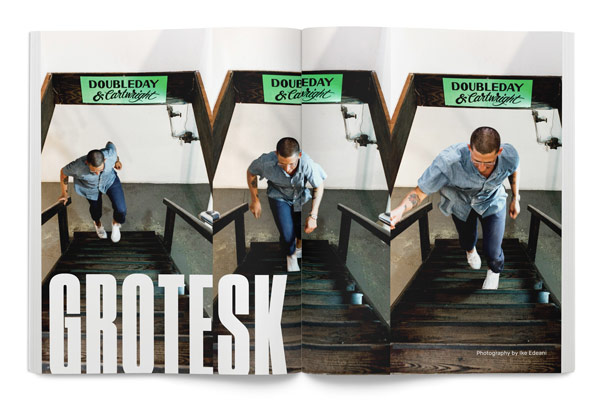

- Interview by Tina Essmaker August 30, 2016

- Photography by Ike Edeani

Grotesk

- artist

- designer

Swiss-born creative director Kimou Meyer, aka Grotesk, recalls how his love of the underground graffiti scene helped form the foundation of his 15-year design career, why creatives should focus on the job instead of the title, and what continues to inspire his lifelong affection for New York City.

Editor’s Note: The unabridged version of this interview appears in Issue 4 of our print magazine. To enjoy the full feature and more photographs, purchase the magazine in our shop. Buy Issue 4.

Editor’s Note: The unabridged version of this interview appears in Issue 4 of our print magazine. To enjoy the full feature and more photographs, purchase the magazine in our shop. Buy Issue 4.

Tell me about your path to what you’re doing now. I was born in Geneva, Switzerland. Both of my parents were architects, and because it was a Swiss household, my family was passionate about minimal design. My mom was also a politician from a leftist party, and my dad was a total anarchist. There was a constant mix of art and politics in the house.

Growing up, I hung out a lot in my parents’ wood shop. My parents frequently built models and drew blueprints for their projects. I spent time drawing with my brother and making things out of wood. Hanging out with my parents in their shop was my first connection to the world of art and illustration.

As I got older, I drew more and more. In high school, I enrolled in an art track, which was basically a four-year program of regular courses with additional hours dedicated to different art mediums. One day, when I was trying to emulate Van Gogh, my teacher told me, “Your work is too cartoony. You should do graphic design instead.” I asked him what graphic design was, and he said, “It’s making layouts and pictograms, like what you see at the train station.” I told my parents, and they recommended that I talk to local graphic designers. At one of the studios I visited, I saw a guy making a poster for a theater and I thought, “Wow. That’s what I want to do.”

After graduation, I started researching art schools. At the time, the best schools in Switzerland were in the German part of Switzerland. I was from the French part, and I couldn’t see myself learning German; I was lazy and wanted to speak English instead. Out of curiosity, I looked at options outside of Switzerland. Back then, Switzerland wasn’t part of the European Union, so I had to pay full tuition at most schools. I wanted to go to school in London, but there was no way I could afford that.

After a lot of searching, I finally found a school in Brussels called L’École de la Cambre. It offered great fashion, communication, and graphic design courses, and tuition was much cheaper. I thought, “I can do that!” So I moved to Belgium and lived there for five years. While I was there, I spent my summers DJing and making flyers and album covers for friends so I could pay tuition. That work ended up being a big inspiration for some of my future projects.

In my final year of school in 1999, I had an amazing opportunity. In the fifth year of the program, students are asked to do a thesis project on whatever they want; then they present the project to a jury before graduation. I decided to focus on typography, so a Swiss friend of mine and I designed five different typefaces. Our project was pretty groundbreaking because we were the first generation of students to use computers.

One of the people on the thesis jury was Dimitri Jeurissen, the creative director and cofounder of a design studio called Base. Their mothership office was located in Brussels, but they were getting ready to open an office in New York. Dimitri saw the project my friend and I had done and asked us, “Why don’t you guys come work in our New York studio?” I replied, “Really? Yeah!” And then I started bugging out.

On October 14, 1999, I moved to New York City. I had never visited before, but as a teenager hip-hop music and skateboarding culture were very important to me. I listened to New York artists like Nas, Biggie, Smif-n-Wessun, and Mobb Deep. I drew buildings and skyscrapers, and I pictured how grimy it was. I had created a fantasy world of what I believed living in New York was all about. Because of that, I wasn’t scared to move to New York: it felt like I was going to my Mecca.

“I worked in fashion, so I was around a lot of nonsense and drama. During a shoot, I heard someone say, “This is grotesque!” And I kind of liked it. The word grotesque means stupid and absurd, but it also refers to my Swiss heritage.”

What kind of work did you do when you first moved to New York? I was worked at Base, where most of our clients were fashion brands and art institutions. Those were the studio’s specialities. For example, I worked for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) when it moved to Queens, I worked with Milk Studios on a large amount of their collateral, and I did campaigns for the Barbizon Hotel. It was pretty high-fashion, luxury stuff.

Parallel to my day job at Base, I did personal design and illustration for street culture brands. In 2000, my wife started working at Alife, the first concept store in New York. No one had done anything like that before. The designer denim brand, Rogan, dropped jeans off there every week; the graffiti artists, ESPO (Steven Powers) and Twist (Barry McGee), had their first pieces hung on the wall there; and Shepard Fairey, aka Obey, had his first New York art show in Alife’s gallery. It was amazing to see that emerging street culture of New York.

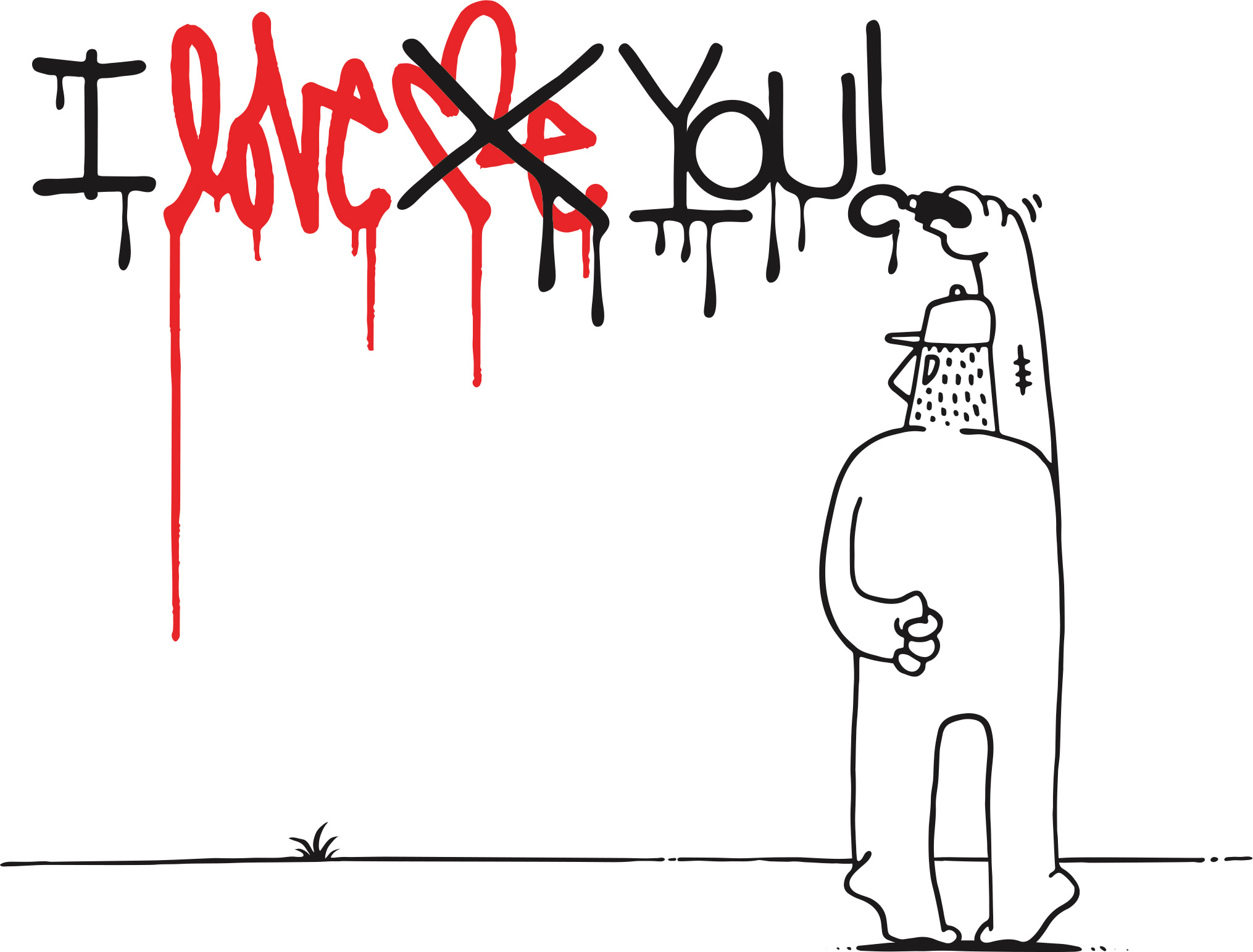

Had you already done work under your moniker, Grotesk, at that time? No. I wasn’t a graffiti artist, but I hung out with graffiti artists through people I knew at Alife. Each artist had a moniker. Rob Jest, the owner of Alife, said, “Kimou, if you want to make it in the art world, you need a name. You can’t just be Kimou Meyer.”

I worked in fashion, so I was around a lot of nonsense and drama. During a shoot, I heard someone say, “This is grotesque!” And I kind of liked it. The word grotesque means stupid and absurd, but it also refers to my Swiss heritage. Where I come from, Neue Haas Grotesk was one of the precursors to the Helvetica typeface, which is one of the most used typefaces in the world—and probably one of the biggest points of Swiss pride. Even the word Helvetica comes from the latin word helvetia, which means Switzerland. So, I came up with the name Grotesk and drew the logo of a guy putting a coat hanger through his teeth because he sold too much fashion—he’s a fashion victim. I continued working my corporate career as Kimou Meyer, and as Grotesk, I could talk shit, make art, and draw t-shirts.

The harder I worked and the more people I met in the street and skate culture scenes, the more opportunities I had to design for magazines and small clothing labels. Right after September 11th, 2001, Marc Ecko, owner of Eckō Unltd., noticed my work. At the time, Eckō Unltd. was still kind of underground, and he offered me a job as an art director. Career-wise, it was a big leap for me, and I was really excited to work with a hip-hop brand. I did special projects with artists like Spike Lee, and I basically helped Marc Ecko run the creative direction of the clothing line.

After three years there, I felt burned out. The clothing was getting baggier, more urban, and ugly. It had lost its streetwear personality. I told Marc, “I love working for you, but I can’t do the baby-blue fleece sleeping bag pants.” (laughing) Coincidentally, Eckō Unltd. had recently purchased Zoo York because it was struggling financially. They needed somebody who understood skate culture, and I was respected by that camp, so they hired me. I served as the creative director of Zoo York for four years, and it was amazing. My whole experience with Eckō Unltd. and Zoo York lasted for about seven years. During that time, I became an expert in pretty much everything from color forecasting to mood boards to merchandising.

A turning point came around 2007 when Zoo York sold their company for corporate reasons. I was faced with the choice of staying with their new corporate owner or leaving with a severance package. My wife asked me, “Do you really want to be making t-shirts when you’re 40 years old?” I think of myself as a goofy teenager, and I believe I will always have that spirit, even when I’m 70. As passionate as I am about street culture, the t-shirt gig was starting to wear on me. I had designed about 500 t-shirts by that point, and I had lost the enthusiasm for it. I wondered, “Maybe it’s time for me to do something different?”

So I spent two years between 2007 and 2009 freelancing and searching myself. I decided that I wanted to start an agency. I tried starting one with a friend, but it didn’t work out because he and I had too much of the same personality—we were both lazy on the business development and only wanted to create. One day, one of my current partners, Chris Isenberg, was playing softball in a nearby park. I complimented his t-shirt, and he told me that I was actually wearing a t-shirt that he designed for a company called No Mas. I said, “No way! You’re No Mas?” When I told him I was Grotesk, he said he was a fan of my work, and we randomly clicked.

A few weeks later, I got a call from Nike to come in for a meeting about a project. Coincidentally, Chris was also in the meeting. I saw it as a sign. At the time, Chris had a business with a designer named Aaron Amaro. I didn’t have an office, so Chris said, “Why don’t you come work on this project in our office?” The office was literally two shipping containers on a rooftop—it was tiny. They had two graphic designers and an account manager and had been taking on corporate, sports-driven projects. One day, Chris, Aaron, and I were talking and decided to become partners and do something a little bigger. Aaron came from a traditional ad agency; Chris was a writer; and I was a creative director from the world of fashion, culture, and graffiti. We were all different, so it was a perfect combination.

We started our creative agency, Doubleday & Cartwright, in 2009, and it took off quickly. The project for Nike worked out, and they gave us six months worth of work. That allowed my partners and I to find an office—my wife actually found our current space in Williamsburg. In a short period of time, we grew from three partners and two designers to five people, then six. Now we have twenty-five people in our New York office, three people in our LA office, and we are going to open another office somewhere else soon.

“Everything cross-pollinates. Outside of Doubleday & Cartwright, I still make personal art as Grotesk. I lock myself down for two hours and draw or cut wood or sculpt, because I’m crazy and I love working too hard.”

Your agency also puts out self-initiated work, like Victory Journal. How did that come about? In 2012, we started a sports and culture publication called Victory Journal. The idea came from our respective passion for sports. We felt like there was a lack of storytelling in the aesthetic of sports that wasn’t communicated by any media. For us, it’s about the untold story. How can we photograph a basketball game that has been shot thousands of times and make it different? That was the challenge. Even though Victory Journal started as a passion project, it has become a real business venture. We now have an online platform, we’re about to release the next issue, and we have a lot of people who want to work with us because of it.

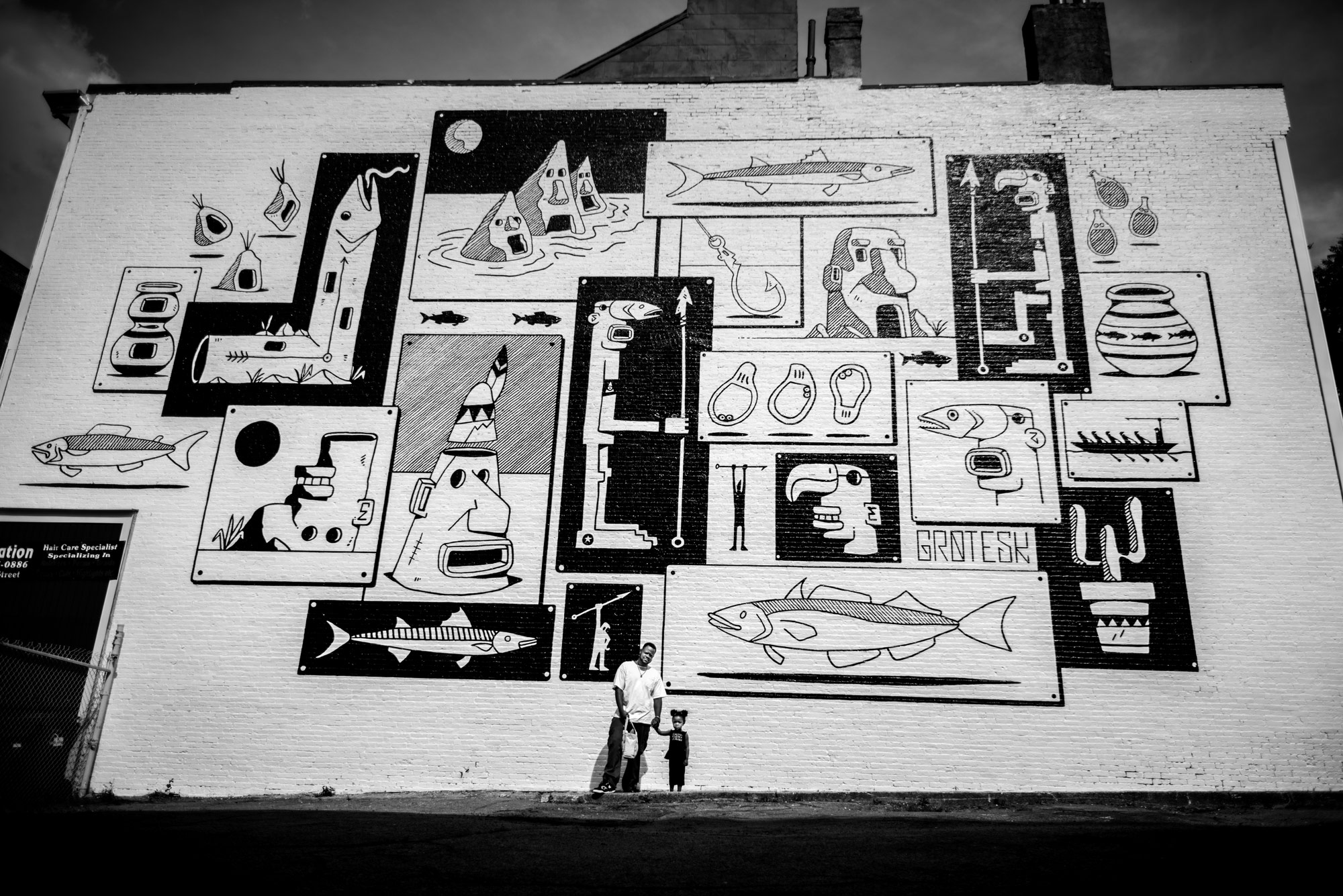

In addition to being a partner at Doubleday & Cartwright, you still create work under the Grotesk name, right? Yes. Everything cross-pollinates. Outside of Doubleday & Cartwright, I still make personal art as Grotesk. I lock myself down for two hours and draw or cut wood or sculpt, because I’m crazy and I love working too hard. (laughing)

Having the Grotesk name out there helps things come together organically for work, too. I might call an artist friend who will refer me to another artist for a project. It’s amazing how interconnected these networks are. It’s a rite of passage: if somebody says you should talk to someone, then they have that person’s blessing. After 15 years, my partners and I have a network of 200 or 300 artists who we work with often. It’s very community-based. That’s the reason we’re at the point we’re at now: we love engaging people, bringing them in to contribute their skills, and mixing everything together with our storytelling voice.

What is the biggest risk you’ve taken so far? My biggest risk is raising a family in New York. (laughing) It’s expensive and challenging. I have an easy job—my wife is the one who deserves all the credit. As corny as it sounds, she’s the real worker. I come home wiped out after a day of work and meetings, and the next thing you know, dinner is ready, the kids are chill, and I can hang out without having to think about anything. My wife has also known me for so long that she can give me both very positive and very critical feedback. She’s the only one who can tell me, “I hate that. It’s ugly.” And if she says that, then I know it’s ugly.

I grew up with a lot of compassion and generosity around me. Now, you can take that with a grain of salt considering my sarcasm: I grew up in a family that talked shit and debated all of the time. But I’ve also realized that if you have a home and food to eat, then nothing is that big of a deal. You’re okay. I can’t say that I take any big risks because what I do isn’t brain surgery: we sell sportswear or make a music festival a great experience. People like to consume those things, but it’s not risk-taking. If we have a tough month, we have a tough month, but it’s still much easier than what a lot of people around the world have to deal with.

As far as taking creative risks, I don’t know. I believe risk-taking is more about daring to try something new. You don’t want to be pigeonholed as the person who’s only known for one thing. Some people are one-trick ponies who don’t know how to reinvent themselves, and that is sad. It’s now common for somebody to find a style or aesthetic and juice it, juice it, juice it. The risk is saying, “Okay, let’s try something else.” If you travel and meet new people, that’s going to feed into your work. Don’t constrain yourself to the same cycle of people; try to go out and meet new people. It’s important to have those human interactions outside of your job and social media.

Are you creatively satisfied? Never, but that’s a blessing, even if it makes me want to bang my head against a wall sometimes. I’m not satisfied with anything. (laughing) However, I’m good at letting go of perfectionism, even though I tend to be pretty self-critical of my personal work. I’ll look at it a week later and find flaws.

This isn’t a regret, but at a gut level, I wish I could be a full-time illustrator or artist. Maybe it will happen one day, but right now I feel fulfilled because I probably have one of the best jobs in the world. I get to wake up every day and do what I love—whether you’re a chef or a designer or a plumber, that is a blessing.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out? Seeking self-satisfaction on social media is a huge danger. You can get a pat on the back for your work very quickly, but then find out that it’s coming from some 13-year-old and not a business owner who wants to work with you. If you experience too much of that, you start becoming delusional about being the shit and believing that people are familiar with your work when they really have no idea. Instead, you need to focus on building a strong portfolio and body of work, even if it’s still kind of sloppy and imperfect.

The most important piece of advice comes from many conversations I’ve had with my peers who studied in Europe and are now working in New York. In Europe, graphic design or art direction is considered a job, not a career. Over there, you learn about design the same way a baker learns how to bake bread: you go to a graphic design school to be a graphic designer. In purely theoretical school systems, you don’t learn to create your own style—you learn how to answer everybody else’s style. You are trained to answer any communication and visual language challenge.

Nowadays, designers are focused on standing out from the crowd. But does that mean they know how to be a good designer? No. Sometimes I see kids’ business cards that say: “I’m the CEO, VP, and creative director of my company.” A VP, CEO, and a creative director? Those are all crazy, full-time jobs! (laughing) I say to them, “So, you’re basically a freelance graphic designer?” And they respond, “Yeah, I work for myself.” Well then strip all of that other shit out and be honest! We’re not buying it. The race for a title here is crazy, but as I keep telling my team: the day you become a creative director is the day you don’t design anymore. If you look at the title, you direct creative. That means that every day you look at things and say, “Yes. No. Let’s try this. Change that.” Then you deal with the budget and communicate with the clients.

“I believe risk-taking is more about daring to try something new. You don’t want to be pigeonholed as the person who’s only known for one thing. Some people are one-trick ponies who don’t know how to reinvent themselves, and that is sad.”

I’d tell young designers to focus on creating a body of work without putting all of it out on social media every day. If you wait, you’ll have a bigger impact. When I see somebody talented, it’s typically someone I’ve never heard of. All of a sudden, I ask, “Who’s this guy with all of these amazing illustrations?” He’s a smart guy because instead of putting out 20,000 Instagram posts, he waited to put out a body of work all at once. I think people have a fear of missing out if they’re not constantly posting something.

Something else I find interesting is that just because someone has 10,000 followers or 200,000 followers doesn’t mean they know how to monetize it. Some people forget that it’s just a number. Social media narcissism is everywhere now, but it’s important to be a part of those networks because it’s how people work.

How does living in New York influence your work, and how does it differ from how you grew up in Switzerland? Like I mentioned before, New York has been an obsession of mine since I was a little kid. I remember being fascinated by pictures of Tokyo, Paris, New York, and other urban landscapes. I even liked the big, metropolitan areas in movies like Blade Runner and Star Wars. American hip-hop culture also had a big influence on my life. When I first landed in New York, I took out my CD player and put on Gang Starr’s “Mass Appeal” while I walked along the Brooklyn Bridge. I almost cried tears of joy looking at the Twin Towers and thinking, “I made it! I’m in New York!”

It’s funny because I arrived in New York at a time when it was becoming a lot safer, while Geneva and Brussels were becoming worse and worse. (laughing) I expected New York to be shitty. Meanwhile, back in Belgium, I had been robbed, beat up, and had my apartment broken into. I thought, “Wow, at least that Rudy Giuliani did clean the city!” I’m not saying it’s a good thing, but I did start to feel more confident about going wherever I wanted in New York. I became like an anthropologist; my world was fed by the city, its people, conversations, signs, architecture, energy, food, and ethnicities. I wanted to see everything.

Someone told me, “If you’re still in New York after 10 years, you’re most likely a New Yorker.” A lot of people come to New York to make it, but the minute they do, they’re out. I have a lot of friends who came here, tried, and failed because it was too hard for them. This city looks pretty on the surface, but you need to have a tough skin to be here. If you embrace it and have the luxury to escape it once in a while, it’s the best place to be in the world. I haven’t been anywhere else that I would call home.

“…I feel fulfilled because I probably have one of the best jobs in the world. I get to wake up every day and do what I love—whether you’re a chef or a designer or a plumber, that is a blessing.”