- Interview by Tina Essmaker December 16, 2014

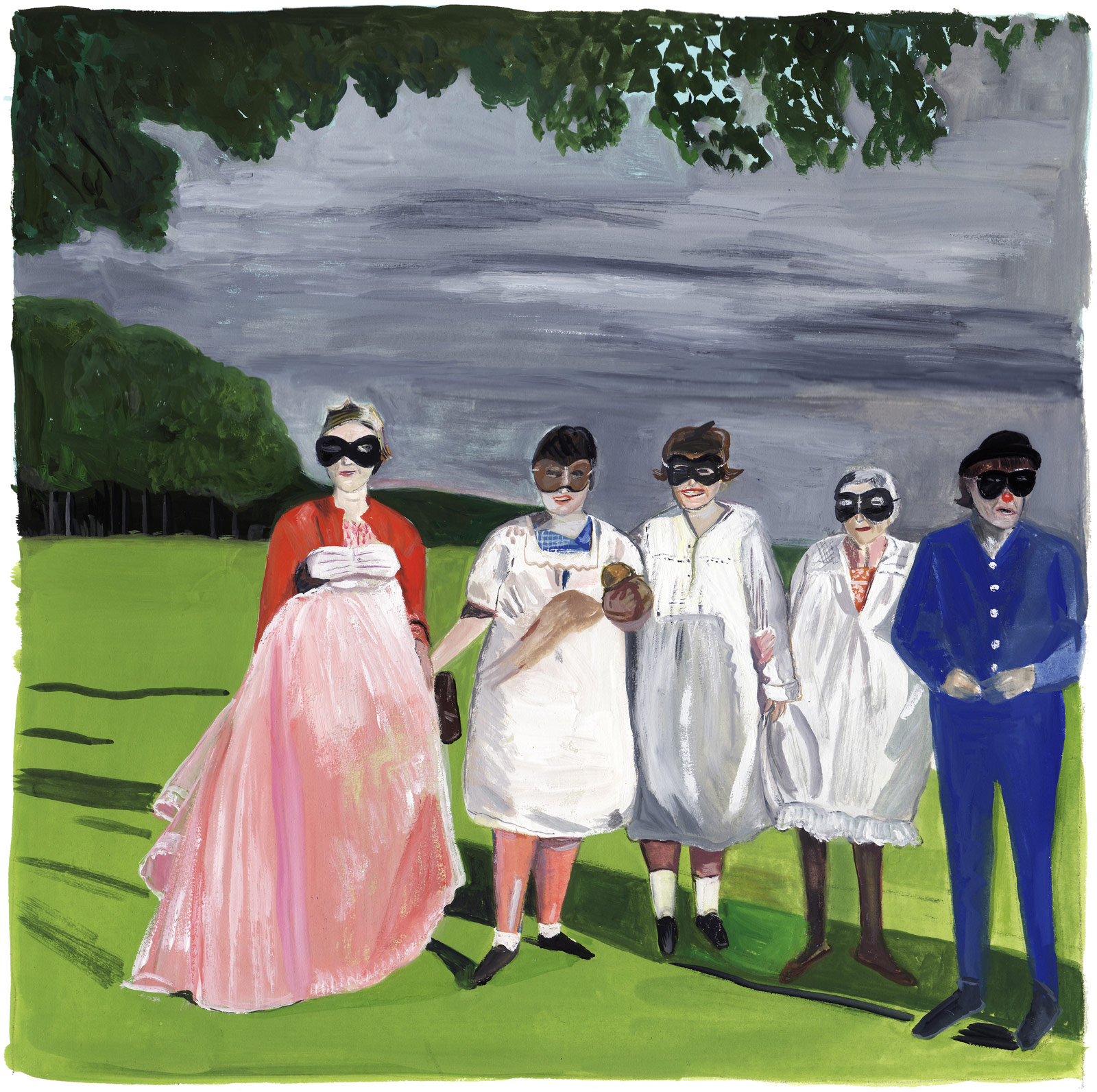

- Hero illustration: Self-portrait with Pete by Maira Kalman

Maira Kalman

- artist

- designer

- illustrator

- writer

Maira Kalman is an artist, author, designer, and illustrator, who was born in Tel Aviv. She moved to New York with her family at the age of four and was raised in Riverdale, the Bronx. Maira has written and illustrated eighteen children’s books and five books for adults. She created two monthly online columns for the New York Times, is a contributor to the New Yorker, and has undertaken collaborations with composer Nico Muhly and author Michael Pollan. She lives in Manhattan.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

The path started in Tel Aviv. Well, actually it started in Russia with my parents, who left their country to go to Palestine. I was born in Tel Aviv, and then my family moved to New York when I was four years old. My path was about leaving home, coming to a new place, and being an outsider. But it was also about having a good sense of self and a good feeling about the world, so New York didn’t seem too scary.

The creative path was that I knew I wanted to be a writer when I was a child. That came from—well, where does anything come from? I don’t know, but I did read a lot. When I became disenchanted with writing, I wanted to draw. I always knew that I would somehow be expressing myself, and that’s what I did, along with being a waitress once in a while.

Was it a long path to sustaining yourself as an artist and writer?

I think I’m incredibly lucky because I had the patience and perseverance and single-mindedness to believe that I belonged in that world. It took a very long time to become an illustrator, and I had all kinds of odd jobs along the way. However, I had the good fortune to meet a man who had the same kind of philosophical outlook that I did: we were both curious and had a sense of humor, and we believed we could do whatever we wanted. For us, New York was an optimistic place. Yes, it can be a very difficult place, but we thought there was nothing we couldn’t do—it would just take time. So we found our way by working hard.

Historically, we were in the right place at the right time. There was an audience for the kind of work we wanted to do, and there was the ability to make it happen.

In more detail, what was your journey like from finishing school up until now?

In the 1960s, I went to The High School of Music & Art, which is now the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts. I studied music, which was something I loved very much. Then I attended New York University (NYU) in the late ‘60s, which was a turbulent time; people were trying to blow up the university rather than go to school. There were anti-war sentiments, feminism, and this counter-culture, and ugly bellbottoms—all the things that made you think the conservative world was about to topple. There was a lot of interesting stuff going on.

I met the man who would become my husband, Tibor Kalman, in college. He was a journalism major, and I was an English major, but we both dropped out. Tibor got a job at a bookstore at NYU. One day, the window dresser was sick, and Tibor said, “Oh, I can do that.” He went on to become an incredible graphic designer, journalist, and editor. He and I were always working together, and, at the same time, I was starting to draw and wanted to do editorial illustration. We both traveled in this path together, getting any work we could. We eventually got more work that we were in control of, that we were the authors of. It then became about the content and doing something irreverent and unusual, but communicative.

“[Tibor and I] were both curious and had a sense of humor, and we believed we could do whatever we wanted. For us, New York was an optimistic place. Yes, it can be a very difficult place, but we thought there was nothing we couldn’t do—it would just take time. So we found our way by working hard.”

In 1979, Tibor founded M & Co. There were many wonderful designers there, and I was one of the people who worked with him, either up front or behind the scenes. Our dialogue went on all the time; sometimes I was actively working on things, and other times I was behind the scenes. Tibor’s fame grew and his work grew, and then we had two children. That’s when I started writing children’s books.

I illustrated my first book in ’86 with David Byrne—the Talking Heads were clients of the studio, so there was a connection with David, and it was the right time. The Talking Heads album, Little Creatures, had just come out and our book, Stay Up Late, was a little new-wavish; it was a new kind of illustration that was more personal and more eccentric. The books continued, and then I started being interested in doing journalism for magazines. I began writing about my travels and painting, and that started to grow.

It was about being curious about something, wanting to do it, and asking, “How would I do that?” I talked to as many people as I could and asked, “Would you like to hire me to do a magazine piece?” Little by little, people said yes because it was a different take than what you’d normally see for a story. For example, I’d cover fashion shows in Paris for the New York Times or the Carnivale in Venice for Departures. Pictorial essays are really wonderful to do.

I like what you said earlier about knowing that you wanted to be a part of this world from an early age.

Whenever anyone asks me, “What will happen? How will I do in this world?,” I say I don’t know. You’ll either do it or you won’t do it; you’ll stick with it or you won’t; or something else will happen to inform it. There’s no prediction. You have a feeling and you try to do the best you can.

It sounds like creativity was part of your childhood. Did your parents encourage it?

My mother encouraged my creative life. She took me to concerts and operas; she took me to the library and we sat together and read. I had piano lessons and dance lessons. My mother’s world of learning was very acute. She wasn’t an artist; she was a homemaker, but she was quite gorgeous and amazing and interesting. For me, she was very much a model of a person who had great integrity, honesty, and said what she thought.

There were never any conversations or assumptions about what I should do in my life. We all just lived, and everybody did what they did. That’s a hard thing to do when you have kids because you want to tell them what to do; restraining yourself is hard. My encouragement came not from being told to try this or that, but from being loved and told that whatever I did was great.

Did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew what you wanted to do?

In my memory, which might be faulty, (laughing) it was when I read Pippi Longstocking around the age of seven. That was when I understood that this was something a person could do, that you could write a children’s book. I thought, “That is exactly what I’m going to do.” It took a while to actually get around to it. I made some detours by becoming an illustrator first. But that was an “Aha!” moment.

There were others, of course, but having children was a tremendous moment of discovery of a world that made so much sense to me in its whimsy and imagination and love. It was a world I wanted to have a dialogue with.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

Well, my biggest mentor, besides my mother and the other women in my family, was my husband. Tibor and I grew up together, and I learned a tremendous sense of work ethic and fearlessness from him. I’m not saying I don’t have fears—I have many, many fears. But Tibor was the kind of person who said, “You can have an idea. That’s fine, but why don’t you make the idea happen,” which is a whole other thing to do. His belief in work and in finding yourself through work was an extraordinary learning for me.

Have you taken any big risks along the way?

For me, every project is a risk because I’m really concerned about it being wonderful as opposed to “just fine” or “good enough.” I always feel like there’s a standard I won’t live up to or that I won’t satisfy myself. Of course I see the flaws in everything I do. On one level, that keeps me alive and alert and awake because there isn’t the complacency of already knowing how to do something. Every project is a big deal for me, and I have as much angst as I did in the beginning of my career. But I also have a little bit of experience and know that I will most likely find my way.

“Tibor and I grew up together, and I learned a tremendous sense of work ethic and fearlessness from him. I’m not saying I don’t have fears—I have many, many fears. But Tibor was the kind of person who said, ‘You can have an idea. That’s fine, but why don’t you make the idea happen,’ which is a whole other thing to do.”

The tangible things I’ve done, like working on the opera, The Elements of Style, with Nico Muhly, have been a moment of transition, of going to another place, of not knowing what I was doing. Nico, a brilliant composer, created a song cycle based on The Elements of Style; we worked on it together in terms of the text and what the whole evening would be. Then we did another piece from The Principles of Uncertainty. Entering into that world and not knowing what the outcome would be was a big risk.

I performed as the duck last year in Isaac Mizrahi’s production of Peter and the Wolf at the Guggenheim. I was wearing a tutu and flippers and it was a grand, buffo role. Being on the stage took me back to when I was a child and took ballet lessons. There is a performing aspect to being an illustrator and writer. Your work is out there for the public and there’s a connection to performing. It feels natural, but also like, “Uh-oh. What am I doing?”

Now, I’m beginning to walk in the world of dance and collaboration with choreographers. That is another risk. I’ve had dreams about it where I’m outside naked. My daughter said, “Well, you’re exposing yourself. It’s scary.” What’s the worst that could happen? It could fail. I don’t jump at the chance of failure, but I think that those elements in work feel the most like you’re making a leap into a different place.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Well, I have a desire to work on interesting creative projects that will take me from the printed page to the stage. I don’t have any message; I don’t want to work in any arena to teach or convey anything. I just want to do my work.

Are you creatively satisfied?

It’s a double-sided story. I feel tremendously satisfied because I have the most incredible projects. Basically, I’m told to be myself and let others know about it—it’s a complete dream. On the other hand, there are always the worries of is this interesting? Is it smart? Is it funny? And what’s the next thing? It’s not static. Everything changes, every day, which is the glory and curse of things. You can’t rely on anything, but you can rely on navigating through it all—or at least one hopes.

Are there projects you’d like to explore in the coming years?

The dance projects with two different choreographers are things I’m going to explore in the next two to three years. I’m probably doing too much, which is a New York syndrome—I should write a book called One Thing at a Time. Of course everybody confronts that; we have a limited amount of energy in this world—what will we do with it? I think that taking on those choreography pieces might really take over my life because I throw myself into things. But I do also want to travel and spend more time walking around the world.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

It’s a terrible thing to give advice. I’d say that you have to try to be true to yourself and find out who you are by doing the things that give you the most pleasure in life. Try to weave that into your work; don’t separate yourself into different beings. But people starting out who are in their twenties? That’s a rough time. Stick with your vision, if you can, and find people to love you, if you can.

You grew up and stayed in New York. Are most of your family and friends here?

I have a very beautiful family in Tel Aviv, who I visit as often as possible. They are a tremendous bedrock of happiness and love. But my children and friends are here in New York.

Tibor and I lived in Rome for two years, and I think I could live in Rome or Tokyo, but I don’t know how I could possibly leave New York. However, you do have to escape New York, which is why everybody leaves on the weekends. It’s great to leave, and it’s great to come back. Whenever I leave and return, I say, “Thank god for New York!” It’s wonderful.

How does New York influence you?

I love to walk, and this is the best walking city in the world. There is more inspiration in a walk around the block than I could ever catalogue. I could write a book about every walk I take. Besides being the cultural center of the world and home to all of the museums I live in, the the eccentric energy level of the city is fantastically inspiring. I can walk down the street, clear my head, and come back with most problems solved. For me, the best time is when I’m alone and don’t expect anything, but then an idea comes.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community?

I’ve had that from the beginning. I’ve always been drawn to people who are interesting and who have fun. I have an amazing community of friends; some are in the arts, and some are not, but they’re all people who are having an interesting time.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I wake up early, go for a walk in the park or meet a friend for a walk. Then I go to my studio in this building on the ninth floor, and I work with no distractions. Then there’s traveling, going to museums, having meetings here and there, although I try to limit things to the bare essentials, and to what’s fun. That’s my day, which ends with going to bed early. I don’t work at night. I’m happy to read or watch a British murder mystery, be deliriously happy in bed, and then wake up early the next day.

Is there any music you’re enjoying right now?

There’s a lot of Bach going on in my life right now. My children gave me the entire box set of Bach, which I’m listening to in a continuous loop. But I just heard a performance of the Philip Glass piano etudes and I think that will be on continuous loop for a while.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

When the BBC does a Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple show, I’m there. There are a million movies, but if I had to tell you the genre, it would be 1930s madcap comedies, like Bringing Up Baby with Katharine Hepburn and Carey Grant, and My Man Godfrey with Carole Lombard and William Powell.

Your favorite books?

Well, in terms of novels, I love Nabokov, Jane Austin, and WG Sebald, but if we were to talk about my favorite photography books, then I’d say Diane Arbus and August Sander. I also have a million fashion and architecture books. I love each and every book I have.

What’s your favorite food?

Any kind of pasta, anywhere, anytime.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

A joy of living, despite tragedy.

“Whenever anyone asks me, ‘What will happen? How will I do in this world?,’ I say I don’t know. You’ll either do it or you won’t do it; you’ll stick with it or you won’t; or something else will happen to inform it. There’s no prediction. You have a feeling and you try to do the best you can.”