- Interview by Tammi Heneveld August 9, 2016

- Photo by Daniel Arnold

Jean Jullien

- designer

- illustrator

Jean Jullien is a London-based graphic artist whose distinct style spans illustration, animation, installations, apparel, and more. He has worked with clients like The New Yorker, Nike, BMW, Uniqlo, Colette, and the New York Times. He graduated from Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art before co-founding the animation studio, Jullien Brothers, with his brother in 2011.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now. Like a lot of people, I grew up drawing and became very passionate about it at a young age. After high school, I became interested in studying animation and comic books, but because of the way the French educational system is set up—and because I wasn’t such a great student—I didn’t get into the art schools I wanted. Instead, I ended up enrolling in a very practical graphic design course in Brittany, the area I’m from.

While at school, I met some good people and was exposed to a lot of different cultures. I learned the crafts of image-making and communication, which were quite unknown to me before then. Graphic design showed me that there is a whole different aspect to image-making outside of entertainment or gallery shows. There is a certain practical aspect to it that is engaging and interesting to me.

After graduating from school in Brittany, I moved to London to carry on studying graphic design at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design in 2008 and, afterwards, the Royal College of Art in 2010. While still in college, I began to do commercial work alongside my regular school work. I’ve continued my commercial practice since then, which I juggle with personal side projects.

Was creativity part of your childhood? Were your parents in creative fields? Yes. When I was growing up, both my parents were in creative jobs. My mom is an architect and curator, and my dad’s a city planner. That said, I don’t know if they necessarily encouraged my brother, Nicolas, and I to go into creative jobs, but I don’t think it was discouraged either. They helped us grow into whatever we seemed to be interested in at the time; they were supportive without pushing us.

My parents definitely introduced me to a lot of culture. My dad was keen on French bandes dessinées (comic strips) and music, which probably had something to do with my brother becoming a musician later on. My mom was very interested in architecture, product design, and classic and modern art, which she introduced us to.

Your design work has a strong illustration element to it. How did that evolve? I was always more focused on graphic design, but I ended up doing illustration in a convoluted way. I started using a brush pen to break free from working on a computer all of the time and to experiment creatively. I felt quite comfortable with it and could draw letters as well as characters. That’s when I realized that the practice of illustration and graphic design aren’t necessarily exclusive. I also discovered designers like Alan Fletcher, Saul Bass, and Paul Rand, whose work all had a great sense of playfulness and a tactile aspect that I was really fond of.

Was there a specific “Aha!” moment when you knew that you’d pursue a creative career, or did you consider other options? By the time I moved to London, I was pretty sure I wanted to do something related to graphic design. But before that, I was seduced by the idea of pursuing journalism. There is a certain aspect of my practice that isn’t too dissimilar from that, though: a lot of my work is based on observation and current events.

I’ve known I’ve wanted to do something creative for a while—what specific shape it would take when I started, I never knew, and I still don’t. Something that is quite dear to me is experimenting with new mediums and techniques to see how much of my creative identity I can retain while also distorting it as much as I can. I like to play with my creativity and give it different shapes to see how far I can stretch it until it breaks.

“Graphic design showed me that there is a whole different aspect to image-making outside of entertainment or gallery shows. There is a certain practical aspect to it that is engaging and interesting…”

Is your desire to experiment within lots of different mediums part of the inspiration to start the animation studio, Jullien Brothers, with your brother in 2011? Yeah, and I also enjoy collaborating with brands for that reason, too. Jullien Brothers became a great way to experiment and try new ventures alongside, rather than in opposition of, what my brother and I were already doing on our own.

He and I have a good balance in the sense that he pushes for more drama-based work about serious topics and stories, while I focus more on playfulness and comedy. Nicolas and I are working on a TV series together right now, and we just finished a music video. We’re creating more work now than ever, and I really enjoy it.

Did you work a day job when you were starting out? I worked in the café at Central Saint Martins while I was in school, but I never had a “proper” day job after graduating—I went from studying to doing what I do now quite progressively. That said, it definitely took some time for me to secure enough substantial commercial work to do design full-time.

So you jumped into having a freelance commercial practice right out of school? I actually started when I was still in school. In those days, it was the beginning of the blog culture, so I began posting work I was making at school on MySpace. Soon after, a blog called Manystuff found my blog and did an article on it. That started the snowball effect that characterizes blogging and social media today: as more people shared it, I started to get commissions.

I never really felt like I had to intentionally start a freelance design career—I just continued sharing my work and accepting jobs along the way. I worked on professional projects with clients and kept schoolwork as a playground for my creative experimentation.

“Experimentation is something I’ve found to be very helpful…If you stick to doing the same thing, then eventually that’s all people will ask you to produce, which is going to be boring for both parties.”

How did doing commissions in school evolve into landing bigger and bigger clients after graduating? I was consistent with creating and sharing my work. I wanted to keep doing commercial projects to earn a living, but I also made sure to try different things within my personal practice and collaborate with others. Through showing diversity in what I could offer, I think that encouraged diversity in what I was being offered to do.

Experimentation is something I’ve found to be very helpful. Someone can see my small laboratory of ideas on social media and ask me, “This is really cool—can we do something along these lines?” If you stick to doing the same thing, then eventually that’s all people will ask you to produce, which is going to be boring for both parties.

What was the first big project that made you feel like a professional? I don’t think doing big projects or working with big companies was what made me feel like a professional designer—it was the fact that someone trusted me enough to ask me to create something for them. That was the first time I really felt like I was stepping out of my own cocoon, which had been comfortable and relatively risk-free.

That said, there were two projects that helped develop my appetite for pursuing more commercial work. The first was creating an image for Manystuff, the blog I mentioned, and the second was for a friend at Central Saint Martins, Rubin, who was a DJ. He set up a club night called Cliché, and I did the visual identity and posters for it. I liked having people put their trust in me and seeing people’s reactions to my posters on the wall. It was very exciting.

When you first started your commercial practice, did you have any mentors who showed you how to handle the business side? Were those things you were learning in school at the time, or did you teach yourself? It was a mix of a few things. I signed with an agent early on, and he was quite helpful in telling me how advertising companies and clients work. My teachers were also helpful, but I’ve found that exchanging ideas with peers and learning the trade as I go has been very beneficial as well. In that sense, I didn’t necessarily have a mentor, per se, but I had a group of people around me, and we have all taught each other.

“If you become too influenced by others or worried if people will accept your style, you might not seem confident, and I don’t think anyone wants to hire someone who isn’t confident…”

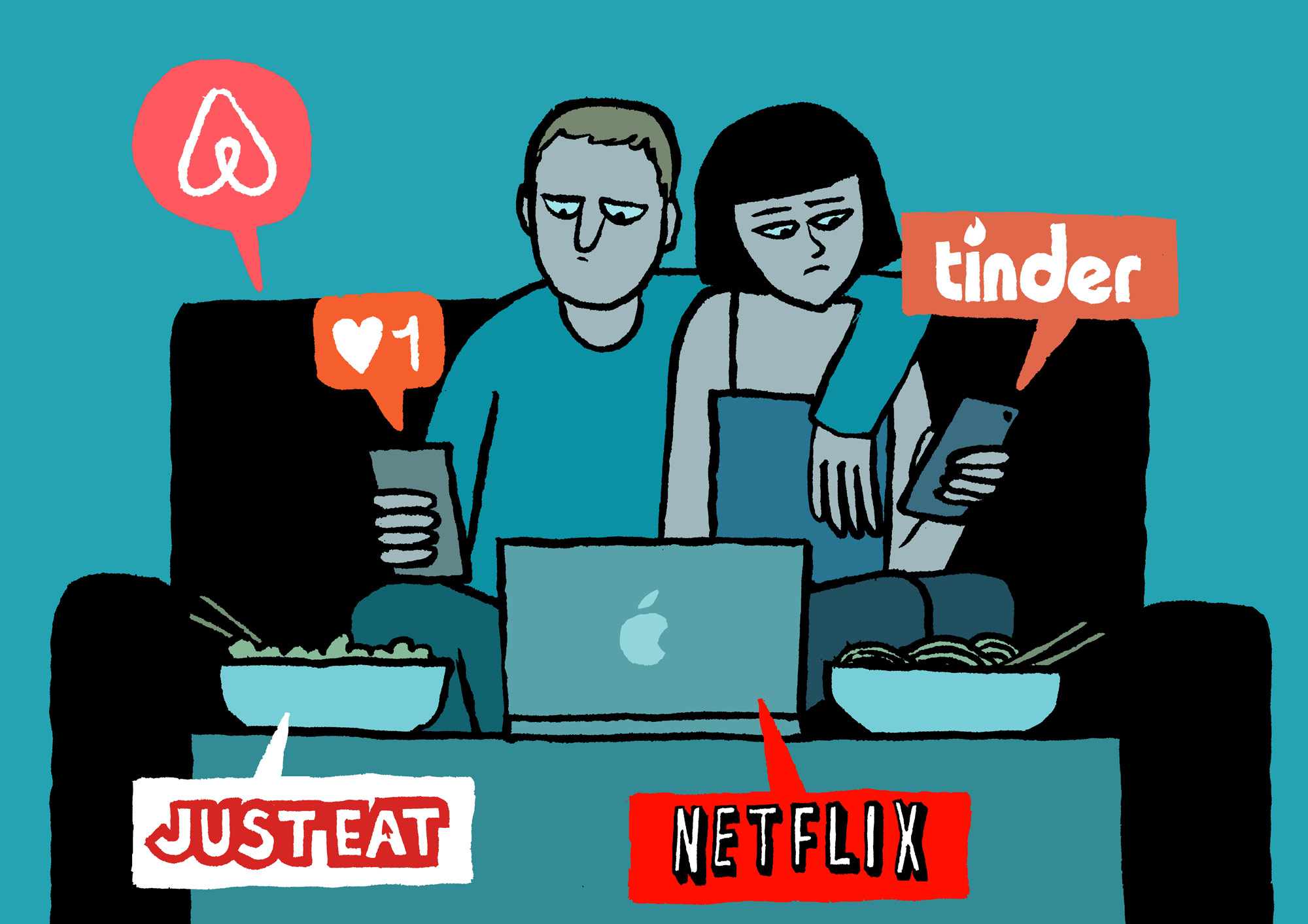

What advice would you give to a young person just starting out? If you want to make it in the long-run, you need to secure some sort of regular income. That’s the toughest part. There are big companies trying to make a lot of money, and illustrators always seem to be sort of expendable. Because of that, it’s definitely a good idea to have a handle on the financial aspects of your work without letting it dictate what you do. If you only do commercial work, then the extent of what you have to offer could become a bit limited. Using social media to produce and share your work, at least in my case, has been key to a healthy stream of projects.

Have you ever felt pressure to change your style to make yourself more marketable? No, I don’t think so. That would be a mistake, because people appreciate someone being genuine. If you become too influenced by others or worried if people will accept your style, you might not seem confident, and I don’t think anyone wants to hire someone who isn’t confident in their own work. Of course, I was probably influenced by some of the designers I admired as I was starting to grow into my own work. But by practicing and experimenting a lot, my style mutated into something more personal over time.

Was there a point when you decided to take a big risk to move forward? Not really. I was lucky that my big transitions between school and college and running my own commercial practice were all very gradual. I had three years to learn how to run a commercial practice while I was still in school, so there was a certain sense of protection while I was starting out.

Would you consider yourself to be creatively satisfied? Sometimes. I cherish having a playful approach to my personal projects. It’s gratifying to have a little playground where I can make mistakes, fail, and experiment. That’s super important.

Have you ever found yourself feeling creatively stuck or hitting creative blocks? Yeah, definitely. When I feel like I’ve done too much of the same, I feel a certain itch to try something else. It happens sometimes when I go through a period of doing a lot of work about serious topics and current events. I find that it can stimulate a lot of overwhelming or difficult reactions from people; they get quite agitated, especially on social media. Usually when that happens, I try to counteract it by creating work about lighter topics. Eventually, after I focus on lighter topics for too long, I know it’s time to change it up again. It’s about self-regulation.

What have been some of your favorite collaborations? Working with my brother is always an essential collaboration, but there are a few projects I’ve worked on with other brands that I’ve really enjoyed. One of my favorites is with the French clothing brand, Olow, with whom I have a really good relationship. I’ve always been extremely trusting and permissive with them, and they encourage me to do work that comes more from the experimental side of my practice, which I believe makes it more successful and genuine.

Has there been a time where you were presented with a project that really intimidated you? Yes. About four years ago, I was hired to work on a bar in France. It was a pretty humongous task, and it definitely wore on my confidence. The client presented me with their huge space, keys in hand, and said, “It needs to be 50 percent art space and 50 percent public space, and you can do whatever you want.” It was as daunting as it was exciting. Thankfully, they teamed me up with a lot of engineers, architects, product designers, and makers of all sorts who helped turn my naive ideas into something tangible.

Is there anything you’re excited to work on in the next few years that you haven’t already? I’m quite excited about teaming up with people who have good technical knowledge of different crafts I’ve never experimenting with. I’m doing sculptural exhibitions in Belgium, putting together a lot of capsule collections in Asia next year, and doing a show in San Francisco as well. It’s a nice and busy schedule.

I would like to experiment with sculpture more, and my brother and I would like to push ourselves to work with filmmakers or fashion designers in the future. There’s an animated series I’m doing with my brother that we’re both very excited about.

“I cherish having a playful approach to my personal projects. It’s gratifying to have a little playground where I can make mistakes, fail, and experiment. That’s super important.”

I want to take a minute to say congratulations, because I heard you recently became a dad. I did, yeah! Thank you very much. I am very stoked about that.

With all of your upcoming projects, have you been thinking about how becoming a parent will influence your creative and commercial practice? I finally hired an assistant, which is doing wonders for my sanity. That’s a big change for me. She’s been good at helping me handle a lot of emails and making sure we coordinate calendars and things like that. It’s much more organization than I’ve been used to before.

Now that I’m a dad, I’d like to focus more on personal projects. I also want to spend less time on social media, which I find quite addictive, exciting, and engaging. I’ve also sustained a practice of creating a lot of work quickly and quite regularly over the past two or three years, but now I think it’d be exciting to try to focus on longer projects, like a graphic novel or an animated series. I will obviously still be doing commercial work, just maybe shifting my focus a bit. I’m saying that now, but I’m quite compulsive in my practice. I produce a lot on a daily basis, so it might be difficult to try to change that. But it’s a good challenge.

Do you set aside time to draw for fun every day, or are you often pretty busy with commercial projects? It’s important to me to draw consistently every day, especially when I have a lot of commercial work to do. I usually set aside an hour in the morning to create something new and playful just for myself, like creative gymnastics. It helps me jump into commercial projects more easily.

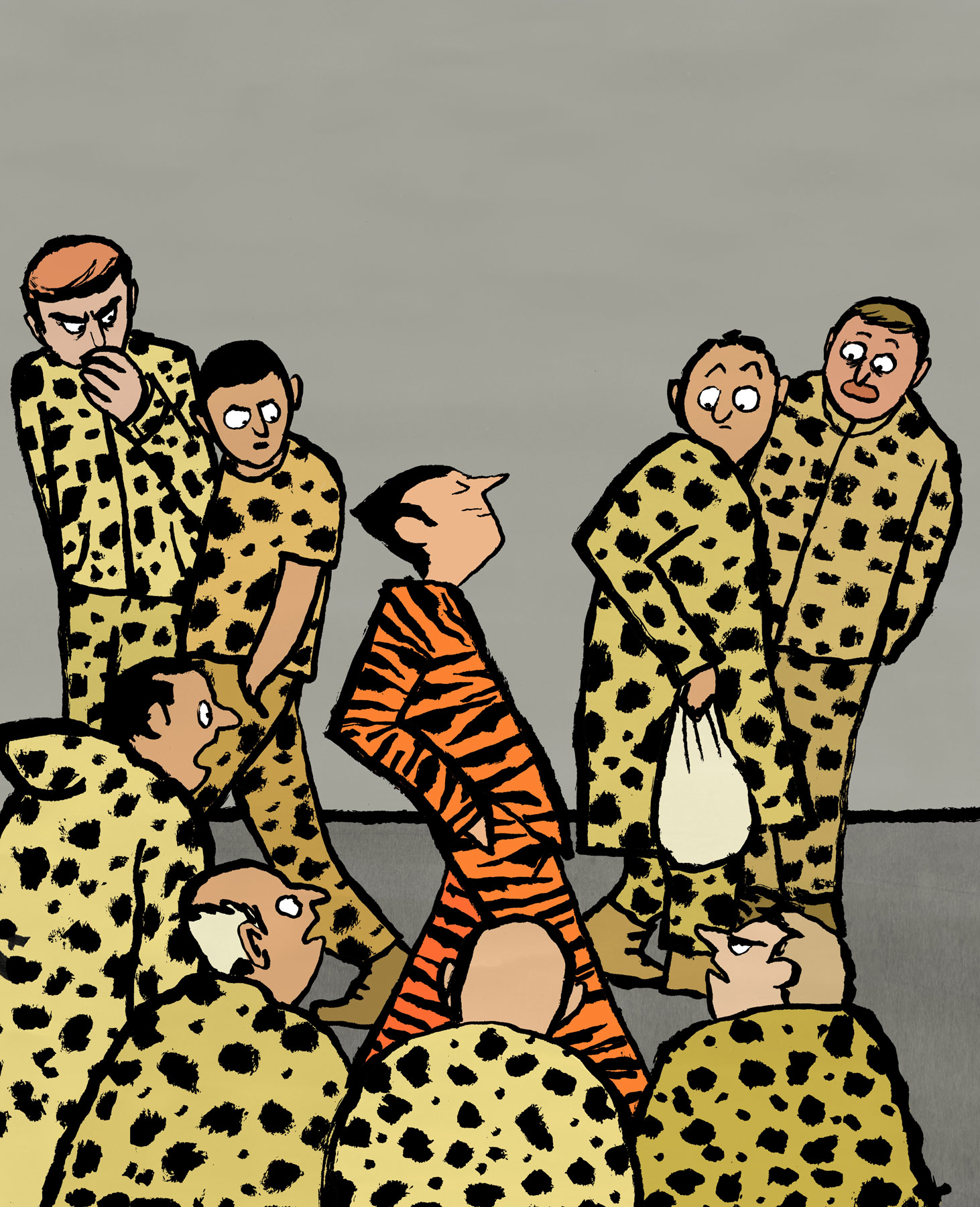

How does living in London influence your creativity or the work you do? London started everything for me. I moved here from a small town called Quimper that doesn’t have the diversity or influence London has. London is very exciting, because it is such a huge melting pot of people and cultures and languages from all over the world. When I first moved to London, I developed an exciting practice of doing drawings based on my observations of London’s culture. It was much like journalism, in a way, where I observed what was around me and tried to sum it up into visual article or stories. I recently did a solo show at Chemistry gallery called Allo?, which is based on social and antisocial behaviors I’ve observed. That body of work is definitely a product of my time in London.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people, whether online or in real life? Not too much, no. I share a studio with my best friend, who I met in Brittany, and we’ve always done our own things. He’s sort of my extended creative family. There are a lot of fantastic illustrators, artists, and designers who I get on with really well and keep in touch with, but I’m not sure that I’m part of a creative community. I’m quite focused on spending time with friends and family, and having a life outside of work, so community is important to me. It’s not like I made a decision to not be part of one, it’s just that it hasn’t really happened in the creative world so far.

It sounds like you believe in maintaining a healthy work-life balance. Yeah, I’m not keen on bringing commercial work home. However, I’m always thinking about my creative practice, so I take that enthusiasm home with me for personal projects.

Do you have any favorite books that have been particularly inspiring or encouraging to you? When I was studying in France, I discovered a book called House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. It’s a huge, fantastic book, and I became quite fond of it. House of Leaves is kind of a postmodernist, typographic take on a haunted house. It’s a bit meta and somewhat difficult to read, because the typography changes as the story progresses, but I found that to be such a clever use of the format. It has a great sense of playfulness, and it definitely influenced the sense of playfulness in my own work from early on.

What type of legacy do you hope to leave? I don’t know. I think the people will decide. I’d like my work to leave a playful and humorous reflection of the times that we live in; I think it presents a slightly distorted retelling of reality.

Now that you’re a parent, do you think of your legacy in those terms? Yes, but it’s very fresh, so it hasn’t quite formed into what I might like it to be yet. My 20s and 30s have been made up of an extremely fast-paced lifestyle based on constantly creating in an individualistic way. I think having to care about someone else is going to change that. I don’t know what that change is going to look like, but that’s the fun of it: not knowing.