: Do we tell the truth?

Jason to Dusty: You tell yours; I’ll tell mine.

(all laughing)

Dusty: We have such a small studio—there’s three people and a couple interns—so we’re able to dictate our own days a little bit. I’ve got two small kids, so I come into the office super early around 6am and leave at 3pm to pick up my kids. If I was at a larger agency, that wouldn’t happen. That’s why it’s great being my own boss and working with a small group of people—I’m able to live my life the way I need to.

The first couple hours of both our days is all admin work, which is the underbelly of graphic design. Then we have some solid hours of designing at the end of the day.

Jason: Jumping off of that make-your-own-schedule kind of thing, which we enjoy, I learned a long time ago that I’m pretty much worthless between 1–3pm. I can’t get anything done.

Dusty to Jason: That’s a big chunk of time!

Jason: Well, I make up for it because I get a lot done in the mornings and the evenings. In the middle, I do admin stuff or exercise or take a long lunch to recharge my battery. Then I’ll often work from 4–9pm when things are a little quieter.

Dusty: I think that stems from doing our early stuff after hours. If that’s when you’re most creative, then why do you have to be there 9am–5pm?

Jason: Yeah. What we’re not admitting is that we still like to keep freelancer hours sometimes. We’re not always able to do that, but, ideally, we get to have a lot more freedom. Compartmentalizing our tasks has become really valuable for us. If there’s admin work we can do at a coffee shop in the morning, then we do it; if there’s sketching we can do at a park for a couple hours, we do that. Working in that way has helped us recharge our batteries.

What are you guys listening to right now?

Jason: Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Willie Nelson, Talking Heads, and the Chromatics. The Band is on all the time, too.

Dusty: There’s always some Beach Boys and Willie Nelson, and there’s usually a steady flow of middle-career Dylan and grunge stuff, like Soundgarden.

Jason: As Dusty said, we definitely like the mid-career Dylan albums, like Desire, Self-Portrait—

Dusty: Planet Waves—that is a very under-appreciated album.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

Dusty: Dances with Wolves.

Jason to Dusty: That’s the one?

Dusty to Jason: Absolutely. What have you been watching?

Jason: The movie I watch the most is All the President’s Men—I think I wanted to be a newspaper reporter at some point. I also like Chinatown and Ghostbusters. There are some good theaters nearby, so it’s not like we’re not caught up on cinema. But all I seem to watch anymore are snow day movies, like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Police Academy 2.

Nice. So, do you have a favorite book?

Jason: I reread Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist a lot. I did a thing for a while where I only read classic cookbooks. I like Graham Greene. There’s a George Saunders book called Tenth of December that I read and it blew me away.

Dusty: Tinkers by Paul Harding is my favorite book of all-time. It’s about a kid who grows up in a cigar shop in 1800s New York and goes on to become a big time hotelier. Right now I’m reading Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather and it’s the best writing ever—it’s really beautiful. I also like nonfiction adventure, like Skeletons on the Zahara: a True Story of Survival and Undaunted Courage by Steven Ambrose.

What is your favorite food?

Dusty: Fresh ravioli. It’s a comfort food for me.

Tina: What constitutes “fresh” ravioli?

Dusty: Not frozen.

Jason: I really like Southeast Asian food—Malaysian, Vietnamese, Indonesian. I could be happy eating Southeast Asian street food forever.

What kind of legacy do you two hope to leave?

Dusty: I would want somebody to look back at our work and say, “That was honest and heartfelt.” We try to have a handmade element in most of our pieces so that they look human, even though there are portions that are done on the computer. That’s important to us—that the work looks like it was labored over and that we made conscious decisions about it.

Jason: I agree with everything Dusty said, but I’d like to add to it. We had a Christmas party with family and friends this year and I had a moment when I felt this appreciation for everybody who was there. What’s so cool about our business growing is that we get to work with some of the greatest people, and I’m super proud of that. I’d like part of our legacy to be that other people will say, “Those guys were really cool to work with, they were a cool family business, and everyone they brought on board was an honest, good person.”