- Interview by Brandi Katherine Herrera December 5, 2017

- Photography by Lyndon French

Laura Letinsky

- artist

Laura Letinsky grew up in Winnipeg, where she had the freedom to experiment artistically without any concern over who was watching or judging her. Having since made her life in the US, she continues to push societal norms and expectations though the artwork she makes. From her studio in Chicago, she spoke to us about the roles that tenuousness and imperfection play in her process, why it’s important for her to provoke and unsettle by way of the photographic still life, and how there’s really no such thing as ‘balance’ in her life as an artist, professor, and parent.

What it was like to grow up in Canada, and in what ways did your upbringing influence your ideas about art and creativity? Canada is different in so many ways—some more obvious than others. Winnipeg, Manitoba, which is where I grew up, was so far from New York City. It was isolated, and things were quieter, and slower; especially back then before cell phones or the Internet. On any given night, I could attend all of the things that were happening, whereas in a bigger city there’s no possible way to keep up with everything.

Things felt manageable there, outside of the mainstream. This was a kind of liberation—it didn’t matter what you were doing, because you weren’t being observed. There wasn’t that sense of Oh my god, this has to be great! It felt more like, Well, no one’s ever going to see this anyway, so what does it matter? I think that provided me with a lot of freedom.

Winnipeg has generated a lot of idiosyncratic art, including the work of artists like Marcel Dzama and Jon Pylypchuk, who came out of the Royal Art Lodge, as well as musicians like Neil Young and Joni Mitchell who grew up close by. But the Canadian art scene is different, because it doesn’t have the same market or educational system, and I became aware of that as soon as I went to graduate school. In the US, education is a corporation. There’s vying amongst institutions to attract students, and students feel pressured to attend the best possible school. Where I grew up, we simply went to our local college, took our courses, and often moved out on our own and worked part time.

I was shocked when I went to grad school at Yale, and everyone’s teeth were straight and students drove nice cars. (laughing) There were Saabs and Volvos on the street! I’m acclimatized to it now, but it was a real surprise to me then.

Did you have the feeling that no one was really watching what you were making from a very early age, or was that something that you recognized in hindsight as a grad student in the US? It was more of a realization at Yale, when I was in the fray of it all. I’d been accepted to a Canadian graduate program, and I remember thinking, You know, I can always come back to Canada, but if I don’t go to the US now, I may never get the opportunity to enter into this system again. I decided to go, and I’m really happy that I did. It was an amazing experience, and I learned so much. It really opened my eyes.

“The sudden nature of my father’s death made me aware that there’s just one life to live. There’s no second round.”

Given such major differences between the Canadian and American academic systems, do you think being a product of the American graduate system prepared you to eventually work as a professor here? Absolutely. I felt pretty sure that I wanted to teach, because I had enjoyed teaching art-based courses to children and young adults at the Winnipeg Art Gallery while doing my BFA.

I think of myself as more of an artist than strictly a photographer, and the same was true then. In school, I did a lot of painting and drawing, because I thought that I wanted to be a painter. But there was a lot of hesitancy around me going to art school. There was a strong ethos in my family about being able to make money, and my parents were concerned about my ability to support myself—my father in particular. He was an architect, but had wanted to be an artist. He said, “Look, you’ve got to be able to make a living. You don’t want to get into a situation where you go through college and have student debt that you can’t pay off, or to not be able to find gainful employment.”

He died in an accident during my first year of college. Obviously, that created a seismic upheaval. I spent the rest of that year and the next moving from interior design to architecture, thinking about how to channel a creative practice into something that would also have economic security. After trying architecture for two years, and hating aspects of it, I opted for art school. The sudden nature of my father’s death made me aware that there’s just one life to live. There’s no second round. With the positive experiences I had teaching kids, I also realized there was a possibility of supporting myself through teaching. Even though teaching jobs were hard to come by, I thought, I’ll try my damnedest! And if all else fails, I guess I can do dishes or wait tables or whatever it takes.

I got my BFA in 1986, and my MFA was a further commitment to being an artist and being able to seek out jobs at the university level. I needed that larger experience to develop as an artist and as a teacher. The activities of being an artist and an educator are interwoven; one informs the other. These are just two of the many roles I play, along with being a parent.

I can understand why maintaining the distinction between artist, photographer, and educator would be important. How do you balance your teaching commitments with your art practice? There’s no such thing as balance. (laughing)

Right? (laughing) It’s always much more topsy turvy than that. If I’m doing one thing, I’m neglecting 72 others. If you want to have a life and children, you have to juggle things. Even without children, you’re still juggling various demands, like your loved ones, pets, laundry, and rent.

I’m very fortunate to be a teacher at the University of Chicago. It’s a research institution, and we have a fantastic department with fantastic artists, theorists, and writers that are engaging and stimulating. I learn a lot being here. Even though we don’t always agree, there’s a lot of mutual respect. There have been years where teaching has been a lot of work, and in some ways it took away from my own practice. I think whatever it is you do, it all comes back; you just find a way of channeling it. I’m kind of monomaniacal about making sure that I keep up with my art making, and staying involved and invested. It’s imparative to maintaining an art career, but I don’t think I could call that ‘balance.’

It’s a term people throw around loosely, but I think very few actually totally achieve it. What are you currently looking at through your own research? I once asked one of my former professors—Tod Papageorge, who’s a great professor, critic, and artist—what he was influenced by. I thought he would talk about the other visual artists he was interested in, but he said that the things that often excite him the most aren’t visual. Instead, what moved him was literature, poetry, and episodes of Breaking Bad.

That really struck a chord with me, because I feel like I’ve been more influenced by writing, music, and other things more than I am by other photographers. Which isn’t to say that I don’t look at other photography. I find that reading, and the way writers use language, is important in my art-making.

“There wasn’t that sense [in Winnipeg] of Oh my god, this has to be great! It felt more like, Well, no one’s ever going to see this anyway, so what does it matter? I think that provided me with a lot of freedom.”

I definitely see that influence in your work. It reminds me somewhat of poetic experiments with language, where you’re disrupting the grammar and syntax just enough to throw the viewer a little off balance, or make them feel uncomfortable. Is that your intention? Absolutely. Photography and image making is so mired in advertising and selling, and always has been. We’re constantly marketed to through visual codes, where marriage and monogamy and all sorts of other societal norms get formulated and sold to us as the things we should desire. In my photographs, I want to “trouble” the image, and unsettle these directives. Like when you have a little thorn in your craw; it persists, rather than explodes. I’m interested in making images that are more propositional than dogmatic.

I remember traveling with students in China, where we were treated to a lecture by a well-known Chinese artist and art historian of contemporary Chinese art. Like most art schools, we usually have a 50/50 (or higher) women-to-male student ratio. But in this class, there were about 99 female students, and maybe one male student. Yet, when he was showing contemporary Chinese art, all of the artists he showed were male. I asked him, “You have a room full of students who are mostly women—why do you only show male artists?” And he said, “You know, I’d never thought about that, or noticed before! But I have an answer for you: Men’s work is more powerful, and has more vitality, whereas women’s work is more soft, and delicate.”

The presupposition is that work that’s authoritative and vigorous is good, and that work that’s tentative or propositional is bad.

Unbelievable. And whatever artwork women are making, they’re still up against this antiquated gatekeeping system that looks at and valuates the art from within that framework. Yes, the rubrics are set against us! There’s no way to win. It goes back to the French feminists talking about how language already presupposes what’s good and what’s bad, and how if you’re outside of that, you’re just never going to get in. I think about that a lot. As a teacher, it’s important to think about who’s supported, and to promote and consider numerous identity factors in order to foster an environment that calls our presuppositions into question.

Let’s go back for a moment to this tenuous space you often create in your photographs. I think of still lifes as depicting things that are already dead and inanimate. But there’s an unsettling kind of movement you create—like, that crystal glass is just about to fall off the edge of the table!—that makes me really nervous. Do you see this movement-making as a form of risk-taking, or even as a political act? I do, definitely. I’m trying to visually articulate that tenuousness you describe. The tenuousness of being a body, the fragility of making a life and a home, and the labor that’s involved in that—both ideological and practical.

Historically, that sense of something about to fall off of the table is a trope that’s been used since 17th century Dutch-Flemish still lifes all the way to the gorgeous still lifes of Irving Penn—including his Clinique ads. Because, as you note, the still life is usually made of objects that are inanimate. This picturing of potential motion is a means to animate the scene. It’s a way of creating a kind of narrative tension in the space that rubs against the inertness.

I’m also deeply intrigued by how the Dutch-Flemish still lifes of that time period came about, and how that mercantile society was an early-capitalist society that was suddenly very wealthy and didn’t have an ideological or philosophical system to absorb or appreciate that wealth. In Southern Europe, you had the Catholic Church. There wasn’t that same kind of ideology and religious set of ideas in the North. Instead, Protestantism promoted the idea that because God made everything, everything and everybody was equal. So, the description of a crust of bread was depicted as tenderly and exactingly as a crystal goblet. There was a real insistence on describing everything with great detail and accuracy.

Photography came about because it met a set of societal demands that began in this period—to create images that look like what we see with our eyes, and to tell us how we should see, what we should think about, what we should want, what we should aspire to, what a home looks like, how we should look, how we should love, how we should fuck—everything. They purported a kind of truth, and they were also able to be widely reproduced.

This notion of photographic accuracy and “truth” is really interesting. In your work, you often seem to juxtapose what’s “real,” with what isn’t, like candy fruits that you’ve given actual stems and leaves to, placed next to real figs and peaches. Do you feel at all like you’re setting up a new way of seeing for the viewer? I had this hilarious discussion with somebody who was looking at one of my post–2010 photographs, built from existing images. He said, “You know, I look at the photograph and make a distinction between the photograph of the grape that’s beside an actual grape, but then I realize that actually it’s a picture of a picture of a grape.” (laughing) It’s all just pictures.

Part of what I’m trying to speak to is the way that we come to know the world, which is through images. An apple is supposed to be this big, juicy, red apple-thing—whether it’s the Snow White apple, or the apple in The Garden of Eden. I remember going to the farmers market when I was a kid, and you’d get apples that had little worm holes, or were bruised, but you’d cut off the bruised bit and the apple tasted delicious. Now, we purchase things called “Delicious” apples, and you get these tomatoes that are all a uniform red, but they don’t really taste like anything.

There are YouTube videos teaching people how to cook food to be photographed for their Facebook page, vs. food they’re actually going to eat. We’ve gotten so used to choosing what something looks like, over what something tastes like. In giving ourselves over to our sense of vision, it’s as if we’re saying it’s the only sense that matters.

“There’s no such thing as balance. It’s always much more topsy turvy than that. If I’m doing one thing, I’m neglecting 72 others.”

We so often overlook what might otherwise be considered “ugly,” in favor of perfection. It brings to mind the wabi-sabi aesthetic, and how it prizes imperfection and impermanence. You tend to use organic material in your work that’s in various states of decay. What do you find so beautiful about decomposition and imperfection? I like to joke that I’m really bad at throwing flowers away, because I love what they look like throughout the process of decay. I think they’re so amazing, even though the water turns green, and the petals fall off. I leave them like that until everyone in my family says, “Get rid of those rotting flowers!”

I have a decaying bouquet in my kitchen right now! It’s a beautiful process. I totally get not wanting to throw them out. Yeah! It’s so beautiful.

I initially started the still life project in 1994, but it took me until 1997 to figure out how I was going to work. I had been reading Norman Bryson’s Looking at the Overlooked, as well as Roland Barthes, and thinking about the photograph as a kind of aftermath. Barthes describes the photograph as always and only after the fact; that its truth is only that it was then and there, that the moment described exists only as an image of what was.

Instead of inviting the viewer to partake in the traditional still life, I was interested in what remains. What gets left over, what you can’t get rid of, or what you try to hold onto. It’s almost like once you photograph something, you can then own it and forget about it. It’s this way of assuming you have knowledge of something, even though you don’t. You see that all the time, where people go to historic sites and they take a picture and walk away without even really looking at anything.

Oh, I know. Especially these days (thanks, Instagram). It’s as if they’re thinking, Okay! Got that one. Been there. Now I’m done! Even the way we describe the activity of taking a photograph involves acquisition. That fascinates me. Instead, I’ve tried to wrangle with the materiality of the photograph as a stain, as a reminder, or as residue.

Thinking about the small, and about how we live our lives, and about making do, has also been really important to me. When I started this project in the ‘90s, bigger was better. Photographers I love, as well as ones I’m not as fond of, were making really big prints. They had to have these really big, film-like crews and lots of expensive equipment. It was all so macho. I wondered, Is this what it takes to make a good photograph? What about what’s already around? Can small things be great?

Where are you gathering these small, everyday objects that you use in your photographs? And what exactly are you looking for when considering what to incorporate? It’s changed over time. I usually start by noticing the way objects fit together or speak to one another. Sometimes it’s about the way colors reverberate, or a particular kind of shape—formal kinds of things as much as the sentimental.

I’m a collector. I might talk about being a minimalist, but I do like things. Design Within Reach might meet the leftover dish from a friend or relative you simply can’t discard, along with a tchotchke your kid made that’s not your particular aesthetic, but you kept because of its sentimental value. In choosing things, it was first the stuff that was around me, because it was what I liked—whatever that means. It’s funny, we say things like, “I’m interested in this.” But what does that mean? That it makes me weak in the knees?

It’s about our obsessions, maybe. Yeah. When I was in Rome in 2001, I was obsessed with these jelly-fruit things. They make them in France, too. They’re basically fruits that are really concentrated with sugar, and they’re kind of jelly-ish and luminous. When light hits them, they glow as if they’re radiating light from the inside. It made me think about how the photograph is usually considered the processed thing, the cooked thing, the candy, the artificial. And the scene that’s being photographed is what’s natural, original, raw. But those dichotomies are so false. They don’t hold up, because we don’t even have fruit that’s natural.

As I continued with the still life project in 2006, I made a series called To Say It Isn’t So, where I photographed things that I found on the street between my house and my studio as well as things destined for the trash bin. I set myself the task of making still lifes out of those objects as a way of pushing past what I already knew.

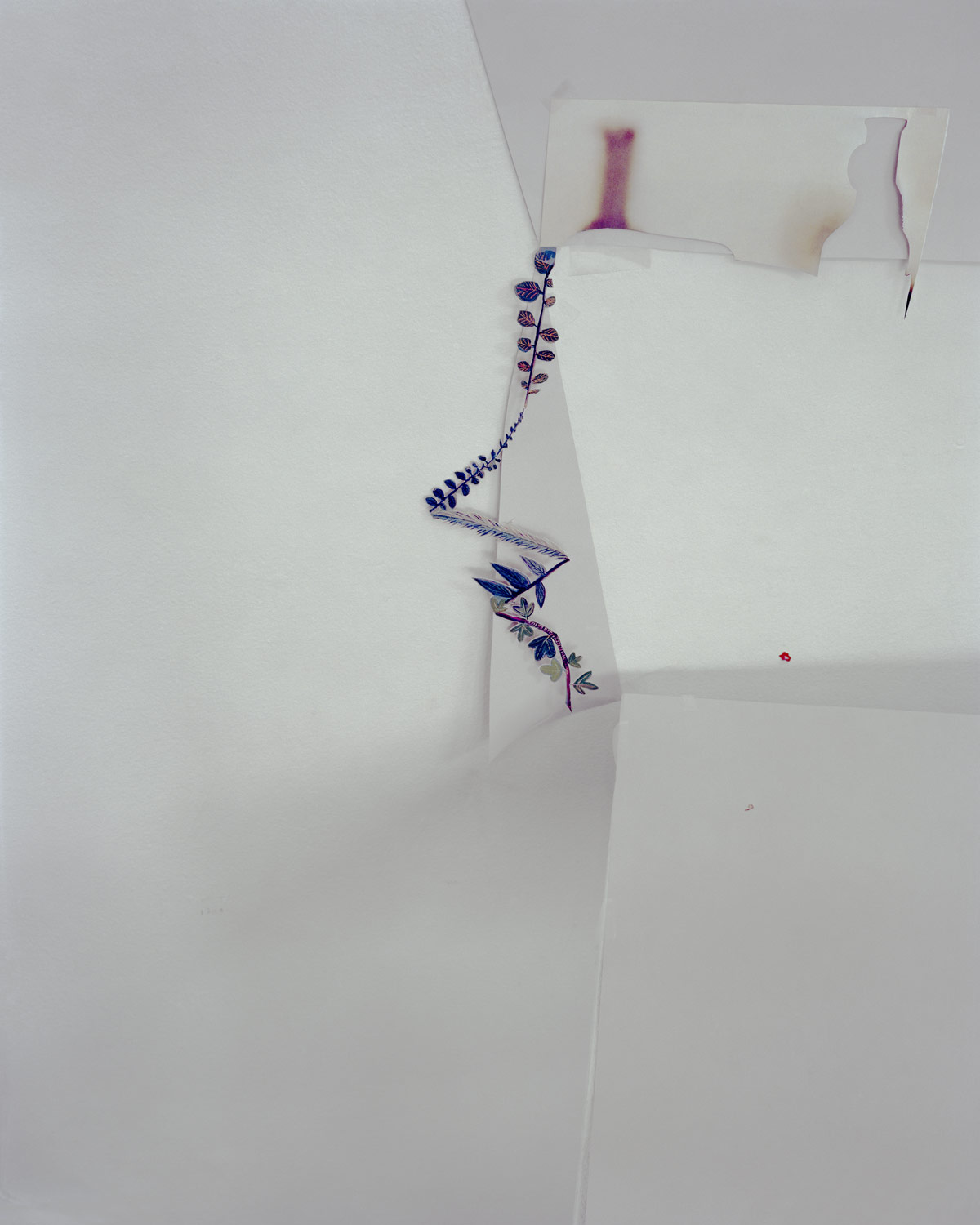

In 2010, after a year’s hiatus from making pictures, I started building still life scenes using others’ images. Rather than being flat, I would build a three-dimensional scene in front of my large-format camera, specifically for the purpose of photographing this set up. The idea being that if you walked into my studio, you would never see the resulting image, because the photograph is only accessible through the camera’s lens and the material of film and print.

Increasingly, I’ve realized that I let go of language and words when I’m in the studio. Instead, the dialogue is in the looking, the sensing.

“…marriage and monogamy and all sorts of other societal norms get formulated and sold to us as the things we should desire. I want to ‘trouble’ the image, and unsettle these directives.”

Do you see yourself continuing to further evolve this still life project? In this new work I’m making I feel like I’ve had to learn a whole new language. I’m just starting to kind of get a handle on it. I was in Berlin for six months, and it was a strange experience. I’ve been trying to shift the focus away from food, because while food is what’s pictured, the work isn’t about food. Thinking about food is to think about sustenance and want, need and desire, fullness and abstinence. I want to develop these elements in my more recent work.

I’ve also been drawing more from fashion, architecture and design, furniture and spaces. I’m using a huge array of resources. The pictures are still very strange to me; there are a lot of different, sometimes competing, elements that I’m trying to cohere, but just barely.

Putting yourself in that kind of vulnerable space—learning a new language, so to speak—also seems particularly tentative. Yes. It’s almost like I had to forget language. I’ve been working for two years now on trying to make these photographs. It’s been difficult to not rely on what I’ve already used in the past, because I don’t want to simply reproduce what I’ve already done, or what I already know. I also want to respond to changing conditions, with the proliferation of digital media and image circulation.

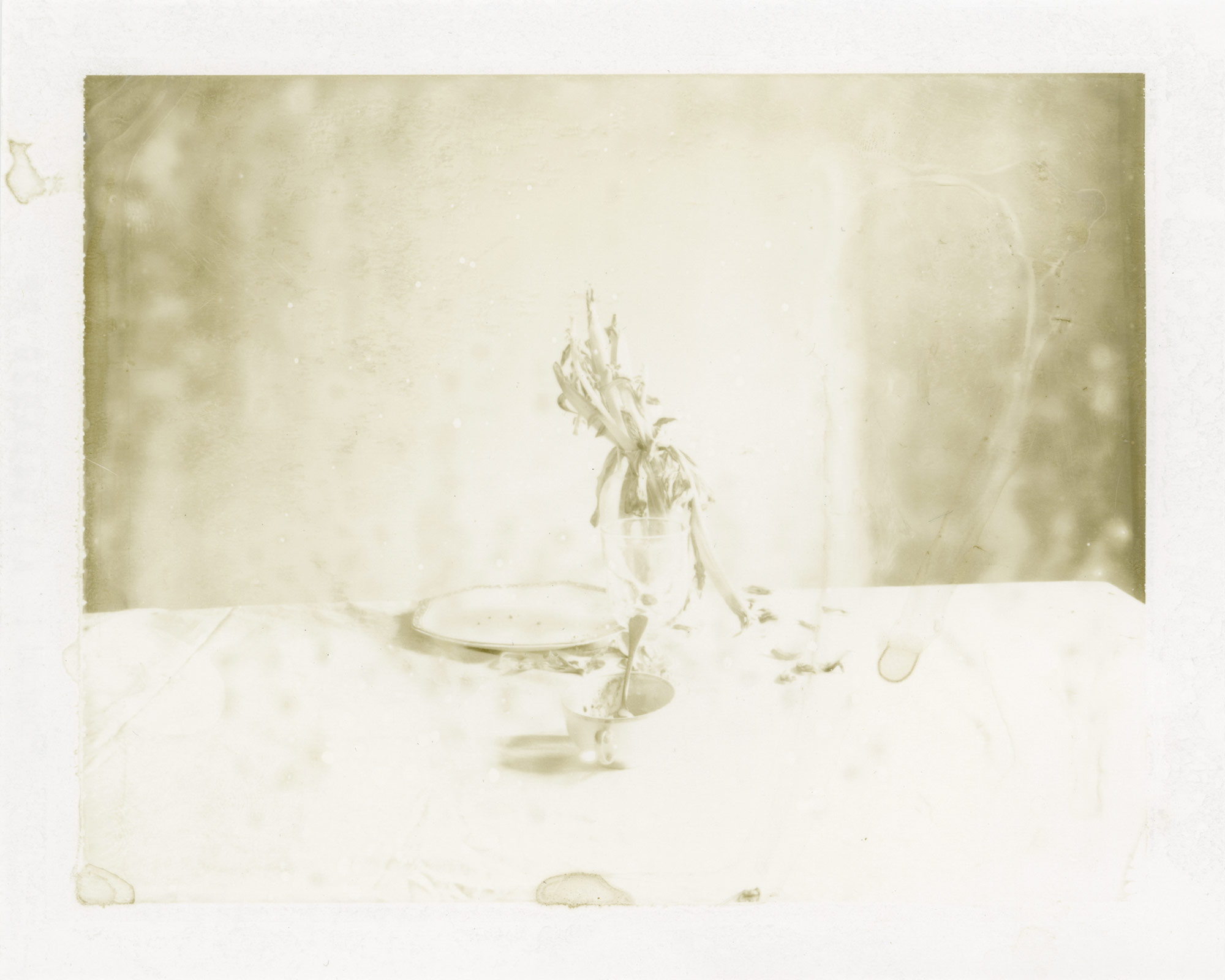

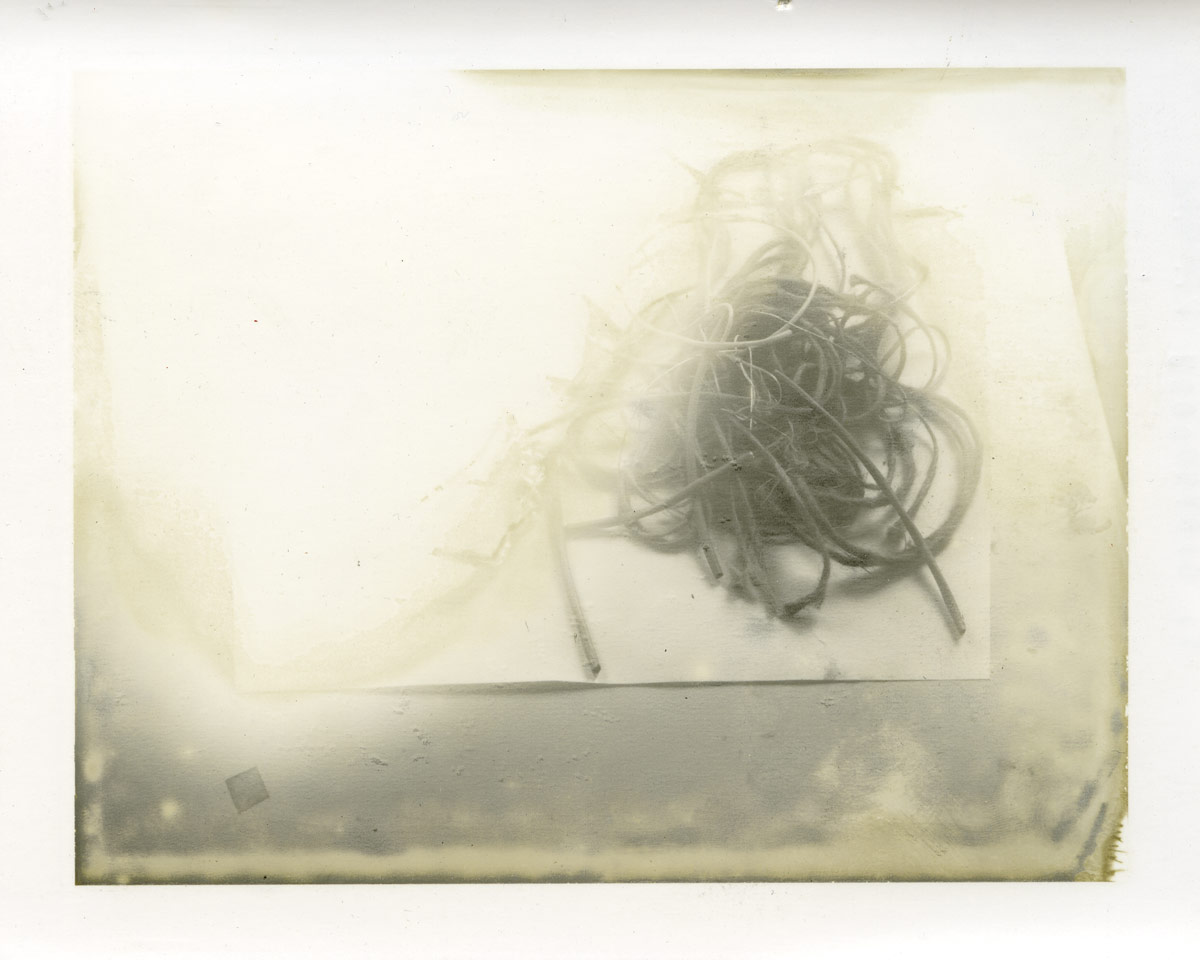

My new book, Time’s Assignation, is of old work—Type 55 black and white Polaroids I made between 1997 and 2007. They’re akin to sketches of the larger-scale work I made during those years. It’s an important set of images for me, and it’s been interesting to return to that work. In my acknowledgements, I described Lot’s wife looking back and being turned into a pillar of salt in order to discuss the dangers associated with getting fixed in the backward glance. When the photograph was an analog process, it used light sensitive salts, and I love this material connection between Lot’s wife and the photograph.

Not to get caught in the past, but do you feel creatively satisfied with the path you’ve chosen, and the work you’ve made up to this point? Overall, yes. I’m a very lucky person, and have numerous ways of enjoying myself—be it gardening, sewing, playing with my kids, and of course, making art. Even though the last two years have been difficult as I work through these photographs, I’ve been able to develop other work, including Molosco (a set of porcelain dinnerware), and two textile projects (Stain, and The Telephone Game) in collaboration with a fabulous artist, John Paul Morabito. Sometimes, it feels like falling in love, and at other times like groping around in the dark. Making art and being alive is a process, and I’m happy to be here.

“Sometimes, it feels like falling in love, and at other times like groping around in the dark. Making art and being alive is a process, and I’m happy to be here.”