- Interview by Tammi Heneveld September 22, 2015

- Photo by Christopher Parsons

Jessica Lehrman

- photographer

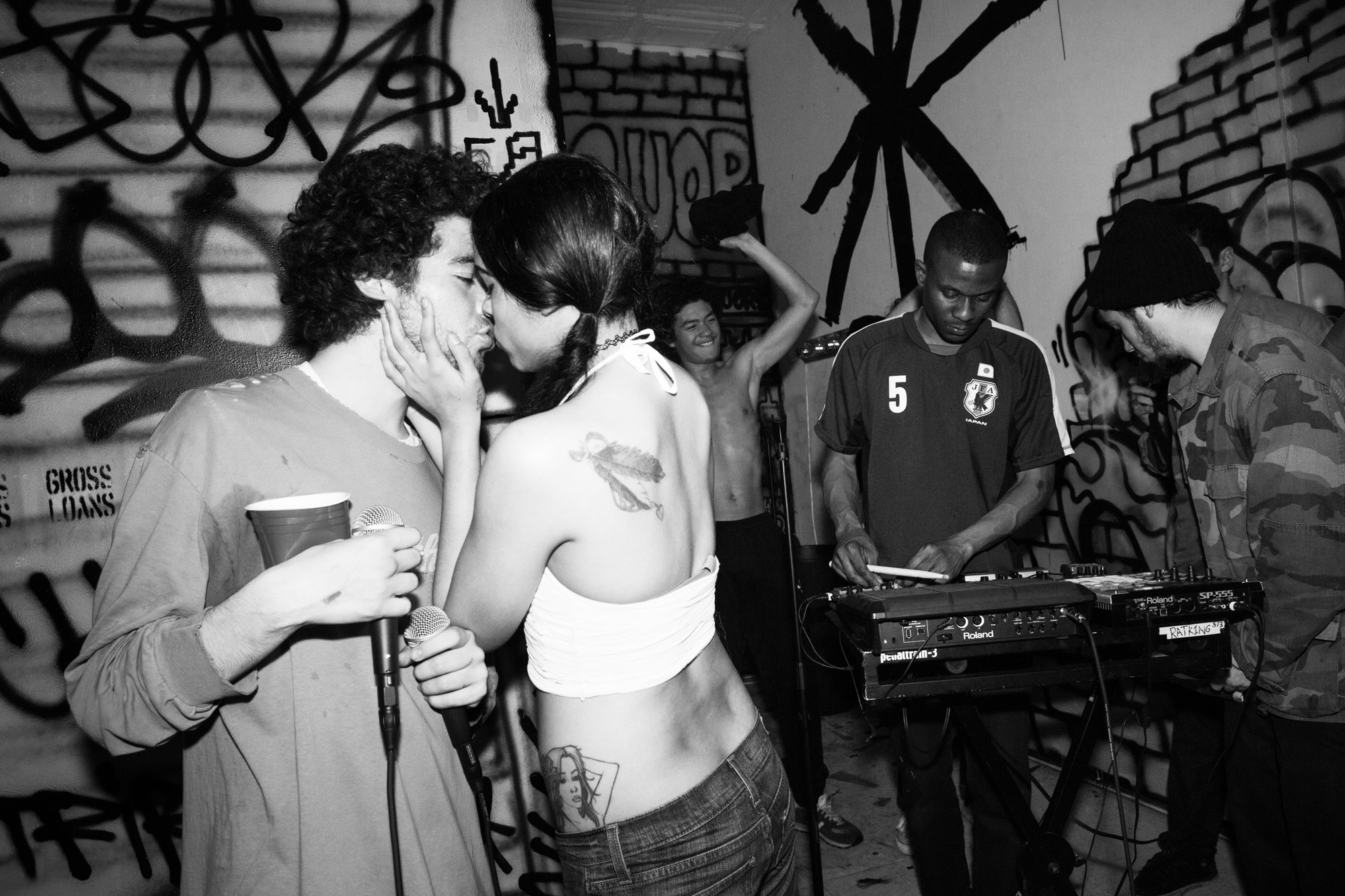

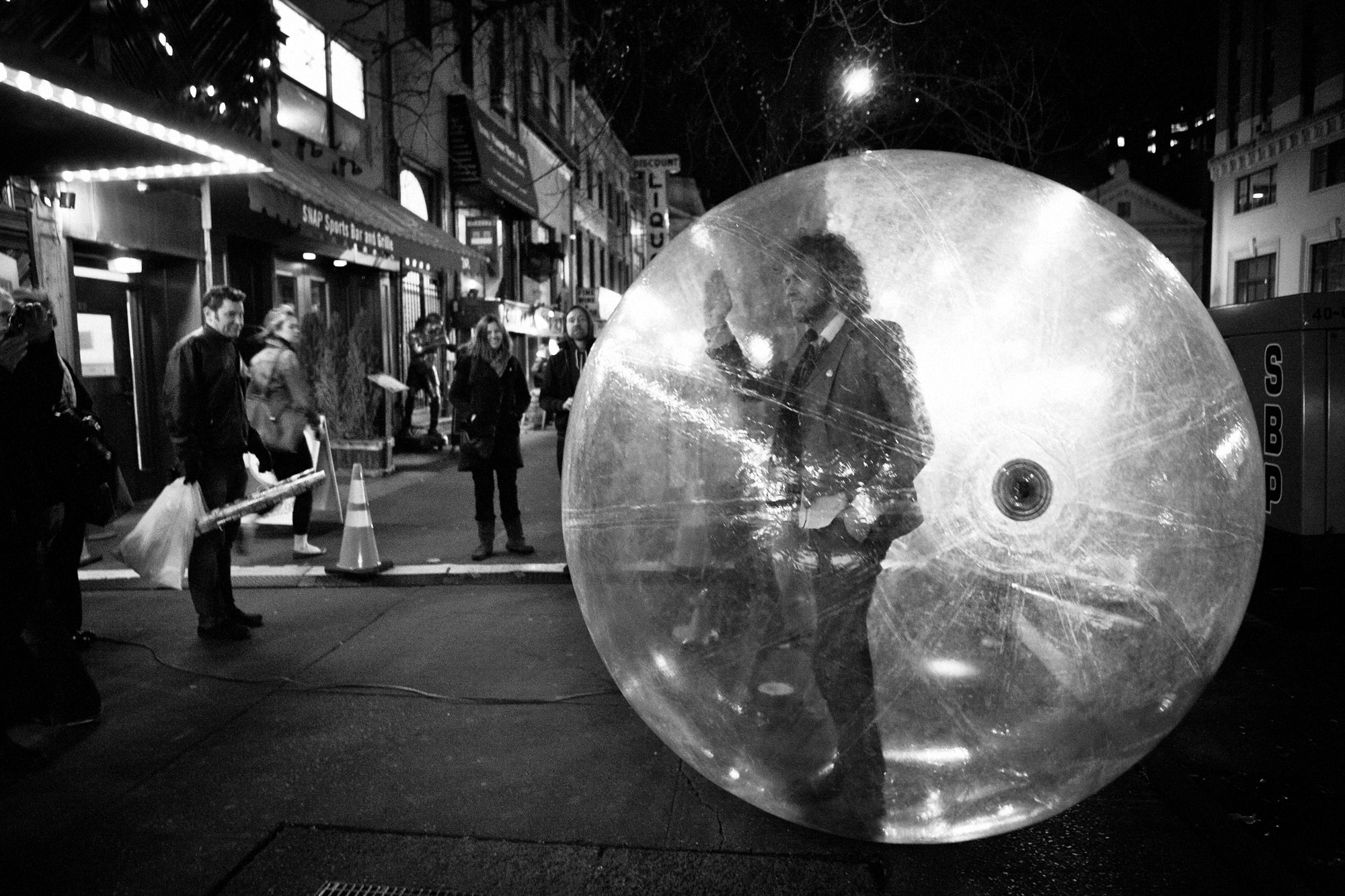

Jessica Lehrman is a New York-based documentary photographer whose work has been featured in publications like the New York Times, Rolling Stone, Vice, Vanity Fair, and Spin. Her voyeuristic, candid style of storytelling is pervasive across her work, whether she’s exploring New York City’s underground hip-hop scene, documenting a six-week road trip with her family, examining the Occupy Wall Street movement, touring fracking sites with Yoko Ono, or collaborating with fashion designer John Varvatos.

Describe your path to becoming a photographer. I fell into photography by accident. I originally wanted to be a painter, but I was horrible at it. The problem was that my parents are so supportive that anytime I did something, they’d say, “That’s so amazing! You’re so talented! You should do that for a living!” (laughing)

My dream was to go to Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), so I applied for their pre-college program. Since I didn’t go to high school, I needed to get some experience with that type of structure. The RISD program was basically a three-month introduction to college, so it was perfect.

Were you homeschooled? Kind of. I did a super alternative state-funded homeschooling program. We were required to study regular subjects like math and science, but we also took classes about sacred geometry and read books like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. If I ever have kids, they’re definitely going to do it.

When I was 16, I accidentally got hired to do a commercial for Cingular Wireless and made a shit-ton of money. I did not grow up with money, and it was the perfect amount of money I needed to attend RISD. I applied at the last minute, so I didn’t get into the painting program. Instead, I ended up majoring in traditional photography. I borrowed my friend’s Canon AE–1 without knowing how to use it at all. After shooting my first roll of film, I was completely hooked. I thought, “I’m done with everything else—I’m going to do this forever.” Looking back, I’m so glad painting didn’t work out.

Did you choose photography because you didn’t get into painting? Kind of. I wanted to get into the art world, and the photography program seemed like the most obvious way to see what it was all about.

After studying photography for three months, I learned that I hated art school and didn’t want to be there. I wanted to study business instead and become a professional photographer. I fell in love with photography because I love telling stories, and I wanted to tell stories without necessarily being an artist. I’m more interested in the journalistic aspect of photography. I knew that I would learn a lot in art school, but I’d also spend a lot of money that I didn’t have. I wanted to do nonprofit work and collaborate with artists and make money and help people instead of only helping myself. Don’t get me wrong: art school is amazing for lots of people, but it didn’t feel right for me.

After I left RISD, I took two years off. I lived in Central America and photographed there for a while before moving to Santa Monica, California. I ended up getting hired as a photographer for the Santa Monica Mirror after I met the art director, Deborah Daly, at a yard sale. It was so random. That woman changed my life. I love her.

Around 2008, some friends of mine were attending Purchase College, State University of New York. They told me to look into enrolling, saying it was like the cheap version of RISD. I didn’t necessarily want to study art, but I still wanted to be around artists, so I decided to apply. Unfortunately, they denied my application because I didn’t have a transcript. The closest thing I have to a transcript is a list of all of the feelings I had about my classes. (laughing) That didn’t work for Purchase, so I had to call them numerous times to convince them to let me in.

When I went to Purchase, I triple-majored in new media, arts management, and media, society, and the arts. It sounds more artsy than it was: most of what I learned was about marketing, how to run a nonprofit, and how to set up a business in the arts. It was amazing. I learned so much from it. I was able to work for the college doing photography and marketing, although I didn’t make much money. It also set me up to enter the music world, because Purchase was super music-focused, so there were a lot of musicians and bands that I could photograph.

I went there for two years before dropping out. During the summer of my freshman year, I went to India with a friend. When I came back to school, everything was different. I thought, “I can’t do this.” During my next year there, I slowly started feeling disenchanted by the idea of college. Then I got arrested, which was super expensive, and that basically served as the push to drop out.

After that, I moved to Brooklyn, and I’ve lived here for six years. It’s crazy! I feel so old. It’s the longest I’ve lived anywhere in my life. Growing up, my family traveled around a lot. My parents are gypsies, and we moved every three or four years. We lived in an RV a lot of the time. I call Colorado my home because I had most of my formative experiences there, but we only lived there for four or five years. So living in Brooklyn for six years is a long time for me. I’m starting to feel antsy.

“I borrowed my friend’s Canon AE–1 without knowing how to use it at…After shooting my first roll of film, I was completely hooked.”

When you first moved to Brooklyn, did you immediately start working as a photographer or did you have a day job? No, I was crazy. I made the stupid decision to not get a day job because I believed it would deter me from looking for photo jobs. It was the worst summer of my entire life. I was paying $400 a month to live in a closet in Bushwick with bed bugs. I was on food stamps, and I remember crying all the time because I couldn’t count up enough change for the subway. I was completely miserable.

It was good, in a way, because that’s how you get hungry. I was losing weight and thought, “I need to work.” But I told myself that no matter what I did, it had to be photo-related. One of my first jobs was working as a club photographer. I went out in the middle of the night with all of my camera equipment and shot super sketchy places on the Upper West Side, then came home on the day train with a handful of cash—it was bad. I also worked as a bar mitzvah and wedding photographer before working for a photo booth company. The photo booth job was actually the best, and it taught me a lot. It was all about getting people to pose within a very short amount of time. I shot hundreds of people who all wanted to take photos with their friends at events, and it was a lot of fun.

I did a lot of silly photo jobs for a long time, and I was poor for a long time. I’m still pretty poor, but at least now I’m at a point in my career where I’m actually turning work down, which is great. I don’t want to put my energy toward projects that aren’t positive or won’t move me in the right direction. I’m being more selective with what I shoot and how I shoot it and who I want to be associated with. But back then, I took whatever jobs I could.

Was creativity part of your childhood? Very much so. We didn’t have a lot, but my parents were able to create a whimsical, magical world for us where anything was possible. We traveled with the circus and met incredible people and had artists stay with us. I remember waking up in our one-bedroom apartment in Tucson and seeing 26 clowns sleeping on our floor and having to step over all of them to get to the bathroom. (laughing) My parents taught me that anything is possible and that you can do whatever you want to do.

Was taking the photography class at RISD the “Aha!” moment when you realized that photography was what you wanted to pursue? There was a moment at RISD when I took a photo and was chased down by a bunch of dudes because of it. That was the moment I realized how much power there is in photography. The adrenaline of being chased by those guys because I did something that meant something to them was a crazy “Aha!” moment of recognizing that you can make a difference and influence people with this medium. You can tell someone’s real or false story, and there’s a lot of responsibility in that. That’s exciting.

“I would tell my younger self not to compare my path to other people. It only inhibits your creativity and individuality…”

Have you had any mentors along the way? So many. I’ve had a lot of incredible people help me get to where I am now. Without them, I would be nowhere.

Jeffrey Henson-Scales, my current photo editor at the New York Times, is a big mentor. He is the one who pitched the piece I did on my family last summer, A Family Hits the Road. I was kind of against it at first because I hadn’t ever photographed my family before and didn’t want to put them on the spot where they would be judged by the entire world. But Jeffrey pushed for it and convinced me to try. He is also the one who hired me to do my first piece, Hip-Hop’s New New York. He has been a huge influence. Working with an editor at that level, who is so on it and experienced and yet still so humble, has completely changed my life and career path.

The man who introduced me to Jeffrey is another mentor. His name is Ashley Gilbertson, and he’s a war photographer for VII. He is my idol. Having someone bring you into the Times is hard, and Ashley totally went out on a limb to do that for me.

Deborah Daly, the woman I met at a yard sale in Santa Monica who hired me to work for her at the Santa Monica Mirror has had a big influence on me. That was one of those super cosmic moments that you can’t come up with an explanation for. She is an incredible art director and has experience laying out books, so she helped me understand how to edit my work and develop more focus and direction with what I shot.

There are a hell of a lot of people who have come into my life and given me moral direction. I’m flighty and get excited about everything, so I need people to tell me, “Jess, get grounded. You’re not going to Africa—maybe in a year. Right now you need to work on this.” (laughing) I constantly think, “Oh my god, I need to do everything or my life is over!” I’m very dramatic. Photography doesn’t help with my stress: I’m afraid I’ll die of a heart attack.

“When I am stuck in New York for too long, I start to feel convinced that it’s the entire world and all the petty shit here matters. But when I travel, I’m reminded of how little we all are and how much is out in the world.”

Was there a point when you decided to take a big risk to move forward? Going to college was a big risk because my parents weren’t supportive of it. My parents went to college briefly, so it’s not like they were unsupportive of me getting an education; they just didn’t think it was necessary. I had to take a stand and tell them that it was important that I do it.

Moving to New York was another risk. Leaving college was scary because it meant the end of an era. College had been my life, and I was heavily involved with that community of people. It was risky to come to New York, especially without any money—which is super stupid, and I hope no one else does that. But it felt right. Lots of my experiences that have felt scary or intimidating at the time have turned out well in the end, so I keep doing it.

I have chosen to shoot stories that have a darkness to them, and that darkness has definitely taken a toll on me numerous times. My family has been supportive of me through all of it, even when they probably should have said, “If you’re unhappy, you need to come home.”

Was it difficult to photograph subjects like Occupy Wall Street and fracking sites? Yes, but out of everything, the most darkness I have found has been in music. It’s difficult to witness the way people treat each other and how the industry works. There’s a lot of pettiness, backstabbing, and competitiveness; it’s a fickle world. I’m overly sensitive and I take what people say seriously, so sometimes it’s hard when I feel a certain way about something and the rest of the world doesn’t. For instance, I consider everyone I photograph to be a friend of mine, so I feel hurt if a band asks another photographer to tour with them.

Letting myself become so involved in that world brought me to a pretty depressed state this last year. I’ve been pulling myself out of it slowly by doing documentary pieces on cultures outside of music. I first got into music because it felt revolutionary, and I believe it still is. But I’ve seen musicians come in with grand ideas about how they’re going to change the world and say everything they want to say, only to have companies and media and fame dilute all of it. It’s disappointing to feel so excited about a revolution, only to have it end so quickly. I don’t know what I’m going to shoot next, but I hope I can find a real revolution somewhere.

That being said, Kendrick Lamar is someone who gives me hope, because he’s doing his thing and saying what he wants to say and not listening to other people. The underground artists I work with in Brooklyn are doing that, too, which is why I will work with them for the rest of my life.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself? Contributing to something bigger than myself is the only reason I want to do photography. I’m interested in people who are doing something to better the world. Photography allows you to be the light that shines onto someone so that the rest of the world can see them.

When you become a photographer, it’s easy to get caught up in thinking you need to photograph certain people and be a part of certain scenes. A couple years ago, that’s what I thought I needed to do. Now, I’m realizing that all I want to do is photograph people who inspire me and help them inspire others in return. I’ve pitched most of the underground artists I’ve worked with to every major outlet that I shoot for. I’m not saying they wouldn’t be able to if it wasn’t for me, but they’re now in the New York Times or Rolling Stone. The fact that I can give them that extra little push is the reason I do what I do.

Would you say that you’re creatively satisfied? No. I’m super depressed and I feel creatively stunted. I’m at a weird point in my career where I need to take a leap, but I haven’t figured out where I’m supposed to leap to yet. I feel very uncreative at this point in my life.

I probably shouldn’t be saying this shit. (laughing) I should probably be saying, “I feel great, and my work is awesome!”

Actually, a lot of people we interview say they’re not creatively satisfied. Really? Good. I feel like I’m at a place now where I’m shooting for the people I’ve always wanted to shoot for, but doing so doesn’t meet the same definition of success for me as it used to. When I was young and hungry, it was much easier for me to go out and shoot everything. I’m not that inspired by most of what I used to photograph anymore, but I don’t know what I want to photograph next. I’m waiting—which is not good—and trying to be proactive and searching for a story that I want to tell, but I haven’t found it yet.

I’m kind of disenchanted with New York right now, and I don’t know if I want to live here anymore. I want to find a movement or a group of people who are doing more for the betterment of humanity than what I’m finding in New York. Everyone here is struggling, and it’s hard to be creative when you’re struggling because you’re so focused on trying to survive. That means I’ll take jobs because I have to pay my rent. Maybe the right move is to live in a fucking cabin somewhere or live on the road: that way you don’t have high overhead and can shoot the projects you want. Maybe if I lived like that, I’d be able to say, “Yo, I’m so inspired right now!” (laughing) Maybe I’ve just lived here too long to remember that there’s cool shit happening around me, but the freedom of living on the road is so enticing.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out in photography? I would tell them to shoot as much as possible. You should be shooting everything when you’re first starting out because you don’t necessarily know what you’re interested in, so it’s great to get a little taste of everything. But after a while, it’s good to pick a single story and focus on documenting it so well that you become part of it. Through being a part of that story or culture, it’s easier for people to understand your work and hire you. That may not work for everybody, but the young photographers I see advancing the most are the ones who have direction and focus within their work.

The other advice is to share everything online. If you’re too nervous to show what you’re working on, you’re not going to gain an audience. If I were to start again, I might pick another direction and focus, but sticking with something and going full force in it is how I was able to land the projects I’m doing today. A lot of people are scared that they’ll be pigeonholed, but you can get out of that by changing your mind and moving on to something else that you’re interested in.

Is there anything you would tell your younger self to do differently?? Don’t shoot in JPG. All of the photos I shot in college are JPG, and they’re deteriorating. And I edited in JPG, so there are weird cross-process filters on them that I can’t ever remove because it’s part of the file. Shooting RAW is a must.

I would also tell myself to start a great backup system the second I start photographing. Right now I have a million hard drives that are all different, but there’s no system to them. I’m a fucking crazy artist, so I give my folders labels like, “That Day I Met That Cute Boy.” If I had started with a good organization structure from day one, I would be so happy. I’d also tell myself to backup everything. I have lost a lot of work from doing that. Oh, and buy insurance—I was robbed once and lost $15,000 of equipment.

Aside from practical advice, it’s also important to be nice to everyone. I don’t think I was ever mean, but there was a lot of cattiness in the industry, especially between female photographers. There is this weird mentality where women feel like there’s only space for one of us, so everybody else has to get out. But there’s enough space for all of us, and if we band together, we can kick all of the boys out! (laughing)

I would tell my younger self not to compare my path to other people. It only inhibits your creativity and individuality, which is vital for creatives. I would tell myself not to be so affected by competitiveness and to do what I need to do. There’s enough for everyone in the universe. Everyone is going to do their thing, and we’re all going to turn out great. I used to feel affected by looking at other people’s career trajectories, but now I think, “Eh, who gives a shit?”

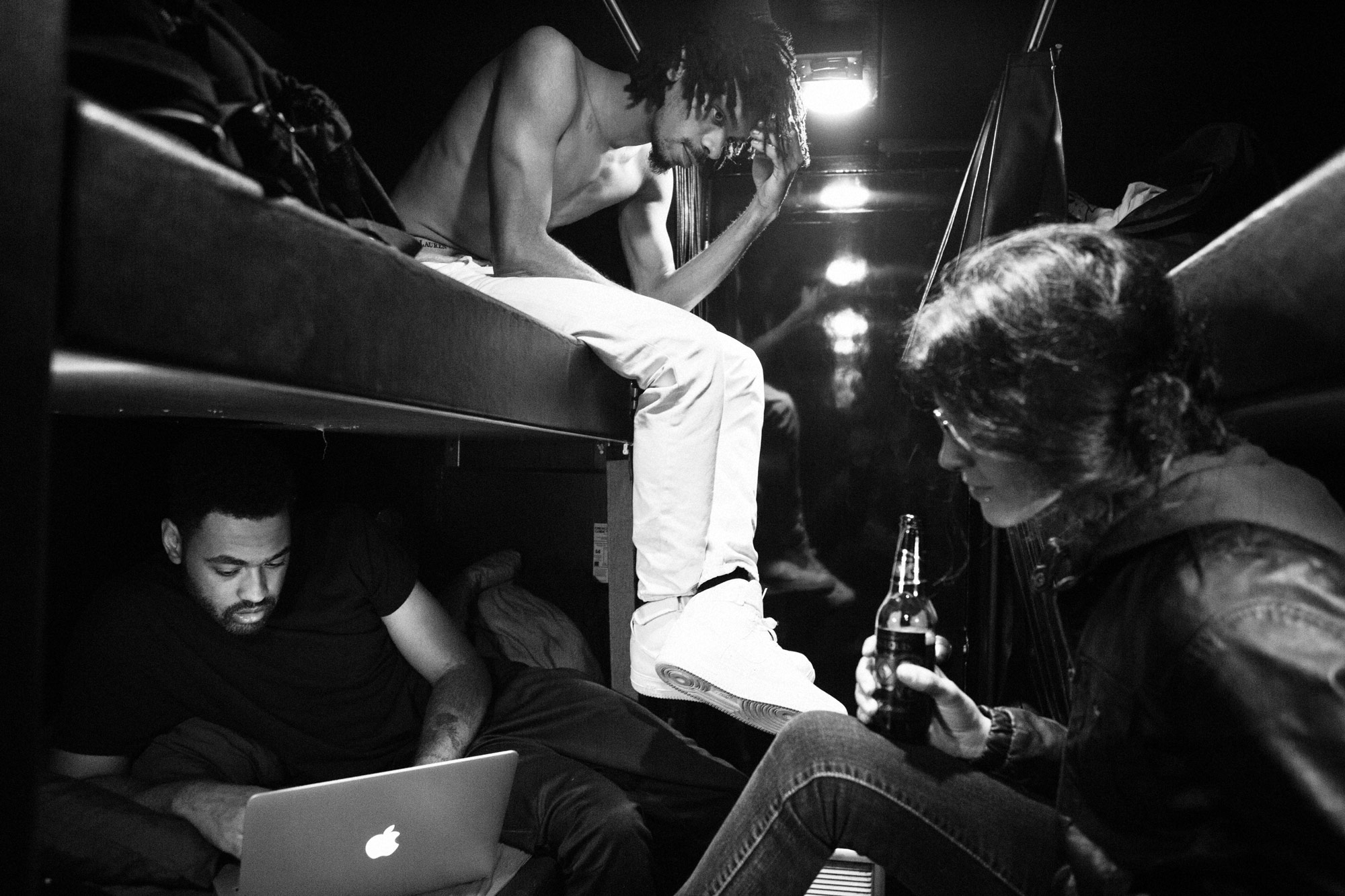

You mentioned feeling restless living in New York and wanting to travel. How does where you live influence your creativity? Traveling tends to kick-start my creativity. I grew up moving constantly, so it’s difficult for me to stay inspired in one place. When I am stuck in New York for too long, I start to feel convinced that it’s the entire world and all the petty shit here matters. But when I travel, I’m reminded of how little we all are and how much is out in the world. I find more magic when I’m on the road. I’m probably the happiest when I’m touring with artists. Going on tour is like having a slumber party with all of your best friends on a bus. It’s awesome! I don’t know if the rappers would see it that way, but that’s how it feels to me.

Visiting my family also inspires me a lot. My parents just moved back to my small hometown in Colorado after living on the road for the past three or four years. I’ve gone to stay with them four times this summer, and I feel so much more inspired to come back to New York afterwards.

Travel is my ideal way of life, and I wish I had the money to do it more often. I’ve found that I shoot more when I’m traveling. The last time I went to Colorado, I discovered the rodeo and bull riding and became obsessed with shooting that. I love weird, old Americana culture. I haven’t experienced much American culture in my life, so when I see it, I find it fascinating. The display of masculinity in middle America is so interesting because it’s so different from everything that I’m used to; it’s similar to the display of masculinity I’ve found in rap. It’s two sides of the same coin.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community? Very important. Well, it’s important to me to be part of a family. I grew up with a family that was so embedded in their community that I feel like I need to make little families everywhere I go. Whoever I shoot becomes part of my family, and whatever culture or society I end up in, I try to find my brothers and sisters within it.

I don’t need a super-active social life, though. I’m a loner in the sense that I don’t need people around me. I don’t feel like I’m a social person, although everyone who knows me would probably disagree.

What does a typical day look like for you, whether you’re traveling or out shooting or in the darkroom? I wish I was in the darkroom. I actually don’t shoot film anymore; it’s all digital now. I would love to shoot more film, but it’s so expensive and impractical, especially when I’m doing photojournalistic projects with super fast turnarounds.

My day usually consists of photographing at least once, editing on my computer, and drinking lots of coffee—I meet with tons of people, so I’ll set up coffee meetings and be extremely caffeinated all day. Lately, I’ve been doing more assignments than pitching, which is cool. It can be tiring to be constantly pitching and coming up with ideas, so it’s fun to be given something new that I wouldn’t have thought of. I’m so in my head that it’s nice to experiment with subject matter that is outside of what I normally do. I have no idea what I’m going to end up doing when I am given an assignment: it could be going to a baseball game in Philadelphia to photograph 13-year-old baseball players, or a rap show, or someone’s mom’s house in Flatbush.

There are a lot of things I want to start working into my day. I’m trying to do yoga, but I don’t; I’m trying to eat healthy, but I don’t. (laughing) I am trying to be better about talking to people. People get mad at me because I don’t reach out to them, especially my family. I’m trying to be a better friend and family member and stay in contact with people.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave? No matter what I’m shooting, my main focus is to help people’s stories be heard. I want to shine a light on people who otherwise wouldn’t be visible. Saying that I want to change the world may sound too lofty, but I’m interested in using my work to expose and promote incredible people who can inspire others to be revolutionary and create positive change in the world.

“…I’m interested in using my work to expose and promote incredible people who can inspire others to be revolutionary and create positive change in the world.”