- Interview by Tina Essmaker August 19, 2014

- Photo by Lou Noble

Molly Crabapple

- artist

- illustrator

- writer

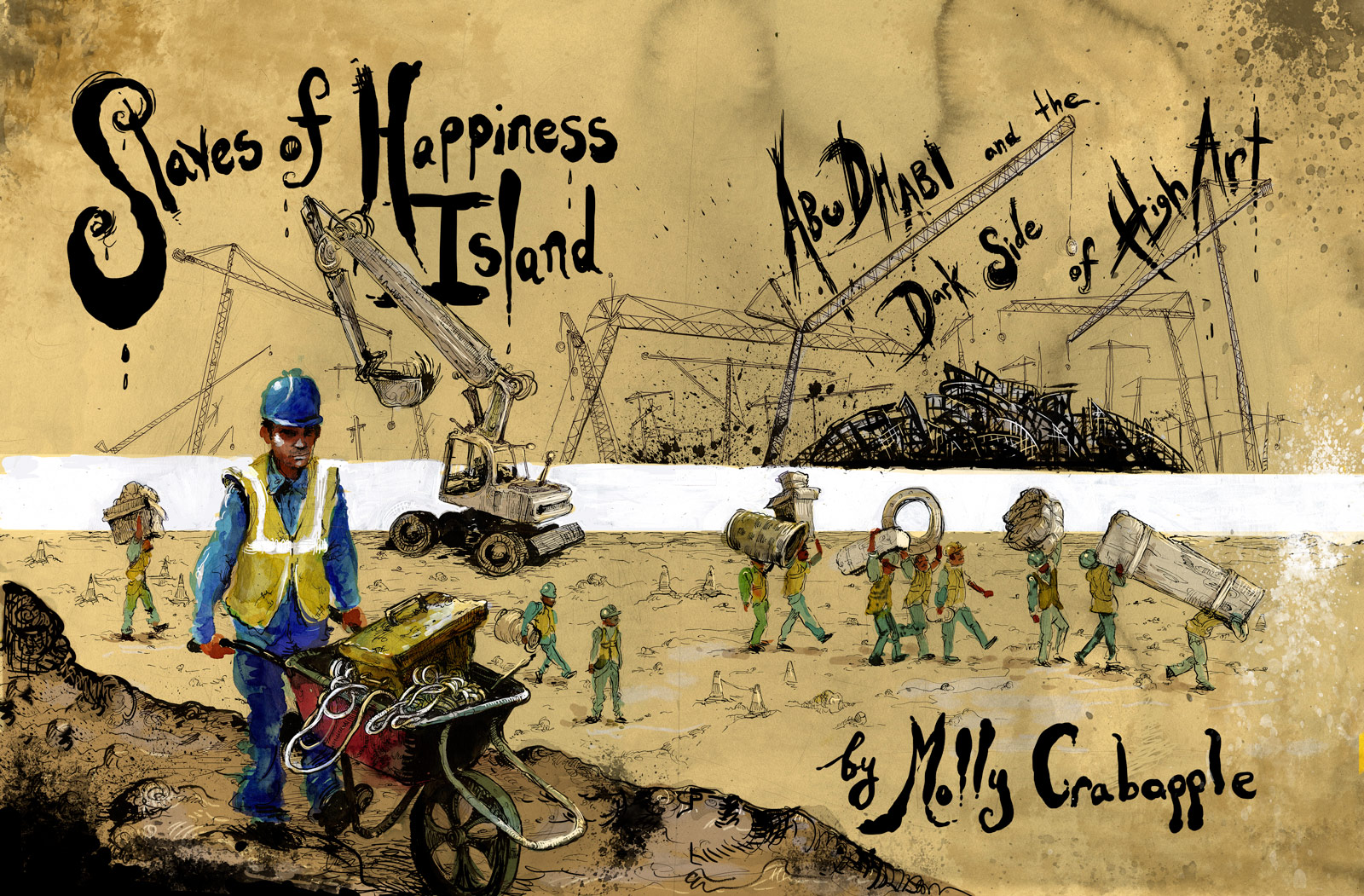

Molly Crabapple is an artist and writer in New York. Called “an emblem of the way art can break out of the gilded gallery” by the New Republic, she has drawn in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Dhabi’s migrant labor camps, and with rebels in Syria. Crabapple is a columnist for VICE, and has written for publications including the New York Times, Paris Review, and Vanity Fair. Her illustrated memoir, Drawing Blood, will be published by HarperCollins in 2015. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Two, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Two, available in our online shop.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I’m originally from Far Rockaway, New York. When I was eight, my parents split and my mom moved to Long Island. I was one of those bad punk kids who would sneak into New York City, drink in parking lots, and steal cigarette butts off of the floor and smoke them. I even tried to dye my hair with Manic Panic without bleaching it because I didn’t understand the mechanics of bleach. (laughing)

When I was 17, I went to Paris and worked at the Shakespeare and Company bookstore. It was amazing because I had a free bed in the heart of Paris for doing very little work, fairly incompetently. It was wonderful! That experience showed me a lot of possibilities for life, and I am grateful to George Whitman, the man who created and ran it. After that, I traveled around Europe for a bit before coming back to the United States to go to college.

I returned to New York to attend the Fashion Institute of Technology, which is a terrible art school—please, no one go there. I dropped out after a few years. When I was still in school, I started working as a model and burlesque dancer. I became a dancer because I was obsessed with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and I became a model because it was the only way I knew for a 19-year-old to make $100 an hour. I didn’t have the discipline or work ethic to be a stripper.

By the time I was 23, I had pretty much stopped modeling. I started Doctor Sketchy’s Anti-Art School, which was an alternative drawing program with burlesque dancers, drag queens, and underground performers who posed as models for people to sketch in bars. That exploded, and it’s now in over 140 cities around the world.

At 24, I was given the job of in-house artist for The Box, the most depraved nightclub in all of New York City. It was the most amazing opportunity. I was able to sit around and draw their customers as coke-addicted pigs and sketch their fantabulous performing models.

By the time I was 27, I was pretty successful, but I didn’t feel like I was doing work that was meaningful. I felt like I had eaten too many marshmallows: my artwork was all about beautiful girls, night life, the demimonde. I wasn’t doing work that I considered to be serious, and I was scared to do work that I considered to be serious because I was in the sex industry. That’s when I did a big project called Molly Crabapple’s Week in Hell, where I locked myself in a room in the Gramercy Park Hotel for a week and drew all over the walls. I figured I would know what I wanted to do after that.

After that, the Occupy Wall Street movement happened, which was right across the street from my apartment. I had always been political, but in a sort of silent way, where I would donate money or help in a more practical manner. I didn’t feel like I deserved to be vocal about politics because I was someone who drew girls with their tits out. But when Occupy happened, it felt like a moment where we all had to take sides. I tried to help however I could, so I ended up doing a lot of posters for the protests. It was a life-changing time: my apartment became a press room, many of my friends were arrested, I was arrested, and a lot of us forged friendships with people who were involved in other movements in their own countries, whether that was Spain, Greece, or Egypt. 2011 was a magical year—it felt like people around the world were sitting in the squares of their own cities saying, “Enough.” Even though these movements have been replaced by austerity or extreme repression in many countries, I still believe that year worked an alchemy on those people involved.

I was rather angry after my arrest. Not simply because I was arrested—I had a relatively easy experience—but because the NYPD does this to people all the time, for nothing but existing while brown or black. Being arrested is traumatic, but most people believe it’s trivial. If middle-class white people didn’t convince themselves that being arrested or incarcerated is something trivial, if they realized how bad it is, perhaps they wouldn’t be so goddamn trigger-happy about it. (laughing) I wrote about that experience for CNN, and I was offered my own column in VICE shortly after.

Since then, I’ve been combining art and journalism. I have traveled all over the world: Abu Dhabi, Syria, Greece, Spain, Lebanon, and Turkey. I’ve written for the New York Times and Vanity Fair. All the while, I’ve used my sketchbook kind of like a photojournalist uses a camera.

“…when Occupy happened, it felt like a moment where we all had to take sides…It was a life-changing time: my apartment became a press room, many of my friends were arrested, I was arrested, and a lot of us forged friendships with people who were involved in other movements in their own countries…”

Was creativity a part of your childhood?

My mom was an illustrator, but I’ve been drawing since I was four years old. In school, I was so non-functional as a student: I would draw during class and hand in test sheets unanswered, but covered in scribbles. Drawing is a sort of compulsion for me, like picking scabs. It’s how I interface with the world.

Was there a specific “Aha!” moment when you knew what you wanted to do?

Drawing is something I’ve always been into. I wanted to be a fiction writer when I was younger, but I wasn’t that talented. I wrote a terrible novel when I was in high school, which I luckily never put online, because it’s pretty grim.

When I was 17 and needed to hustle money, drawing was what I did. I would draw people’s pets, their kids, or even their Dungeons & Dragons characters. Because I knew how to draw realistically, it was a simple craft that I could immediately turn into cash.

Have you had any mentors or influential people in your life?

I’ve had quite a few, actually.

I met my best friend, John Leavitt, when I was 18. We were two rebellious, snotty, lazy kids, and we’ve been BFFs ever since. We pushed each other to be better and competed with one another. If his work was in the New Yorker, I’d say, “Aww, fuck you!” Then I’d try and do something to beat him. We’ve also collaborated on projects together: we ran a lot of Dr. Sketchy’s events together, and I did my first two books with John. We’ve been super tight for years and years.

The photographer Clayton Cubitt is someone else I admire. Are you familiar with his work?

No, I’m not.

He’s a photographer from New Orleans. He grew up in a poor family, but now does extremely high-end fashion photography. He has also done an album cover for Die Antwoord and a viral project called Hysterical Literature, which is about women having orgasms while they’re reading. That is probably his most famous project, because about 20 million people have viewed it. His work is so beautiful and his level of craft is so extreme, but he also engages with everything in the world. During Hurricane Katrina, he snuck past checkpoints to get back to New Orleans to find his mom and help his community. He also set up a makeshift photo studio and photographed the survivors from the communities he grew up in. The reason I love Clayton’s work, and one reason I think we’re such good friends, is because we see no boundaries between the types of work we do. A lot of people would say, “You do serious, gritty photojournalism,” or, “You do fluffy, beautiful fashion work,” or, “You did a video series about women having orgasms, and that’s sex, so that goes in its own box,” but he doesn’t see those projects as separate parts—he just sees life. He has a massive hunger and greed for life, as do I. I find that so inspiring. I hate the idea that artists should only do one subject or one style. I love the gluttonous, Pablo-Picasso-Diego-Rivera god-monster of modernism where you try to tackle the entire world with your art.

A person’s art is part of who they are, and someone can’t very well put himself or herself into different compartments. If you’re a photographer, then that’s what you do, regardless of what your subject matter is or where you’re taking photos.

Exactly.

“Ultimately, all we have is each other, and we have to take care of each other as communities, because I don’t feel like we live in societies that are going to do that for us.”

Do you feel a responsibility or a desire to contribute to something bigger than, or outside of, yourself?

I do, in a few ways. First of all, I’ve been so lucky to be a part of this community in New York and in the world, and to be a part of a community of people I love, whether they’re artists, writers, activists, or just fucking people. Ultimately, all we have is each other, and we have to take care of each other as communities, because I don’t feel like we live in societies that are going to do that for us. My primary responsibility is to my community, and whenever someone is in trouble, sick, arrested, or even just has to move and is too broke to afford it, we try to have each other’s backs, because who else is going to, right?

One of my primary drives is that I fucking hate hypocrisy. I hate it so much. I hate hypocritical, comfortable, self-congratulatory bastards who are complicit in terrible things. I like to eviscerate them with my art, and I believe that’s why I like journalism, too: I can speak to those people very honestly and demand that they tell everyone the truth. They may or may not, but at least I get to ask the questions.

Speaking of community, is being a part of a creative community important to you? Do you have a lot of community here in New York, or is it mostly online?

I have a huge amount of community online. I’m lucky to have a tight-knit group of mostly women here in New York who I’ve been friends with for a long time: we party together, we make art together, we get fucking shit-faced drunk together—which is why I feel like this right now. (laughing) One of my friends was hosting a reading last night and we stayed up very late.

But I do have a much larger community online. I have friends in Istanbul and London and Paris. The Internet enables this experience where you might speak to people very briefly in person, but you fucking love them based on a relationship you develop corresponding online. Even if you only see to them twice a year, it’s no less powerful because you’ve been pouring out your souls to each other online. Then, maybe twice a year, you’re fucking hugging each other so hard and passing out on the floor from drinking whiskey. (laughing)

Have you taken any big risks to move forward?

There have been instances where I’ve felt scared to do something, but those moments have been incredibly meaningful to me.

For instance, I wrote about my abortion for VICE when I hadn’t even told my mom about it yet. That was definitely something I felt a responsibility to do: I felt like one of the reasons abortion is so shitty for everyone is because women don’t talk about it, and the media pushes this narrative of, “Abortion is for teenagers who don’t know how babies are made!” Or, “It’s for women who are raped!” Or, “It’s for horrific medical conditions where the woman might die!” But if you don’t fit into those categories, then what the fuck are you, a monster?! A third of women have an abortion, and obviously the vast majority of them don’t fit into any of those categories. I wrote the article as a political message, but I was scared to do it. I was afraid of being stalked by crazy pro-lifers, honestly. (laughing) Yes, a bunch of people called me “baby killer” online, but that’s not too bad.

There are always people who will judge.

Yeah, but that article meant so much to a lot of women. Women from Northern Ireland who had illegal abortions wrote to me. One man showed my article to his mother who had an illegal abortion before Roe v. Wade was passed. Hundreds of women wrote to me about it. Out of any of the meaningful things I’ve done, writing that article was particularly important to me.

“I hate hypocritical, comfortable, self-congratulatory bastards who are complicit in terrible things. I like to eviscerate them with my art, and I believe that’s why I like journalism, too: I can speak to those people very honestly and demand that they tell everyone the truth. They may or may not, but at least I get to ask the questions.”

You talked earlier about traveling to do journalistic work. Is visiting conflicted areas a risk for you, and how often do you go?

I started doing it pretty intensely in the past two years. My first big journalistic story was when I wrote about going to Guantanamo Bay in 2012. I visited the island twice, and it’s a fucking horrific place. Recently, in the last four months, I went to Turkey—which is not a conflict area—to do a project on post-Gezi protest culture by going to demos and interviewing people.

I’m usually a bit nervous before I go to a place that might be a conflict zone. Places like Syria are obviously dangerous, but I feel privileged to see what geopolitics looks like up close, to see what other people aren’t able to see. I feel so lucky that people who live in areas of crisis take the time to speak to me, or show me around, because there’s no fucking reason why they should. I’m grateful for that.

One of the hardest pieces I’ve ever done was traveling to Abu Dhabi to write about migrant workers there. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) doesn’t have fixers the way other countries do. Insulting the government is illegal, and since most of the big construction firms have strong ties to the government, this censorship extends to them. Consequences for insulting the government can be dire—I interviewed a dissident, Ahmed Mansour, who spent eight months in jail for running a website that let people speak frankly. Emiratis are usually so well-supported by the government that there is no reason why they would take your money to do something that puts them at a very real risk. Everyone who isn’t an Emirati citizen, which is nearly 90% of the population, can be deported for virtually anything, even if they were born in the country. So they’re generally afraid to work with a journalist. I was nervous before I went to the UAE because I didn’t know how I would do it. I can’t drive, and I thought, “How am I going to get to these camps that are so far from the central city?” (laughing)

Do you normally travel alone?

Yes, I travel alone, but I often work with local fixers—who are often fantastic journalists in their own right–to do a story. In the UAE, I met an incredibly brave, knowledgeable local who uses the pseudonym Tom Blake. Between him and a translator, who I called Ibrahim in my VICE piece, I was able to get interviews with the Louvre. I ended up being able to get the information I needed, but I was fucking terrified that I wouldn’t because the UAE is so censored and surveilled.

A month after that, I went to Reyhanli in Southeastern Turkey to draw a mural in the Salam School for refugee kids—another project I feel privileged to have been able to do.

I saw pictures of that online! That’s so cool.

Thank you! I loved doing that. Those kids were so cool. I’m often skeptical of humanitarian aid initiatives where it’s a bunch of white people parachuting into a country in which they don’t know the language or the context, and they’re just doing unsustainable work. The teachers at the Salam School are also refugees, and they’re fucking brilliant. Many would be doing much more professionally prestigious things if life circumstances weren’t as harsh as they were. They give a stellar education to the kids.

The organization I worked with on that project, the Karam Foundation, was founded by two Syrian American friends, and almost everyone on the trip to Reyhanli was Syrian or of Syrian descent. They support the school year-round: they provided Internet and computers for the teachers, and installed a heating system for the winter. I was especially impressed by dentists from a group called the Syrian-American Medical Society. They fixed every one of the kids’ teeth.

That is wonderful.

It was amazing. There were kids who had been through terrible trauma and whose teeth were broken. The dentists not only fixed all the cavities, but they also did cosmetic work, so a girl whose front teeth had been broken off in the war could look like she used to before. And they were doing it all out of a makeshift clinic in a basement. They were such heroes.

I worked with some amazing people there. I met a children’s book illustrator from Damascus. My friend Lina Sergie Attar, who runs the foundation and is an architect, taught all the kids the basics of architecture. At one point, they brought in a Muslim boxer from Britain to do kickboxing workshops for the boys and girls. It was great.

Do you have any upcoming trips planned?

I’m giving an opening keynote at a media-tech-art event called The Conference in Sweden this month.

Do you finance your traveling through your personal artwork, speaking, or other work?

I get flown out for most of my trips, but sometimes I don’t. For example, the Karam Foundation project didn’t fly me out because they’re a charity, and spending all of your charity’s money to fly Americans out would be stupid. (laughing) When I went to Abu Dhabi, VICE paid for that—they generally cover expenses when I’m working for them. A lot of times, I’ll bundle projects: if someone wants to fly me out somewhere, I’ll look into other projects I can do in that same area so it’s cheaper.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

My family and friends are supportive, but my mother helped me become an artist because she is an artist herself. My mother influenced me with the idea that being an artist wasn’t just some airy-fairy-foo-foo career that you couldn’t make a living doing. She went into an office every day and drew pictures for packaging. Being an artist was a totally adult job that was a normal and rational path to earning a lower middle class income. (laughing) Because of that, I didn’t have to do what a lot of other people do: convince their parents or themselves that they can make a living as an artist. I said, “Mom, I’m going to school to become an illustrator,” and she replied, “Oh! That’s what I do!”

Are you creatively satisfied?

I don’t believe you can be satisfied and creative at once. Drawing art is hard, and frustrating, and you’re constantly trying to find your next project. If you were creatively satisfied, then you wouldn’t keep doing it.

That said, is there anything in the next 5 to 10 years that you’re interested in doing or exploring?

I want to do some big fucking murals. I’m also currently working on a memoir for HarperCollins, which will be coming out in the fall of 2015.

Wow! That’ll be here before you know it.

(laughing) Yeah!

Sorry, I don’t mean to stress you out. (laughing)

No, not at all! I just hate writing books so much. I’m sure I’ll be happy when it’s done, but it’s like fucking torture. I’d rather hit myself in the hand with a hammer.

It’s overwhelming to think about a memoir because it’s your whole life. Where do you even start?

Exactly. I’m on the second draft right now. I’ve forced myself to pick at the stupid thing for five hours a day. Last night I did a reading for some people about working at The Box and New York during the boom years, and they liked it. It’ll be done at some point. (laughing)

It’ll turn out fine. It’s just about putting your ass in the chair and saying, “Okay, I’m going to hammer away at this.”

Yeah. I’m almost done with the second draft, but each draft is a major progression from the first. The first draft is not even English—it’s a fucking pile of word swill that no other human can read. I took that, put it into English, and asked myself, “What do I still want to say with this?” I’m trying to make arcs, draw up characters, and put together scenes—I’ve never written dialogue before. With each step, I’m trying to chisel it out more and more from the pile of suck that it originally was.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out?

I have advice, but with this advice, I am making presuppositions. When you give advice to someone, you’re presupposing that this person has a fairly stable immigration status, that they don’t have a horrible, chronic illness that requires having health insurance, or that they don’t need to care for any sick parents or kids. Those are all circumstances I’ve never had to deal with, so I don’t feel qualified giving generalized advice for them.

The first piece of advice I have for people if they want to be a crazy artist like me is that companies are there to exploit you, and to extract as much labor out of you as possible while paying you as little money as possible. Always treat companies with intense cynicism and try to exploit them back as much as you can. The big mistake that will fuck you over in life is being a team player, because you’ll waste years and years of your life until you wake up one day having made some company a lot of money and having made yourself shit. That’s what happened to my mom. She never made much money because she was one of those people who said, “I’m going to work hard and be talented, and then people will recognize my value and reward me!” No, actually, they will just take your hard work and talent to make money for themselves and discard you when you’re no longer useful. So be very cynical.

That said, you have to work hard for yourself. I don’t mean the sort of bullshit notion of hard work where white-collar workers sit someplace staring at a wall for nine hours a day in a display of obedience. I mean that you should probably spend a lot of your twenties doing art from the time you wake up to the time you go to sleep, and turning down a lot of unnecessary commitments in service of that. First, because that’s what you need to do to be good enough so that when you have inspiration, your inspiration will lead to something; and second, because it’s almost fucking impossible to make a living drawing pictures, writing words, or playing music. Just the fact that we think we can do these things for a living is an intense act of hope and arrogance. If you want to be able to do that, if you decide to stake your claim on that path, then oh, my God you have to do such hard work! If you’re the sort of person who fucking whines about being motivated, like some of the art students I lecture, then just fucking stop. I’m not interested in speaking to anyone who wonders how to motivate themselves. If you need to talk about how to get motivated, then go get a normal job in the normal scheme of the world and just do art as a hobby so you still love it. Stop clogging up the field for the people who need this like a drug.

In summation: be cynical, work extremely hard, and hold your friends dear. Something else people won’t tell you is that the reason people go to Ivy League colleges isn’t usually to get an education, at least in the liberal fields. By going to an Ivy League college, you’re buying an entrée into the network of people who will one day rule the world.

That is so true.

It’s literally trying to buy your place in the upper class. But if you, like me, don’t come from a background where the people you were surrounded with as a kid were ever going to be influential and you don’t have either the academic or financial chops to go to an Ivy League school, you will have to build a network of influential people another way. If you’re ashamed of promoting yourself, the truth is that the people who don’t promote themselves usually have someone else promoting them. In Salvador Dali’s case, since he was a fucking twitchy weirdo, (laughing) his wife Gala promoted him because she was a well-connected and charismatic surrealist muse. Maybe you pay someone to promote you because your family is rich, or maybe it’s because someone is making enough money off of you that they can invest some of that money back into your career. However, very few people will ever promote you out of a pure belief in your talent, unless they’re sleeping with you, too, so there’s no more shame in promoting yourself than having someone else do it.

You’ll probably have to promote yourself in the beginning, because you won’t be that good at the start—and you won’t be good for years, so you’ll just have to keep working at it. Accept that you’ll probably do professional work that other people will see while you still suck. I have so much professional work from early in my career that is so fucking terrible that I don’t know why anybody ever gave me chances—I cringe when I look back on it.

We also live in an era where a lot of the old, supporting institutions are either opening up or crumbling, so I suggest that people don’t try to distort who they are to fit notions of what’s professionally viable, because that paradigm is over. I suggest you focus in on your weirdness, your passions, and your fucked-up damage, and be yourself as truly as you can. Express that with as much craft, discipline, and rigor as you can; work as hard as you can to build a career out of that, and then you’ll create a career that you love and that’s true to yourself, as opposed to doing what you think other people want and burning yourself out when you’re older.

Do you get a chance to speak to students often?

I do, but I’m skeptical of the idea of art school because I don’t believe what I do is scaleable. What art schools do in America is pretty cruel: they take a bunch of people and get them deeply into debt knowing that maybe two of them will ever actually be able to pay back that debt by succeeding in the field that they hope to work in. I do speak to art students, but I try to give them the caveat that I find the whole system morally reprehensible. I feel better when I speak to students in Europe, where their education is being funded by the state. That gives students more room to be experimental and use school to find themselves. It’s a lot harder to find yourself when you have to make payments on $50,000 worth of loans.

I went to school for social work and am still paying off a small student loan, even though I don’t work in that field anymore. I know people who owe much more than I do. In that scenario, you don’t have room to experiment or explore—you have to work a day job or take on whatever work comes your way. It puts you in a tough spot.

At least with social work, you need some sort of license or degree. There is no reason anyone needs to have a design or art degree. That is why I find the system to be even more cruel.

“You’ll probably have to promote yourself in the beginning, because you won’t be that good at the start—and you won’t be good for years, so you’ll just have to keep working at it.”

How does living in New York City influence your work?

New York City is a hard city to live in because it’s incredibly expensive, and it becomes more expensive every year.

Agreed.

Yeah, it’s fucking hard. The rent issue is so brutal. When I first moved here 13 years ago, it was much cheaper, but it was still expensive. My first place was called a junior one-bedroom, which was actually just a fucking studio. I paid $600 a month, but that was with two roommates. There was no light because all of the windows faced brick walls, and the shower was in the kitchen. The three of us hated each other by the end of living together. If we had stayed one more day, it would have been Lord of the Flies. In my next apartment, my room was the size of a large throw rug, but it felt luxurious because I had a door. (laughing)

I tend to joke that the ultimate attainment of New York—the fucking golden, glittering ring you reach for—is when you have a washing machine in your apartment. (laughing)

Or even in your building!

Yeah!

If you have a washer, dryer, and a dishwasher, you’re golden.

Exactly! In the suburbs, that’s not an attainment. My mom didn’t make more than $40,000 a year in her entire life, and living outside of the city, we always had a washing machine. Here in New York City, that $40,000 a year might not even get you within blocks of a laundromat.

Because of that aspect of living in New York, you become jagged, ready to hustle, and desperate. I often compare it to being a deep sea fish that explodes if it goes into lower-pressure atmospheres. Sometimes when I visit my boyfriend’s family in Western Pennsylvania, I think, “God, there’s so much space and room, and everything is so slow.” The crushing speed of New York definitely influences my work, but conversely, I am able to find so many more opportunities because everything is here.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I wake up around 10am, have a lot of coffee, and make a to-do list. I usually try to do my drawings early because they’re pretty easy for me. Then I talk on the phone with my mom. Then I go to a restaurant to type for about four hours and leave a large tip to make up for my obnoxiousness in doing so. (laughing) A lot of times, I’ll have a friend or a party over for whiskey at night and then stay up until 4am.

Speaking of, I should probably get on with what I have to do for the day.

Of course! I just have one last question for you: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I want to show artists that they can do everything in the whole fucking world.

“…focus in on your weirdness, your passions, and your fucked-up damage, and be yourself as truly as you can. Express that with as much craft, discipline, and rigor as you can; work as hard as you can to build a career out of that, and then you’ll create a career that you love and that’s true to yourself…”