- Interview by Tina Essmaker November 27, 2012

- Photo by Alissa Walker

Maria Popova

- editor

- writer

Maria Popova is the founder and editor of Brain Pickings, has written for Wired UK, The Atlantic, Nieman Journalism Lab, the New York Times, and Design Observer, among others, and is an MIT Futures of Entertainment Fellow.

Interview

Describe your path to what you’re doing now as an editor and writer.

I started Brain Pickings when I was still in college because I felt unstimulated by the experience of higher education. The enormous lecture classes of 400 people, professors who didn’t know students’ names, reading off of PowerPoint presentations, and assigning reading to be done at home—none of that was my idea of personal growth and enrichment. I started learning and reading about things on my own and Brain Pickings was a record of that.

At the time, I was also paying my way through school by working at a small ad agency, in addition to three other part-time jobs. I noticed that what the guys were circulating around the office for inspiration was stuff from within the ad industry and I didn’t believe that was how creativity worked. I started sending out an email every Friday including five things that had nothing to do with advertising, but that I thought were meaningful, interesting, or important—and not just cool. I noticed that the guys were forwarding those emails to other people and I thought that maybe there was an intellectual hunger for that sort of cross-disciplinary curiosity and self-directed learning.

On top of my four jobs and full university course load, I enrolled in a night class to learn very basic web design and I took Brain Pickings online. That was before WordPress was mainstream, so I was hard-coding static HTML pages every Friday, taking them down, and putting up the new ones. Eventually, I moved it over to WordPress and it’s grown pretty organically. I’ve never been too strategic about it and that whole game of social marketing is something I’ve never been deliberate about. To this day, I just write about things that interest and inspire me as well as things that I think are important to be preserved. That’s that, I guess.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Bulgaria and grew up there. I moved to the US for college.

How was creativity a part of your childhood there?

I’ve always been very visually driven. Bear in mind that I grew up during communism and during my early childhood, there wasn’t much available; I didn’t have crayons or a lot of other things. Perhaps the best present ever given to me was from my uncle, who is an architect. Right after communism “fell”, he gave me a drawing kit that came in a suitcase and had crayons, pencils, rulers, watercolors, and other paints.

I didn’t read a lot myself, but my grandmother, who is very intellectual, would read to me. I was also very fascinated by her encyclopedias—she had a whole collection of them. With the Internet, I think we’re losing the ability to learn about something random that we didn’t know we were looking for. That’s what encyclopedias are great at.

Did you have an “aha” moment when you knew that editing and curating, for lack of a better term, was something you wanted to do?

Not at all. I also don’t believe in the terrible, toxic myth of the “aha” moment. Progress is incremental for us, both as individual creative beings and together as a society and civilization. The flower doesn’t go from bud to blossom in one spritely burst. It’s just that culturally, we are not interested in the tedium of the blossoming. And yet that’s where all the real magic is in the making of one’s character and destiny.

“Progress is incremental for us, both as individual creative beings and together as a society and civilization. The flower doesn’t go from bud to blossom in one spritely burst. It’s just that culturally, we are not interested in the tedium of the blossoming.”

I really appreciate what you just said. We see people who are successful and often think it happened overnight, but that’s usually not the case. Individuals, especially young people starting out, seem to believe that their careers should take off quickly and when that doesn’t happen, they get discouraged. But there’s a lot of hard work that has to be put in behind the scenes and no one is necessarily going to commend you or say, “Great job. Keep going.” You just have to keep doing it.

Yeah, it’s funny. Right before this interview, I was over at Hyperakt, the design studio. They do these great lunch talks and my friend Debbie Millman, who runs the wonderful Design Matters podcast, spoke today. At the Q & A after her talk, she cited this anecdote, which is basically what you just said. She had just given a talk at the Tyler School of Art and this young student asked, “How do I get people to visit my blog? I’m very frustrated with it.” Debbie asked her, “How long have you been doing it?” and the student sincerely and earnestly replied, “A month.”

I think if you have a great idea and are intelligent and articulate about it, people will gravitate toward it sooner or later. But also, I’ve been doing what I do for seven years and I never started it with the notion that it would be my life. It is my life now and it will continue to be, but I couldn’t have predicted it. I don’t believe that the best work happens when you gun for a specific outcome—I just don’t think that’s how it works.

You mentioned that you’ve been doing Brain Pickings for seven years. For our readers who might not be familiar with it, would you elaborate on how it’s grown over the years?

Conceptually, it has changed very, very little. Granted, I’ve grown a lot as a person and because it’s such a personal thing, my interests and my intellectual and creative curiosities have changed. However, the nature of what I write about and more importantly, why I write about what I write about has not changed.

Technically speaking, the platforms have changed as it started with an email newsletter, went to an HTML site, and then to WordPress with some cosmetic redesigns along the way. I also have a newsletter again, which was almost an afterthought. In 2009, a friend nudged me to do it and now it’s become pretty sizable. It’s strange because the demographic of people who read Brain Pickings is very diverse, so I get high school students, but also—and I don’t know why—I have a pretty large chunk of older people, including a large portion of retired educators. Now, many of the people who subscribe to the email newsletter are older and many of them don’t realize the newsletter is based on the site or realize that the site even exists.

Observing this organic journey has been very educational in understanding how people relate to knowledge and how they choose to absorb what they absorb. My philosophy and the one thing I’ve been strategic and deliberate about from the beginning is reader first—I don’t want anything to tell people how to engage with what they want to engage with. I don’t believe in slideshows, pagination, truncated RSS feeds, paywalls, and all these things that basically punish your most loyal readers. I’m just one person; I can’t optimize everything to be perfect, but I’ve tried to make things as seamless and easy and digestible as possible. At the end of the day, Brain Pickings is about the ideas and content and not at all about the bells and whistles surrounding it.

I like that you’ve made Brain Pickings accessible to everyone.

Yes. Well, I guess there are two things I’ve been very strict about since the beginning. The first I already mentioned and the second is that I don’t run ads; I don’t believe in ad-supported media and journalism, so the site is funded by readers through donations. I’m a big believer in the “pay what you will” model; if you see value in it, you give whatever value you see. I think this model incentivizes integrity and encourages people to do work they actually care about.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

Not directly that I can think of. There are people whose work I admire in different ways, but no “mentors” per se.

“…I think you need to be a little in love—not necessarily in a romantic sense, although that helps—but to be in love with the reality of your own life in order to produce beautiful and meaningful and intelligent things creatively.”

Has there been a point in your life when you decided you had to take a big risk to move forward?

Professionally, yes. When I graduated college out of the factory that is the Ivy League system, all the recruiters came to offer students big, corporate jobs. Of course, I had all these offers in marketing and management and banking. It was interesting because it was a risk in the sense that I grew up being really financially challenged and my family was still in Bulgaria, a country on a very different income scale, and they were not well off either. To them, getting a job offer with a big paycheck attached to it was a big deal. Those were numbers that would be a fortune in Bulgaria. But for me, the consideration was, “Do I want to bury myself in a corporate job that I’m going to spent 80% of my waking hours at, be miserable, and hope that the money it gives me will make the other 20% of my life better, even though I’m angry and tired and burned out? Or, do I want to do something that makes me happy to wake up to and happy to go to sleep having done and let the financial part figure itself out?” I turned down all the job offers to the shock of my family.

In fact, when I was first running Brain Pickings in my sophomore and junior years of college, I already had a bunch of job offers. What’s funny is that I couldn’t afford to take that basic web design night class I mentioned earlier. In order to pay for it, I saved money by eating store brand oatmeal and canned tuna for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for three weeks until I had enough money to pay for the class. (laughing) That didn’t feel like a sacrifice or risk at the time—it just felt like what I needed to do to be happy and I’m glad I did it. I can’t imagine having done it any other way.

Where did you go to school?

UPenn.

Did you move to New York after school?

No. I stayed there for about a year working at that creative shop where I started Brain Pickings.

In the past decade, my life has been plagued by immigration bullshit and bureaucracy. In 2007 and 2008, there was this thing nicknamed Visa Gate, which was a government goof that affected two-thirds of people working on H–1B Visas here. That was the type of visa I was trying to get, so I was affected and had to pack up my entire life, say goodbye to my friends, and leave. I went back to Europe and lived in Bulgaria, but also spent quite a bit of time in London. I was in exile there for a little over a year until I couldn’t take it anymore. Culturally, it was draining me; it was so negative and the people and ideas and events I wanted to be around were ten time zones away.

Eventually, I got an offer from an ad agency in LA and even though I didn’t want to work in advertising, it was a way in. Also, it was so loose; they just basically wanted me involved and I was able to create my own job. They were really smart and good people, but I had a cognitive dissonance with being in advertising. So, I moved to LA without having ever been there and having always loathed it from a distance. On day two, I just knew it wasn’t my thing. I’ve chosen not to drive; I don’t want to learn. Instead, I bike. After being a cyclist in LA, I have a body full of marks to show for it. I also felt lonely, isolated, and unhappy there.

Laurie Coots, the CMO of TBWA—the agency—took me under her wing and helped me move to the New York office. She was so gracious about all of it and made sure I was happy. After I moved to New York, there was such a shift in my quality of life—there was creative stimulation and a massive exhale because I was no longer feeling isolated.

The other thing is that I love books. Between the time I left Philly and the time I moved to NY, I had lived in 12 apartments in five cities, on two continents and three coasts—all in less than two years. When you move that much, you can’t have books. All my books were in storage and I wasn’t getting new books. In the year I spent in Bulgaria, I couldn’t even get eBooks; there wasn’t an iPad then. I felt deprived. Once I moved to NY, I got all my books back and I started getting a ton of new books. Now, I’m buried in books.

So now you’re staying put in NY?

Well, I just dealt with another immigration issue in the spring when I quit the ad agency and tried to transfer my visa to my new employer, an education startup called Lore. Transferring your visa is supposed to be a seamless process, but something went wrong and I lost it and had to leave again. Thankfully it was resolved fairly quickly.

It is a really disorienting thing to feel like everything you’ve built for yourself—your whole life—can be pulled out from under your feet by no fault of your own. It’s an arbitrary force that’s always there and it’s really, really frustrating and disempowering. If it were up to me, I would never move away from NY, but I don’t trust the immigration system at all, so I’m cautious.

“…our first responsibility is to ourselves—to be true to our sense of right and wrong, our sense of purpose and meaning. That’s how we contribute to the world. Anyone who is able to do that for him or herself is already contributing a great deal of human potential into our collective, shared pool of humanity.”

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

My friends, the only important people in my life, I’ve met through what I do. They’re absolutely supportive.

My family tries to understand it and they’re always supportive, but I’m not convinced they actually get what it is I do. I don’t even know how to articulate it to myself most days, but that’s okay because I don’t need to. I just need to do it and be fulfilled by it and for them, that’s enough.

Are you at Studiomates?

I am in theory, although I’m so busy that I’m barely there. Tina jokes that I use it as my mail room. (laughing) It’s so close to where I live, but it’s just that every second is accounted for somehow.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Well, isn’t that every person’s ultimate measure of happiness on some level, consciously or subconsciously? It’s very challenging to talk about these things that are very deep and existential without it sounding contrived or dishing out clichés, but at the end of the day, the reason clichés exist is that they’re true. That’s all one big disclaimer to what I’m about to say, which is that I truly, truly believe that our first responsibility is to ourselves—to be true to our sense of right and wrong, our sense of purpose and meaning. That’s how we contribute to the world. Anyone who is able to do that for him or herself is already contributing a great deal of human potential into our collective, shared pool of humanity. That’s my litmus test, I guess.

Are you satisfied creatively?

Oh, completely.

That said, is there anything you’re interested in exploring in the next 5 to 10 years?

Well, like I said, I don’t believe in planning for things. I believe in doing what inspires you and seeing how it grows organically.

If you could give a piece of advice to a young creative starting out, what would you say?

Again, this is a cliché, but it’s been true for me. Don’t let other people’s ideas of success and good or meaningful work filter your perception of what you want to do. Listen to your heart and mind’s purpose; keep listening to that and even when the “shoulds” get really loud, try to stay in touch with what you hear within yourself.

You’ve talked a lot about New York. How does living there impact your creativity?

The novelist William Gibson has a wonderful term, “personal micro-culture”, by which he means all the things you surround yourself with—people, books, and any kind of ideological input. Those things essentially shape what you think and care about. Living in NY, my personal micro-culture is that much richer. But mostly, I don’t have a separation between work and life; I don’t believe in the idea of work-life balance. The people in my personal life are also very much entrenched in what I do professionally and creatively. Being in NY and not feeling isolated is wonderful. Having true friends who are aligned with what I care about, but who are also different enough to broaden my curiosity and worldview, is enormous to me. I’m so grateful for it every day.

It sounds like it’s important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Yes, but I’m wary of the word “community” because it sounds very organized. I think there’s a value in surrounding yourself with people who stimulate and challenge you, who don’t just agree with you all the time. But I think the most important thing is to feel safe, seen, and understood by the people around you. I believe it was Bill Nye who said this—everyone in your life knows something you don’t. And I believe it’s important to live in that unknown and to welcome and celebrate it. That can only happen when you actually come into contact with people and not in superficial ways, but when you deeply connect with them. That’s really important to me.

I agree. It’s about those meaningful, face-to-face connections, which have been really important for us since moving to New York and meeting people who we can connect with beyond online interactions. That’s been life-giving for us.

I think that’s so, so important. It’s funny because, in the past year, I’ve been the subject of some online trolling and a lot of it tends to be personal rather than ideological. One thing people would throw out a lot is, “All this time on Twitter—you don’t have a personal life,” or conflating being active on the social web as reducing all of your social life to that. I kind of chuckle at that stuff because I am so profoundly grateful for my friendships and the deep relationships I have in my life are the reason for everything for me. Kurt Vonnegut said, “Write to please just one person,” and I think you need to be a little in love—not necessarily in a romantic sense, although that helps—but to be in love with the reality of your own life in order to produce beautiful and meaningful and intelligent things creatively.

“Having true friends who are aligned with what I care about, but who are also different enough to broaden my curiosity and worldview, is enormous to me. I’m so grateful for it every day.”

This might be a tough question. What does a typical day look like for you?

(laughing) Because the volume of what I need to get done in a day is so enormous, I’m super disciplined and there’s a routine to my day that helps center and move me along. It’s pretty much always the same day. I get up in the morning and preschedule some of my tweets and do very mild email. Then I head to the gym where I do my long-form reading on the iPad while on the elliptical. I come back, have breakfast, and start writing. I write three articles a day—usually two shorter ones and one longer—so I try to write the longer one in the first half of the day before things get too crazy. In the afternoon, I do more reading and preschedule the second half of my tweets. In the evening, I do yoga or meditation and then I usually have some sort of event or a one-on-one with a friend, which is my preferred mode of connecting. When I get home, sometime between 10pm and 1am, I write the remainder of what I haven’t finished.

That’s a very full day. Now for some lighter questions. Current album on repeat?

Sugaring Season, the new Beth Orton album, is amazing. This isn’t new anymore, but Love This Giant, the St. Vincent and David Byrne album has been on repeat for a long time. I’m also an enormous lover of covers. I’ve been on a kick of listening to covers of Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)” lately.

You probably don’t have time to TV or movies. Do you watch anything?

No.

Oh, this is going to be the toughest question I ask you. Do you have a favorite book?

I’m not answering that question. (laughing)

Do you have a favorite book from childhood?

I do, but that’s irrelevant because part of the beauty of intellectual life is that it’s ever evolving. To anchor yourself with such certainty to something like an all-time favorite is the opposite of progress.

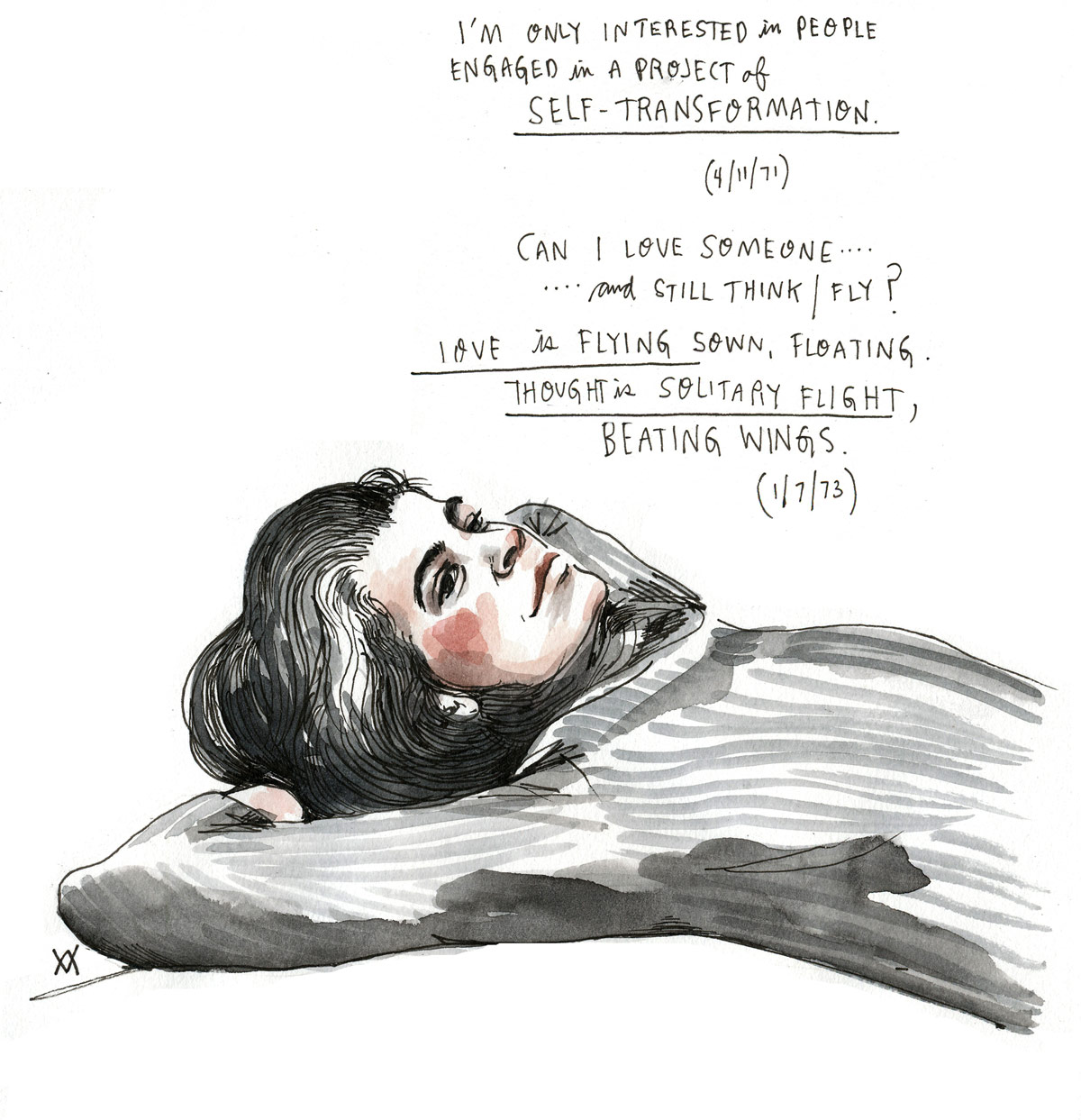

I will say this. I’ve been on a spree and really enjoying the diaries of Anaïs Nin and I know they’ll be a big part of my life forever. She started writing when she was 11 years old and wrote until she died. There are 16 volumes and I’m only up to the fifth one. The diaries are personal, but she writes them as a nonfiction narrator and they’re essentially philosophy and thoughts on creativity and life. She also meets all these historical figures and gives descriptions that get to the core of who that human being is. I am very moved by her writing.

Do you have a favorite food?

I eat the same things every single day. I wouldn’t call them favorites—it’s more of a functional thing. I do love all seafood except oysters.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I don’t really care about “legacy” per se. I want to be fulfilled while I’m living and when I die, it’s what people make of it. I would hope it’s something that’s meaningful to other people, but I also think legacy is caught up in all this ideology of afterlife and culturally, we spend too much time expecting the next moment to bring what this one is missing. That distracts from, to use Anaïs Nin’s term, “the art of living”. I don’t want to think about legacy; I want to think about doing things that are meaningful today and that’s plenty for me. Above all, I wholeheartedly believe Larkin put it best: “What will survive of us is love.”

“Don’t let other people’s ideas of success and good or meaningful work filter your perception of what you want to do. Listen to your heart and mind’s purpose…”