- Interview by Tina Essmaker November 12, 2013

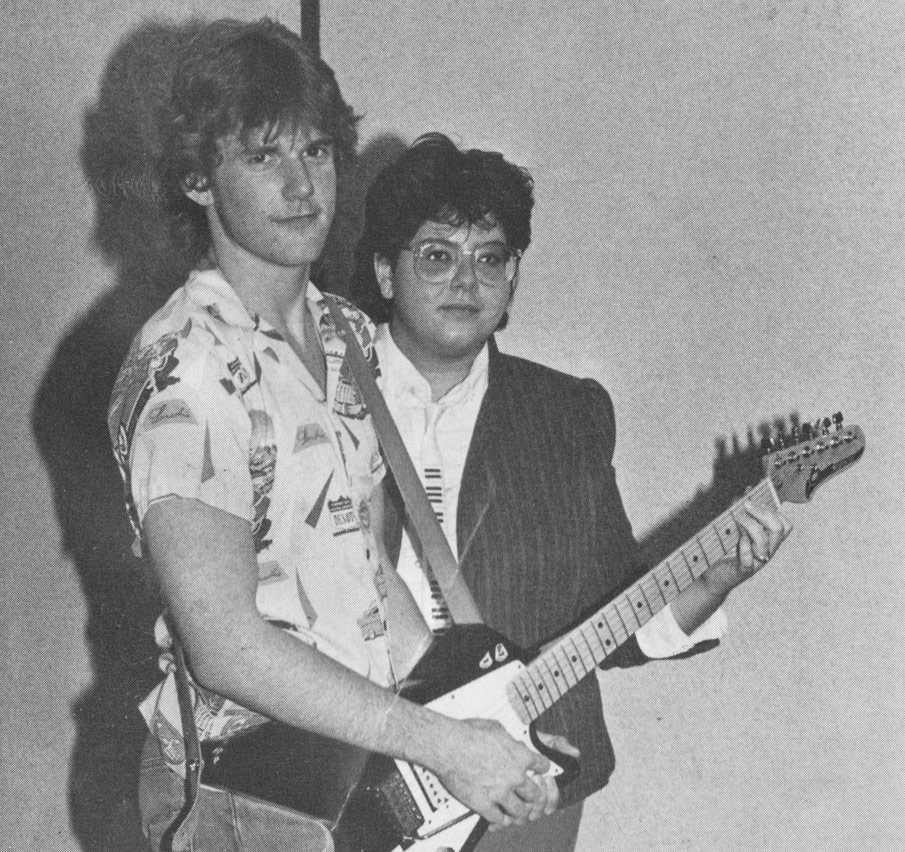

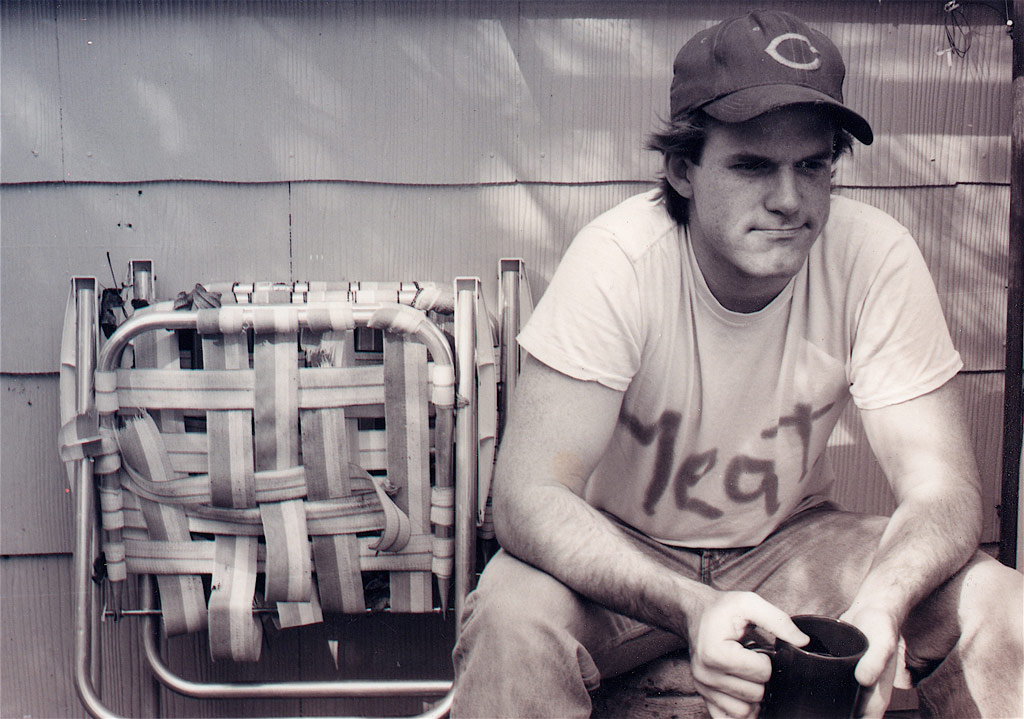

- Photo by Merlin Mann

Merlin Mann

- broadcaster

- entrepreneur

- writer

Merlin Mann is best known as the creator of 43folders.com, a popular website about finding the time and attention to do your best creative work. He is creator of The Merlin Show and cohosts You Look Nice Today, Back to Work, and Roderick on the Line. More recently, he has received rave reviews for his energetic productivity talks at Apple, Google, Adobe, and many others. Merlin lives in San Francisco, where the pork xiu mai is plentiful and his outstanding wife and daughter are within arm’s reach.

Interview

Describe the path to what you’re doing now.

I mostly do podcasts nowadays, and I like that medium a lot. They’re easier to make compared to other kinds of theoretical work, and I enjoy listening to them as well.

I started podcasting around the same time that I started a personal productivity website called 43 Folders in 2004.

Tina: That’s right. Ryan couldn’t join us, but he asked me to tell you that he was a huge fan of 43 Folders, which is where he first encountered your work. What led you to starting the site?

I started 43 Folders because I’ve always been interested in certain aspects of self-improvement, but also because I really needed the kind of advice that I ended up giving to other people. I’ve always felt like my personal productivity, or my ability to make the things I wanted to make, was out of reach. I wanted to be able to do that stuff, but somehow I wasn’t always able to get my hands around it.

While that can happen to people creatively, it was a problem for me professionally. In 2004, I was working as a project manager for web projects. I felt overwhelmed by the amount of information I had to deal with, and by the conflicting expectations of having very little control over what people wanted from me and being unable to get things done in a way I was happy with. I was constantly feeling stressed out, which is a feeling that goes all the way back to when I was a kid: I was always turning papers in late and starting the science fair project at 1am the night before. It was a natural fit for me to be a professional basket-case.

Speaking of being a kid, was creativity part of your childhood?

No, not really. I have funny, conflicting emotions about that because I’ve never been very ambitious, especially as a kid. I clearly recall the school year feeling like it lasted the equivalent of a decade. I couldn’t wait until the end of the day so I could go home, or the end of the school week so I could get to the weekend.

I did various pseudo-creative things, but my heart wasn’t really in them. I played various band instruments when I was a child, but that never really took. I wasn’t one of those savants who started playing Paganini at the age of four. I played guitar pretty poorly in high school, and I enjoyed listening to music and playing in bands until I moved to California in my early 30s. I guess music was my main creative outlet.

I find this to be such an intriguing question because, not too long ago, I met a woman at a speaking gig, and her kid was 17 and getting ready to do something after high school. I leave that deliberately amorphous, because she said something that really grabbed me: “There are two kinds of parents of seniors in high school: there is the kind whose kid knows exactly what they want to do, and it terrifies them; and then there is the kind whose kid has no idea what they want to do, and it terrifies them.”

So what did you do after high school?

If people want a Lego-block version of my life, I could say: “I was a child, then I went through elementary and high school, then I finished my 12 years of schooling, then I went to college, then I got a job, and then I got married.”

All of these things line up in a sensible way and make me seem like a normal person, but I never really knew what was coming next. When I look back on it now, all the fantastic ideas I had in high school about what I would do one day seem ludicrous. I thought I’d be a minister or an accountant or a professional musician; I didn’t have the experience or exposure to know any better.

I feel like I’ve always been surrounded by really supportive people who knew what I needed, even when I didn’t. People told me, “You’re going to this college. Go apply.” If I hadn’t done that, I’d have gone to the electronic school that was advertised on local TV. (laughing) But, it was never a foregone conclusion for me: college was a harrowing concept because there was no money for it and it always seemed very far away.

On the other hand, I’m really grateful for the school I ended up going to: it was unusual and exceedingly kind in accepting me, given my grades and background. It was an amazing experience, but I skipped through majors like a crazy person. In retrospect, it’s kind of chilling to think about what would have happened if I had committed to any of those. I feel fortunate that, (A) I didn’t die, and (B) I didn’t get painted into a corner where I had to become a doctor or a lawyer. I never would have had the chance to stumble into something interesting. There are a lot of people who know what they want to do at a young age, but they end up kind of hating it and becoming stuck because they’re successful at it.

I wish I could be more helpful and say, “You should find your dream path and paint a rainbow to your love cloud!” But, most of us are so stuck in this notion of how stuff should go that we want to find one of seven stories that matches our narrative. The fact is that most of us are wandering around, scared shitless, wondering what the fuck’s going to happen next. That’s as true when you’re 11 as it is when you’re in your 40s. It’s one reason that people feel very discouraged or disinclined to try new things—they feel like it’s not for them.

I understand that you’re asking me this because you’re trying to get the narrative, but my narrative is that I’ve never known what’s coming next—I still don’t. I fell down the right set of stairs and have been surrounded by people who have picked me up and said, “Let’s try this again.” It’s been one anxious block of uncertainty after another.

It’s interesting to hear you say that. We’re trying to give our readers a glimpse into people’s lives so they realize it’s okay if they don’t know what they want to do. It’s easy to look at someone who appears successful and think, “This person had a very direct path; they did steps A, B, and C to arrive there.” But that’s hardly the case with anyone we talk to.

Wow. I’m sorry you have to say that to people, because I don’t think there are that many of us who deliberately end up where we are for any reason.

It’s easy to start regarding yourself as some kind of big success, crowing about all the things you did to get there and how you became a serial entrepreneur. But, most of us are just lucky to be alive. We like to come up with stories about our lives that are sensible; stories that make us look good, like we’re survivors of adversity.

When we mythologize ourselves, we tend to amplify the things that turned out okay and try to turn the failures or lack of success into something we learned from. You can do anything to make your life look really grand. It’s a shame that so many people find it difficult to do the things they’d like to do because they feel cowed by seemingly successful people who appear to never do anything wrong, or always learn from their mistakes. That just rings as a lot of B.S. and self-mythology to me.

You mentioned having people who were supportive of you. Did you have any mentors along the way?

Oh, tons. The problem is that it’s hard to know who those people were at the time. It’s almost like some great, ineffable Kurt Vonnegut novel: it’s hard to understand the influence people have on you until 5 or 10 years later. It’s scary to think about what my life would have been like if they hadn’t been there.

Most of my mentors have been teachers: my first grade teacher, my drama teacher in high school, and a couple of my academic sponsors in college. At the time, it sounded like a lot of “blah, blah, blah,” so it took years for things they said to sink in. I feel like such a dope, because I got to a certain age and thought, “Oh my God, all those bromides that those dumb grown-ups wearing stupid pants told me were actually true.” I just didn’t have the ears to hear those impossibly true things. I think the only reason I’m alive is because of people like that.

Did you have any “aha” moments when you decided what you wanted to do?

I dunno. I always felt like people who consider themselves to be successful, creative go-getters want to go out and win a contest, make a comic book, or write a rock opera in high school.

I, on the other hand, gave up on stuff very easily. I had so little experience with a lot of the things I thought I wanted to do that when I started doing them and it didn’t come easily, or I didn’t get great acclaim for it, I gave up very quickly.

I think we sometimes overlook things we don’t realize we’re already good at or have limited experience with. You may be beating yourself up about not having good enough grades in biology to go to medical school while overlooking the fact that you’ve been working in your family’s hardware store over the summer for eight years and have an extraordinary sense of how to deal with people. That’s a skill that a lot of doctors in their 50s would kill for: they’ve never learned to understand and be empathetic towards others. People have all kinds of soft skills that you can’t train someone to have, but they beat themselves up because it’s not the thing they think they’re supposed to be good at.

Over the years, I’ve learned to be a little bit easier on myself while simultaneously trying to be more realistic about what I can actually do. I think a lot about do-ability with whatever silly project I want to do next. I don’t think about whether something is easy or not: I think about what trade-offs I have to accept in order to do it well, on time, and on budget.

I had a video podcast that I did for a while, and I loved doing it, but it was so much work. There was no revenue stream for something like that at the time, and the amount of production that went into doing an HD video podcast in 2007 was astonishing. It was a ridiculous amount of work for something that somebody only watched once.

On a positive note, I learned that I really liked the process of creating something like that. I also learned that I was trying to do things I had never done before: I was booking strangers as guests; I was learning how to set up a website; and I had to get all the technical help from my friend, Ben Durbin, who’s a bit of a genius.

It wasn’t as simple as saying, “I’m going to make a podcast.” It involved learning seven to nine different skills that I had varying degrees of familiarity with. It was great to learn that I loved doing podcasts, but I also learned to wait a minute and really walk through what it takes to do something like that. I looked at how much time it actually took, how sustainable it was, and what I had to give up in order to do it. In that case, it wasn’t tenable. Today, it might be easier, but that’s the kind of expertise and experience that’s really valuable.

It’s about doing something, even if it’s stupid, and getting through it as far as you can. It’s not about thinking that you’ll learn from your mistakes. It’s a matter of saying, “Here’s what I learned that I’m capable of that surprised me,” or, “Here’s what I learned I could do, but it takes a lot more time than I thought.” It’s weird: the things that seem easy can be so hard, and the things that seem difficult can be surprisingly enjoyable.

Is what you’re doing now something that you taught yourself to do?

Yeah. I think most people, if they are being honest with themselves, would realize they have a strange combination of curiosity and laziness. Like a lot of people, I can get really into something as long as it’s easy. It’s like Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s matrix of challenge level versus skill level: if you have high challenge and high skill, you get flow; if you have low challenge and low skill, you get apathy. It’s helpful to be mindful about what you’re doing and ask: “Am I doing the equivalent of stacking index cards for 15 hours a day? Or am I doing the equivalent of a Mandarin New York Times crossword puzzle that I have no business even trying?”

I do a podcast called Back to Work with Dan Benjamin, which is theoretically about personal productivity. All the production on that show is done by Dan’s team; I do stuff like writing show notes and bringing in sponsors, but that’s a turnkey operation for me.

The lesser-known podcast that I do is called Roderick on the Line, with my friend John Roderick of The Long Winters—he’s a writer and opinion-maker in that he will make your opinion for you. When we record that show, he and I will start talking around 6pm on Monday nights, then I hit stop an hour and a half later. I produce and upload it in 30 minutes, and I can come up with the show art while it’s bouncing down from GarageBand on my Mac.

In that case, I handle all of the production, but it’s totally doable. The small number of listeners we have really like our show, and it gives me so much joy to know that every week, I can help make something in two and a half hours that thousands of people will really enjoy. And I don’t have to pull my hair out doing it. Of course, over time I want to challenge myself to do new things.

I like to try and isolate what I’m most interested in getting better at. It can be very frustrating to keep sucking at something without realizing that it’s not the thing you should be trying to get better at. It’s like when our parents used to tell us as kids, “There is something that you don’t even realize you’re good at,” or, “People like you because of this, but you’re mad because it’s not this other thing.” Part of successfully growing up is letting go of unrealistic ideas that stop us from recognizing something else we’re good at and might enjoy more than what we’re doing now. There could be something 10 times greater than what you’re doing, but you don’t realize it because you’re fixated on the thing you feel like you should be doing.

“…most of us are so stuck in this notion of how stuff should go that we want to find one of seven stories that matches our narrative. The fact is that most of us are wandering around, scared shitless, wondering what the fuck’s going to happen next.”

That’s for sure. Was there a point in your life when you decided to take a risk to move forward?

Yeah, but I guess everything feels like a risk to me. Like a lot of people, I’m much more inclined to make a change when I don’t have any other choice. Maybe I’m unique in this regard, but there haven’t been that many times when I’ve had a big plan and thought, “I’ve realized that if I move to New York and become a performance artist, I could sell out this theater within three and a half months!”

There were times when I just fell backwards into a job opportunity, then had a momentary blink of non-stupidity to realize that it was something I could actually do.

Graduating from college was certainly a huge example of that. In 1991, my first jobby-job involved moving to a different part of the state, and it was a really big deal. There was a woman I had started dating seriously, and it felt very risky to leave that. They were going to pay me $22,000 a year, which seemed like a king’s ransom at the time, and I would get a private office with my own Mac—it was like a dream. Like the kind of thing that rich people get to do. And I did it. In retrospect, it turned out great.

When I talk to my friends or clients about this, there’s always this feeling of wishing or hoping that you’ll eventually arrive somewhere. But, I don’t know anybody who’s ever arrived anywhere. Everybody I know with half a brain is always a little bit nervous about how long they’re going to be okay doing what they’re doing.

How many people out there say, “Gosh, I wish I could own a house”? Everybody I know who owns houses are losing their minds trying to make their mortgage payment or they’re scared to death about having to replace the roof. Anybody who wants more money, a better job, or a bigger house is ultimately just wishing for a new set of anxieties. It can be a great set of anxieties, because that means growth, but there are trade-offs to everything.

Honestly, a lot of times, the biggest risk I’ve taken is not moving fast enough: sometimes the risky thing is to do nothing.

You don’t need to look any further than the very large industries that have suffered in the last 15 or 20 years as the digital age has obviated the unique characteristics of their business. The entertainment industry comes to mind. There was a long period of time when they were whistling past the graveyard, talking about having enough lawyers to sue their customers and giving away a lot of lead time to other businesses. A lot of these large corporations are still catching up to these small startups that figured out something they were reluctant to look at. In that case, their risk isn’t saying, “Why don’t we spend 5% of our budget on something outlandishly innovative?” Now they have to think, “We’re laying off a lot of people and making less of a profit than we used to.” They waited too long, hoping that everything would stay the same.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do? Do they understand it?

Yeah. I think so—I hope so. If they ever understand what it is that I do, I hope they can explain it to me. (laughing)

When I started 43 Folders, I was inspired by a lot of the blogs that I was reading in the years prior. I always have to mention reading Jason Kottke’s blog and Heather Champ’s photography site—those people were all rock stars to me. I wanted to be like them; I wanted to be admired like them. It sounds strange to say this now, but in 2004, the idea of having a blog that you could make money from was still not much more than a gamble. People could make a few bucks a month from their site, but it would probably be weird and inconsistent. My wife was extremely cool during that time. Even if she hasn’t always understood what I was doing, she has always been incredibly supportive and has trusted me with these things, which has been amazing.

Being in this kind of industry is hard sometimes, though. It used to be a funny joke, but now it’s a cliché because so many people suffer from it. As self-involved as I am, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what people think of me; I don’t Google myself. When you asked me for a photo, I had to visit my Wikipedia entry, and I mentally blocked out everything except the part with the picture. I don’t like reading or thinking about any of that.

During the holidays, I’ll go to a family dinner and see relatives I haven’t seen in a while. They will say something like, “I heard you’re doing stuff on the Internet, so I Googled you,” and I just think: “Oh, shit. Give me your phone. Put that away. Can we talk about the stuffing, please?”

Can we just be people here? (laughing)

Yeah! They say, “There are 200,000 people following you on Twitter and you…make dick jokes? I don’t understand,” and I’ll reply, “Yeah, I don’t really understand it either.” (laughing)

I’ve been fortunate in the sense that I do silly stuff that some people seem to like. I don’t like to bust a gut about it because I think it’s unseemly, but sometimes I feel like a 46-year-old Holden Caulfield. I don’t want to sound like a big phony by saying, “Oh, I’m so grateful that everybody is so nice about my work,” but I actually am!

If I were going to toot my own horn, I would say that I’ve been smarter than I used to be about trusting my own instincts and not being swayed too much about what strangers say. If enough strangers and friends say the same thing about what you should be doing differently, though, then it’s probably something you should listen to. Still.

I talk about awful and objectionable topics on You Look Nice Today; I say occasionally controversial things about how we work; and sometimes I get glares from executive vice presidents at a talk I’m giving when they hear me say, “The problem is not the email; the problem is the managers.” (laughing) That’s all stuff that I believe is worth getting the stink-eye for because the people who need to hear it may eventually hear it. If one person out of a thousand hears what I have to say, and it makes them reframe the way they see something, then that is a win for me.

“It can be very frustrating to keep sucking at something without realizing that it’s not the thing you should be trying to get better at…Part of successfully growing up is letting go of unrealistic ideas that stop us from recognizing something else we’re good at and might enjoy more than what we’re doing now.”

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

There is nothing bigger than myself. Sorry, that was a joke. (laughing) What does that question mean?

In general, do you feel a responsibility or desire, either personally or through your work, to contribute to something that feels greater than you?

I’m trying not to roll my eyes, because that sounds like the kind of question that people want to answer by saying, “Well, I already do,” and, “Of course I do!”

I do the best I can at everything, everyday, which is not always that great, but it’s what I’ve got. Are you talking about trying to help the world?

It’s open to interpretation. But we appreciate honesty, too, so if you say, “Nope, I don’t feel a responsibility or a desire at all,” then that’s totally cool.

The problem is that it’s one of those questions that sounds like that old joke: “Have you stopped beating your wife?” But instead, it’s phrased as: “Have you donated to a charity to stop people from beating their wives?”

I mean, yeah, I guess so. But, it takes so little effort today to look like you care about something, and I find that distressing. Our culture has become so cynical about a certain kind of otherness—I don’t want to get into it.

Yes, I do feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than myself, but I don’t have any projects that I can point to about that. (laughing)

Okay. (laughing)

Not to get all Catcher in the Rye again, but is there anybody who donates money or volunteers their time without writing a Facebook post about it?

There is so little dignity about how we care for other people. It almost feels like if we don’t get to collect a ribbon for what we do, then it’s not worth doing. Sometimes I feel like it’s really more about personal branding than it is about helping people.

If you want to really help people, then go out and help people. It’s like when people say, “Buy this pink yogurt, and a portion of the proceeds will go to charity!” Well, you know what’s really great? Donating directly to a good cause and having the entire portion go to charity—and you don’t have to act like you’re Gandhi because you bought a snack. Just go spend some money on something you care about, then shut up about it: that’s a dignified way to be an adult who helps people.

I totally appreciate that perspective. Moving on, are you creatively satisfied?

Kind of, but I’m not tortured or anything. I’ll put it this way: on days when I’m not satisfied creatively, at least I have the presence of mind to know that I don’t have anybody to blame but myself. It’s been years since I’ve made my uneasy peace with the fact that there will always be too much stuff to do and too many expectations from other people. A lot of us like to write that off and say things like, “Of course I could do the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon if I didn’t have this mean boss,” but that’s not really true. You can do whatever you want: you are the person driving your vehicle whether you like it or not.

Is there anything you’d like to do in the future?

There are things I haven’t done yet, and I’m frustrated about not doing more to start those things. Part of it is that once you get older and have a family to take care of, you have to find a way to make money from what you’re doing. There are a lot of things I do just for fun, like playing music, but there are only so many hours in the day for stuff like that.

Sometimes, my biggest frustration is not being able to take something I know I’m pretty good at and turn it into an ongoing thing because I either can’t find a revenue model for it or I literally don’t have time to do it well. I’d love to do more live shows and performances, but there’s a lot of overhead for traveling and booking theaters.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out?

Well. Whether I’ve met you or not—young person—my observation is that you are probably not as screwed up as you think you are. And even if you are screwed up, it’s time to start acting like you’re not.

Give yourself a little bit of a break and let yourself have some dignity. Hold your head up and act as though you’re capable of something better than what you have. There is so much negative self-talk that we do to keep ourselves feeling terrible about everything. Sometimes it can be helpful hearing a dork like me talk about this, but sometimes it can be helpful to talk about it with your friends and discover what horizons are out there that you may not even be aware of.

It’s about having a strange combination of high expectations for yourself, but for the things you’re capable of doing. It’s kind of unreasonable for you have high expectations about things that you have no business even trying, for example: “I’m mad at myself because I tried to run a marathon today and it didn’t work out.” There’s no reason to think that you would be able to do something that other people have spent years preparing for. It’s not realistic, yet you beat yourself up about it, so then you feel incapable of doing other things.

Go a little easier on yourself, and in so doing, be prepared to make and do things that might seem silly at first. Just keep moving: don’t ruminate and stare at the wall. Don’t just play with your phone: go out and produce something.

Also, take a walk and get out of the house. Just un-pot yourself a little bit. Put yourself into a different environment where you don’t have to be the person who feels bad about themselves.

“Go a little easier on yourself, and in so doing, be prepared to make and do things that might seem silly at first. Just keep moving: don’t ruminate and stare at the wall. Don’t just play with your phone: go out and produce something.”

That’s great advice for anyone, at any age. So you’re in San Francisco, right?

Yep.

Does living there influence you?

Very little. I say that while living here, but if I went and lived anyplace else, I’d be singing a different tune.

I have an office that is very near my home. Something that is completely perplexing to my single friends is that my wife and I both work, pick our daughter up from school four days a week, and then spend the afternoons with her. That’s my life. I don’t go out that much. God, people with kids are so annoying. (laughing)

These days, I’m the one who is perplexed when I see friends with two, three, or four kids go somewhere for a week. I just don’t know how they do it.

Are you saying that they take their kids with them or leave them with someone?

It’s for business, so they don’t take the kids. I don’t say that from a place of envy, however, when I travel somewhere for work, I’m racked with guilt the entire time because my wife’s schedule is totally disrupted. Maybe those people are wealthy or have a lot of family nearby or their world is big, but our world has had to get a little smaller to take care of family and be around for things like soccer and school.

I just don’t want my kid’s childhood to get away from me. I know that sounds corny, but I want to be there for my daughter.

When my wife and I found out that we were having a girl—and I hope this doesn’t sound sexist or anything—the women I talked to all said the same thing: “Never be afraid to hug your daughter.” They told me to hug her so much more than I think I should. It might seem weird, but no little girl says, “My dad hugged me too much.”

Get down on the floor and play with your kid way more than you think you should, because eventually it’s going to go away, and there isn’t anybody out there who wishes they had less of that.

My daughter and I are really into the card game UNO, and sometimes I’ll be sitting alone in some fucking hotel room, staring at The Dog Whisperer, and thinking, “Man, I wish I could be at home playing UNO with Ellie right now.”

I’m sorry. This is so corny!

No, it’s awesome!

Well, I’m not trying to imply that I’m some super-dad, because I’m not. I’m completely racked with this feeling that there are a thousand things that I could always be doing better.

Living in San Francisco is great, though. The elementary school that my daughter goes to is fantastic; I like where we live; I like our house. I like a lot of it. But, it’s not like I’m sipping mojitos, looking at sculptures, or going to parties for startups.

When I go to those things these days, it just makes me feel dead inside. Maybe it’s just because I’m old? I used to feel energized by that stuff, but now it just feels like a costly circle-jerk.

Sometimes the most inspiring things about San Francisco are not the fancy white people and their startups. Instead, it’s walking around the city and seeing how people live their lives in this crazy town; it’s being around a whole mix of different kinds of people that is really inspiring, and I’m really glad my daughter has exposure to that. I would miss San Francisco terribly if we moved, but there are times when I think—(laughing)—that it’s a rich, young person’s town in a lot of ways.

Where do you live?

Ryan and I are in New York, but we both grew up in Michigan. We actually haven’t been to San Francisco, but it looks beautiful.

Oh, don’t get me wrong—you should definitely come here! I just feel the need to speak up against the whole idea that there’s something magical that happens here.

A lot of people think that if you come to San Francisco, then you suddenly become successful and smart and tall and slender. It’s just not true. We talked about this in the very first episode of Back to Work, because my friend Dan is fond of—and I can never tell if he’s being serious or not—making jokes about how fancy San Francisco is. He’ll say things like, “You get to hang out with Ev Williams!” And you do, but then what? What are you going to do differently after you’ve met the celebrity or gone to the fancy party? Is that proximity going to make you better at what you do? Maybe, but not necessarily.

I’m originally from Ohio, and I’m a terrible Buddhist in every conceivable way, but I do believe that we sometimes don’t notice things until they change. When I travel somewhere, I’ll sit in my noisy hotel room that probably has bed bugs and whine, “America has turned into nothing but six-lane highways!” It’s so dispiriting and commoditized and packaged. (laughing)

When I come home to San Francisco, I think, “Oh my God, this is so much nicer.” We live in the top 10% of walkable neighborhoods, so we walk everywhere. We walk to the grocery store and my daughter’s school, and we’re near public transit, so we don’t really need a car.

The funny part is that I know I’m blessed with those things. When I whine about San Francisco, it’s about there being a kind of passionate demand that people get as worked up about stuff as everybody else is. Part of what makes the town great is that people are passionate about whatever those issues are, but sometimes it’s a little squirrely. I start to feel a little bit fatigued by the amount of enthusiasm for something I’m supposed to care intensely about for 36 hours. There are things I care about, but I don’t like feeling as though I’m not participating in the body politic if I’m not angry most of the time.

Otherwise, you should totally come visit San Francisco! Please indicate at this point that I am being legitimately enthusiastic. It’s a very nice place.

I actually have a friend from high school who has been out there for years, begging me to come visit. I’m sure we’ll visit at some point.

Something I think about a lot is the idea that whenever we travel somewhere, we like to think we become someone new. That when we arrive somewhere, whether that’s San Francisco, New York City, or somewhere for a vacation, we’re going to show up and become different just because of this new proximity. The old you is always in the suitcase, and wherever you go, there will still be an old you there. Old Florida/white-trash me is always going to be wondering where I can find a Subway sandwich because the menu here is confusing. The largest part of me is the part that has been with me my entire life, so the part that has been with me for two days in this new location doesn’t really mean anything.

People aren’t transformed by locations, unless they’re a fruity artist. If we’re honest with ourselves, most of us are looking through the lens of the life we’ve always had, and from a distance, it looks transformative. San Francisco and New York look like the land of Oz or Disney World, but when we arrive there, we still have to go do stuff; we still have to show up on time for things. There are constraints to all of those places that we don’t see until we get a little bit closer.

Eventually, we find a place that feels like home and learn to love it, but there’s no place where someone just waves a magic wand to make us become the people we want to be.

I totally agree. Ryan and I were married and had been living in Michigan for about six years before we came to New York City, but everything we’re doing now started in Michigan. We didn’t have a creative community around us there; we were working day jobs and wanted to do something creative together. We had the realization that if we wanted to do something, we needed to do it, no matter where we lived. Some might think we’re living a fabulous New York City, but we still get up, go to work, go home, eat dinner, and work a little bit more. It’s a very similar schedule to what we had in Michigan.

I assume you have an apartment. How many square feet?

Our first apartment was 400 square feet. (laughing)

That’s the size of my office, and my office is small. (laughing)

It was tiny. Our current apartment is almost twice the size of our old one, and it feels like a palace! (laughing)

We have a flat, which is just San Francisco-speak for an apartment that takes up the floor of a building, and it’s just south of 1,000 square feet. People who come come out to our far-flung neighborhood from the central parts of San Francisco say, “Wow, this place is a palace.” It’s like the country mouse and the city mouse: my friends in more rural areas talk about “fancy” San Francisco, and I say, “But you have a yard, and your mortgage payment is half my rent.” They own a house! At this point, unless something really extraordinary happens, I’ll never own a house. Compared to the guys who are smart and planning for a big grown-up life, I’m like an advanced college student. (laughing)

“People aren’t transformed by locations…Eventually, we find a place that feels like home and learn to love it, but there’s no place where someone just waves a magic wand to make us become the people we want to be.”

What does a typical day look like for you?

I get up and hang out with the family, depending on whether it’s my day to drop off our daughter. After that, I’ll go to the office and write or record podcasts. Then I’ll read and listen to a lot of music and podcasts.

It’s hard to say what a typical day looks like because I have different schedules depending on what I’m doing. For instance, yesterday I watched When Harry Met Sally and drank iced tea.

If I’m writing, I like to get up and write really early. If I’m futzing around with podcasts, I’m not really on a schedule apart from the times I have to be somewhere to visit with somebody. I usually check my PO box and try to get my steps in on the FitBit. (laughing) Pretty sexy stuff.

It’s the truth, though. Most of the people we interview say their days are routine, but that’s part of doing the work.

I don’t want to get too much into my productivity racket stuff, but there are things people can do to improve how their days go.

For the reasons I’ve already stated—but also because I have a family and I’m lazy—I’m pretty conservative about what I agree to do with people. My former life as a project manager taught me that very few projects turn out the way we expect.

Everything takes more time than you thought, everything costs more money than you thought, and almost everything turns out not quite as cool as you expected. Sometimes it happens differently, but when you’re working with other people on a team, and you only have control over one aspect of a project, things rarely turn out as cool as you would hope.

So true.

That’s just the reality of being a person who makes stuff. It’s one reason why I like to keep such tight creative control over what I do: if it sucks, at least I can take credit for it sucking.

For example—and this sounds really uncharitable—I agreed to have a call with you that was easy to schedule. But it’s not unusual for somebody to write me and ask if they can have a call with me. Then I have to write back and ask what they want to have a call about. Then they write back, saying, “I’d like to talk to you about some business opportunities.” Sigh. “Okay,” I write back—in the fourth email at this point—“What is it that you want to do?” Then they send me an email saying something like, “We’re looking to extend our vertical by doing a deep-dive, opening the kimono, blah, blah, blah,” and I just think, ugh.

What does that even mean?

The old me would have kept talking to that person, but now the newer me says, “I’m sorry, I just can’t do this right now.” If I said yes, then we’d have to schedule a call, which takes at least two email exchanges: will it be Skype, will it be on the phone, what time can we do it? Then about 30% of the time, the medium and/or schedule changes, so we have to exchange emails about that. It’s not unusual at all—and I have clocked this, my friend—to spend over an hour to find out that you’re going to have a phone call with somebody that is completely pointless.

It makes me sound fancy, but I sometimes wonder if the reason some people find it so hard to get anything accomplished is because they haven’t gotten picky enough about their time. I like having a big block of time where I don’t have to do anything. So, what do I do instead—schedule five calls with people I don’t know to talk about things I don’t want to do? That’s not a life; that’s a way to behave if you want to be a crazy, distracted person.

A lot of the best work I’ve ever done started out as something completely different because I gave myself permission to have space around my time and expectations. It’s about being open to the idea that I’m the fucking pilot of this jet; I’m the one who has to decide all the stuff that happens in the Merlin Mann Enterprise. The more I accept that and build the relationships I want to have in order to make that work, the better off I am. It’s when I abdicate the power for that and start blaming the world for why things are the way they are that life goes tits-up.

My best success comes when I trust my own intuition of being capable of doing something cool, then put all of the things I need to get it accomplished in place. That could mean not answering the phone, or it could mean saying, “I didn’t have time to read, let alone answer your email.” We are constantly faced with impossible things, and we have to accept that some things have to stay impossible if we want to produce anything of value.

It’s so tough with social media now, because everyone feels like everyone else should be accessible to them all the time. If you don’t respond to a message on Facebook or Twitter, you feel like an asshole. I would literally be writing emails all day if I sat down and wrote out a thoughtful response to everyone. It’s not possible. We need to realize that we’re not victims. We can take control of our days and schedules to focus on what’s really important.

You’re absolutely right. I think that’s a very healthy way to look at it. But, let’s say the difficult thing: if somebody writes you an email, you’re going to write them back. What’s going to happen after you write them back?

They’re going to write me back. (laughing)

Exactly. Now what do you do? One message that started out as just a polite response turns into four or six or eight emails. Now you’ve created the expectation that you’re going to be having an email relationship with that person. If you can handle that, it’s okay. But I don’t know how to have that conversation with every stranger in the universe.

The way I once phrased it on 43 Folders was: every time you communicate with somebody, you’re handing them a pebble. That pebble seems impossibly small to you because you’re the most important person in the world, but you have no idea how many other pebbles that person was given today. What if you made that person completely lose hope because you sent them four pebbles in the last week and it’s unsustainable for them? I’m as selfish as anybody when I think, “Why isn’t this person writing me back? Why hasn’t this person responded to my tweet?” We all do that, and it’s because we all think we’re the most important thing in the world.

A compliment shouldn’t come with a request. I remember standing at a urinal in a bathroom next to Tom Hulce in the late 80s. I turned to him and said the same thing I’ve said to every celebrity I’ve ever met: “I enjoy your work.” He said thank you, and then I walked away. (laughing) I once ran into Jeffrey Jones—the guy from Deadwood and Ferris Bueller—on the street in San Francisco. I said the same thing: “I really enjoy your work.” Again: he said, “Thank you,” and I walked away. I’m guessing that’s exactly the amount of interaction that Jeffrey Jones wants to have with somebody. He wants to be appreciated, but he doesn’t want me to ask, “Hey, do you want to go get a drink?” (laughing) because then he’d be a dick for saying no.

We get some really thoughtful emails from readers who specifically write: “You don’t have to respond to this, but I just wanted to say thank you.” I always appreciate that because they’re respecting our time and we don’t feel like jerks if we don’t have the time to respond.

Oh, yeah. When I get a reply on Twitter from somebody who says, “I really appreciate your work,” or, “You did something five years ago that meant a lot to me,” I am very, very likely to say, “Thank you,” or, “That made my day.” That’s the perfect amount of interaction. When I see people constantly give out their email address, I think, “You’re going to regret that someday.” (laughing) I just think that’s unsustainable.

“A lot of the best work I’ve ever done started out as something completely different because I gave myself permission to have space around my time and expectations…”

That’s a good point. So, what music are you listening to right now?

I’ve been going through a phase where I listen to a lot of music that my daughter likes.

I do still listen to a lot of 80s and 90s indie rock to the point where it’s almost a disability: I’ll hear some new band, and it just makes me want to go listen to an older band. I still listen to a lot of the bands I liked in college, like Guided By Voices, Dinosaur Jr., and the Pixies. I’ll go through phases of my favorite bands, like listening to Reckoning by REM for a week straight. I also love the New Jersey band, The Wrens. They’re one of the best bands ever. I also love John Roderick’s band, The Long Winters. In the last three or four years, I’ve really gotten in the the Foo Fighters, especially their The Colour and the Shape record.

Also, I’m just not exposed to as much new music anymore. Sometimes it seems like there’s some British or Scottish band who are all the rage at a given time that I’ll be into for a week, but they will have absolutely no longevity, so I go straight back to Dinosaur Jr.’s You’re Living All Over Me.

I do a similar thing. Ryan is constantly listening to new music, but I feel bombarded by it. When I can’t take anything else in, I go back to Patty Griffin because I know that she can write a damn good song and I like her style.

Yeah! Somebody once told me—I don’t know if this is true, but it should be—that when you see people in their 60s or 70s with really weird hair, it’s because most people tend to keep whatever hairstyle they were wearing from the time they were happiest in life. So when you see an old lady wearing a beehive, it’s because it’s from a time when she was most happy.

I think that’s true about music as well. There is a period from 1986 to 1996 where it’s impossible to articulate the impact that new music had on my life. There was so much stuff coming out during that time that I was obsessed with, like the Dead Kennedys and the Breeders. It isn’t as simple as saying that’s when I was happiest, but it was a time when music had an emotional impact on me. When I was putting up the 43 Folders site, I had The Meadowlands by The Wrens on repeat for over a week and it became like a good friend.

I can definitely relate. Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

Yeah, tons. I really like Edgar Wright movies right now. He’s the guy who did the Cornetto trilogy with Nick Frost and Simon Pegg. He directed Shaun of the Dead, Hot Fuzz, and The World’s End. The World’s End, which is a movie that came out this summer, is already one of my all-time favorite movies. I also liked Pacific Rim.

This age of binge-watching makes it easier now to dig all this stuff up. Edgar Wright and much of that same team also had a two-season TV show in the late 90s called Spaced. It’s on Netflix, and I highly recommend it.

I watched Wicker Man last night—that old, crazy British movie from ‘73—and all I see is Edgar Wright all over that thing. I love his ongoing theme of a schlub in a strange place that becomes weirdly supernatural.

For TV shows, I’m kind of into Homeland right now. The latest episode was probably the best episode I’ve seen. It’s not even the kind of show I normally get into: it’s more of my wife’s thing. I also love Adventure Time!

We love Adventure Time as well!

My daughter and I love that show. I’m also really into WWII and Holocaust movies. I find them endlessly engrossing, fascinating, and terrifying.

Any favorite books?

Mmmm. I honestly don’t read many booky-books much anymore, although I was quite a reader in college. I’m inclined to say Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, and A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole, which is one of the greatest books ever written—it’s also where I got my Twitter username, @hotdogsladies, from.

I read a lot of news articles and long features on my iPad, and I read a lot of comic books these days. My two favorite comics are Hawkeye by Matt Fraction and David Aja, and Saga by Brian K. Vaughan. They’re both really good.

What is your favorite food?

A rare rib-eye steak and tri-tip. I make the shit out of some tri-tip. It’s perfect: it’s not expensive; just use kosher salt and pop it in and roast it. So good.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I’ve tried to figure that out, but I don’t really know. I don’t think about it a lot because it scares me. Legacies are what people tend to think about when they realize they’re about to die, so I probably won’t start thinking about it until I get to that point.

I can’t think of anything to say that isn’t a cliché. I hope people will read things I’ve written and be occasionally surprised that’s it’s still useful. I hope people can look at one of my bust-a-gut essays and get something out of it that makes their week a little better, or makes them look at their life a little differently. That would make me happy—but I’ll be dead, so it won’t matter. (laughing)

Yeah, that’s a tough question.

It’s such a paradoxical question. Your legacy is not going to matter when you’re dead. When you’re dead, who cares? You’re gone. A person wants to have a legacy because, as their life drifts away, they can know that people will like them. It’s consolation for the last moments of life: that’s what legacy really means.

That is a serious question. (laughing)

I’m going to go cry and eat bon-bons now. (laughing)

Steak and bon-bons.