- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker February 12, 2013

- Photo by Anthony Batista

Scott & Vik Harrison

- designer

- entrepreneur

- nonprofit

In 2004, Scott served as a photojournalist for Mercy Ships in Liberia, West Africa, where he learned the life-threatening effects of contaminated water. Upon moving back to his home in New York City in 2006, he founded charity\: water, a nonprofit bringing clean and safe drinking water to people in developing nations. Vik attended the School of Visual Arts and began her career at Süperfad, an NYC design house. She left the for-profit world in 2007 to come on full-time as charity\: water’s designer and creative director.

Interview

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue One, available in our online shop.

Scott, we know some of your story because it’s on the charity: water site, but Vik, we don’t know much about you. Would you both describe your paths leading up to charity: water?

Vik: I was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1983 during communism, and the country was basically shut off to all foreign influences. My parents were both artists: my mom was an enamel painter and my dad made jewelry and was a musician. My first exposure to anything creative was through my dad, who smuggled Beatles albums into Russia and made copies for all his friends. You couldn’t get them in Russia at that time because the government was opposed to all foreign media, but he thought the music was important enough to risk being arrested. He was a rebel who hated living in communism; he always wanted to leave Russia.

The Iron Curtain fell in 1991 and the minute it did, my dad got a plane ticket out, went to New York City with $2,000 in his pocket, which he borrowed from his brother, and started preparing a life for my mom and me. We joined my dad a year later. We were poor immigrants and my family always wanted me to have a job that would make money, but I came from a family of artists and that was all I knew. At first, I thought I would be a fine artist, perhaps a painter, but my parents were against that. They had sacrificed their entire lives and left their home country to bring me to America so I could have a job that would earn money. Because of that, I tried to consider jobs that would combine art and the ability to make money.

From there, I decided to learn how to make art on the computer and after high school, I went to School of Visual Arts here in the city; I studied digital design, motion graphics, and 3-D animation. I thought that working at an ad agency and coming up with creative campaigns for big brands would be my dream job. I came out of my junior year with an internship, which turned into a full-time job after my boss convinced me that I’d learn a lot more working than I ever could in school. I will always be thankful to him for that, because in my case, he was right. I had so many student loans; I was just happy to have a job and start paying them off.

The full-time job I took was at a little production company in Midtown. We worked with big agencies to craft advertising campaigns and our clients were the usual suspects—Coke, Pepsi, American Express, and makeup clients. For a few years, I loved it. I got to see what the inside of an ad agency was really like behind the scenes of all the commercials I had watched on TV. About two years into it, the allure wore off. I started to see how much thought actually went into manipulating people to buy products they didn’t really need, which probably put them in debt and didn’t make them happy anyway.

I started wanting something more. I still believed that design was inherently good. There is so much power in good design, but it seemed underutilized in the ad community and I wanted to apply it to help solve big problems. Long story short, I tried to volunteer for a few humanitarian organizations in New York City. I really just wanted to volunteer one day a week to feel better about myself.

One day, I was outside of my East Village apartment, talking to a neighbor about my desire to volunteer and he said, “I have this friend, Scott, who just came back to America after living in the poorest country in the world for two years and traveling on a hospital ship. He wants to start a water charity.” I truly didn’t know that there were people in the world who didn’t have clean water, but anything sounded great to me. I asked my neighbor how to get involved and he told me that Scott was kicking off charity: water the following week by doing an outdoor exhibition in NYC’s parks. My neighbor invited me to come and volunteer.

By the way, my parents from communist Russia had no concept of charity and didn’t understand why I would do anything for anyone for free.

The day of the charity: water event, I showed up at Union Square to volunteer and I met Scott. I shook his hand, he gave me a shirt and said hello, and then didn’t say anything to me for the next eight hours. I passed out fliers to people on the street and was completely naive. I didn’t know anything about charity: water because I hadn’t read the 20-page Word document of water facts that Scott emailed me the night before. (laughing) But I had the best day; for the first time, I felt like I had served and it was small enough that I felt like I really made a difference.

During the event, most of the volunteers came and left throughout the day, but I stuck around the whole time. I think Scott figured he should come over and find out a little more about me. He asked what I did and I told him I was a designer. I also told him to let me know if he ever needed any design help. He said, “Okay, I’ll call you,” but I figured he’d never call. I got a call from him the next day and he said, “Why don’t you come over and we can talk about it?” I thought that his organization was a little bit bigger than it was. I didn’t know that he was working from the couch in his living room—

Scott: It wasn’t even my living room—it was a friend’s living room.

(all laughing)

Vik: So I arrived at 109 Spring Street at 8 o’clock at night and here I am at this guy’s apartment. I thought, “Oh my gosh! This is going to be weird,” but it wasn’t. We had an amazing conversation and then I showed him some of my work. I was still such a junior designer at the time, but he asked me if I could work for free and I said, “Yes!” I started working nights and weekends on top of my day job in order to develop the look and feel for charity: water. Six months later, Scott finally had the money to hire me and I came on full-time.

“I decided to give it a go to see if I could be part of ending the water crisis before I died. I also wanted to reinvent giving and the way people think about charities.” / Scott

Did you come on as the creative director?

Vik: I actually just came on as a designer at first. At the time, we weren’t even thinking about titles. We were just thinking about what needed to be done and if someone could do it, we let them. Then, as the team started to grow around me, I became the creative director.

What do you do as creative director?

Vik: I make sure our brand is consistent and represented well through copy, design, video, photography, and the storytelling we do for campaigns.

Well, you do a great job. It’s very compelling. So, Scott, what’s your story?

Scott: I have a little bit of a prodigal son story. I was born in Philadelphia and grew up in a conservative Christian family. My mom got really sick when I was four years old and became an invalid for the years I was growing up. My parents wanted to have a bigger family, but didn’t, so I grew up as an only child. I was a good kid—I was active in the church, played by the rules, took care of mom. Then I turned 18 and like so many bad clichés, I rebelled, grew my hair down to my shoulders, joined a band, and fell in love with New York City and its possibilities. I slipped into the decadent lifestyle the city had to offer and one by one, found myself doing all the things I said I would never do.

My band broke up almost immediately because we didn’t really like each other, but the guy who was booking my band in the clubs was making a lot of money and seemed to have the life. He worked a few nights a week, drank for free, his friends drank for free, and he got paid for it all. I stumbled into the role of a nightclub promoter and over the next ten years, I climbed the ranks of New York nightlife. I started out promoting R&B parties at Nell’s, a legendary club on 14th Street. We’d have people like Prince, Chaka Khan, Stevie Wonder, and Bobby Brown come and sing open-mic for a few hundred people. Then I moved on to the trendy fashion scene clubs where people would pay $400 for a bottle of vodka that we bought for $25. At 28, about a decade in, my life looked pretty nice on the outside—I had a nice watch, a grand piano in my apartment, a great dog, and I was flying around to all the right places for Fashion Week.

Then, on a trip to Punta Del Esta, Uruguay, with beautiful people, the music kind of stopped. I realized how deeply unhappy I was and how far I’d come from morality, spirituality, and all the things I believed so intensely as a kid. I was a jerk; I had turned into a horrible person who only cared about himself. On this trip, far removed from New York, but not the scene, I was getting wasted every night and reading theology while hungover each morning. That’s when I rediscovered a lost Christian faith in a more meaningful way, on my own, as an adult rather than having it force-fed to me. I decided to go back to NY and try to live it out with integrity. It took me six months of floundering before I finally found an opportunity to get completely out of nightlife.

To me, the opposite of my selfish life was serving the poor for no money, so I started applying to a bunch of humanitarian organizations and, to my surprise, nobody wanted me; I was rejected by every organization I applied to. They probably thought, “Nightclub promoter? We’re not letting him anywhere near the good work we’re doing.”

One of the organizations I applied to volunteer with is called Mercy Ships. They were leading a group of doctors and surgeons to Liberia on a hospital ship. I applied to be their volunteer photojournalist because, in the midst of all the nightclub stuff, I had actually gone to NYU and earned a communications degree. I told the organization that I knew a lot of people who I could share the photos with because I had 15,000 people on my nightlife list, plus I was a pretty good photographer and writer. They initially rejected me and then, for the first time in the organization’s 25-year history, they were preparing to go on the trip and didn’t have anyone to fill the coveted photojournalist role. They went back through their rejected applicants and called me. They said, “We haven’t agreed to take you on, but we’ve agreed to meet you.” I went to Germany to convince them that I would not throw wild parties on the ship or corrupt the other volunteers. What was cool was that it was very opposite of my life in that I had to pay them $500 to cover room and board each month—all for the pleasure of volunteering.

When I moved into the ship, I felt sorry for myself. I had a couple hundred square feet that I shared with two strange roommates, the ship was 50 years old, and there were cockroaches. However, once I got to Liberia and started understanding how the people were living, I didn’t feel sorry for myself anymore. The country had just come out of 14 years of civil war and had no public electricity, no running water, no sewage, and no mail—it was completely decimated.

I spent the year photographing the work of the volunteers and then I signed up for a second year and went back. During the second year, I started understanding that dirty water was making so many people sick. Part of my job was to photograph a small water team, led by one man; they went into the villages to help the locals dig a few wells a year. I saw people drinking from nasty, green, slimy swamps and when I went back a couple months later, everybody was drinking clean water that came from 40 feet under the ground for a few thousand dollars. While I was certainly struck by the surgeries and medical work that I saw on the ship, the guy who seemed to be having the biggest impact was this volunteer working on water.

After my second year of volunteering, I came back to New York. I was 30, had no money, and crashed on the couch of an old nightlife friend. I decided to give it a go to see if I could be part of ending the water crisis before I died. I also wanted to reinvent giving and the way people think about charities.

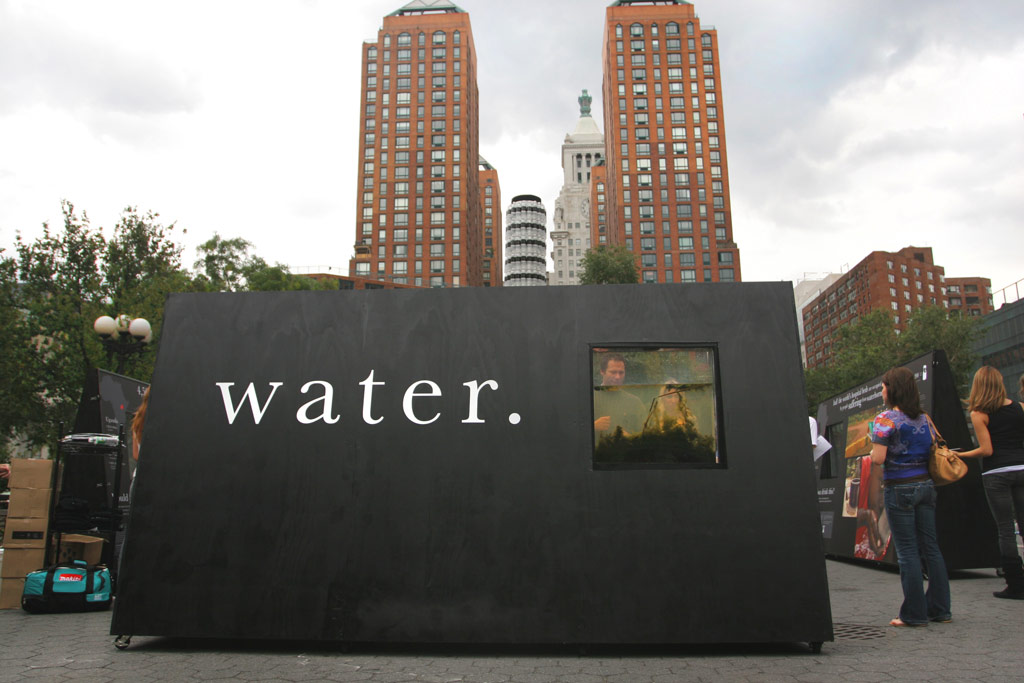

Charity: water started with a birthday party on September 7th, which was my 31st birthday. A month later, I got this crazy idea to take dirty water from NYC ponds and rivers and put it in tanks to show people in the streets of New York what it would look like if they had to drink from a nasty pond. We juxtaposed that with photos of people around the world actually drinking dirty water. Then we asked people to buy a $20 bottle of water, which could help one person get clean water.

Vik: That was when bottled water wasn’t awful.

Scott: Yeah, we went green a year or so after that, but it was an interesting, shocking gimmick. We all know that bottled water feels a little gratuitous, so asking people to pay $20 for one bottle and using 100% of that to bring people clean water worked; people thought it was a great idea. I met Vik while she was helping staff that crazy exhibition in the second month of charity: water.

Ryan: Did you know anything about nonprofits when you started?

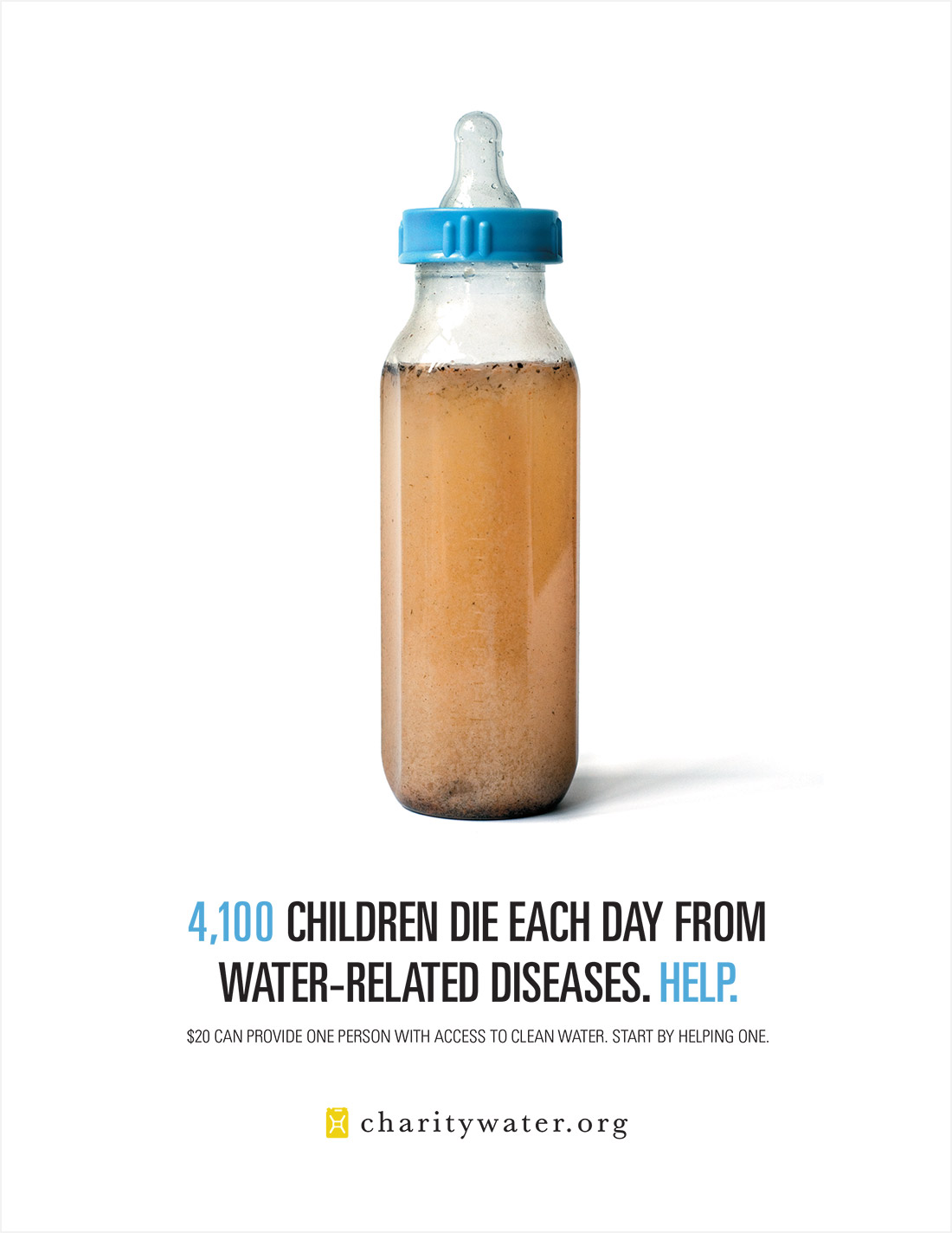

Scott: I think I knew what I didn’t want to do. I didn’t want to direct mail people. I also didn’t want an ugly website. I thought that nonprofits at the time had some of the worst websites out of all the sectors. They were bad at using visuals, bad at telling stories, and at the time, I wasn’t sure if that was because of bad taste by leadership or a poverty mentality of “our stuff can’t look too nice.” I think that sometimes it’s both.

From day one, I wanted to build a brand and that was key. There wasn’t a single charity brand that I looked up to; there are big charity brands, but they’re not really awesome, cool, or aspirational. I was inspired by Apple’s marketing and simplicity and I wanted to build the Apple of charity. Although I could check the “good taste” box, I didn’t know how to design anything. I needed to find someone who could and I was fortunate enough to find Vik, who was the second hire in the organization. Our first hire was the person who would go work on the water projects we would fund around the world; the second hire was to help build the brand, which shows how much that was valued from the start.

Ryan: I like how quickly your paths crossed.

Vik: Yeah, and neither of us knew how to run a charity at all.

“From day one, I wanted to build a brand and that was key…Although I could check the ‘good taste’ box, I didn’t know how to design anything. I needed to find someone who could and I was fortunate enough to find Vik…” / Scott

Tina: I think there’s a benefit to not knowing because then you approach it differently.

Scott: Yeah, we’ve heard that. We have some of the most amazing people who have come out of nonprofits and now work in our finance department, so there are certain departments that you want to have a high pedigree of stewardship and financial management. But sometimes what you don’t know is your greatest advantage. A nightclub promoter starting an organization to raise a hundred million dollars sounds stupid, but in some ways, I was uniquely qualified after ten years of getting people really excited about getting wasted, right? It was, “Get past my velvet rope to spend all your money and get nothing except a hangover and maybe some shame the next morning,” to, “Let’s help get one billion people clean water. We’ll create a way where 100% of your money helps; we’ll show you where your money goes. We can do this.” It was about inviting people to a different kind of party.

Scott, you already shared about this, but Vik, did you have a specific “aha” moment when you knew what you wanted to do?

Vik: I always knew I wanted to focus on art and design, but the big “aha” moment came for me when I realized I could use it for good. David Berman says, “The same design that fuels mass overconsumption has the power to repair the world.” I didn’t know you could fix the world with design until I met Scott, who taught me that charity doesn’t have to be boring and, in fact, it would greatly benefit and distinguish us if we weren’t boring.

Did either of you have any mentors along the way?

Vik: There’s a friend who I worked with back when I was really junior. Her name is Erin Sarofsky and she’s incredibly talented; she now has her own agency in Chicago. We worked together at Süperfad and became really good friends. She didn’t necessarily mentor me, but I learned a lot from her. When I first started designing, everything in me wanted to immediately knock down my work when I showed it to others so that no one else would. Erin, on the other hand, walked into meetings with confidence and would say, “This is what I made. Here’s how I think it can work. This is why it’s awesome. Here’s why you should believe in it.” The way she talked about and pitched her work as a designer was so incredibly inspiring to me. I learned so much from her about how to be confident when putting something together and presenting it to the world.

Scott: I had a mentor on the ship. His name is Gary Parker and he was the chief medical officer. He had volunteered to do a couple month stint and that was 25 years ago; he just never left. He gave up his plastic surgery career to serve the people of West Africa.

Over the last few years, I’ve also had an amazing tech entrepreneur, Ross Garber, as a mentor. In 1996, he built a company called Vignette, which he took from zero to something like 2,000 employees in three years. He’s been instrumental in helping me build and grow charity: water. His feedback is very candid and honest and it’s been transformational in my growth and the growth of the organization.

“I truly believe that people are looking for stories that really mean something—stories that are redemptive, inspiring, and bigger than an individual.” / Scott

Has there been a point in either of your lives when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward?

Vik: I quit my job and went to work on Scott’s couch.

Scott: I wanna add some color.

Tina: Let’s make this interesting.

(all laughing)

Scott: She quit her job, took a pay cut, gave up her—

Vik to Scott: Wait, are you talking about Liberia?

Scott to Vik: Oh, yeah!

Vik: Hold on. First, I have to tell you what I did to get myself over there. I took this shady job to animate a commercial for a 1–800 number you call if you want to find out who your true love is—you know, like the ones you see on MTV at 4am? I was so embarrassed about it, but I don’t care now because it gave me $5,000 to buy a plane ticket to Africa so I could see the work charity: water was doing.

Scott: We couldn’t afford to send her.

Vik: Prior to the trip, I had quit my job with all its health benefits and started working at charity: water with zero anything. So, I went to Africa, had an amazing trip, got back, and found out that I had malaria. I went to the hospital, stayed there for three days, got treated, and was sent home with a bill for $40,000. Scott was in debt and I owed two months on rent—we were just freaking out.

The amazing story that happened was I called my old job’s HR department, which was in Seattle, and spoke with a woman about my situation. I told her I quit work last month and now have a giant hospital bill. I asked about COBRA and she put me on hold to look at my file. She came back and told me, “I don’t know how this happened, but someone here forgot to cancel your health insurance, so you’re completely covered. I’m just going to pay this all off for you and then cancel your insurance.” Scott and I were in tears.

Scott: I think one of the big things for charity: water was this 100% model. It’s very, very rare and unique. There are some organizations that have done it with huge endowments or 100 million dollars in the bank, but we started on a couch with no capital. We said we were going to build two businesses from the start and then build them in correlation with each other—everyone said it was stupid. I remember opening up both accounts: the one we would someday pay our staff with and the other where public donations would go and never be touched, except to be sent to the field. It worked so well that we raised millions of dollars for clean water, but always struggled to have enough in the account to pay our staff.

People loved the idea of all their money going to a water project, but we hadn’t figured out how to tell the story yet. I was really discouraged and knew that the 100% model was bringing a new group of people back to giving; they were getting excited and trusting again. I hadn’t yet solved the business problem, but the risk paid off. An entrepreneur, who was a complete stranger, had just sold his company to AOL and he spent two hours with me and wired 1 million into our bank account a few days later. That gave us 13 months of runway to build the business. During that time, we figured out how to tell the story and get people really excited about funding staff salaries.

“I didn’t know you could fix the world with design until I met Scott, who taught me that charity doesn’t have to be boring and, in fact, it would greatly benefit and distinguish us if we weren’t boring.” / Vik

Are your families and friends supportive of what you do?

Vik: Actually, my family was completely pissed off at first. They didn’t bring me to America to be poor, work in Africa, and fly on dodgy airplanes to strange countries. They were mad at me for a while, but now they get it and love coming to our events.

Scott: As I said, I was a bit of a prodigal son, so the moment I got on that ship, my parents ended ten years of prayers with a sigh of relief. Mom and Dad have licked their fair share of envelopes around here over the past few years—we put them to work.

Ryan: I think we can skip the “do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself” question.

(all laughing)

Are you guys satisfied creatively?

Scott: I’ll speak for both of us and then see if Vik agrees. I don’t think we’re ever satisfied; it’s in our nature that nothing is ever good enough and that’s actually been a problem at times. If the leaders of an organization don’t ever think anything is executed to the standard of excellence that they hold themselves to, it can create some problems. We’ve been trying to celebrate wins around here. For example, we have an amazing year, grow 90%, crush all of our goals, and we’re asking, “Why couldn’t we have grown 100%?” Creatively and with respect to everything we do, we have such high standards.

Vik: I absolutely agree with Scott, but so many times I feel like I am faking it. I feel like someone is going to find me out and say, “You don’t know what you’re doing.” It’s been six years with charity: water and when people say good things about what I’ve done with the brand, I think, “I don’t even know what I’m doing.” It’s great and scary at the same time. I always feel like I need to be reading more books and learning.

Is there anything you’d like to do in 5 to 10 years?

Vik: I would say that right now, we are still trying to achieve real growth as an organization. We’ve proven the concept and we’ve gotten the early adopter market to be really excited about charity: water, but we haven’t made it in the big leagues yet—we’re not a household name. Once we’re able to make that happen, I’d love to do some interesting things around brand and community building that are not tied to raising money or revenue goals, but are just for the sake of doing amazing, fun stuff. I’d love to do community events with awesome designers or graffiti artists and do it for the sake of having a good time and inviting others into it. Right now, we’re pressured to grow financially, so we’re not at leisure to do other stuff, but I’m excited for when we can.

If you could give advice to a young person starting out, what would you say?

Scott: All this stuff comes out sounding like clichés. There were two things that were key in getting charity: water off the ground. First, tenacity like a bulldog. People told me no, but I just kept going.

The second thing is storytelling. I truly believe that people are looking for stories that really mean something—stories that are redemptive, inspiring, and bigger than an individual. Our work lends itself so easily to those stories, plus I’m a visual thinker. I love telling stories and telling them visually, which is a really effective way to communicate to people.

Vik: Something that Scott taught me was to be blissfully unaware of the fact that you might fail. In the beginning, he didn’t even think failure was a possibility. Actually, we just had a conversation about a guy we want to hire and I said I wanted to bring him into our office and convince him to work with us. Scott said, “What do you mean ‘convince’ him? Everybody in the world wants to work at charity: water.” I replied, “How do you know?”

Scott: In the humblest way, who wouldn’t want to give clean drinking water to a billion people and do it in a fun and creative way?

Vik to Scott: Most people don’t have that extravagant belief that what they are doing is important to everyone. That’s why you’re able to walk into anyone’s office and have the confidence to talk about what you do.

The last piece of advice I would give is really practical. When I first started creating, nothing that I created looked how I wanted it to look. I’d start with a vision and come up short of my goal; I failed over and over, but every time I tried, I got closer to my goal. I think that doing a lot of work and taking on every project you can when you’re young is important. Now, I’m finally to the place where most of my work comes out how I had envisioned it, but it took ten years of work to get there. Just keep designing and doing lots of work and it will slowly get better until one day, you will make something that looks how you wanted it to look, which is really rewarding.

How does living in New York City impact your creativity?

Vik: We live in TriBeCa and there are always new, little places popping up—like All Good Things on Franklin Street or Best Made Company on White Street. These places are so simply and well-designed and because I go to them every day, it starts bleeding into my work.

Scott: Well, we live in a 72-step walk-up, so that keeps us fit. (laughing) It’s funny because one of the criteria for me when looking for an apartment was being able to walk to work. We can do that because it’s only about 20 minutes to the office, but I might have walked three times last year; I just got so busy and it takes five minutes to take the subway there. I wish I could say I was walking to work. That’s something I want to do more this year.

Is it important to you to be part of a creative community of people?

Vik: Definitely. We have so many creatives who do campaigns for charity: water and the staff we have are also creative and incredibly talented. Staying in that world is sometimes hard, though. We have to be intentional about it because it’s really easy to get sucked into the world of organization and management and staff meetings. We try to meet with people and I’ve been a lot more intentional about meeting with people who inspire me and who are thought leaders.

Do you guys have a typical day?

Vik: We wake up, get coffee at Blue Bottle on Franklin, and take the A train two stops to work.

Scott: Work for us starts at 9:30am.

Vik: I’m a total night owl and Scott kind of is, but—

Scott: I’m trying to be a morning person.

Vik: I’ll come into the office around 9:30–10am and most of my day is filled with meeting with my team, reviewing their work, and making sure they’re not stopped from working for any reason. My day is full of that along with emails, meetings, and answering questions. After work, I’ll come home, open a bottle of red wine, and actually work on creative things on my couch from 6pm to midnight.

Scott: I don’t have a typical day. I did 90 flights last year, so there’s tons of travel. There are no themes to the days. When I’m in the office, sometimes it’s all internal, sometimes it’s all external, and sometimes I’m running around in Midtown asking people to write big checks. It’s super varied, which I like.

Vik: The thing to note is that we don’t have a work and life separation and we don’t crave that. The more integrated our work and personal lives are, the less stressful it is. We love working on our laptops with a glass of wine while watching TV. Work and life are really fluid for us; we’ll work on the weekends, but sometimes take half a day off during the week.

Scott: We talk about work while on vacation. It’s still cool because we’re by the pool, talking about work.

“…we don’t have a work and life separation and we don’t crave that. The more integrated our work and personal lives are, the less stressful it is.” / Vik

Water Changes Everything.

Animation by Jonathan Jarvis. Narrated by Kristen Bell. Score and sound effects by Doug Kaufman.

Tina: We do the same thing. When you enjoy what you do, it doesn’t feel like work.

Alright, just a few more questions. Favorite music?

Scott: The Lone Bellow; they’re friends of ours and they’re killing it. I’ve also been listening to a lot of Oscar Peterson these days; I’m rediscovering jazz.

Vik: You are?

Scott: Not with you, cause you don’t like it.

(all laughing)

Vik: Maybe one day.

What’s your favorite TV show?

Scott: Downton Abbey! I’m totally hooked.

Vik: I like Homeland.

Any favorite movies?

Vik: The movie that I saw that made me want to work in charity is The Constant Gardener. I watched it on my mom’s couch when I was 22 and had no idea that the world lived the way it lived—until I saw that movie.

Scott: I’m going to go with Tree of Life. I loved every minute of it.

Your favorite book?

Vik: I love The Method Method, which I just read. It’s the story of the two guys who started the Method brand and it’s really good. Also, Wabi-Sabi:for Artists, Designers, Poets, & Philosophers by Leonard Koren. Jack Dorsey told Scott about it and it’s one of the books they give you if you visit Twitter’s headquarters. It’s all about simplifying your life, your design, and your world. It’s also about seeing beauty in ordinary things based on an ancient Japanese philosophy—I want to learn to live like that.

Scott: I love The Message, which is a very modern day translation of the Bible, put into what’s almost slang, which has a very different feel.

Favorite food?

Scott: The Master Cleanse, which I just started today. It’s going to be my favorite food for the next 14 days.

Vik: The truffle crab pizza at Mehtaphor in TriBeCa.

Scott: I will not disagree with that—best thing in the world!

What kind of legacy do you two hope to leave?

Scott: I hope to have inspired hundreds of millions of people towards generosity and helped hundreds of millions of people get clean water.

Vik: I would love to reinvent giving for our generation and future generations in order to make giving and helping others cool again.

Join us in changing lives with water!

You didn’t think we’d do an interview with Scott and Vik and NOT do a charity: water campaign, did you? Giving back is important to us and we know it’s important to you, too. That’s why we want to take this opportunity to ask you to join us for a cause that truly is greater than us—bringing clean, safe drinking water to people who need it.

We’re raising $5,000 for clean water, 100% of which will go straight to funding water projects. Let’s do the math: If 500 people give at least $10, we’ll reach our goal. What do you say? Let’s make a difference—because water truly does change everything.