- Interview by Hugh Weber March 24, 2020

- Photography by Chynna Lockett

Micheal Two Bulls

- artist

- musician

Micheal Two Bulls is an Oglala Lakota artist from South Dakota whose work spans an eclectic array of disciplines and mediums. Two Bulls weaves together elements of photography, drawing, painting, printmaking, songwriting, and other creative disciplines to create multi-layered compositions that invite his audiences to question and explore. At the heart of his creative process is a unyielding commitment to collaboration, community, and family. This commitment is reflected in the nature of this interview, which includes Douglas and Reed Two Bulls, family members who feature in many of his creative projects, including The Wake Singers band.

I found this description of your work and it says, “Micheal Two Bulls is a third generation Oglala Lakota multimedia artist who is notable for his multi-layered compositions incorporating digital work, photography, drawing, painting and a variety of printmaking methods.” How does that sit with you?

Micheal: I dabble in a lot of different things. I mean, for me, creating art, I don’t box myself into one subject, like, “Hey, I’m just a painter. I’m just a printmaker.” In reality, artists are working on all these platforms constantly, but they’re all just tools we use to say something.

Ok, let’s start at the beginning. Tell me a little bit about where you grew up and what that context was like.

Micheal: I grew up in Rapid City, South Dakota in my grandfather’s house. But my grandfather is originally from Red Shirt Table on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. I spent a lot of my childhood there, too. So it was like this back and forth of being in Rapid City, but also being in Red Shirt Table. To look back now, it’s definitely interesting and unique.

Those were two wholly different contexts, but they’re geographically close. How did bridging those places shape your understanding of yourself and the way you think about creativity?

Micheal: Well, I think a lot of it had to do with growing up around artists, watching my uncles, my aunts and grandfathers making art with their hands and selling it and talking about it. At an early age, that was our bread and butter. My mother put food on the table with her beadwork. I had a grandfather, Eddie Two Bulls, who was a very well-known painter. He did that for his living in order to feed his whole family. And seeing that in both Rapid City and in Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, I can see the influence that moved me in a way to the work I’m making now.

I grew up listening to stories about Red Shirt Table from my grandfather. He grew up there with the big Two Bulls family, which is a huge family.

And Red Shirt Table is very rural. I don’t know if you’re familiar with The Badlands of South Dakota National Park. “The Table” is just above the south unit of the Badlands. It’s beautiful. Not many people even know about that place today, which also makes it very special.

Going down there as children we’d play, explore, and learn that history—which is very complicated. During World War 2, the air force would do a lot of B-17 practice bombings there. As children, we would find old 50 cal cases, doors, hatches—a B-17 actually crashed down there. So it was always a treasure to go down and find these things. But, as we got older, we realized that history was pretty dark because it displaced a lot of family members that lived there. They had to move out because they’d hear something like, “You’ve got so many days before we’re gonna bomb this place for target practice.” That place is so packed-full of dark things in that way. As a child, taking those hikes or whatever, it was a very different mindset. Looking back now it’s like, “Man what was going on?” Then you take that contrast to Rapid City where you’re growing up in the public school system where there are maybe four native people in the whole school and you think about what kind of impact that has on you as well. It’s a very stark contrast.

Is there anything about that contrast that shows up in your work?

Micheal: Oh yeah, easily. For about five years I went back home and I worked with a lot of the elementary schools in Rapid City. That was a profound experience because I could see myself in the Lakota children that were there. I was the only native person working at this school of maybe 80 percent native children, and that was mind-boggling for me. But I tried to take all of this baggage and trauma from school and create something. I’m working here now with these kids and I’m asking myself, “How do I navigate this with them, knowing this is also my history?”

That’s got to be catalytic as a young creative or as a young human being. You said trauma, but that’s a jarring juxtaposition —

Micheal: —I use the word trauma because as a young person growing up around that, that’s what it really was. You could even make a broader statement saying it’s historical trauma. It’s what my ancestors went through. It’s something that I know a lot of natives struggle with. A lot of my family members struggle with it too. But also, it catapulted us to say, “Okay, we know we’ve been through this, so how do we deal with it now? What’s the solution? Is there even a solution? How can we move forward from this?” And I think that’s the position I try to take in my life now.

You create with so many members of your family. Can you tell me what it’s like to collaborate when collaboration is so deeply embedded in your family and your friendships or that extended family concept of tiospaye?1

Micheal: Well, I only speak of it because collaboration is a passion for me. I love collaborating with people. The more the merrier for me, even though sometimes it gets a little complicated and crazy. But I love navigating that sense of community musically and artistically. I try to create spaces where that can happen, like this time last year when we created a family show that dug into [stories and content] that pre-date the third and fourth generations of our family.

I was reading a number of articles that have been done on your collective work over the last several years, and you were quoted as saying the following:

“For native artists on the reservation, there is no other income. You have to create your own jobs. Art is how my relatives make a living. And to have an organization promoting livelihood is important for community and culture.”

So often in our society and especially in this region at large—native or not—people are discouraged from creative work because they’re told it doesn’t pay. Your family seems to have modeled something different in that way. What did you learn from your family about how to find that balance between artistic passion and also paying the bills and putting food on the table?

Micheal: Jeez, that’s a tough question because when we first started to curate this family show, I didn’t want to disrespect a lot of the other families by saying, “Oh, the Two Bulls family is the premier arts family,” when that’s exactly what a lot of families on the reservation are doing. I would say maybe 70 percent of the families in Pine Ridge are making something to make a living. It is one of the poorest counties in the nation, so a lot of it is basic economics. I mean, what do you do when there’s no jobs to survive? You’ve got to make art. And in the Black Hills area—West River—it’s a very tourist-centric place. So, they go hand-in-hand.

How do you deal with those tensions? You have a unique, singular voice from your experience and your family’s experience, but it’s not what necessarily sits in the galleries in Rapid City.

Micheal: That is a very loaded question for me. It’s the same question I’ve been answering since the first year I went to art school many, many years ago. Doug and I both went to the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. So it’s not just our community that’s dealing with that, all of these different pockets and reservations across the nation deal with that same idea. But what I found during those years is that our generation and the generation that is coming after us are exploring and challenging that idea. We’re saying, “Okay, we don’t have to make this tourist art anymore.”

That’s not to disrespect those who make that kind of art, it’s just that we’re looking more inward now, like, “Okay, well, we’ve done that since the train went through Santa Fe for the first time.” I think now, a lot of these newer native artists are challenging that idea—asking, “What is native art? Is it native art or is it just art? Is it contemporary art?” I try to stay away from those sorts of labels and just do it. I just show the work. Action speaks more than these academic terminologies.

“That’s not to disrespect those who make that kind of art, it’s just that we’re looking more inward now, like, ‘Okay, well, we’ve done that since the train went through Santa Fe for the first time.’ I think now, a lot of these newer native artists are challenging that idea—asking, ‘What is native art? Is it native art or is it just art? Is it contemporary art?’ I try to stay away from those sorts of labels and just do it. I just show the work. Action speaks more than these academic terminologies.” /Micheal

Douglas: The Native artists in the 60’s and 70’s opened that door, and it’s still being discussed. I mean, even as we speak, it’s probably being talked about at our old art school.

It’s not a new discussion. But it’s part of the story you’re stepping into and living into.

Douglas: And that’s something they’re confronting. The up-and-coming native artists, 18 and 19 year-olds, are being confronted with it.

Micheal: And I think it’s interesting because like I said, that’s how my mother put food on the table. It was that sort of artwork—that’s how we got clothes on our backs and stuff. But yeah, I think a lot of our generation went to art school and studied these guys in the 60’s and what they’ve done and what they produced.

So let’s talk a little bit about the work. Out of all the music, printmaking, and other installations you’ve created, what stands out to you as the most important. Why does it stick out?

Micheal: I’m super proud of a lot of the collaborations I’ve done with other people, one of them being my cousins. That’s the kind of work that I enjoy. The Wake Singers are our band and we collectively write, record, and produce all of our own music. We’re just now starting to perform again live, so that’s a new adventure.

And you’re prolific. I mean, I follow you on SoundCloud. I feel like you’re writing and producing a lot of music.

Micheal: I love doing it because it’s fun. But funny enough, the Wake Singers have been around for a long time in different forms. And we’ve always called ourselves an art band, which means we were always doing these artsy things. Even when we first started performing, we’d be at art galleries and art openings. Early on [our work] was tied to visual arts. That’s what I loved about the Wake Singers. Even now, I think we’re really tied to the visual world in a way.

What is the origin story of the Wake Singers?

Reed: I joined the Wake Singers in 2015. When I was 15, I recorded my first song ever with them. I wanted to get into music for a long time and it was cool to watch my cousins growing up, making music, making art. That always inspired me. So it was a big deal to me to be able to join them on that journey.

And now we’re actually a band and I’m the singer. It’s crazy. I remember being a little kid and hearing about the Wake Singers and now I’m part of that.

It becomes an ongoing, evolving family tradition.

Reed: The Wake Singers will never end.

Tell me a little bit about how that flow—the idea of music inspiring printmaking and visual arts inspiring music—has played itself out with the Wake Singers and in your work.

Micheal: I’ve actually thought about this a lot because my cousin and I always talk about it for some reason. Like, what’s the relationship between this visual work and this sonic work? I used to say that there was a separation, but through the years I’ve realized that they’re pretty much the same. As far as producing the work, like actually recording it, you’re layering all these things on top of each other. Sometimes it works, but technical things like that are very similar to printmaking or something like painting. All these layers are happening and sometimes you have to erase something.

But as far as an art band, Doug and I grew up loving bands like the Velvet Underground who were famously tied to pop art, or even like Robert Rauschenberg, who dabbled in a lot of performance art and music just to name a couple. We’re also big fans of Talking Heads. Those guys came out of our school doing these sorts of performances and video work as well. So definitely those “art bands” have had a profound impact on us.

Douglas: Well, we’ve been doing this since we were 15. We all started playing music early on, and then we got to art school and there was nothing to do on the weekends. You’d finish your work and it’s like, “Oh we’ll just sit down and play some music with people.” Then it would be the two of us left at the end of the day, because everyone else would be like, “I don’t know.”—

Micheal: We’d chase everyone away. [Laughing]

Douglas: No no, we’d just be like, “Well then we’re going to go back to making paintings.”

Micheal: The only thing we know how to do.

Douglas: “That was fun, guys, but we’re going to make pottery now.”

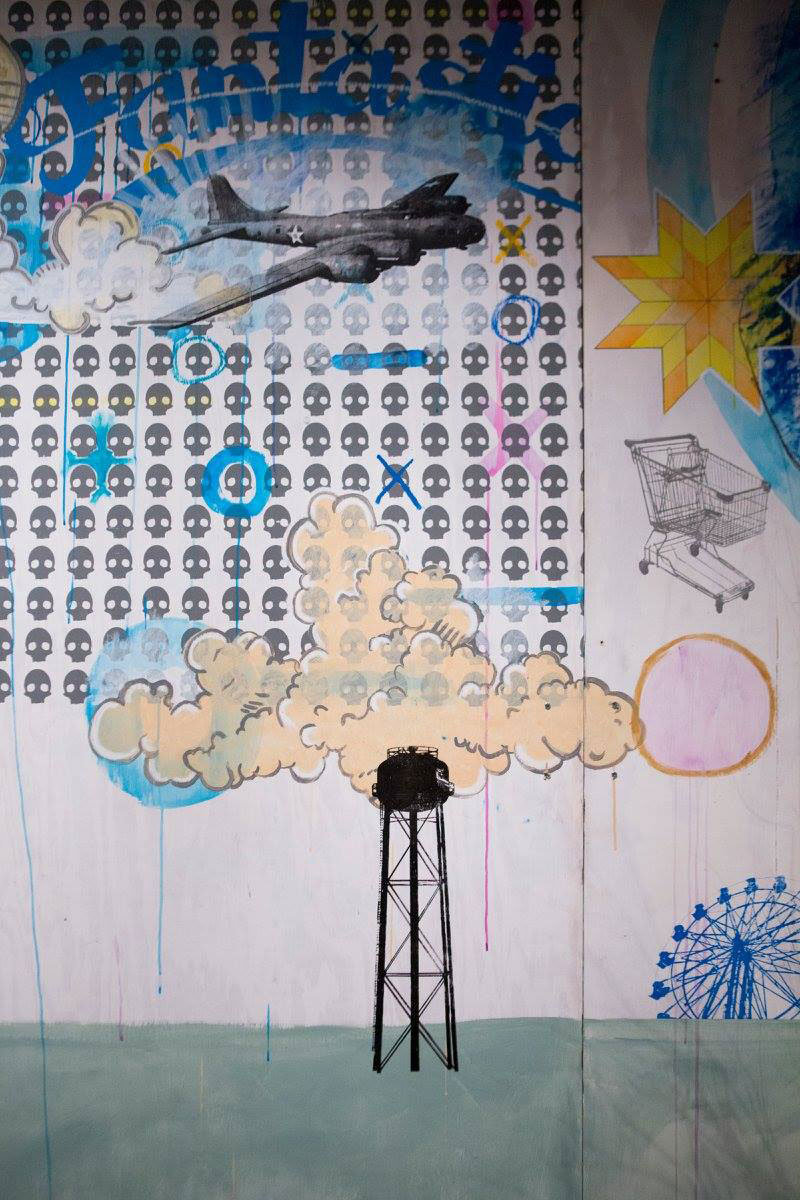

When I think of your work, I think of these layers. It’s the way you describe The Wake Singers’ music, but also the art. What’s interesting to me is that you have these heavy things like suicide, the Wounded Knee massacre, and deaths in the family sitting side-by-side with shopping carts and Ferris wheels and water towers.

Can you tell me a little bit about how those juxtapositions and layers inform the process or grow out of the process?

Micheal: When you read about these things in public school, there’s this subtleness, this tragedy—this tragic American history. It’s almost colorful. It’s there playing. And I think that informed a lot of my visual work where it’s like, “Oh, here’s all these bright colors and all these crazy compositions with these layers and colors happening.” It looks so fun, but when you dig into it, it’s all these bombers, or like the Wounded Knee massacre—those sort of layers that we all live within and [inherited] from our ancestors. A lot of it’s spontaneous. I’ll have a loose sketch, but when I really dig into it—when I lay an image down or a color—I react to it. You start having all these reactions and it starts becoming craziness. Chaos.

An element of your work that always inspires me is this compression of time. The idea that you can juxtapose a turn of the century elder with a 1950’s bomber and something very contemporary. Do you think that’s informed by the context of your upbringing or culture?

Micheal: Growing up, we hear these old stories from our grandparents and parents about these great things that happened. For me, that was Lakota history or Northern Cheyenne history, but you’re also living and hearing these stories about yourself —witnessing things in the present moment.

Recently, I traveled to the University of Washington, and there was an academic there that was asking those questions. Like, “So, what you’re basically doing is grabbing this old turn-of-the-century image and comparing it to modern technology?” But it’s not so simple. You can write about it. It’s easy. But once you’re actually living it or know somebody that’s lived it, it’s very different—not to say that my work’s not open for interpretation or anything.

Maybe they’re trying to flatten the layers or simplify the interconnections that are familial and cultural, and also like you said, “spontaneous.”

Micheal: Yeah, exactly.

Douglas: I was with Mike in Nebraska and he was talking about these concepts of 20th century, 19th century, 21st century things on reservation and city life. People walked out. When he started talking about what happened to the native peoples in North America there were young guys that were just like, “I don’t wanna hear this.” But the way Mike explained with the bombers and stuff, this is a modern day thing. People are living this way. People are living with all this baggage. There are people that want to hear it.

I did an interview a couple of years ago with Mary Bordeaux, and she said something like, “The act of being native in the United States today is a political act.” Inherently, it’s going to be controversial, even if you’re not saying anything of controversy.

Micheal: I mean, Diego Rivera said something like, “All art is political.” And when I read that, it always stuck with me. That even segues into something like the American consciousness. When they think of Native America, they think of these mascots.

Douglas: Drunks.

Micheal: Not only this romantic idea of Native America, like a warrior on a horse, but also these completely racist mascots that are [seen as being] completely fine. And it’s damaging. It’s damaging to a lot of native peoples. It’s a tough thing to navigate.

Can you tell me more about how ideas come to you? Whether it’s writing a song or it’s creating a more tangible piece, where do those ideas come from? How do they form?

Micheal: I’m always thinking. I think that’s the hard part for me. My head is always thinking, “OK, what can the next series be about or what do I want to say? How do I want to say it?” It’s very simple. In my sketchbook or notebook I’m always writing quick notes, like a phrase or something I see. It’s all this stream of consciousness in my notebook. And then from there, I start sketching ideas. I start loosely planning it.

That’s how I do a lot of my series. For example, now I’m working on an IHS series—Indian Health Service, the hospital, Sioux San, and Rapid City. There’s a lot of controversy that’s happening there right now. It got me thinking. I basically grew up going to this hospital. What were my experiences or my relatives’ experiences? So it starts with something simple like that—random quick phrases or sketches, collecting old photographs from when it was a sanatorium.

Two years ago I worked on the Wounded Knee piece and at the end of that body of work I was mentally exhausted. It did a number on me.

My good friend, Dr. Craig Howe, curates these shows like once a year now and I’m very involved in them. About two years ago, he did one called Takuwe, which means “why”, and it was all about the Wounded Knee massacre. He prepared all of this literature for us to read. He asked us, “What do you want to document?” He laid out a timeline for us. I specifically chose the aftermath [of the Wounded Knee massacre]. But I couldn’t really be just that one “vignette.” So I started speaking about the whole event in this painting and that led me into a lot of research.

It got pretty dark. I was actually at an artist residency when I was making that body of work. And I remember being alone in the studio, sitting there like, “Oh, man. I don’t think I can paint today after reading this heavy, heavy stuff.” But it’s very real. It can do a number on you. It did on me anyway.

It could get pretty dark sometimes.

I mean when I do those kinds of series, I’ll try to do these nonsensical paintings just for fun. Recently, I’ve been doing these small works that are just for exercise. But even then, with those little paintings I dabble in these ideas that might lead to something else. But I think that’s very common for a lot of artists to work that way.

I read the press version of who you are as a creative. How would you describe yourself as a creative individual? Is that part of your identity similar or different to how you would describe yourself in a different context?

Micheal: Yeah, I mean with the press release stuff, especially when you’re applying for grants and all that, there’s definitely a language that you have to put out there. But when I’m hanging out with other artists or with a young group of students, I’ll never lay those terminologies on them or try to scare them away. But when they’re ready to ask those things, they’re there.

“As far as my visual work, I want the audience to have a dialog with it and to interact with it. A lot of times the paintings are not very specific, they’re not telling the audience, ‘This is how you have to feel. This is how you have to think.’ It’s quite the opposite. I want the audience to engage it and ask questions like, ‘Why is this like this? Why is this happening? This is my interpretation of it.’ And for me, that is my ultimate goal—that dialog with the viewer or audience.” /Micheal

Why do you create? What is it that you’re creatively responding to or that compels you to create music or create art?

Micheal: That’s a tough one because you just do it, just like anyone else. But beyond that, most of the workshops that I give are to young, native students. And I love that—going into schools or other settings and teaching about art and our history, being that role of a teacher even though I’m not a professor or anything like that, and showing them, “Hey, if you’re interested there’s a rich history there that you can pull from visually or even sonically.”

When someone steps in front of your work, and maybe it’s different for different audiences, what do you want them to feel or experience? Whether that’s at a concert or in front of your visual work, do you have a sense of what your hopes are when someone interacts with all of those layers and complexities?

Micheal: As far as my visual work, I want the audience to have a dialog with it and to interact with it. A lot of times the paintings are not very specific, they’re not telling the audience, “This is how you have to feel. This is how you have to think.” It’s quite the opposite. I want the audience to engage it and ask questions like, “Why is this like this? Why is this happening? This is my interpretation of it.” And for me, that is my ultimate goal—that dialog with the viewer or audience.

Musically, it’s a little different because you’re already having this emotion, like we had this song called “Trick’s for Kids” and Reed’s voice is so powerful, it’s emotional. You can’t help but feel this emotion coming at you, so it’s a little different in that regard…

Do you feel any responsibilities as a creative to the people you’re collaborating with or the people that are observing or listening or viewing it?

Micheal: Now that I’m a little older, I think about those things. Will this next generation look at my work? What do I want to say to them—this younger generation like my nieces and nephews or even beyond that like the Lakota students? For me, that’s very important to have them look back at my work one day and say, “This is what was going on then.” Hopefully it’s not still going on. Maybe we fix things but I don’t know. But, again having a dialog with the younger generation is important.

It’s almost like the way Reed describes stepping into something that had been going on for a long time. It’s like this conversation that’s being handed off.

Micheal: Exactly. I like that.

I find it hard to imagine, given everything you’ve described, but Can you imagine a context where the act of creating isn’t part of who you are?

Micheal: Oh, geez. Like I said before, I don’t know how to do anything else [Laughing]. But in all seriousness, Doug and I actually had this conversation once. It was strange seeing other natives way back in elementary school as we were growing up because we were always pigeonholed as these “native people,” along with all the stereotypes that go with it. Like, “He’s either poor or he’s a criminal.” I think there are a lot of natives that don’t have art or music to fall back on emotionally. And when teachers are projecting that onto the native student body, they act out. Like, “Maybe I am this criminal they keep telling me about.” A lot of my peers from that time are either in jail or passed away. Not to say that our peers are going down that road, but if you look at it statistically in Rapid City, that’s what’s happening with a lot of the native student body. And you ask yourself, “Why is that happening?”

Douglas: We never finished school. I mean, we got our GEDs, but then we were like, “Enough of this.” I remember getting frisked and was like, “I’m out of here.” I didn’t do anything. At that time Columbine had just happened, and if you were a little weird, you were automatically considered dangerous. So I was like, “Oh, heck with this scene man, I’m getting out of here.” We had a great principal who cared, but whatever, we got out of there.

You used an interesting phrase and it just occurred to me. Do you see yourself as role models? Do you see a role that you’re playing in Rapid City or in a broader sense with the work you’re creating that does give an example of that creative life and being musicians and artists?

Micheal: You have to step into those shoes whether you want to or not. It’s the same thing with art and music. You’re thrown in those roles automatically. Sometimes you’re prepared for it, and other times you’re performing.

Reed: I think part of being a role model is also experiencing the fuckups, and having that be an example, “I did that. It didn’t go well for me, so you should definitely not do that too.” I look up to all my cousins in different ways because I’m the baby. But I’m almost 21, so I also have all my nieces and all my nephews that are really young. They do look up to me as well. It’s stressful and I’m definitely not to the point in my life where I would like to be, but I feel like I can be strong, and I am strong. I have to be strong for them, because being a native woman specifically, it’s hard.

There are not a lot of well-known strong, powerful native women. That’s part of my goal as a musician is to be that role model. Be somebody that these native youth can look up to, and can feel like they’re heard, that there’s somebody out there that actually is fighting for them. I think that that’s very important. I’ve fucked up a lot already in my short life, but I’ve also done some really cool things, things that I am proud of. So I think that that’s important to put out there…

There’s a lot of strong native women in my family that are doing better than a lot of the men, but we don’t get as much attention because that’s just the way that the world works. Because everybody focuses on something else, the white man, and then you go along the line and the natives are way at the bottom, but it’s native men, and then it’s native women. I’m overlooked a lot. People would rather start a conversation with my male cousins or any other male in my family, but I’ve got a lot to say. I’m a loud person. I can be loud, but I can take a step back. I can let other people talk, but I’ve definitely got a lot to say.

Micheal, you once said that there is life after death in art. When it’s all said and done, how would you like to be remembered as a creative?

Micheal: Oh man, I don’t know.

I guess I’ll leave that up to whoever wants to tackle it. I’m not going to say that my art’s going to live beyond myself or anything, but again, you put so much energy into something—you want it to exist for a while. I do have some pieces in museums, and they’re going to be there for a while. Maybe they’ll be pulled out once in a while. Who knows?

I once said there is life after death in art. But it’s funny. All the giants are dead. Again, they’re all white males, so what does that mean? I don’t have children or anything like that, so what is my legacy? You start thinking about that when you’re making art. I have a lot of pieces out there that I’ve sold. I don’t know where they’re at or who bought them. Maybe they’re on somebody’s wall. I think recently I’ve been trying to be more active in donating to museums that will preserve it, maybe have education around it. I think I would prefer that these days.

Douglas: There’s always the art critic that decides if you live or die, or how long you have a legacy. Isn’t there?

That might be the darkest thing you guys have said the whole time you’re here. You’re right, though.

Douglas: The art critic decides if you live or die. I’ve read some pretty weird stuff, even from just small critics in Santa Fe. I was like, “Wow. That’s mean.” They stopped serving wine at those things. It got meaner. That’s what I think. You’ve got to start serving wine at openings more often. You’ll get a nicer critic.

Micheal: But those kinds of questions that you’re asking are tough, because for an artist to be in that position, to think in those terms, is very privileged, because it’s like, “I’ve started this career. Now I can start selling this body of work for this price,” and it becomes economics, like everything else. Then you start asking, “Will it live beyond me?” and “Who am I” and that sort of thing. It immediately makes me want to reject that in a way. Maybe that’s why I’ve been focusing a lot more on community oriented things that are involving more people, rather than just the individual. Culturally speaking—Lakota culture—that’s what we’ve always done. So it’s nice being in collaborations, having collaborations with the community.

“I think part of being a native artist is living in and being in that discontent. Your whole life is seen as a joke by the American population, basically. People don’t think we exist anymore, or we are like a storybook. Our lives in general, let alone our art, has been brushed over. Living, existing isn’t comfortable—It’s made to be uncomfortable for us, the reservations and such.” /Reed

When you hear the phrase, “the great discontent,” what does it mean to you? How does it show itself in your work?

Reed: I think part of being a native artist is being discontent.

I think part of being a native artist is living in and being in that discontent. Your whole life is seen as a joke by the American population, basically. People don’t think we exist anymore, or we are like a storybook. Our lives in general, let alone our art, has been brushed over. Living, existing isn’t comfortable—It’s made to be uncomfortable for us, the reservations and such.

Micheal: I think a lot of Native Americans, if not every Native American, is that history, this romantic negative stereotype. Even when Reed was saying it about native women not being heard, that’s a direct result of negative stereotypes, where the male was always presented as this romantic warrior, when in fact that was not Lakota culture. The women were not below. Actually, it was quite the opposite. Even that’s skewed in Lakota culture, unfortunately, because of this discontent. That’s just touching on one little ounce of native America, one little pinch of that. But I wonder what that means to you [to Douglas]?

Douglas: Discontent?

Yeah. What does the great discontent mean to you in how you create?

Douglas: Oh, well, being told that you cannot amount to anything fuels this. You have something to prove when you’re younger. You are discontent. Then you get older and you just get wiser to it. You’re like, “Oh, well, it’s not about them anymore.” It’s about you. It’s about what you have to offer people—how you help your fellow human. It is a driving force, discontent.