- Interview by Tina Essmaker July 15, 2014

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Jonathan Harris

- artist

- designer

- programmer

Jonathan Harris is an artist and computer scientist whose work explores the relationship between humans and technology. Born in Vermont, he studied computer science and photography at Princeton University, and now lives in Brooklyn. He created the storytelling community, Cowbird, and many other projects, which have been exhibited worldwide. He loves to swim, walk, read, and obsess about the number 27.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I was born in Vermont, in a beautiful part of the world. My family lived on a farm overlooking Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains—the farm has been in my mom’s family since the 1800s, and it’s my favorite place in the world. I had an idyllic childhood in nature, playing outside and building forts in the woods. I loved it there, and I’d like to live there again someday.

When I was four, we moved to New York City so my sister and I could attend school here. My dad also had his business here, so we spent summers in Vermont and lived in New York for the rest of the year. I didn’t really like New York as a kid, so I retreated into my own imaginary worlds. I remember having two imaginary friends named Lulu and Big John, and I communicated with them using a little telephone cord. I plugged one end of the cord into a hole in the carpet and put the other end into my ear. They played out little dramas, which I told my parents about every night during dinner. When I got a bit older, I outgrew those imaginary friends and became interested in comic books instead. In my bedroom, I built forts made of pillows and sheets, and I hid inside them and read comics. Then I started inventing my own characters and made comics depicting their lives.

I was kind of a loner. I felt more comfortable in those imaginary worlds than I did in the real world. I was also a fairly sick kid. I had to wear electrodes on my nipples to monitor my heart rate until I was six years old because I had breathing problems. There were a few occasions when I stopped breathing entirely and had to be resuscitated.

Wow.

I had a pretty fragile early childhood. I had an operation to remove my tonsils and adenoids when I was six, which caused me to lose about 30% of my bodyweight: I only weighed around 35 pounds, and kids made fun of me. My health started to improve after that operation, but I think the introverted, outsider way of approaching the world had already been embedded in me.

When I was a teenager, I became interested in oil painting, and I filled sketchbooks with dead insects, plants, ticket stubs, drawings, and watercolor paintings. In my early 20s, I began to travel frequently, and my sketchbooks evolved into travel journals.

After high school, I attended Princeton University in New Jersey and studied computer science and photography. I was planning to study English or architecture, but I needed to take a computer science class to fulfill a requirement. It was a totally new subject for me. One of our first assignments was to build a simple homepage for ourselves and put something personal on it. I scanned in a couple of my oil paintings, complete with gold frames, and put them up on the site. I remember having a “Eureka!” moment when I realized I could send a URL around to people, providing a direct connection to my work. There had been no editor in the process, and I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission. I thought, “Wow, a lot of people are going to want to do this!” (laughing) At that moment, I decided to drop English and major in computer science instead.

Studying computer science was hard for me. I was pretty good at math, but compared to me, the other students in the program were like geniuses. Most of them had been programming since they were little kids, while the only computer experience I’d had before college was sending three emails to my water polo coach. For the first time in my life, I was getting C’s instead of A’s. It was hard, but I stuck with it. By the time I was a senior, we were able to do independent work, which allowed me to design my own projects. My thesis was a project called Extra! Extra!, which was basically an early version of Google News: it clustered international news articles so that readers could see different perspectives on the same story.

After graduating, I spent a couple of years feeling lost and confused. I started a travel magazine called Troubadour with some friends, but that didn’t work. Some other friends and I started a breath mint company called Oral Fixation Mints, but that didn’t work either. Two years after graduation, I was still living in Princeton, New Jersey, and I was generally feeling pretty bad about myself.

You stayed in Princeton to try and get something off the ground, but nothing was working?

Right. September 11th had just happened, so the advertising market and the economy in general was stalled. Eventually, I received a lifeline in the form of a fellowship to a place in Italy called Fabrica. It’s like an art residency program for people under 25. I was given a one-year fellowship to go live and work in a beautiful minimalist glass and concrete complex designed by the great Japanese architect Tadao Ando. It’s all funded by Benetton, so our housing was paid for and we received small stipends each month.

That sounds amazing.

It was amazing. There are typically around 50 people from 30 to 45 different countries: it’s incredibly diverse. It’s all nontraditional art, so there isn’t any painting or sculpture, but it includes graphic design, product design, photography, film, music, writing, and interaction design—which is what I did—with about 10 people in each department.

Fabrica was where I first started using computer code as an art medium. It was a place that gave me confidence in my work, which I hadn’t really had up until that point. That was in 2003, when I started making data-based works. The first one was a project called Word Count, which was just a simple data visualization of the 86,800 most frequently used English words, arranged side-by-side as a very long sentence, ranked and scaled to reflect their commonality. Then I made another project called 10 x 10, which automatically constructed a photo-mosaic of the world every hour, based on international news coverage at that moment.

That’s neat.

It was a simple project, but it was novel at the time. The whole idea of taking data from multiple sources and merging it together to create something new is common now, but back in 2004 nobody was doing that yet, so 10×10 really struck a chord. It was on CNN, and in lots of newspapers. I think the media is generally obsessed with itself, and since 10×10 was nominally about the news media, it received a lot of attention from the press.

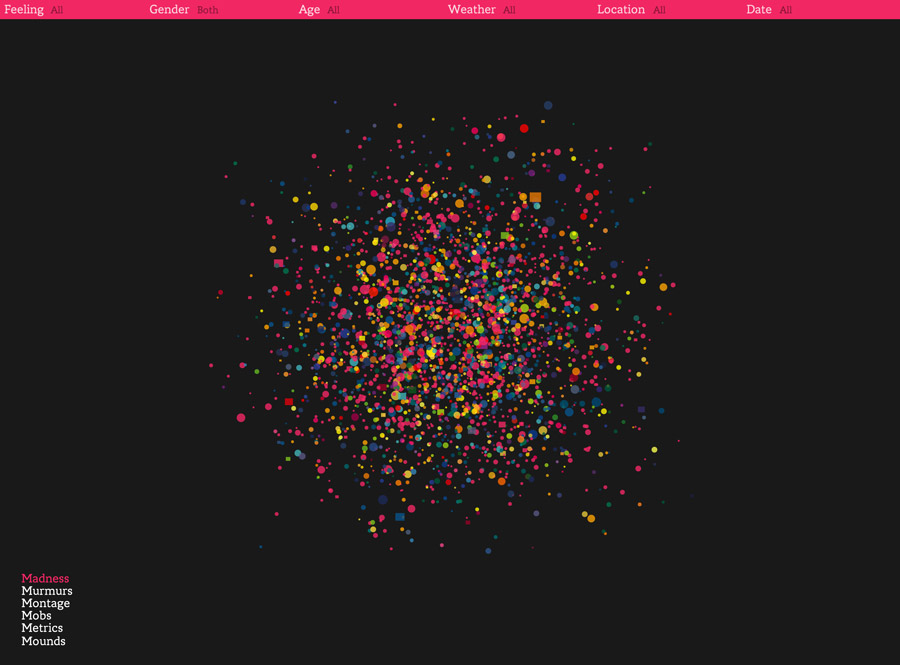

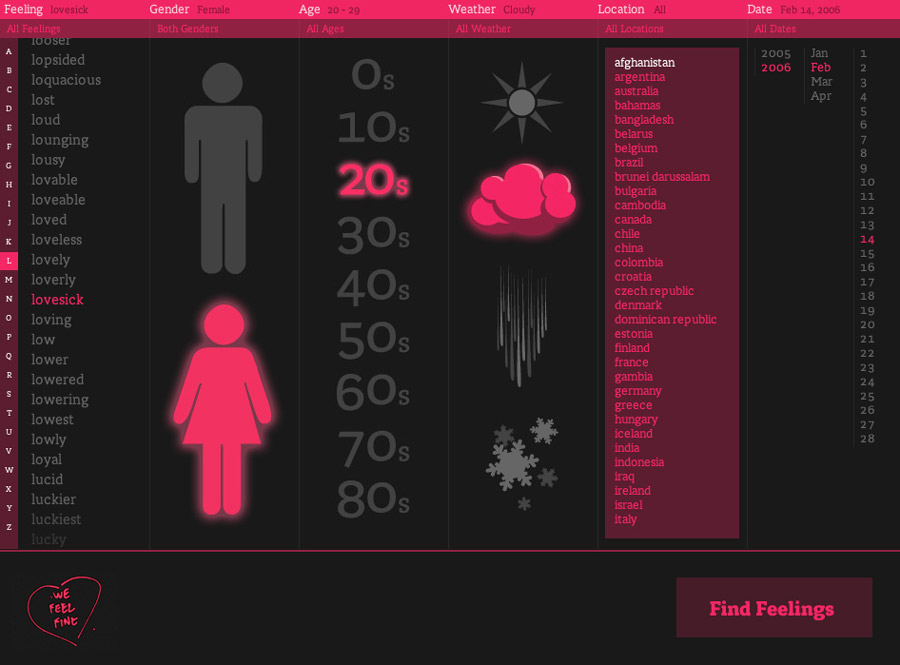

After finishing my residency at Fabrica, I moved to New York to take a job at an Internet news startup called Daylife. I stayed there for about a year and a half, and I worked on my own projects at night and on the weekends. I stayed up late, writing code for my own work, and that’s when I started doing projects like We Feel Fine, which is a search engine for feelings; Universe, which was a site that tried to come up with new constellations for the night sky based on international news; and I Want You To Want Me, which was an interactive installation for MoMA about online dating and people’s search for love on the Internet. Those were all data-based projects that involved looking at huge data sets, teasing out the stories hiding in them, and then presenting those stories in playful, interactive interfaces. I did that kind of work for five or six years.

Were you just putting that work out into the world and then receiving feedback? Or were people asking, “Can you do this project for us?”

Most of those projects were self-initiated, with the exception of I Want You To Want Me in 2008. Paola Antonelli, a curator at MoMA, liked some of my other projects and asked if I would make a new one for a show she was organizing.

A bit of advice I give to art students or younger people is this: You’ll become known for doing what you do. It’s a simple saying, but it’s true. When you do something, you will become known as the kind of person who does that particular thing. The only way to start being asked to do something you want to do is to start doing that thing on your own. Eventually, if you do it well, and long enough, people will start asking you to do it for them.

That was my approach for those projects at that time. I focused on finding a way to finish them, even if it meant working long hours, not sleeping much, and not having too much of a social life. However, I was eventually able to leave my day job and focus on those projects full-time.

I did that up until my mid–20s. In my late 20s, I wanted to get away from screens and go out into the world more, so I started designing projects that were more like documentaries or mini-adventures. I’d make myself go do something in the physical world, following certain rules that I made up—almost like a computer program. One of those projects was called The Whale Hunt, where I went up to Northern Alaska to spend 10 days with a family of Iñupiat Eskimos during their annual whale hunt. The idea was to create a photographic heartbeat of a 10-day experience: I took a photograph once every five minutes, and more frequently when my heartbeat increased. I produced 3,214 images, and when I got home, I built an interactive web environment that allowed people to choose different paths through the story.

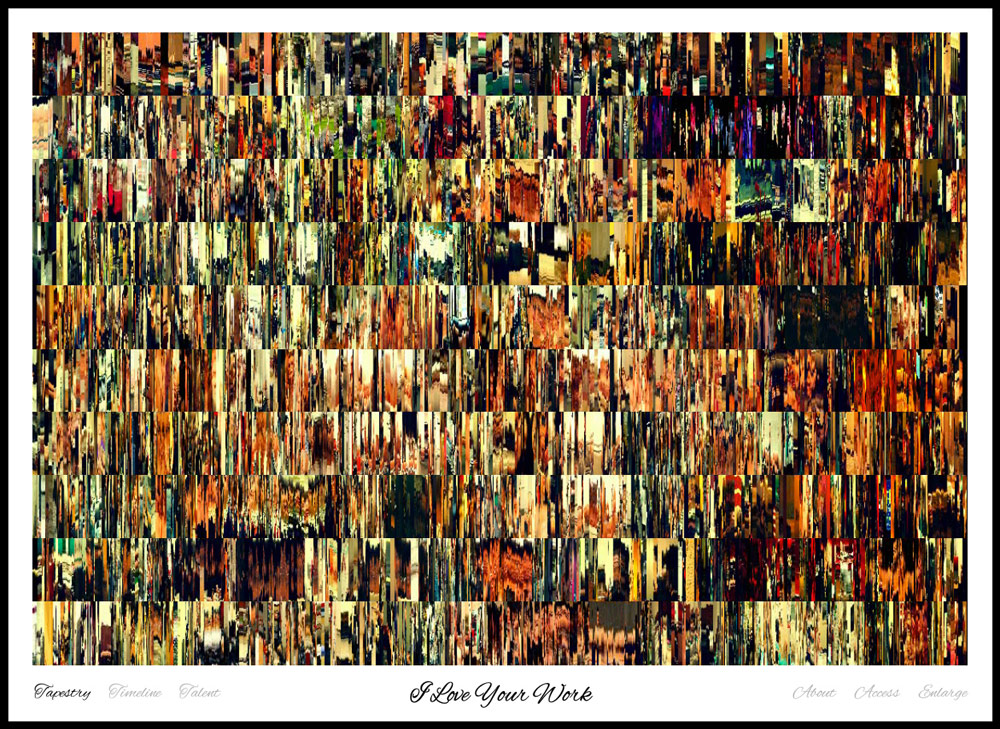

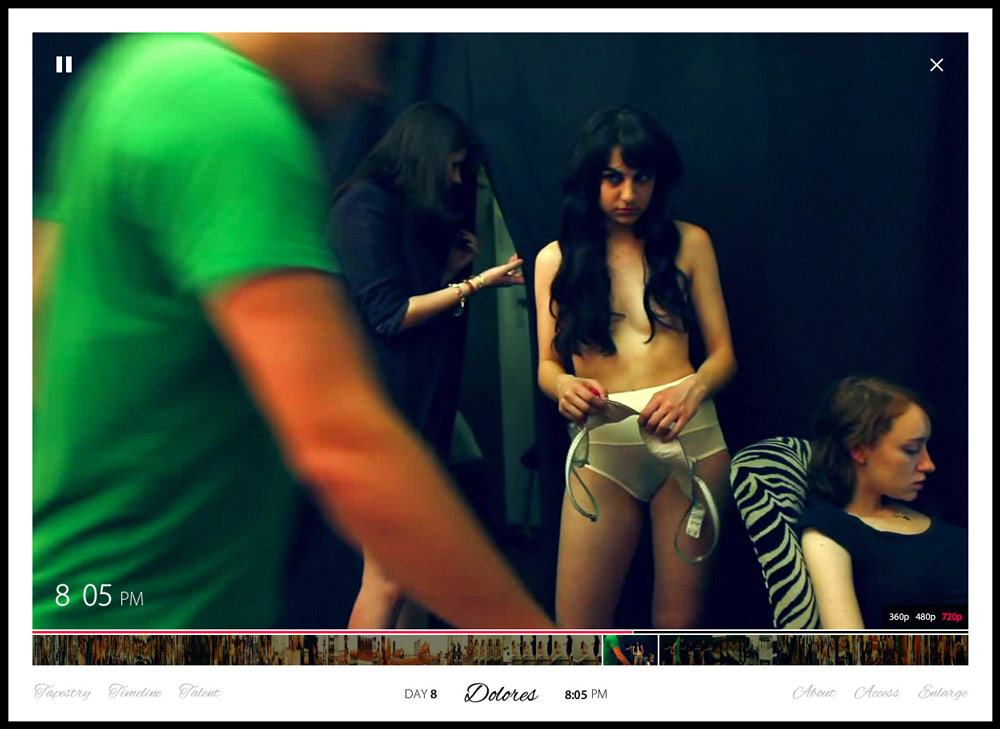

I did a few other similar projects. In 2009, I did a project called Balloons of Bhutan, where I went to the Himalayas and interviewed people about happiness and handed out balloons. In 2010, I did a project in New York called I Love Your Work, which was about filming the everyday lives of queer sex workers while they produced a lesbian porn series for the Internet. Every five minutes, I took a 10-second video clip of whatever was happening in their lives at that moment—little abstract glances into the realities of people who make fantasies.

The first phase of my work was the big data stuff, looking to the Internet for material, and then recycling that data back into itself to make something new. The second phase involved more real-world projects that ultimately went back to the screen, but which began with a real-world experience. I did that up until I turned 30, which is when I moved out of New York and kicked off a three-year period of hermetic living and solitude. I moved into a cabin in the woods of Oregon for few months, then went to live in New Mexico, Iceland, Vermont, and Northern California.

What was your intention behind doing that?

I felt pretty overloaded on New York City and being around all of these smart, fashionable people. I just wanted to get back to basics. I was feeling a little disconnected from who I was as a person and what my life was all about. I had gotten carried along in a tidal wave of cocktail parties, getting on flights, going to conferences, and doing one project after another. I think I wanted to stop all of that for a while and have a little space and silence.

During that phase, I started taking a photo and writing a short story every day, which I started on my 30th birthday. I did that for about a year and a half—440 days in all. Having that daily outlet for self-expression was a good companion throughout that time of solitude. When I stopped the daily photos, my friend, Scott Thrift, visited me in Vermont and made a short film about the project, which I think communicates it well.

Throughout that time, I was also building Cowbird, which is a storytelling platform that allows other people to conduct similar rituals themselves.

Were you doing any paid work during that time?

Not really. I had saved up enough money from my previous day job, and I knew I could coast for a year or so.

In 2007, I gave a TED talk, after which I started receiving invitations to speak at companies and conferences around the world. I found that to be a great way to earn a living because it was such a small time commitment that allowed a lot of extra time to make work.

That’s primarily how I’ve been supporting myself since then. I don’t make a lot of money from it, but it’s generally enough to support my life, give me free time, and pay my rent. Recently, I’ve been wanting to experiment with finding sponsors for projects. It’s something I haven’t tried yet, but I think it could be interesting, given the right match.

The Cowbird project also generates a little money from paid members. It’s a free service, but there’s an optional premium package that people can sign up for called “citizenship.”

How have people responded to the recent Cowbird redesign?*

It’s been interesting. It’s not a new project anymore, so it wasn’t really a newsworthy event. We didn’t get much in the way of press or media attention, but the feedback we’ve been getting from the people who actually use Cowbird has been uniformly terrific—people really seem to love it.

I’ve tried to set up Cowbird to be a timeless project, as opposed to a timely project. Cowbird tries to encourage a deeper, more personal, longer lasting kind of self-expression than you’re likely to find anywhere else on the Internet. It doesn’t necessarily follow all of the latest design trends, but hopefully it’s a space that can last for many years.

We feel like that about our content, too. I hope that in 10 years someone can read one of our interviews and still get something out of it.

Where does the name The Great Discontent come from?

It actually came from a conversation that Ryan and I had with one of our mentors back in Michigan. He told us: “You need to learn to be content in your discontent. You will always be restless.” Discontent can be negative, but it can also be positive. It pushes us to continue to making, even though we know we’ll never reach complete contentment. But that’s okay.

That’s great. Right now, I feel like a chapter has ended and I’m not totally sure what the next chapter will be. But I’m trying to embrace it and be content with that. (laughing)

“Right now, I feel like a chapter has ended and I’m not totally sure what the next chapter will be. But I’m trying to embrace it and be content with that.”

Have you had any “Aha!” moments when you realized what you wanted to focus on?

The first one was probably seeing how radical it felt to have a personal homepage in 1998. Since then, the medium of code has felt like the most appropriate medium to express the times in which we live. It communicates the speed, complexity, and interconnectedness of everything around us, but it also expresses the beautiful patterns that can emerge from that chaos. Code is an elegant way of approaching all of that, which I think is more difficult to approach through older mediums like oil painting or sculpture.

I frequently struggle with my relationship to coding. I’m not someone who adores the process of coding, but there is something about it that can be beautiful. Life is very messy and chaotic, but when you’re building a computer program, if it’s designed well and if you’re the only one working on it, it’s neither messy nor chaotic: it’s incredibly orderly. You know where everything goes and you can obsess over every little detail, so you can live in this perfect, imaginary universe. It’s kind of like the ultimate expression of my childhood impulse of hiding under a sheet fort and reading comic books all day. Code allows that on a much bigger level, where you can engineer a reality and then live within that reality for most of your days. That reality can be free of conflict, free of complexity and emotions, and I think there’s something appealing to a lot of coders about disappearing into such a space. It’s very utopian.

It’s a highly controlled environment, too.

It is. But there is another part of me that recognizes how alienating that process can be when it comes to being in relationships with other human beings, connecting with other people, and even being genuinely awake to nature and to the world happening around you. When you’re living in your head, in these abstract, constructed realities of code, they don’t always map onto physical reality in a good way. That can be a little tricky sometimes, and I’ve found myself ping-ponging between two modes of existing: one is living in the perfect abstraction, and the other is living in the imperfect reality. Neither of them feel complete, so I’m constantly moving back and forth between them. I definitely have a love-hate relationship with code.

Were there any other moments when you felt connected to what you might do in the future?

There were moments when I was working on some of my earlier projects—the ones that involved gathering data from the Internet, aggregating it together, and spitting it back out—where I felt like I was glimpsing the human species as a whole for the first time instead of looking at static maps, charts, and statistics as you do in places like The Economist. I felt like I was actually perceiving the pulsing humanity of the human species: the thinking, feeling, and expressing that’s happening around us all of the time. Somehow, through those big data projects, I felt like I was starting to perceive the dynamics of the human meta-organism.

Since then, I’ve started to see our species in those terms as one organism in which we’re each like little cells. We’re all living our own lives and caught up in our own dramas—all of which are totally valid—but there is also another scale of life that’s happening, which is the scale of our planet and all of our consciousnesses together. That idea is particularly interesting to me now, and that perspective really came to me through my work in computer science. And it’s since been echoed and confirmed by more recent readings of Zen philosophy, quantum physics, and various other sacred and mystical texts.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

I’ve never had a single mentor who I’ve repeatedly consulted with over the course of many years, and that’s something I regret.

In lieu of someone like that, I’ve had a number of smaller, short-term mentors. In college, I had a photography teacher named Emmet Gowin. He’s retired and in his 70s now, but he’s one of the most beautiful human beings I’ve ever known. Like all great teachers, he was not so much a teacher of his subject as he was a teacher of life; he used photography as a trick to talk about life. Emmet has this incredibly gentle, present, and awake way about him. To me, he seemed to demonstrate how complete a human life can be. As a human being, he was like a lighthouse for me.

Then I had a mentor in Italy when I was working at Fabrica. Sadly, he died a couple of years ago. He was a tall British man with very big ears and very big feet, and his name was Andy Cameron. He taught me a number of things, but there’s one lesson in particular that really stuck with me. When I’d been at Fabrica for about three weeks, I’d been compiling numerous ideas for projects in my notebooks. I was excited to meet with Andy, to tell him about all of these ideas, and to get his feedback. I told him my ideas for about 15 minutes, but he didn’t say much. When I asked him what he thought, he replied: “Jonathan, when you’re thinking of a new idea, ask yourself if it’s something the Italian everyman could understand.” I asked him what he meant. He said, “You know those old Italian men who gather on Sundays in Piazza Signori in Treviso, wearing their top hats and suits? If you can go up to one of those men and, in your bad Italian, communicate your idea—and if he can understand your idea, respond to it, and think it’s interesting—then you’ve almost certainly hit on something strong and universal. If you can’t do that, then you may have hit on something strong and universal, but your chances are a little bit lower.”

That simple insight from Andy caused me to rethink how I was approaching everything. From that point on, I tried to reframe what I wanted to do in less complicated ways. A lot of the ideas I had been proposing to him had been too clever for their own good: they were “inside baseball” ideas. Since then, every project I’ve worked on has been expressible in a single sentence. The sentence is typically something that emerges early in the process. For instance, with We Feel Fine, the sentence was: “A search engine for human emotions.” With 10 x 10, it was: “Hourly snapshots of life on earth.” With Cowbird: “A public library of human experience.”

Even though the design process can take months or years and lead me down many different pathways, once that sentence is found, it is sacred and shouldn’t be changed. Every design solution I come up with has to be checked against that sentence to see if it’s consistent: if it isn’t, I should throw it away. Those sentences are like the soul of each project. That way, when one of those Italian guys walks up and asks, (in an Italian accent) “What are you working on?” I can say, “I’m building a public library of human experience!” (laughing) Hopefully he would reply, “Ah! It’s beautiful! It’s lovely!” I think it’s a helpful rule, especially for young designers just starting out.

“…code has felt like the most appropriate medium to express the times in which we live. It communicates the speed, complexity, and interconnectedness of everything around us, but it also expresses the beautiful patterns that can emerge from that chaos.”

It’s also good advice for the web and tech world where we do have a tendency to make things overly complicated. Paring a project down to a single sentence would help us to better explain our work to friends and family. Speaking of family, are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

My friends are supportive, and my family basically is, but I don’t think they entirely understand what I do. My family doesn’t exactly disapprove of what I’m doing, but there’s a bit of a glazed-over look on their faces when I tell them about it. When my projects get press or are shown in museums, I think they appreciate them more. It’s become better with time: they understand more now than they did five years ago. They’ve also accepted that I’m taking this weird path through life, and it’s not always clear what the next step will be, but somehow it tends to work out in the end. And I think they’re okay with that.

Has there been a point when you’ve decided to take a big risk to move forward?

There have been a few. Quitting my day job and deciding to focus on my work full-time in 2007 was a big risk. Leaving New York and embracing a hermetic existence for a couple of years was a huge life change, but it felt like the right thing for my spirit. (laughing)

Did you have plans to come back to New York?

No, I didn’t. I remember driving out of New York on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in my U-Haul truck and seeing other people in cars waving at me, honking wildly, and giving me the thumbs up.

For leaving?

Yeah! Leaving New York is clearly an aspiration that many New Yorkers have. They want to get out of here, but for one reason or another, they end up staying. When they see someone leaving, something wakes up inside of them and they think, “Oh, yeah, that’s right. I want to do that, too.” I was surprised by that, but I remember thinking, “I have finally extracted myself and I’m never coming back.” But I ended up moving back three and a half years later, and I’ve been here about a year and a half this time around.

Did you come back for work?

No, I felt like the vagabond existence had run its course. I had lived in all of these spectacular, but highly remote and isolated places. The last one was a foggy and desolate beach cove in Northern California that was only accessible by descending a 300-step staircase down the side of a cliff—I had to carry my groceries down in a backpack. There were about 10 little bungalows that had been built down on the beach in the early 1900s, and I lived down there for a year and a half.

That’s pretty cool.

It was, and I felt blessed to live there, but it ended up making me feel cut off from the rest of the world. I felt like it was time to come back and be closer to my friends and family, people who I actually had relationships with. I wanted to stop running away and stop continuously seeking something more remote and spectacular. I was feeling the desire to have a home, with cups and plates and regularity. (laughing)

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Definitely. The kinds of projects I’m drawn to working on are projects that have some kind of usefulness to them—if not a direct utility, then some way in which they help other people in the process of living. I love the idea of gift-giving, and I like to think of the projects I make as little gifts for the world that somehow carry a seed that other people can use.

That’s been important to me, but in terms of directly improving the world, I don’t try to do that. When you try to solve a problem by introducing something new, what you actually end up doing is changing the system in which the problem exists. You may “solve” the problem you set out to solve, but in doing so, you invariably introduce new problems. You can’t just change things; you make things more complex, which increases both the good and bad parts of the system. That’s the way of life.

Instead, I try to make things that can wake up something in me or in others. I think most true solutions are internal and have more to do with changing individual perception than with changing external reality.

I think of my work as a kind of medicine. I look at where the world or society appears to be, and I try to design little medicines that go in and transform people in subtle ways. That’s tricky, though, because the world is always changing: the appropriate medicine in 2014 is different from the appropriate medicine in 2010. You have to stay alert to what you perceive to be happening around you to know what kind of medicine is appropriate.

Medicines can expire, too. For instance, the Cowbird medicine felt appropriate in 2009—it was designed to counteract a few predominant trends of the time. First, content was becoming shorter and shorter, but that’s actually a trend that predates the Internet and goes all the way back through the history of communication. Self-expression becomes more and more compressed over time: from novels, to plays, to poems, to letters, to phone calls, to faxes, to emails, to chats, to texts, to tweets. Each of these mediums is shorter than its predecessor, but it seemed like we were approaching a terminal velocity—what is shorter than a tweet?—and that a bounce-back effect was about to occur, with people suddenly craving more substance and depth.

Second, people were increasingly trading self-expression for self-promotion, turning their lives into ads in competition with the lives of their friends to see whose life could appear to be the most successful and interesting. This strange kind of interpersonal capitalism manifested itself through all kinds of metrics: comments, likes, retweets, reblogs, friend counts, and followers. Increasingly, people were treating their lives like products to be advertised and marketed to others. Cowbird was a medicine designed to counteract these trends. Instead of creating another shorter, faster format, it was designed to be slower, deeper, and longer lasting. Instead of helping people seem cool, it helped people be vulnerable—and on Cowbird, strangely, vulnerability became the primary currency: “How vulnerable can you be through your stories?” That medicine seemed appropriate back then.

Now, what’s appropriate is probably different. People are addicted to screens: we spend much of our time entranced by glowing rectangles. Maybe what’s needed now is to help people reclaim their attention, and to help them realize that their attention is a precious and finite natural resource that’s being pillaged and monopolized by technology companies whose products are designed to be addictive. Maybe it’s not about designing better experiences, but about waking people up to the value of their own attention, and letting them make their own choices about what to do, without manipulation. That’s a different kind of medicine than the medicine of 2009. I think that people will soon realize the value of their attention and start to reclaim it, and by 2017, some other kind of medicine will be needed.

Are you creatively satisfied?

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed that while I don’t necessarily feel less creative, I do feel less like the idea machine I used to be in my early 20s. Back then, I came up with one thing after another, and I had the energy to stay up until 3am every night producing work. That’s definitely changed now, and I have talked to a few friends who’ve have had similar experiences with aging. I’m not sure whether I have fewer good ideas or I’m just more selective about the ones I actually want to execute. It certainly feels different, and sometimes I worry that I’ve lost an edge that I once had. However, the types of subjects that interest me now are probably a bit deeper than the ones that interested me when I was 24.

I’m now 34 and it’s a funny time in life: you’re no longer the precocious young kid, but you’re not yet the wise elder, so it leaves you in a kind of strange middle ground. Most people take a break in their careers to raise kids and build homes and so on, but since I’m not currently doing either of those things, it leaves me with extra time to wonder about the appropriate way to behave creatively. It’s no longer about saying: “Look at me! Look at this cool thing I did! Look how neat and novel it is!” I feel like I’m past that now; that’s more of something you do in your 20s. At this age, you start to have a sense of what your life is like, what your relationships are like, and what the world has and does not have. Given all of that knowledge, I think you have to figure out what the appropriate response is. In terms of being creatively fulfilled, maybe I’m not in the sense that I haven’t totally understood what the appropriate response is right at this moment. I guess I’m still searching for that, even though I have a few hunches.

Earlier you mentioned feeling like you’re at the closing of a chapter, the start of something new. Is there anything you’d like to pursue or explore in the next 5 or 10 years?

For my whole life, I’ve dreamed of moving back to my family’s farm in Vermont. We have an old barn from the 1950s that’s standing empty, and I’d love to convert it into a studio space that can house myself and some other people, too, whether we’re working together or independently. I’d like to find a path to a place where I’m doing the kind of work that would be appropriate to do in a barn in Vermont (laughing), something that could be a rallying cry for others who want to do similar work. I’m not exactly sure what the nature of that work will be, but that’s one of my litmus tests for ideas nowadays.

I’d also love to design and build my own house. I took a house-building course last fall to learn the basics. Those are both long-term goals for the next few years.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

I think every artist or creator needs to figure out what is unique to them and then work from there. A good starting place for discovering that is looking at your obsessions and trying to embrace them. For instance, I’m an obsessive person: I’m extremely organized and analytical, and my apartment is neat and orderly. There’s a history in my mom’s family of people who are highly organized collectors of objects. My great grandmother started a place in our hometown called the Shelburne Museum, which is a museum of American folk art. She traveled around and collected things that everyone else considered to be junk. There’s an entire building of anvils, labeled and classified so you can see the evolution of anvil design over the years. There’s another building full of tea cups, and another full of quilts.

I’ve tried to embrace this obsessive, cataloging, organizing, labeling impulse that seems to exist in my family. I’ve channeled it in my own way through working with data, then sorting and analyzing and classifying the data. This obsessiveness is an impulse that could be destructive: I could easily become OCD, try to control everything in my life, and be freaked out by spontaneity. On the other hand, I can channel that impulse in a productive way that enables me to do things that would be extremely tiresome for others to do. Everybody has obsessions, and the nice thing about obsessions is that they give you an innate advantage regarding certain activities, because others wouldn’t want to do those things.

I like that. We sometimes tend to resist what we’re naturally interested in or good at, either because we think we should do something else, or because we don’t think it has a practical application in our careers or lives. But I have met people who have turned obsessions into careers, and who have found a way to support themselves by doing so.

As I said earlier, I’ve started to see our species as one organism. You can look at that from a metaphorical standpoint in terms of the Internet and all of us being users and blah, blah, blah; or you can look at it from a more mystical or spiritual standpoint. If you read into Zen philosophy or any mystical tradition, they all basically point to the same idea: there’s just one consciousness and we’re all expressions of it, and everything is connected because it’s all emerging from the same source.

If you accept that premise, then one way of seeing every human being, animal, tree, or anything else in our world is as a specific expression of a more fundamental universal consciousness. Each of those expressions—each human, plant, or animal—has something unique to it. The way the whole entity can become more conscious is for each of those expressions to embrace what they do uniquely. People should embrace their obsessions because that’s what they’re naturally programmed to do in this world.

How does living in Brooklyn impact your creativity or the work that you do?

I think it actually impacts my creativity in a negative way. Whenever I want to think clearly about something, come up with an idea, or make a choice about whether or not to do something, I leave Brooklyn and go to nature where I can be alone. Yesterday I was out in the Rockaways, pacing the beach by myself; there, I found it easier to think clearly about the appropriate responses to some different dilemmas I’m currently facing in my life. As a sensitive person in a city—and maybe a lot of creative people are like this—you end up being pulled in so many different directions and stimulated so much that you’re not even sure if the choices you’re making are your choices. Maybe they’re being colored by something you read or saw, or some sense of insufficiency or insecurity you have. The more you can create emptiness and silence for yourself, the more clear and personally appropriate your choices will end up being. In that sense, living in New York can have a negative effect on my ability to make something original: everything ends up being a reaction to something else.

Is it important for you to be a part of a creative community, or a community of people in general?

It’s important to me to be a part of a community, but not necessarily a creative community. For whatever reason, very few of my friends are artists—they tend to run startup companies, restaurants, or other independent businesses. I just recently moved into a new studio space at Pioneer Works in Red Hook, which is a creative community of artists and scientists, and it’s been good so far.

“As a sensitive person in a city…you end up being pulled in so many different directions and stimulated so much that you’re not even sure if the choices you’re making are your choices…The more you can create emptiness and silence for yourself, the more clear and personally appropriate your choices will end up being. ”

What does a typical day look like for you?

I’m a fairly structured person, so my days tend to be structured, too. I wake up around 7am, walk to the pool, swim for about an hour, then walk home and make breakfast—usually granola, yogurt, blueberries, and coffee. Then I work through the morning as late as I can before I begin to die of hunger. (laughing) The morning is my most productive time, so I try to prolong it. I eat lunch as late as possible because after that, I usually take an hour-long nap, go for a walk around my neighborhood, and sometimes get a second cup of coffee. I don’t come home and start working again until 3:30 or 4pm. I try to continue working until 8:30pm or so, then take a break to make dinner or go out to meet friends or something. Afterwards, I usually read for a while and then go to bed around 11:30pm. It varies a bit, but that’s a pretty typical day for me.

What music are you into right now?

I typically prefer silence when I’m working, but I’ve recently been obsessed with Renaissance polyphony music, where many different voices combine together into complex arrangements. I went to see Janet Cardiff’s sound installation, The Forty Part Motet at The Cloisters a few months ago, and it was one of the most beautiful experiences. I was listening to a lot of that type of music for a while, peppered with some Keith Jarrett, James Blake, Nico Muhly, Fever Ray, Godspeed You Black Emperor, and Bob Dylan, who is my all-time favorite.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

I’ve never been a huge TV fan, but I love movies. One of my favorite movies, which I actually saw three different times in the theater, is The Great Beauty. It won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film this year. It’s an Italian movie about a man in his late 60s, who wrote a great novel in his mid–20s. He hasn’t done anything much since then, except be a socialite around Rome, so he begins contemplating his mortality and the meaning of creativity. I really love it, and I think it’s a masterpiece and a complete inspiration for how to live.

I also love Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice, and Alejandro Jodorosky’s The Holy Mountain.

Do you have any favorite books?

I love The Way of Zen by Alan Watts and Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki. Both are good introductions to Zen. I also really enjoyed a book called An Intimate History of Humanity by Theodore Zeldin, which is about human nature though history and how we keep repeating the same behavioral patterns from culture to culture, over the centuries. Another book I love is Tiny Beautiful Things by Cheryl Strayed.

I love that book!

I think it’s like a contemporary Bible. It’s packed with life wisdom and insights about how to behave in different situations. When I read it, I was going through a painful breakup and driving across the country. I remember tearing up four or five times while reading it on a sofa in Telluride, Colorado.

If I could buy one book and give it out to people on the street, it would be that one.

Yeah, it’s great. I also recently bought a collection of books on haiku written in the 1940s by R.H. Blyth, who was the first Western scholar of haiku. They’re beautiful books that I like to read at night.

Do you have a favorite food?

My favorite food in New York is from a Chinese restaurant called Grand Sichuan International, which is on 24th Street and 9th Avenue. My favorite dish there is the Aui Zhou Spicy Chicken, which I like to order with sautéed pea shoots and garlic. It’s unbelievable—I dream about it. I also love duck confit and French food.

Last question: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

To have made the world a little more beautiful.