- Interview by Tina Essmaker September 23, 2014

- Photo by Collin Hughes

Kevin Allison

- comedian

- entrepreneur

- writer

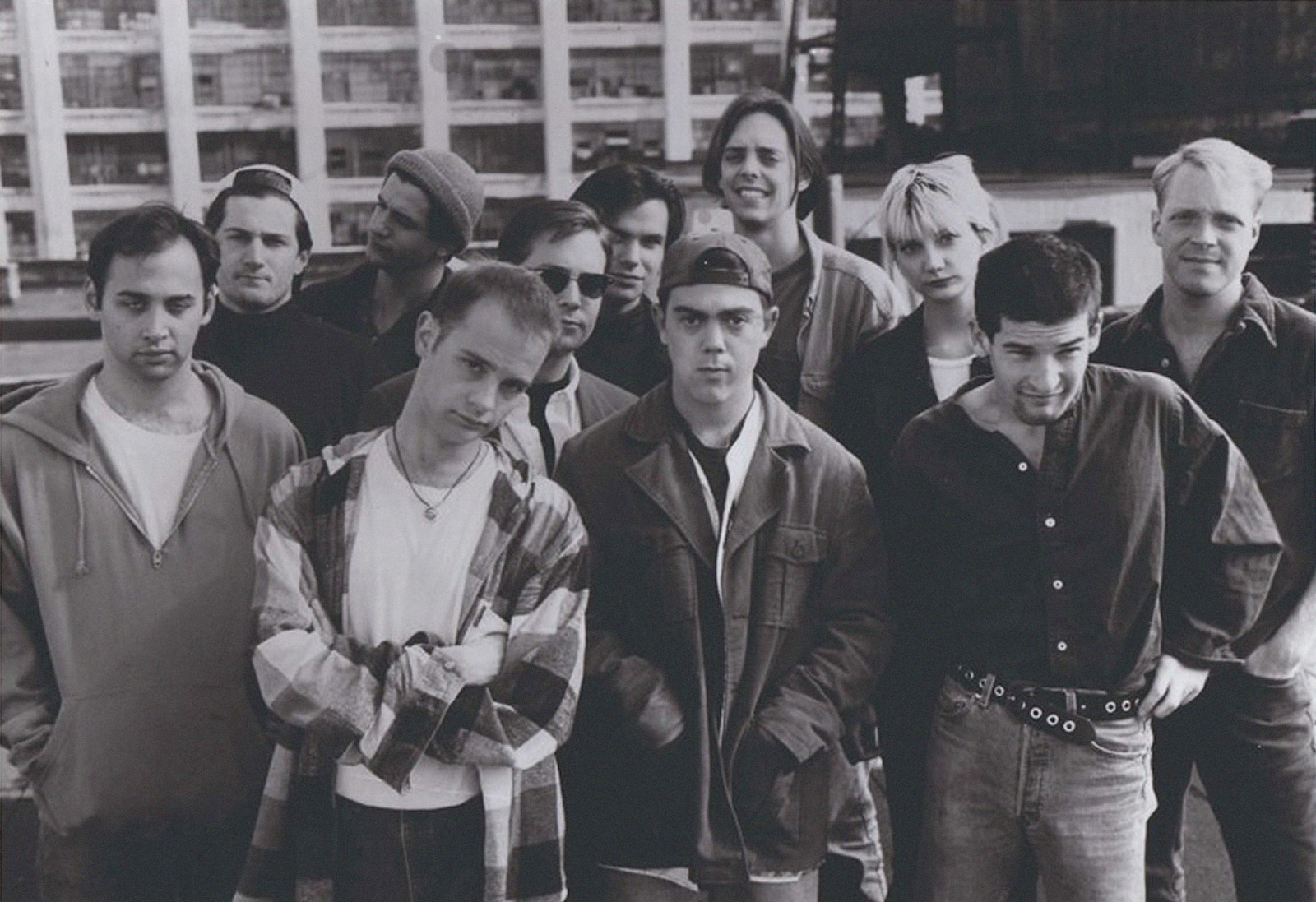

Kevin Allison is a New York City-based comedian and founder of RISK!, the live show and podcast. He was previously part of the legendary sketch comedy group, The State. Kevin has served as the Artistic Director of The Peoples Improv Theater in New York, taught comedy writing at New York University, and founded his own storytelling school and corporate training center, The Story Studio.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Two, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Two, available in our online shop.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

If I wanted to talk about the true origins of why I’m doing what I’m doing today, I’d say it’s because I knew I was gay when I was a tiny, tiny kid: it was one of the first things I was conscious of.

Mike Daisey, a big storyteller in our community, has said that it’s difficult for someone to have been a smart, self-aware kid because what happens to a lot of smart, self-aware kids is that everyone else catches up later on. The kid grows up thinking, “Oh, I’m a genius: I understand myself so much better than everyone else, so I’m going to be the smartest person in the world.” No. By the time you’re graduating from college, everyone else has already figured out that they’re gay or straight or whatever, and you’re just the person who is a little bit scarred because you spent too much time believing that you were special, or an alien from outer space, when you were a kid.

I grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, which is super conservative. Cincinnati had an obsession with sex back in the day: no sex, no sex, no sex. For example, the Mapplethorpe trial and Larry Flynt scandal happened there, and when the play Equus came to town in the early 1970s, the police raided it because a kid was naked on stage for a while. (laughing) As a young boy, I was incredibly aware that I liked boys, but also that it was horribly wrong in the world’s eyes. It was evil and defective and lame, and I had a lot of fear and defensiveness about it. My mother was one of those typical puritanical Cincinnati mothers who, when the song “Sexual Healing” came on the radio, turned it off and told my sister and I, “When that song comes on the radio, the radio goes off.” (laughing) So I thought, “Oh god, I have to keep this in!” I knew I couldn’t come out of the closet as a child because people would say, “You’re just a child, what do you know?” So I became funny. It was a way of letting people know that I was weird, but that it was okay because I was friendly.

What I learned from my being funny was that people aren’t usually prepared for weirdness, so you have to spring it on them in little surprises. (laughing) So I would be an extremely good boy throughout most of the day, and then when I felt like I was with a group of people who made me feel like it was okay, I would do something strange and silly. For instance, in high school I pulled crazy pranks and ran around naked at parties.

In high school, I also became one of the stars of my school’s musical theater program. When the decision of trying to become either an actor or a director came up, I decided to go to film school at New York University (NYU) to become a director. I left Cincinnati to attend NYU, but I quit the program almost immediately. There was so much machismo shit in the program, and the girls there—at least in 1988—faced outright, blatant sexism from the teachers right in the middle of class! Within the first week of school, a girl brought in a project that was different in some way, and the teacher said that she should “go home and keep working in the kitchen.”

Whoa! Did you drop out of the program?

No, I didn’t. I finished NYU, but I changed my focus from directing and cinematography to writing and acting.

By the time I was in my 20s, I was at that stage where it was okay to be gay. It was around that time that I became involved with the MTV sketch comedy show, The State. When I first met those guys, I was just another freshman at NYU: bland and normal and a good boy. But every now and then, I would do something crazy like take off all my clothes in the middle of a bar. After that, they put me in the group. But that’s not sustainable. After studying improv, I found out that it’s not about random bursts of craziness; it’s about committing to a story. I hadn’t learned that, even after being on television.

In The State, my cast members and I were a typical group of comedians in that we were used to ribbing and roasting each other in order to poke at each other’s egos. It’s something a lot of comedians do, but it can get a little out of control sometimes. Many comedians have a great deal of insecurity, and it’s usually about being different. At one point, I suggested that the group have a 30-minute check-in at the beginning of each day where we could say anything we wanted, and it didn’t have to be funny. In fact, the goal was not to be funny, but to be honest about how we were feeling.

During that check-in, people loved my stories the most because I was the one who didn’t hang out with the rest of the group at night. I was off having my gay adventures around New York City, and then I’d report back on the next day. One of my castmates, Michael Ian Black, used to tell me, “You should go up on stage and tell those stories to audiences.” I was terrified of that idea because I felt like it would be the ultimate coming out. I was obsessed with the idea of coming out, but also afraid of it. It’s almost like how kinky people have a fetish: they want to do something so much, but as soon as they do it, they might be loaded with shame. Because of that, a lot of people in kink will develop role-plays where someone will shame them after they do something kinky, but then give them aftercare by saying, “No, it’s actually okay.” I was afraid of telling my true stories on stage and having everyone say, “Oh my god! Who is this crazy pervert?” (laughing)

When The State broke up in 1995, I was scared. When you’re a part of a group like that, you have people to take care of you if anything goes wrong. We would walk into a room to meet with an executive, and the executive would say, “Oh, there’s 11 of them.” (laughing) I just watched a documentary about Dave Chappelle and Neal Brennan called Chappelle’s Show: The 50 Million Dollar Question. It’s about how executives would get Neal in a corner and say, “Well Dave said you don’t agree with this,” and then they’d get Dave in a corner and tell him, “Well Neal said you don’t feel that way.” After a little while, the two of them were paranoid about each other. But with The State, there were 11 of us, so we could all check in with each other and say, “No, no, no—we’re going to bulldoze these motherfuckers.”

We eventually quit MTV to go to CBS, but then we were fired from CBS after doing our first show for them, which was a Halloween special. The day we were fired, I went back to my little apartment on Ludlow Street, laid down on the floor, and began shaking. It felt like my body knew that something too powerful for me to digest was happening, and indeed it was. It was my worst fear: all of a sudden, I was alone, and I was now having to present myself to the world. I had been the “nice guy” amongst a group of people who had rather thick skins—I had typically been more of a people-pleaser. I felt a little bit beat up, and I was scared of comedians in general.

Soon after, I began doing character monologues on stage, similar to what Andy Kaufman or Whoopi Goldberg did. For inspiration, I looked to Whoopi Goldberg’s 1983 Broadway show, The Spook Show, which was made up of five characters. All five characters told stories: one is Jamaican, another is a little girl, another is a heroin addict. I wanted to do something like that, so I decided to go on stage and do crazy, kooky characters telling stories. I tried that for about 12 years.

That’s a very long time.

Well, that’s actually an exaggeration, because if I had been doing it every night, then something might have happened. But instead, I was doing it in bits and pieces: I would do a few performances, then get scared and not do another performance again for a few months. If I had taken improv classes right after The State broke up, I would have learned in a safe space: those classes offer a safe place to learn that it’s okay to fuck up. The stakes aren’t as high as being in a pitching meeting at MTV. If you say something and people don’t laugh, then no one cares—they’re just waiting for the next joke they might laugh at. I thought that I had to be perfect back then because I was around so much amazing talent when I was on The State.

Those 12 years were a real starving artist, belly-of-the-whale period. The fact is, I’m just one of those people who is creative and artistic, but very much a space cadet. There is something called Executive Function Disorder, or EFD. If you ask someone with EFD, “Do you want a peanut butter and jelly sandwich?” They’ll reply, “Yeah.” But if you ask them, “Do you want a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or a ham sandwich?” then they’re overwhelmed. (laughing) I’m that guy who has a hard time keeping the apartment in order, keeping the email in order, and just doing adult things. But I’m good at creating stories.

Finally, in 2009 I did a show called F*** Up, which was about five characters who had fucked up their lives and careers. That show was my idea of an autobiography: one character was a Jewish vaudeville performer from the 1920s who was jealous that his partners had gone on to become famous in Hollywood while he had struggled; another one was Frankenstein’s monster talking about trying to make things work, but people not seeming to understand him, and having everything become a colossal disaster. These were sides of my personality I was revealing on stage, but I didn’t feel as though I was quite connecting with the audience. When Michael Ian Black came to see the show in San Francisco, I asked him what he thought. He told me, “I think everyone wanted you to drop the act and start speaking from the heart as yourself. Tell your own stories.” It was the same thing he told me way back when we were on TV, but it just felt too risky. I’m such a pervert, such a Midwestern polite guy, such an absurdist, and so corny—I’m a mixture of things that don’t seem to make sense together, and Hollywood wouldn’t get it. When I told Michael that, he said, “Look, the key word you used was risky. If it feels risky, then you’re probably opening up a bit, which means that people will open up to you.”

A short while after that interaction with Michael, I decided to tell a story for a show called Stripped Stories at the Upright Citizen’s Brigade Theater in New York. I decided to be as risky as I could, so I told a story about the first time I attempted to prostitute myself. I was about 22, and it was a failure—I turned out to not be very good at that job, either. It was a good comedy of errors, though, so it made for a fun story, but I was terrified to tell it.

On the day of the show, I called Margot Leitman, who used to run Stripped Stories with Giulia Rozzi. I said, “I don’t think I can do it. I’m so scared. It’s too risky.” She said, “That’s great news!” She told me she’d had people who were used to getting up on stage six nights a week, but had freaked out about doing this show because it’s too personal. She told me, “If I can convince those people to do the show, I know that their story is going to be the one that hits it out of the park.” So I agreed, and something magical happened that night. When I told that story, I felt an enormous listening coming from the audience, an enormous opening-up. I noticed that I could look into people’s eyes more when I was speaking as myself as opposed to when I was speaking in character. There was relating happening.

After that night, I thought, “That’s it.” I took the subway home and started thinking of creating a show called RISK!, and the idea had wind in its sails from the beginning. As soon as I started telling other comedians, they said, “I want to do that show!” Everyone else I talked to—regular civilians—said, “I want to see that show!” And it took off. I was still dirt poor for the first few years, but I’m finally in a good place with it now.

Thankfully, I met two people who have helped me out a lot: JC and Jeff Barr. JC is my producer, and is basically like my dominatrix: she rides me with the whip, yelling, “Do this, do this, do this.” Jeff is my episode editor. He and I work together on a daily basis even though he lives in Colorado. We’ve never met face to face, but we still have a deep relationship because we’re talking to each other constantly.

Since we started RISK!, it’s been great to see it take off gradually. In the beginning, I kept thinking, “We’re going to hit that tipping point, that one week when this explodes!” That’s the narrative you’re so used to hearing.

“…I realized that not only could I begin pulling deeper stuff out of others, but it was time for me to begin pulling deeper stuff out of myself as the guy who was leading this whole venture.”

Yeah. You think, “Where’s the magic?”

Yeah. Instead, it’s seen an ever-so-gradual growth in popularity—very gradual. But that is the sign of a healthy business.

So you’re doing the RISK! podcast and live shows, but you’re also working on another project as well?

Yes, for about two and a half years I’ve been working with The Story Studio, which offers storytelling workshops in New York and LA, as well as online. That came about when I found myself getting so much joy out of helping people prepare their stories for RISK! shows that I began to realize that the principles of storytelling apply to anyone in almost any context. It’s been an endlessly fascinating experience. I’ve worked with preachers, and I’m supposed to do a class at Harvard Divinity School soon; I’ve helped people develop solo shows; I even worked with a therapist who wanted to use role-playing exercises to help his patients—we literally did the class in his office, where I analyzed his stories from a narrative perspective. Recently, I taught a workshop for a bunch of insurance salespeople. When I first heard that they did for a living, I thought, “How am I going to relate to these people?” But it was awesome! It was a two-day workshop, and I was giving everyone hugs at the end of it because we had some real breakthroughs talking about health insurance! (laughing)

I’ve watched a lot of comedy shows online, but most focus on culture or broader aspects of life that are more removed from the comedian’s personal experiences. But comedians talking about themselves is awesome! You can use comedy to help people open up about difficult experiences.

Oh, yeah. What happened early on in the history of RISK! was that I started inviting mostly comedians to come on the show and tell stories. When we started putting the show out to regular people, we began getting emails from fans. People would write to me, saying, “I have a story about how I was molested as a child, and I would like to share it,” or, “My sister overdosed on cocaine a year ago, and I would like to tell that story.” So I started sitting down with a lot of these folks, and I began asking our podcast listeners, “Do any of you want to share your stories? Let’s give it a shot.” And it was some of those stories that deepened the podcast more profoundly than ever before. We had stories that came from people who didn’t have writing or performing experience, but they understood what the podcast was about, and they jumped right in.

Here in America, we pride ourselves on being such a melting pot, but we are so segregated in so many ways. I’m not quite sure how to go about it, but my new goal is to start getting more stories from people who feel marginalized in society. There is a tendency of like circles to be attracted to like things, and RISK! tends to attract people who went to college and are at least doing okay. But I would like to spend more time hearing the stories of people who the country has not been there for in a supportive way. For example, I would love to do a show at Rikers Island, like what Johnny Cash did for Folsom Prison, but we would have prisoners get on stage and tell their stories. We have actually approached the prison about doing this, but there’s a little bit of trepidation about the idea. (laughing)

Was there an “Aha!” moment when you knew that comedy was what you wanted to pursue?

My “Aha!” moment was probably when I realized that comedy was something that worked for me. On my first day of kindergarten, I was terrified. I knew I was gay, and I had spent the prior year worrying that once I went to school, I would be in a social environment where other kids could observe me all day long; if someone figured out that I was gay, then I would be bullied and yadda yadda. At 8am on the first day of school, I stood in a single-file line with the other students waiting to go inside. All of a sudden, some kid pointed at me and said, “Why is your hair orange?” And then another kid said, “No, it’s red, like the head on the dick of a dog!”

What?!

Yeah. But when they started laughing at me, I thought, “This is awesome—they’re distracted by my red hair!” So when they gave me a hard time, it was just about my hair! (laughing and clapping)

Anyway, back to your question. When I was growing up, my father loved two things. The first was football, which I have never cared about. I have two older brothers, and he took them to games all the time. The second thing my father loved was opera. When I was about six or seven years old, he realized, “Okay, this is the son who I can take to the opera.” (laughing) I began listening to music like Free to Be… You and Me and the soundtrack from Jesus Christ Superstar, and I started watching variety shows like Donny & Marie. I remember being blown away by the operas and musicals, and that’s when I became interested in the idea of becoming a performing artist.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

In retrospect, I’d say that Spalding Gray and Mike Daisey and Julia Sweeney, who played Pat on SNL—those people and The Moth and This American Life did have an effect on me. I consider all of that a mentorship, but I never fell under anyone’s wing or studied under anyone.

I’d say that The State was my ultimate creative mentoring. It showed me that, if people are really, really determined to make things work, they can often find a way. To me, it was mind-boggling how I had all these psychological hangups; when I’d hand in a sketch at MTV and it would be rejected by the executives, I’d nurse that wound for days. Someone like Tom Lennon or Ben Garant would go back to the drawing board. There was an attitude of, “I’ll do whatever it takes,” and I was always a little too precious for that. In the years since I’ve learned that it’s okay to not be perfect all the time, and to just keep churning shit out.

“…you have to find a balance between perfectionism and not letting perfectionism get in the way of you actually putting stuff out there…Don’t beat yourself up too much for what’s not perfect; beat yourself up just enough to make the next thing better.”

This is something you talk about often. What is the biggest risk you’ve taken?

When I started the RISK! podcast, I was telling stories about sexual escapades I’d had in my early 20s, so there were already 15 or 20 years between me and those things. Then, early on in the show, I got divorced; I had been with a man for nine years, and part of the reason we had to get divorced was because I wasn’t bringing in any money. I had to make this new show work, and it had become a full-time job, but it wasn’t yet making any money. My ex told me he couldn’t wait for that to happen, so I had to start dealing with dating again. It’s funny because my experience was the opposite of Louis CK’s experience; when I got into my 40s and was dating again, I found this genre, this niche of gay men who are kind of bearish and have beards. People call them daddies, and a lot of young guys are way into it. I’m like, “I’ve finally hit my stride!” because when I was in my 20s, I was so uncomfortable with my own body, even though I was going after twinkie boys. That never changed for me, but now I’m this daddy kind of guy, and a lot of guys are attracted to me—and I didn’t even have to go to the gym. (laughing)

Anyway, there was one weekend when I was asked to do a show in Provincetown. I went there and met this beautiful, beautiful Vietnamese boy. We had this 24-hour romance, which was kind of like Madama Butterfly in the beginning, like I may be in love with you. The next day, he said something very cruel to me. I was so crushed and so embarrassed about my naivety. I didn’t have a therapist at the time, but I did have a recording booth. I recorded the story, known as “Kevin goes to P-town.” It was the very first time I told a story, not in front of a live audience, but in my recording booth, imagining I was talking directly to the RISK! audience, confessing my sins. I was raised very, very Catholic, and that’s how I was used to confessing my sins: in a little booth.

I published this episode, and it was very graphic. Being graphic about sex is one thing, but being graphic about the moments of intimacy between you and another person is really vulnerable—those moments of connection and disconnection while you’re having sex, the insecurities, the overwhelming emotions. When I pressed send, I was numb and shaking. Nothing we had done up until that point had ever gotten such a reaction: emails poured in, there were all sorts of comments on the website, people were responding on Twitter and Facebook. People said it was on another level, and they were so supportive. That was when I realized that not only could I begin pulling deeper stuff out of others, but it was time for me to begin pulling deeper stuff out of myself as the guy who was leading this whole venture. It’s been difficult since then because, honest to god, I don’t have as much time for little adventures. (laughing)

You mentioned earlier that your family was conservative when you were growing up. Are they supportive of what you do now?

To be rigorously accurate, my family is politically liberal; they’ve always been Democrats and have always had a problem with the Pope, except this current one. They’re on the right side of most things—it’s just sex that wigs them out. Well, I should say it’s my mom who’s wigged out by sex. I don’t want to be disrespectful in the way I say that either. I think a lot of my mom’s concern has to do with conformity. I first came out of the closet to her at 18, and a few days later when we were driving in the car, she said to me, “I have to ask you. Is this whole ‘I’m gay’ thing just another way you’re trying to be a nonconformist?” To her, conformity is of tremendous value. It’s a way to get by successfully; and I think that’s the case for so many people.

My parents are not Internet-savvy. They’re in their mid–70s and just don’t know computers. They don’t even really understand what a podcast is, but they do understand that I make a radio show that reaches people over the computer, and that it’s also about stories. They also know, because I’ve told them explicitly, that a lot of these stories are R-rated, or even X-rated, quite frankly. They know they don’t want to listen to the show, but they like the idea that I’m helping people express themselves.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Oh, gosh. Yeah. It sounds flaky to say because I don’t believe in astrology, but the description of what an Aquarius is—which is what I am—is spot on. I’m the person who has this dream of helping people have more connection and community and brotherhood and fellowship, the person who wants to lead the human family into being more human and more of a family. Ironically, Aquarius’s are also hard to get close to because they’re usually more focused on everyone else.

“This is the do-it-yourself era. Technology gives us the ability to put stuff out there on a regular basis, but getting up in front of people on a regular basis is also very important.”

Do you feel creatively satisfied?

It comes and goes in waves. When I feel most creatively satisfied is when I’ve worked on and presented a new story. Honestly, I actually enjoy writing the stories and putting them together more than performing them. I enjoy performing, but here’s a side of me that’s also introverted—I have this battle between introversion and extroversion.

Unfortunately, I have not written a new story in a long time because I’m now running a business; both RISK! and The Story Studio are crazily time-consuming. I do love helping others tell their stories, but I’m a little embarrassed that I haven’t come up with a new story in a while. To be totally honest, in the past year or so my kinkiness has gone into terrain that’s a little bit bizarre to the extent that I don’t know how I feel about it. (laughing)

You need to go on an adventure so you can write a new story.

I need to do another story where I really kind of grill myself and admit to my failings. In the time I’ve been making a living doing this and having a little more success being the “daddy” dude, I’ve made a lot of mistakes. Having this awakening being this kinky guy, there’s a lot of risk involved, whether it’s psychological or purely physical. There are a lot of little stories I haven’t told that maybe I should combine into one big story called “All the Things About Myself that I’m Worried About Right Now”?

You should! This is a good one: What advice would you give to a young person starting out?

This is the do-it-yourself era. Technology gives us the ability to put stuff out there on a regular basis, but getting up in front of people on a regular basis is also very important. I think you have to find a balance between perfectionism and not letting perfectionism get in the way of you actually putting stuff out there. That really stymied me for years and years. I recommend taking workshops and meeting people who are actually doing shows, making videos, and making podcasts. Try to stay as active as you can with creating stuff. Even if it’s not perfect, you will gradually get better and better. Don’t beat yourself up too much for what’s not perfect; beat yourself up just enough to make the next thing better.

How does where you live impact your creativity or work?

Well, I have a phobia about driving, so I’ve never gotten a license. That’s insane because I’m from Ohio. When I was learning to drive, I’d get to an intersection and have a meltdown. (laughing)

This is the perfect city for you then.

Yes. I love New York, and I hate New York. I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with the city. The city lets me be myself, but I’m also not very thrilled with what capitalism does to people and what it’s done to this city in this 1%-has-everything era we live in now. I walk around my old neighborhoods, like the East Village, and it looks like the movie Brazil where there are all these big, shiny buildings.

Yeah, it changes fast.

It’s profound, and it’s starting to really scare me. Now that I’m up in Harlem, I’m officially a gentrifier. It’s weird. New York is kind of like a dominatrix in that, yes, it’s harsh, but it’s so exciting. The only other American city I think I’d really want to live in is San Francisco, but it has the same 1% problem.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community?

Absolutely. People always ask me, “Are you going to move?” I reply, “No, because of what I do I have to be around writers and performers and artists, not just for RISK!, but for being in my community.” That said, almost every three, four, or five years, a new batch of people who went to UCB or The Pit move out to Los Angeles. There are these huge migrations that happen.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I don’t think there is a typical day, except that around 10am I get on Skype with JC and we talk for a couple hours about email, scheduling, and stories. From there, I’ll go train someone or teach a class or work on people’s stories for upcoming shows. At night, I will be doing more of the same—or partying. There is a side of me that wants to be playing forever, that wants to be creating and not grow up. I do a lot of playing at night.

Work hard, play hard, right? Alright, I have one last question for you. What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Legacy! Oh, my gosh! (laughing) Well, I suppose that what I can say is that, during the time I’ve been doing this, the thing I’m the proudest of is when people tell me how the show has helped them. I’ve had people say they were suicidal, and the podcast helped the clouds part because they started hearing about experiences that others lived through. Life can be messy and confusing, but it does get better. Even when I make a mess of my private life or fail to do as much as I want to do creatively, I can say that people were moved and felt more connected to the rest of humanity because of some of the sharing they heard on RISK!—that’s an invaluable thing.

“Even when I make a mess of my private life or fail to do as much as I want to do creatively, I can say that people were moved and felt more connected to the rest of humanity because of some of the sharing they heard on RISK!—that’s an invaluable thing.”