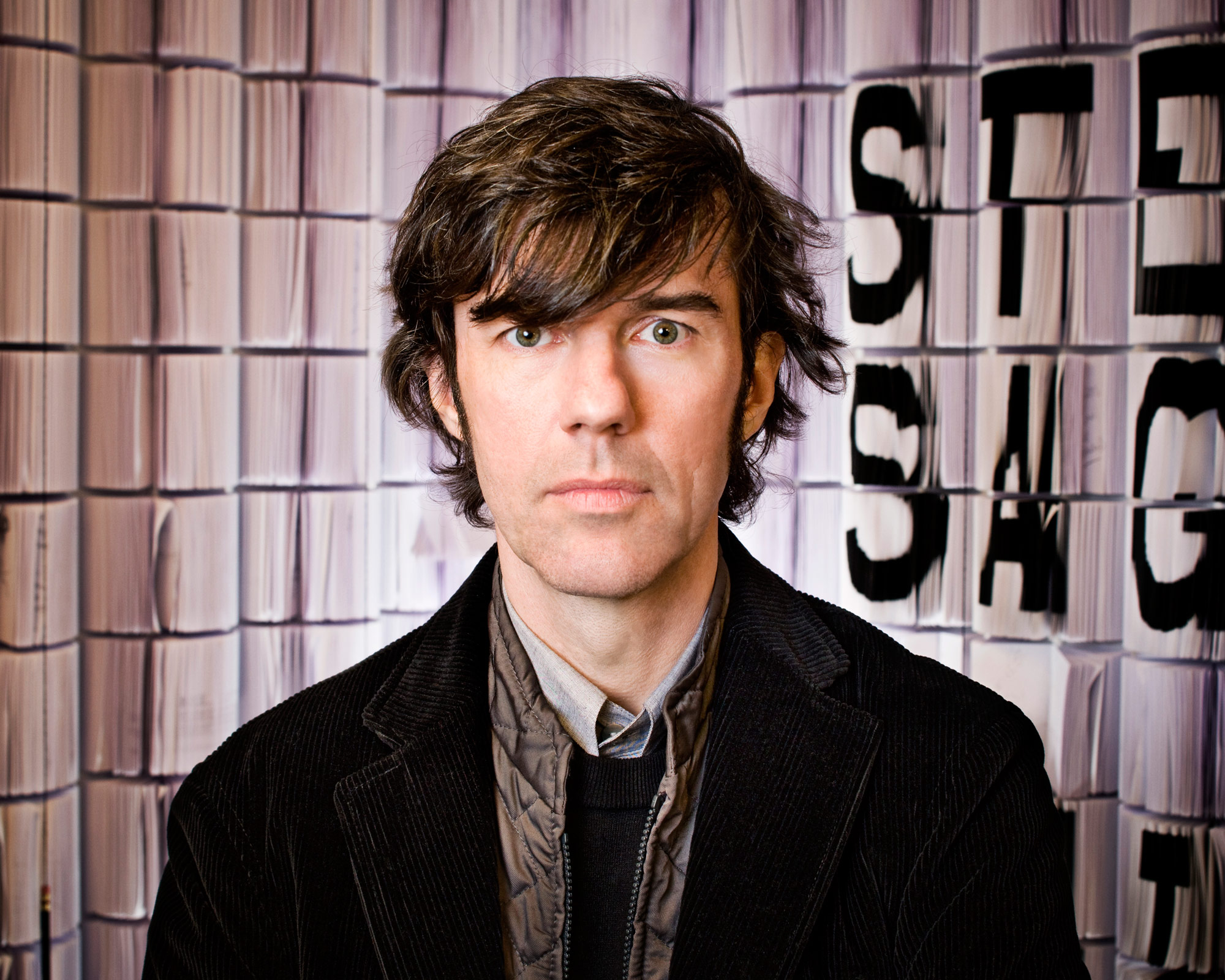

- Interview by Tina Essmaker June 23, 2014

- Photo by John Madere

Stefan Sagmeister

- designer

- entrepreneur

Austria native, Stefan Sagmeister formed the New York-based Sagmeister Inc. in 1993 and has designed for clients as diverse as The Rolling Stones, HBO, and the Guggenheim. He received his MFA from the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and a Master’s from Pratt. Stefan has exhibited work around the world, teaches in the graduate department at SVA, and lectures extensively. In 2012, Jessica Walsh became a partner and the company was renamed to Sagmeister & Walsh.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Three, available in our online shop.

Editor’s note: An updated version of this interview, including new images and work, is featured in print in The Great Discontent, Issue Three, available in our online shop.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

Well, my name is Stefan Sagmeister. I’m an Austrian designer who lives and works in New York City. I got to be interested in design when I was 14 or 15. I started to work for a little local magazine, but I quickly found out that I preferred the design part much more than the writing. At the same time, I played in bands that were not very good, which led me to became interested in album covers. That set the trajectory for me to apply to design school later on, when I was 18.

I did not get into design school, so I attended a small, private art school for a year and reapplied to the University of Applied Arts Vienna, where I then studied for four years. From there, I received a scholarship to study here in New York at Pratt Institute. I got a Master’s degree and worked for a year or so under the mantle of work-study. Then I had to go back because that scholarship came with a two-year home residency requirement.

I went back to Vienna for a year, then spent two years in Hong Kong, which was probably the most commercial time of my life. I worked under the mantle of a large advertising agency and opened a design studio for them. Through that, I learned everything there is about running a design studio; we worked for some of the agency’s very large clients and some of our own, much smaller clients within that construct. Then I came back to New York, worked for my hero, Tibor Kalman, for half a year, and opened my own studio.

When I started it, the idea behind the studio was to design for the music industry and to stay small. The first became boring after six or seven years, and we branched out in many other directions in addition to music. We stayed true to the second one; after 20 years of being in business, we are still tiny.

A few minutes ago, before we began this interview, you mentioned that you started your studio out of your apartment?

Yes. The same as what you had mentioned—the idea was to keep overhead very low so that we would not be financially dependent on our clients and still be able to pick and choose an account based on the merit of the job, rather than how much it paid. I think that turned out to be a very important strategy that influenced the trajectory of the studio greatly.

That is personally interesting to me because Ryan and I are working out of our apartment right now after going out on our own full-time in January. How long did you work out of your apartment before you moved into a studio space?

Forever. We stayed there for 15 years, even though that wasn’t my intent. We’ve only been in our current space about five years now. I had looked for two spaces and, even though looking at real estate in 1993 was much easier than it is now, I didn’t find two good spaces. What I did find was one space on two floors that seemed possible—it was a duplex apartment. I reluctantly put the work and home situation together. Because of that, we introduced some clear rules from the very beginning: we stopped work at 7pm, unless there was a real catastrophe, and we didn’t work on the weekends.

At that point, I had one or two people working with me. Stopping work at 7pm each night brought about a couple of really nice things: mainly, we worked really hard until 7pm, because there was still all of this stuff to do. It created an atmosphere where there wasn’t personal phone calls or things like social media, which didn’t exist back then. We started at 9:30 or 10am and ended at 7pm; in between was hard work. It created a nice separation. At 7pm, it was like, “Whew! We’re done.”

I had seen design studios with a home office where the principals sat around in their bathrobes at 11:30am, looking through the papers. Of course, then they had to work every night until 2am because the work had to get done. I was fearful of that, but it didn’t happen. So many people told me I would love it when work and life were finally separated. I think it’s fine and appropriate, especially now that the age difference between me and some of our team is so big. Plus there are some people who want to come in on the weekend and do this or that, which wouldn’t have been possible before. Yet I didn’t feel relief when we finally moved into a studio. I was fine for the first 15 years.

“My granddad wanted to become a sign painter and designer, but was stopped; my dad would have had a real talent for language, but was stopped. When I expressed a desire to become a graphic designer, I was not stopped.”

It’s been a good transition for us, but we have multiple projects that we’re balancing right now, including a magazine. I think that once that is out, we’ll set more regular hours. But, lately, we’ve been working very long days.

Not that I need to give you advice—

I’ll take it (laughing)

In my case, the strict hours were helpful. When I opened that studio in Hong Kong, I was 29. From ages 26 to 29, I worked 16 hours a day, including weekends. I did not like it. I knew that if I continued that way, I would not continue to be a designer; I’d be burned out by 35 and have to do something else. I liked being a designer too much to go down that route. I thought design was the thing I wanted to do, and it was clear to me when I opened the studio that I had to find a structure that was sustainable for a long time. I also think there’s a time in your life when it’s necessary to work more, but if you want to do this long-term, not everything can be a baby all the time—you can’t keep giving birth. It’s not sustainable for women to do it, and it’s similar with work.

Agreed. So, going back a bit farther, was creativity part of your childhood and were you encouraged in those types of pursuits?

I wasn’t encouraged, but I wasn’t stopped. In Western Austria, that was a big deal. I think that the main reason I wasn’t stopped is because, ultimately, my dad and granddad were stopped. They both took over a store from their predecessors that they were talented enough to be running, but it wasn’t their love. My granddad studied sign making in the late 19th century, which was basically graphic design. You know, graphic design was possibly invented by Toulouse-Lautrec in the beginning of the 20th century in Paris, but before that, that job was done by printers who offered it as part of their service or by sign painters. My granddad was a graphic designer, studied it in an apprenticeship, but was then forced to take over the “antique” store from his dad. He sort of transformed it into a “store for everything” and my dad transformed it into a clothing store. But it was always the proper store in a small town.

My granddad wanted to become a sign painter and designer, but was stopped; my dad would have had a real talent for language, but was stopped. When I expressed a desire to become a graphic designer, I was not stopped.

You weren’t made to take over the family business.

Exactly. Because I had two older brothers who already did. That came in extremely handy. From a family point of view, it would have become crowded in the store with three sons in there. It was perfectly fine.

Are you the youngest?

Yes. I’m the youngest out of six.

Oh, wow. So, did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew that design was what you wanted to do?

I think the first development was simple and easy because I did a lot of work for that magazine. The magazine was culturally active: it organized a concert series here or a demonstration there. All of that needed some sort of graphic design, like a poster. I did those and I liked doing them more than the others at the magazine, so I did a better job. But I don’t think that was an “Aha!” moment; it was more, “I really like doing this.”

Was it more a series of smaller moments that led you into design?

Yeah. I think that the first real moment I had was when studying. Three students and I formed a group and started to do posters for a very well-respected theater in Vienna called Schauspielhaus. We did those posters and it was a blast; we saw them all over the city and the theater was well-respected and had a tradition of quality posters. People went to the theater to buy posters to hang them in their living rooms.

The theater director and I had gotten along very well and he had his eyes on a bigger, abandoned theater in the center of Vienna. The city wanted to tear it down and replace it with apartment buildings. He commissioned a series of posters from me that just needed to mention the name of the theater—because it was a famous name—to bring shame to the city and stop them from being able to tear it down as a fly-by-night act. It was a wonderful job and was very high profile because it launched in one of the most prestigious galleries in Vienna; I was 22 and had a show at the “Gagosian” of Vienna, even though it was only for a day. All the major newspapers and TV stations were there; people wrote about it; it was a big deal. And the theater was saved! It had all the elements—it was like, “Fuck, this shit really works. I can do something and it has an end result.”

That experience also taught me that you can do something and contribute in a minimal way by making something that is delightful. People were pleased, rather than annoyed. Maybe in Vienna more so than in other places, because there are these gigantic kiosks that dot the city, where cultural posters are displayed to share information with people about what’s going on. Some posters are lists, but some are gorgeous imagery that contribute a little to the look of Vienna. If you’re asking for an “Aha!” moment, that would be it. I realized I could do something that’s wonderful and possibly helpful.

Awesome. Have you had any mentors along the way?

The biggest one was Tibor Kalman. While I was studying, I followed the work of M&Co, which was the studio that he ran. As a student, that was the Holy Grail—it made sense to me. The work was smart, witty, conceptual; it took form seriously, but in an understated way, which fit me well at the time. After 50 phone calls, I managed to get an interview with Tibor, and then I worked with him.

Were you here studying at Pratt at that time?

Yes.

And you had your eye on working with Tibor?

In a way. I interviewed him for my thesis and managed to smuggle my portfolio in and show that as well. There was a moment when I showed him something I had done and he rushed to show me a prototype of something they were working on that was quite similar, to prove that they didn’t rip it off from me. Of course, I was flattered to no end that Tibor would be afraid that I would say that. It was wonderful. I sent him the finished thesis, which I had put a lot of work into. Then I heard from somebody else that he kept it in his office, where he only kept 12 books; the rest of the books were outside in the studio. From then on, we kept in contact until after I returned from Hong Kong and worked for him.

What did you learn from working with Tibor?

Oh, there were many, many things. At the very basic level, I learned that it’s important to think about what you do and for whom you do it. The idea of staying small came out of his studio. Before I went to Hong Kong, he knew I was going to be paid well there, and he said, “Don’t you go and spend all the money that they pay you or you’re going to be the whore of ad agencies for the rest of your life.” He had a fantastic way of being able to give advice that others could hear. I witnessed that once when he designed an exhibit for Keith Haring at The Whitney—this was after Keith had already passed. Tibor was there, holding court with a long line of people who wanted to speak to him. I stood close by and listened as Tibor said something important to everybody who stood in that line. And I had the impression that everybody could hear it, that it was actually valuable. It was amazing.

There was a time in New York when almost every good design studio came out of M&Co. It was maybe not quite a dozen, but perhaps around ten. The principals had all worked for M&Co at one time. It was quite an achievement, and I think it also had something to do with people being able to work freely there.

In the meantime, I’ve changed my mind on some things. I don’t think that Tibor was right on everything. I don’t think he ever took beauty or form really seriously, and I think it resulted in a look that is very much of its time, but I wouldn’t want to continue it. I think beauty is more important than Tibor thought, but, nonetheless, he was the most important person in my life. And I’m now friends with his widow, Maira, who is at least as smart, maybe smarter, than Tibor.

When you opened your studio, did you have a mentor in regards to business, or did you figure it out on your own?

Well, at the time, there was a group around called First Tuesdays, which was roughly a dozen design group heads who met on the first Tuesday of the month to talk about something other than design. We talked about anything from health insurance to how to run a business. The subject changed each month. It was always held at somebody’s studio and that person had to provide the drinks and food and was in charge of choosing a subject and preparing something about it. Then everyone in the group would talk about that subject and share how they did things. It was brilliant for somebody like me who knew very little.

From a business perspective, I could also get advice from my brothers in Austria because they both ran businesses. My brother told me that he learned nothing about running a business in business school; he told me it’s basically common sense. You need to take in more money than you’re spending and you need some sort of system that allows you to check that. That’s what I’ve followed. The building of that system—how much money we can spend and how much we need—was a bit of a pain in the ass, but I find the administration of that system relaxing, and I like doing it. After this interview, it’s very likely that I’ll be too tired to sit down and think about a project. It will be much easier to administer the system, whatever that means.

Has there been a point when you’ve decided to take a big risk to moved forward?

Here and there, but not always. There are vast periods where I’m quite lame and tame and risk nothing. I was not born gutsy. I’m the kind of person who needs to talk himself into overcoming his fear. But there are periods when I’m much gutsier and able and willing to overcome fear.

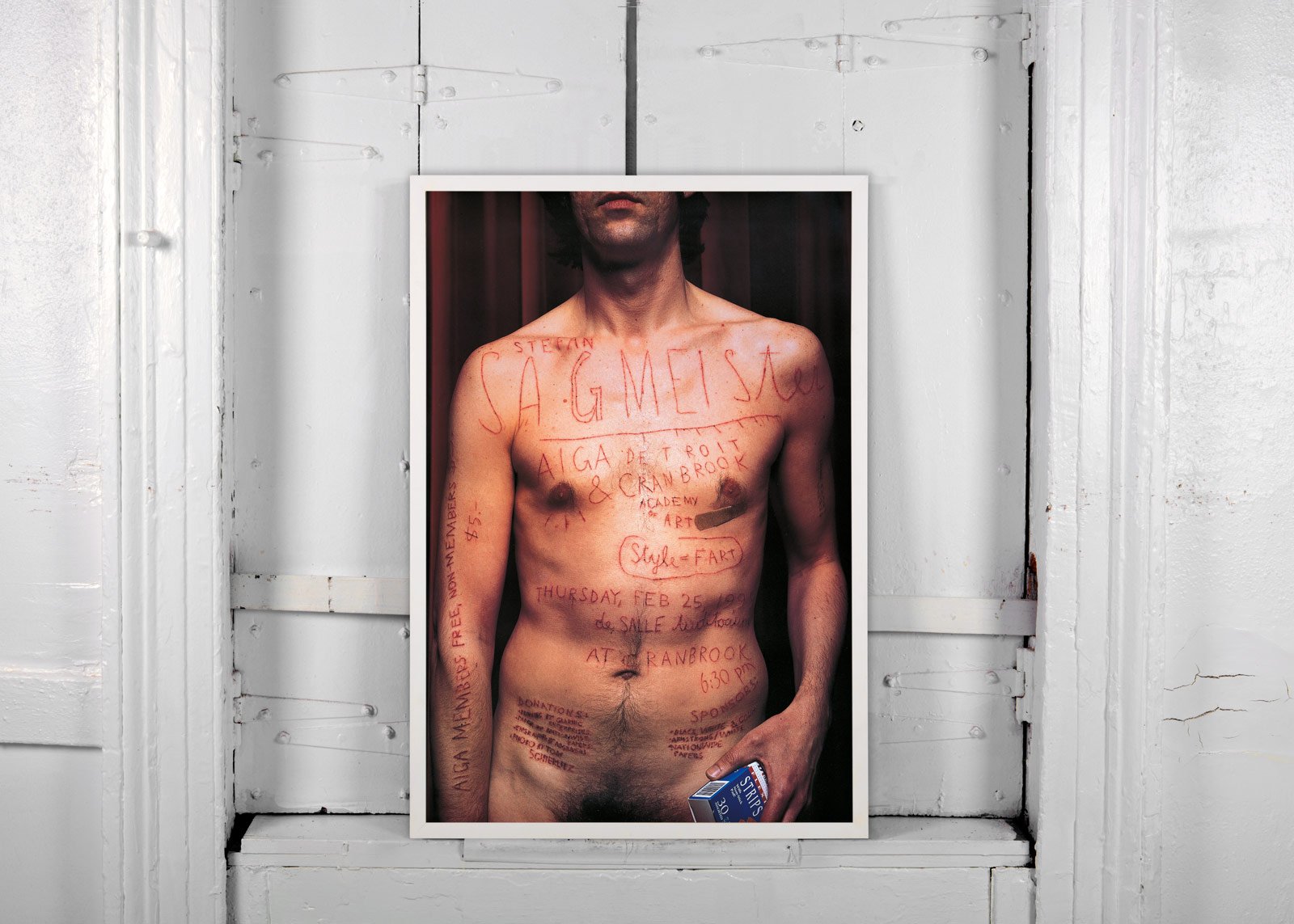

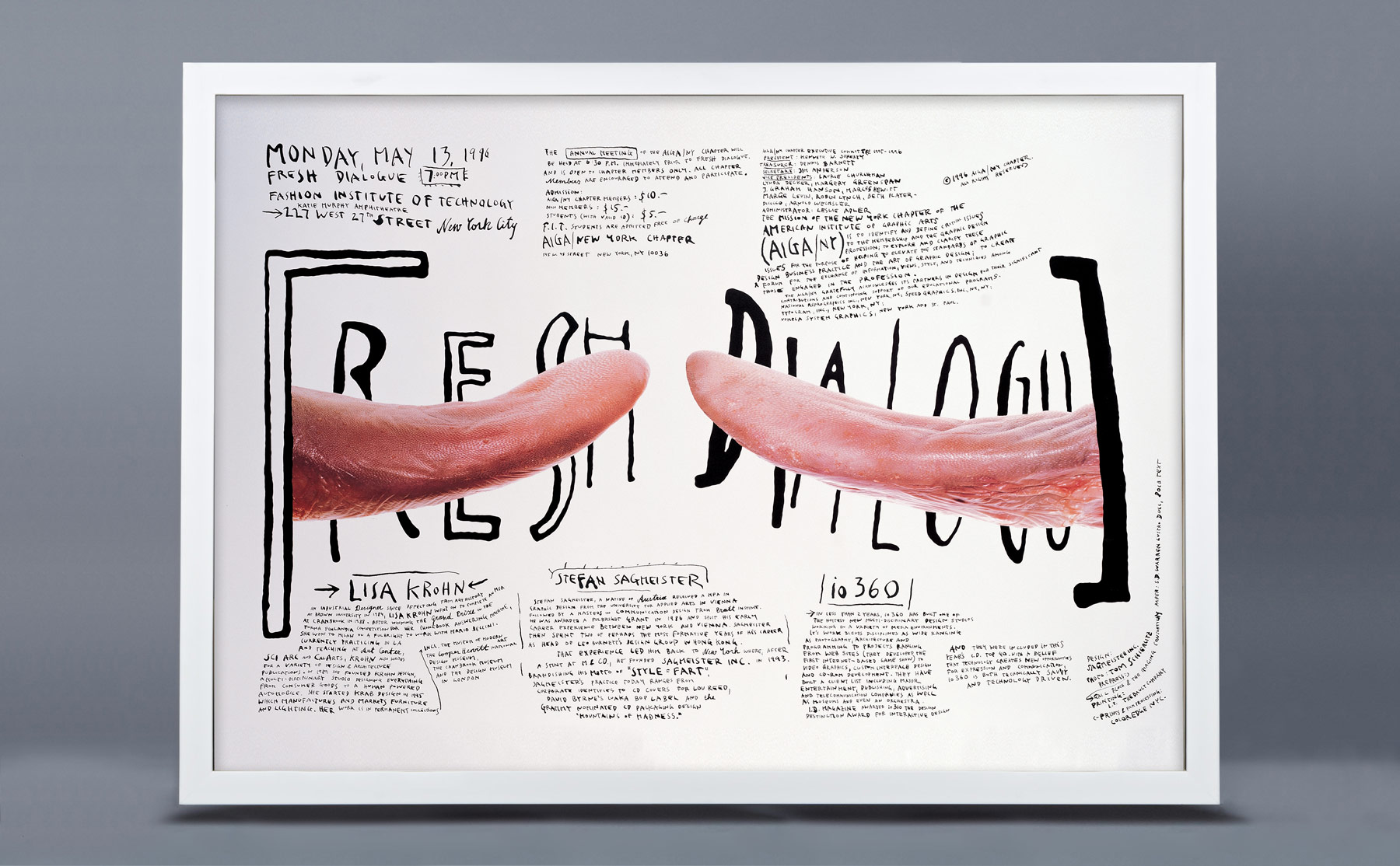

There are two things that come to mind: one was the opening of the studio when we sent out that postcard of me, naked. I was fearful of it at that point, and I had a girlfriend who thought it was going to cost me the only client I had. In some ways, I think that was an important thing to do as a first project because I needed to overcome my fear. It turned out well, meaning the client loved it and put it up in his office with a sticky note attached stating: “The only risk in life is to take no risk.”

When Jessica joined the studio and we sent out the announcement with both of us naked, it wasn’t a risk for me—although it probably was for Jessica. It was kind of jokey and we had done a number of projects with nudity by then. There was zero risk for me.

I think it’s always risky the first time, though. My first sabbatical was similar.

I was going to ask about that.

I had a very uneasy feeling in my stomach: Will we lose all our clients? Will we be forgotten? Will the first seven years we spent building the company be for naught? There were all these real fears. When none of them turned out to be true, the second sabbatical was zero risk.

“I don’t think there is a particular responsibility on designers that is not on other professions…I think there’s a responsibility for all of us to engage on all levels.”

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I don’t think there is a particular responsibility on designers that is not on other professions. I don’t think that designers need to be more responsible than doctors or street sweepers or mayors. I think there’s a responsibility for all of us to engage on all levels. That is partly personal, partly with our friends and family, and partly with society.

We’ve been working for a long time on this happiness project. I’ve learned that there’s a good amount of people who are much smarter than me who think that to engage in something that’s bigger than oneself is a very healthy strategy, simply because it’s satisfying. You see part of that well proven in research; there’s very convincing, authoritative research out there that religious people are happier than non-religious people. Most religious leaders I talk to see at least part of that due to the engagement in something larger than oneself. Religion is a wonderful possibility for that.

I think I’m partly successful in that. Sometimes with design we do work on something that is larger, and sometimes it actually works, but not always.

Are you creatively satisfied?

The lame answer is sometimes. I think that while I’m doing something, I’m never satisfied. But there are times I look at a project and recognize that it’s the best we can do because it’s at the edge of what we’re capable of in that moment. I think that’s about the best you can do. Later on, depending on how they’re received, some projects become a smashing success and I think, “I knew it was fantastic!” (both laughing) And some are utter failures and, of course, I knew that, too!

I think that when it comes to looking back, I’m quite a flag in the wind. My ultimate judgement of a project we’ve done is dependent on how it was received. I don’t think that’s a bad stance to have as a designer. Ultimately, we are in a very audience-related profession, and I think that’s good. If we design a music video for The Rolling Stones and their base audience thinks it’s bad, then it’s a bad video, no matter if I think it’s great or not. By definition, there is a functionality in the things we do. While I’m extremely aware, and even insistent, that a piece of design can never be judged by functionality alone, I think it’s ultimately inhuman to only see things for their functionality. We want things to be more than that. The desire for beauty is something that’s in us, and it’s not trivial.

I’m completely flabbergasted that almost no one talks about beauty within the world of design. If someone does, it’s often, “Well, this is not what we’re about.” Fuck you! If you made something today that was actually beautiful, you did a lot. I think that’s something to be embraced and be proud of. There is this notion out there of designers being seen as people who only make things pretty as if that’s somehow lesser. Just look at the world right now, be it American strip malls or public housing. How much of it is so extremely ugly and built under the guise of functionality, even though it doesn’t work all that well? You can drive for hours and hours through this country, on highways and byways, without encountering beauty. It’s amazing.

“…I think it’s ultimately inhuman to only see things for their functionality. We want things to be more than that. The desire for beauty is something that’s in us, and it’s not trivial.”

Are there any projects you want to explore in the next few years?

Right now, I want to finish The Happy Film. That’s the biggest thing. Having encountered all the difficulties of making the film, simply because of the vastness of the theme, I promised myself that the next project will be about my toenail or something really tiny. (laughing) I don’t know, but, ultimately, I have a couple of directions. Even though I’m not a very secretive person, I try not to talk about future projects, simply because I’ve learned that if I do, I live so much through them that I lose the desire to do them—it’s a very Viennese trait. So many people sit in the cafes in Vienna and talk about the things they want to do and lose the desire to do them.

Also, while making the film, we put together The Happy Show, which was a very satisfying thing to do. It’s been in five cities and will be in two more. That has generated the most amazing feedback of any project I’ve been involved in. To use the language of graphics and the combination of images and words to express something more personal is a largely untapped direction that we got incredible audience feedback from.

We launched The Happy Show in Philadelphia, where the University of Pennsylvania has a very good psychology department. Many credit Martin E.P. Seligman, who is the head of the psychology department there, as the instigator of the entire field of Positive Psychology. Seligman came over to see the show and was a big supporter. It’s much more engaging than a textbook. Since people are physically there, there are many more possibilities for interaction.

What advice would you give to someone who is starting out?

Look around and see if there is an entity that you think does a really good job. If it’s in graphics, is there a graphic design company out there that you love? Work for that company or a similar one for a little while. There are aspects of that that will be applicable and won’t need to be reinvented. But it’s important that you like the direction of the company. In the design world, a design company that does very good work is run totally differently than one that does mediocre work—they have different business practices, different structures and hierarchies, and their makeup will be different.

In my case, I copied everything from M&Co, from doing an estimate to sending the bill, right down to the items that are on the bill. Of course, I asked Tibor and he said it was okay. That gave me confidence when I saw others’ contracts that were 15 pages long and full of legalese; I knew my 2-page contract was okay. If I would have started a studio out of school, I would’ve been using one of those 15-page contracts. Of course, you can only give advice from your own experience; that’s been mine. That worked well for me.

You’ve had a long career, and it’s probably difficult to sum it all up, but is there one thing you’ve learned over the years that has really stuck with you?

Stay small. That was Tibor’s saying because he grew his company too large. When I was at M&Co, there were about 30 people. He always said the most difficult thing about running a design company is not to grow. I opened my studio in ’93 and we’ve basically had 20 good years here in New York; there was a little dip after 9/11 and a dip in ’09, but it would have been possible to grow in almost any direction. Staying small has had many, many advantages for us, and many unexpected ones, too. I thought that staying small would make it easy to keep the quality high and ensure that I remain a designer and not just become a manager; those two things became true, but there are many others. The disadvantage I never expected was that I thought staying small would mean we wouldn’t work internationally, but that’s not true. Only 10–20% of our jobs are in New York; everything else is based outside of the city.

Speaking of the city, how does living in New York influence your work or creativity?

Ultimately, I’m surrounded by a lot of people who do things. That’s inspiring. Maybe it’s not so important now, but it was in the beginning. There are many people here who do big things, and they are not that difficult to get to know. In comparison with other big cities, New York remains a friendly city. In overcoming a little bit of my fear and calling somebody up or walking up to somebody, I don’t think I was ever rejected. After a short amount of time, it’s easy to realize that most people are not that much smarter than you—they just go for it. Why not go for it yourself, too?

In graphic design, that is totally the case. The generation before us, those who are now in their 60s and 70s, were extremely supportive and inviting. That created a real community where competitors genuinely like each other and talk well about each other to clients. It’s beneficial and good for everybody when an industry gets along well like that.

Is it important to you to be part of a community?

Yes. A testament is our fairly strong industry association, AIGA, which is gigantic and, in the world of design organizations, the strongest and best in the world. I can say that with some authority because if a country has a design organization, there’s a strong chance I’ve spoken at one of their events. I don’t think there is one that compares to what we have here. Being part of that community is also a reason I have no desire to leave it. Some of our work goes close to the art world, but I see all of the things we do as design-centric. It’s where we come from, the education we went through, and the core. I’m very happy that design is now defined as something so wide that you can do so many different things and still call yourself a designer. For me, it’s perfect.

I’ve talked with many contemporary artists about the business side of the profession and I think ours is much more fair, normal, reliable. It’s great. I should probably knock on wood somewhere, but in my 20 years of business it’s been very rare that we’ve been cheated or not been paid. I think we’re at job 240 and we had one client that went out of business and owed us a little, and then one client who maliciously refused to pay—that was it out of 240. If you talk about someone who has been in the contemporary art world for 20 years, I think that percentage would go way up.

What is your typical day like?

Right now, I travel a lot. It’s a mixture of exhibitions, talks, and client work. If I’m here in New York, I get up very early. Today I got up at 6:30am, ran on the High Line, went home, and spent half an hour thinking about a job or concept. I was in the studio by 9:30am, did more thinking, put together a couple estimates, did a client meeting during lunch, answered some email. Now I’m taking with you. After this, I’ll do some admin work. Then, at 6pm, I’m meeting with someone from a bank who is thinking of sponsoring The Happy Show in Vienna. Hopefully we’ll be done at 7pm, and then I’ll go see Eddie Izzard at the Beacon Theater.

Do you have any favorite music right now?

In the morning, I listen to Girls in Hawaii at home. In here, Chet Baker was running. There seems to be an approved design music bubble out there. I travel a lot and frequently get picked up by designers at airports. The stuff they play in their cars is remarkably the same: Bon Iver and friends. There are some exceptions to that, though.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

My all-time favorite TV show is The Sopranos, partly because of the historical significance. It seemed to have created this entire genre of the long-term narrative that’s told with a sort of realism that appeals to me. It built on its successes and became better as it went on. The Wire is the other one.

For films, I really like Spike Jonze. Adaptation is way up there. It’s smart and entertaining; it’s fun to watch, but there’s a depth to it. Last year, my favorite film to watch was Her, but my real favorites were two docs that were nominated for Oscars, but I loved them as a combination: The Act of Killing and 20 Feet from Stardom. They’re extremely different from each other, but, in some way, I think they work well as a double feature. They both are of a particular subject, one being genocide in Indonesia and the other about a backup singer, but they both address the human condition. One about its dark aspect and one about its light aspect.

Do you have a favorite book?

A Man in Love by the Norwegian author, Karl Ove Knausgaard. It is extremely honest and hyper-realistic.

What is your favorite food?

Tiny Bow—soup dumplings at Joe’s Shanghai in Chinatown.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

Hmm. I would have to think about it. It’s one of those things that Tibor was interested in at one of the various points I met up with him, and I didn’t get it at the time. Toward the end of his life, when he was already sick, Tibor was really interested in his legacy. I thought, “Really? That’s so boring.” But I’m sure that there’s going to be a time in my life when I’m interested in my legacy and probably, hopefully, actively worrying about it and building it, but not now.

I know that there is a negative connotation to thinking about your legacy, like you’re building a monument to yourself. I don’t see anything wrong with it at all. There was a modernist artist named Sol LeWitt, who did a lot of work that was instructional; he sold those instructions to museums. The instructions might say: “There needs to be a wall. The wall needs to be divided into three stripes, starting red and going to blue.”

At MASS MoCa, there is a whole building dedicated to Sol LeWitt; it’s a giant factory building with three floors of his work, and it will exist for 35 years. That’s where legacy comes in—he underwrote the exhibition; I think he paid for this thing. He talked to MASS MoCa, who was going to give him one floor, but he thought, why not have the whole building? He gave them an endowment to pay for the building for 35 years, figuring that his work would last through two generations of people who would go see it. The reason I became a Sol LeWitt fan was because I saw this giant building of work, properly displayed in one space. He clearly thought about his legacy, and I actually like that he actively worked on building it.