- Interview by Ryan & Tina Essmaker April 1, 2014

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Austin Kleon

- designer

- writer

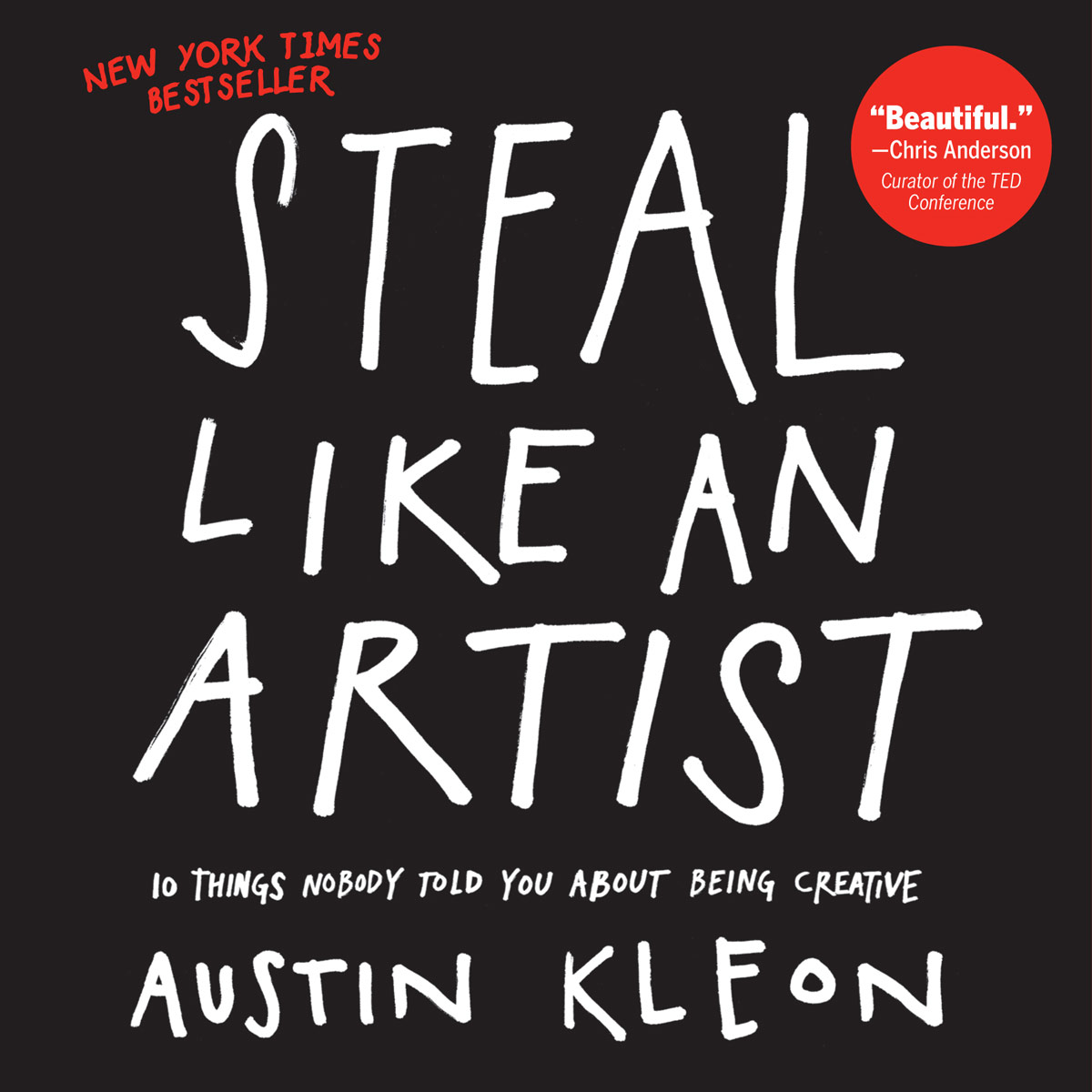

Austin Kleon is the New York Times bestselling author of three illustrated books: Steal Like an Artist, Show Your Work!, and Newspaper Blackout. His work has been translated into over a dozen languages and featured on NPR’s Morning Edition, PBS NewsHour, and in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. He speaks about creativity in the digital age for organizations such as Pixar, Google, SXSW, and TEDx. He grew up in Ohio, but now lives in Austin, Texas, with his wife, Meghan, and son, Owen.

Interview

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I was raised in a small, rural town in Ohio called Circleville, probably not too far from where Chris Glass grew up. I lived in the middle of cornfields, and I think that’s where a lot of my inspiration came from. Thanks to my dad, I have two half-brothers and a stepsister, but I am my mother’s only child, which I believe is biographically significant. (laughing) Both my parents worked in education: my dad was an associate professor for Ohio State and ran the 4-H program in our county, and my mother worked in education as a guidance counselor and later as an elementary and high school principal. My mom set aside dedicated playtimes for me; she’d give me Play-Doh and ask, “Will you make me something?” I also remember copying Garfield cartoons with my cousin using butcher paper and crayons on my grandmother’s kitchen floor.

In elementary school, I became interested in seeing pictures and words together, like in comics. I remember one class project where we each made a little book by writing a 10-page story and drawing pictures for it. But then what happened is what happens to a lot of people in our current education system. Everything is connected when you are younger, but it gets separated into subjects as you get older. It’s no longer copying Garfield cartoons and making illustrated books—all of a sudden, it is divided into art class and English class.

After that point, words and pictures began to split apart for me. I felt pulled between visual art and writing, and they continued to battle each other throughout high school and college. In the middle of all of that, I was also an amateur musician. I spent most of my teenage years playing in bands and making fake album covers.

Tina: What did you play?

I played a lot of instruments, but I was mainly trained in classical piano. Of course, when I heard Green Day, I wanted a guitar. My best friend is a world-class drummer, and I grew up playing in bands with him.

I was a nerd in high school and graduated as valedictorian of my class. My mom pushed me super hard to get good grades so I could get into college, because that was a way out for me; that was how I could get where I wanted to go. I was lucky enough to find Miami University, a beautiful little campus in Ohio, that had a funky, interdisciplinary studies program called the Western College Program. The whole premise of it was for students to make up their own major and take courses from different disciplines. I took art classes, studied classics and Greek and Roman literature, and wrote in creative writing workshops. Despite being in that program, though, I still felt pressured to pick between writing and art.

Tina: Were you trying to figure out a way to combine the two?

Yes, but I hadn’t figured out how to do that.

Eventually, I decided that literature was the more serious and responsible subject to study. For six months, I went to Cambridge University on an exchange program. I studied 16th-century tragedies and the novels of Dostoyevsky and Dickens. I was basically living in Raskolnikov’s closet while I was there—the student housing conditions in the UK are pretty dismal. (laughing) I was losing my mind writing terrible papers for my tutor. One day, I had a one-on-one tutorial to go over Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend with my professor. I was trying to explain what the book was like, so I took out a piece of notebook paper and drew a map of London; as I drew, I said, “Here is what happens when the characters are in these parts of London, and this is how the narrative maps.” It was a really crude map, but my professor looked at it and said, “This is better than anything you’ve turned in for me.” That crummy map was better than any of the writing I had done! I knew that I had to bring drawing back into my life, so I bought a sketchbook and started drawing again.

After the exchange program, I came back to the States and got acquainted with a professor named Sean Duncan, who showed me serious graphic novels from artists like Chris Ware and Art Spiegelman. I still wasn’t ready to do comics in particular, so I did my senior thesis on how to use visual thinking techniques to write literary fiction, how to draw maps for settings, and how to storyboard a narrative before writing it.

Once I graduated, I didn’t really have any career prospects. I met my wife while I was in college, and I knew I wanted to be with her, so we moved to her hometown of Cleveland. I was lucky to get a job at a public library where I worked for two years. It was amazing because I only worked 20 hours a week, but received full benefits and had unlimited access to books. Essentially, working part-time at the library was my grad school.

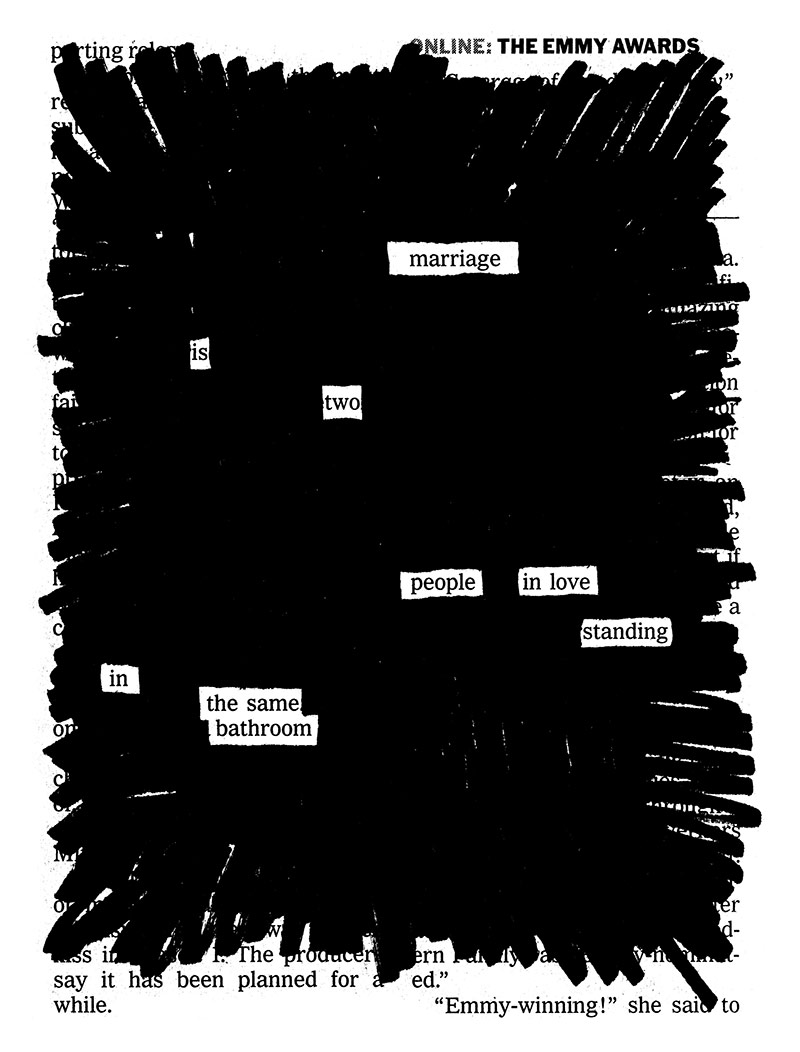

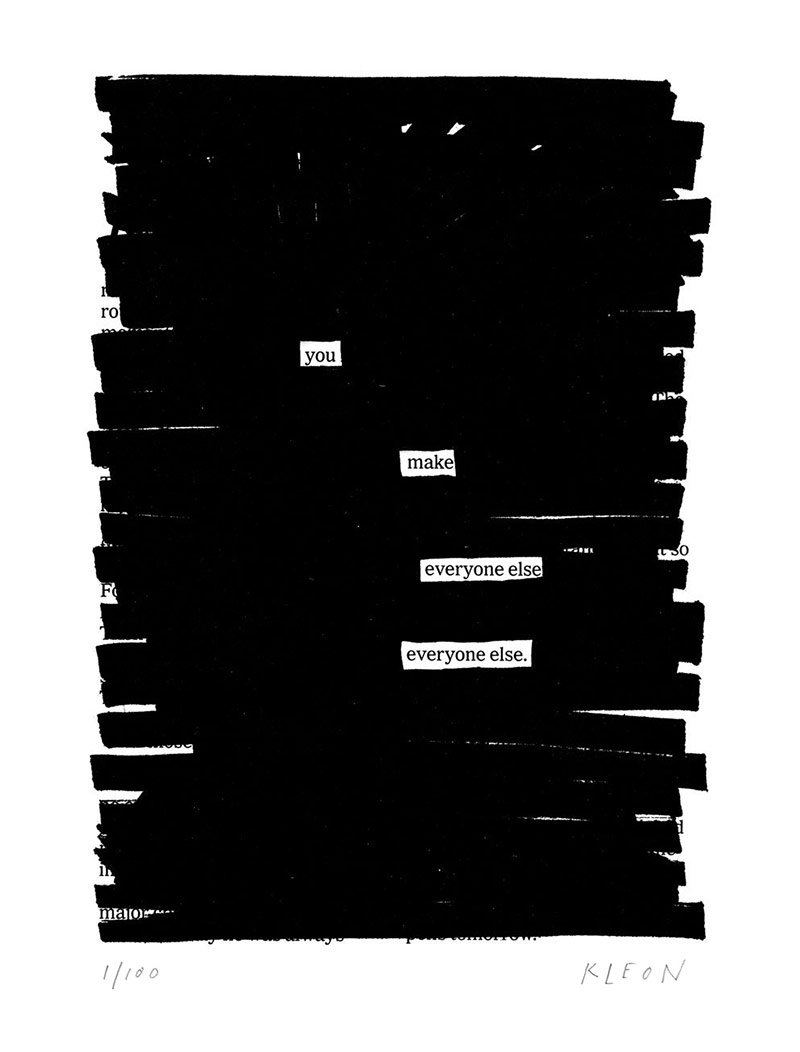

While I worked there, a few things happened that led to me becoming a web designer. First, I was still trying to be a writer at the time, so I started a blog and began making my newspaper blackout poems as a kind of writing exercise to post online. Around that same time, I came across the work of statistician and information designer Edward Tufte, along with a whole scene of cartoonists in St. Louis who worked for an information design company called XPLANE. I became really interested in the work of a few of those guys, particularly Kevin Huizenga and Dan Zettwoch. I was too dumb to know what a designer was; when I found their work, I thought, “Hey, putting pictures and words together to give people information is kind of like comics.” In addition to those discoveries, one of my jobs at the library was teaching senior citizens how to use computers, and that’s how I realized that people designed websites for a living; I wanted to learn how to do that, too. When my wife got into grad school in Austin, Texas, I decided to try to get a job as a web designer.

Tina: Had you done any paying design jobs yet?

No, but I felt like I knew enough to muddle through it. I had been monkeying with my own site and teaching myself HTML and CSS, so I applied for a position in the law school at the University of Texas. I told them, “I have a blog, I’ve learned HTML, I have a library background, and I’d really like to get into web design.” The people there were cool enough to hire me, and the work in the beginning was mainly putting additional information into pre-existing HTML forms and making sure the markup was semantic. Then I moved on to building my own sites. I spent over three years with the law school, and the webmaster there, Adam Norwood, taught me everything I know about the web.

In addition to work, I had continued writing on my blog, and that’s when my blackout poems started to take off. When I was just some weirdo from Cleveland making them, people didn’t care, but when I moved to Texas, people started paying attention. At one point, NPR did a story on it, in which they called me a “Texas poet.” I wasn’t from Texas and I didn’t consider myself a poet, but the work was spread around and an editor from HarperCollins called to ask, “Have you thought about turning this into a book?” I told her, “Hell yeah, I’ve thought about turning it into a book.” As everyone who has ever done a poetry book knows, it wasn’t enough to allow me to quit my day job. It took two years for Newspaper Blackout to come out, and I worked on it while I was still doing web design for the law school. It was a brutal process, but it became a poetry bestseller, which is very relative. (laughing)

Once that happened, I suddenly realized that I wasn’t really a designer; I was a writer with a design sensibility. I had a few friends who were copywriters, and they said, “Have you considered copywriting?” I hadn’t really thought about it, but some of the cartoonists I knew had been copywriters. I applied to be a copywriter at a digital ad agency called Springbox. I pitched myself by saying that I wanted to learn more about marketing; I said, “I don’t have ad experience, but I’ve got a web background, I’m a writer, and I’ve put out a book.” I had a buddy who put in a good word, and they were cool enough to hire me. I worked for them as a copywriter for a little over a year. During that time, I told myself that I wasn’t going to write another book. I was going to be a copywriter and make my way up in the ad world. I’d do my weird writing and artwork on the side.

After Newspaper Blackout came out, I started getting speaking gigs. Broome Community College in Upstate New York asked me to come speak, but there was a misunderstanding on my part: I thought it was for a commencement ceremony because it was at the end of the school year, but it wasn’t. I imagined what I would say to a group of young adults about what they should do with their lives. I had been collecting quotes about influence, how nothing we create is original, and how everything builds on what came before it. I collected those into two blog posts, “25 Quotes to Help You Steal Like an Artist” and “25 More Quotes to Help You Steal Like an Artist.” I had to give the college a name for my speech, so I told them, “How to Steal Like an Artist,” thinking that was a good title to start from. Then I had to write the talk, and I thought, “Oh, shit, what am I going to say?” I went for a walk with my wife and she said the best speech she had ever heard was a woman who just listed 10 things she wished she’d known as a student. I thought that was a great idea and decided to steal it. (laughing) I went back through my blog and came up with a list of 10 things that I wished I had known when I was starting out.

Then I flew up to Binghamton, New York, to give my speech. What I love about community colleges and smaller universities that are off the beaten path is that the students are hungry. It’s not like Harvard where the students have a Nobel Laureate coming in to speak. For these kids, seeing someone who had actually written a book was pretty cool. My talk went over really well; tellingly, it went over better with the parents than with the students. Since I’m a millennial, and I don’t believe something actually happened unless it’s online, I decided to take the slides and text from my speech and put it on my blog. When I did that, it blew up almost overnight.

Tina: And that was the basis for your book, Steal Like an Artist?

Yeah. Back when Newspaper Blackout first came out, I wrote a terrible letter to my now-agent that said, “Hey, I need an agent now!” He responded with: “You’d better hope that book fucking sells a million copies and get back to me when it does.” Obviously, it didn’t. (laughing) What happened next was a funny reminder of our connected world. I was already being contacted by editors about turning the “Steal Like an Artist” blog post into a book. I followed my agent online and saw that he tweeted about how great the post was, so I emailed him to ask is he was interested in turning it into a book with me. He said, “Yeah, let’s do it.”

Steal Like an Artist made a decent amount of money, but it wasn’t necessarily going to change my life; I planned to keep my day job. The weird thing was that right when the book came out, Springbox went up for sale, and people were jumping ship left and right. I asked my boss if I could have two months off to go on a book tour, but that wasn’t going to happen. Since the company was up for sale, I didn’t know if I was going to have a job in another month anyway, so I jumped ship, too. Then Steal Like an Artist landed on the bestseller lists and started doing really well. That’s when I realized that this could be my career.

“In all creative work, there is a balance between what you want to give the world and what the world needs: if you’re lucky, your work is in the middle.”

Tina: What happened next?

After that, it became clear that I might be able to make a living with three income streams: art sales, book sales and advances, and speaking gigs. So that’s what I did.

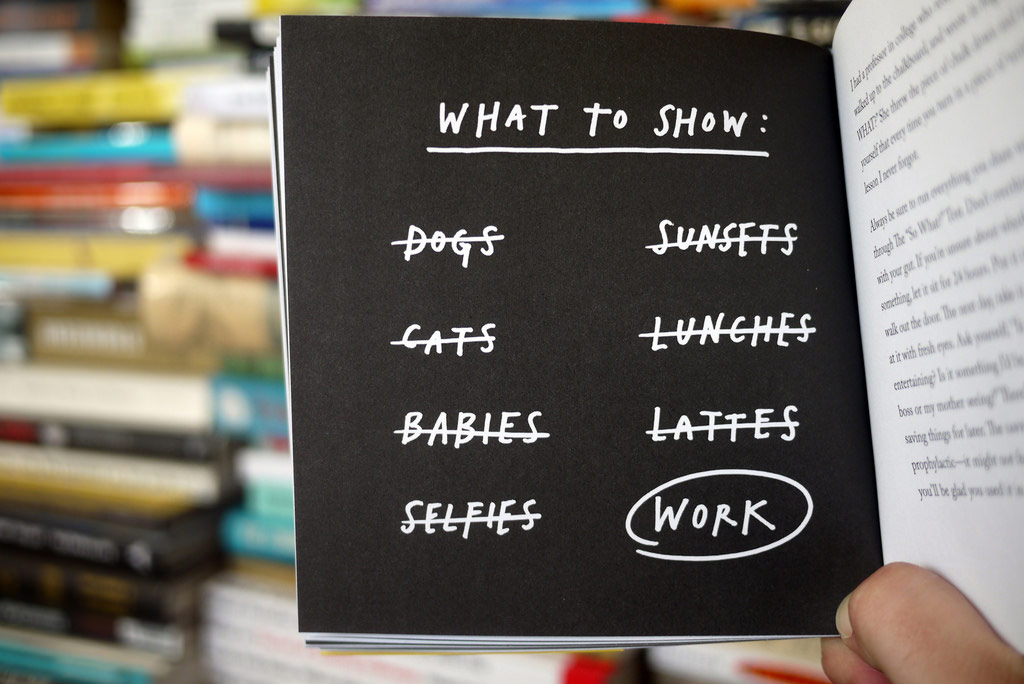

As soon as Steal Like an Artist came out, it was as if people were asking, “OK, kid, what else do you have?” As soon as people smell success, they start asking questions like, “How did you do that?” and, “How do I do that?” People constantly asked me about self-promotion and since almost every creative person I know dislikes self-promotion, I decided to write a book that offered an alternative to that. I wanted to write about how it can be done in a way that contributes to our culture instead of just pimping out one’s work. That’s where my latest book, Show Your Work, came from.

Tina: It’s cool how everything came out of personal experiences. That resonates with people more than asking, “What can I come up with to make money?”

Yeah. Nothing was ever planned. It’s interesting looking back. All three of my day jobs have come from a side project. I got lucky with my gig at the library—I was a book nerd with a decent transcript—but the web design job was purely because of my blog and what I had done online; and I got hired as a copywriter because of the book I had written in the evenings on top of my day job.

This latest book was the result of me worrying that my previous two books were flukes. Newspaper Blackout and Steal Like an Artist included work I put out that later presented itself in book form. The challenge with Show Your Work was actually coming up with an idea for a book first and then executing it, publishing it, and seeing if it would succeed.

The newest challenge I’m facing is continuing to make things and not just talk about making them. I’m in a very dangerous position right now; I could shave my head, put on a robe, and become the guru. I could be the guy who flies around, talking about being creative, gets a nice paycheck, and goes home. That’s not interesting to me. If there’s a reason people like my books, it’s because they came out of my practice and what I learned while I was working. Now that Show Your Work is out and doing okay, the next big task is making sure that I stay connected to my work. How do I ensure that I don’t lose my desire for wanting to make stuff?

Ryan: Just keep making stuff.

That’s the thing! What’s great about a day job where I talk about making stuff is that it allows me the freedom to actually make stuff now. They fuel one another.

Tina: Have you had any mentors along the way?

Yes. When I was 13, something amazing happened. My art teacher, Robin Helsel, who I had in elementary and middle school, asked us to write to an artist. I chose Winston Smith, an artist from the San Francisco punk scene. He made amazing, surreal collages; the one people are probably most familiar with is the cover of Green Day’s Insomniac album. He also designed the Dead Kennedys’ logo. Anyway, I opened Microsoft Works on my computer and used the Ransom Note font to write him a letter. A few months went by and no one in my class received a response.

Then, one day I received a huge manila envelope in the mail. Inside was a 14-page long, hand-drawn letter from Winston Smith! He answered all of my questions, talked about his experiences as an artist, and filled the rest of the envelope with clippings of his work. The letter was incredible because it had all of the views you would normally hear from a subversive punk-rock artist, like, “Question authority,” and, “Don’t trust the Man!” But it was also full of really practical advice like, “Get good grades in school,” and, “Don’t do a lot of drugs,” and, “Take care of yourself, because you’re going to need your body later.” That letter had a huge impact on my life because it made me realize that I didn’t have to turn into a dirtbag to be an artist. A lot of those lessons in Winston’s original letter made their way into Steal Like an Artist.

He was one mentor. Another was a really great college professor at Miami University named Steven Bauer. He was nicer to me than I probably deserved, (laughing) and he helped me discover that I’m not a serious writer. I was writing depressing stories about small-town life, trying to be a tortured artist like Hemingway or Raymond Carver. On a lark, I wrote one funny story, and Steven said, “This is better than all of your other work.” He told me that I needed to explore my comic voice.

When I moved to Cleveland, there were a few writers who I admired there. I went to fiction readings, drew the writers, then wrote blog posts about them. Through that, I met a lot of them, including Dan Chaon. Dan runs the creative writing program at Oberlin College and often took me out for coffee or invited me to events when someone like George Saunders was in town.

One day in 2006, Dan asked if I knew who Lynda Barry was. When I said I didn’t, he told me to attend a talk she was giving at Oberlin. Going to that lecture changed my life: I had been trying to combine pictures and words, and Lynda Barry is a cartoonist and a writer. Dan invited me out to a bar with Lynda afterwards, and we talked for two hours. It was great being around her and her amazing energy that night. I feel like I’ve been running my career off of those fumes ever since.

Tina: What a great experience it must have been to meet someone with so many connections who was able to bring you into the fold.

Yeah! And ever since then, Lynda has been a mentor from afar. After that, I saw a Saul Steinberg show in New York, and everything became clear to me: I realized how I could combine pictures with words. If my work is a venn diagram, then the intersecting circles are pictures, words, and the web.

Has there been a point when you’ve taken a big risk to move forward?

I’m not a big risk-taker. For one thing, my wife and I have been together for 10 years and married for 7, so I’ve always had a family to think about and support.

When I was growing up, I didn’t know any professional artists, so I didn’t know that people could do this for a living. Then, when I was a junior in college, I went on my first trip to New York. Miami University had a program where a limited number of students could submit an essay for the chance to visit New York for a week during spring break. The chosen students were flown to New York to meet alumni who were working in the arts. I was one of the chosen students.

The patron put up the money for the program was named Ted Rogers, and he lived in Jerry Seinfeld’s building on the Upper West Side. We had tea at his place, and I told him that I was interested in classic literature. He said, “Oh! Well, come upstairs.” He showed me a beautiful library lined with books. Meeting him and others who had attended my college and were now making a living in New York blew my mind. I thought, “Maybe I can do this,” and it gave me a little bit of courage.

Tina: Did that feel like an “aha” moment, like maybe that life was attainable?

Yeah. I thought, “It’s probably not going to happen, but it could.” In my senior year of college, my professor Steven Bauer taught a wonderful class called The Publishing Marketplace. It was like a Scared Straight program for writing students—if that course was taught to freshmen, nobody would major in creative writing. Steven was clear with us; he said, “It’s going to be incredibly difficult to make a living as a writer, so you’re probably going to have to do something else on the side.” I thought I would have a day job forever and do creative work on the side.

If I’ve taken risks in my life, they have been extremely calculated; I try to save the real risk for the work. My favorite quote is by Gustave Flaubert, who said, “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” That’s my favorite quote about creativity, and that is always how I’ve tried to live.

Ryan: I like that. Are you creatively satisfied?

No, I’m not. I’m very satisfied with my life: I love my family, being a dad, being married; I love my house and my city. Honestly, I have more right now than I ever dreamed of. I’ve put books out into the world that people read, I get to write for a living, and I get to read for a living! That’s cool. I always joke with people that the reason I’m a writer is so I can be a professional reader. (laughing) It’s a good life.

But as far as work goes, all I think about is how I can do better. What really interests me is what’s next. I really like doing the work. I’m trying to create a daily practice, no matter what, without letting success get in the way. I want to make stuff and not worry so much about the results.

There’s a book by Ian Svenonius called Supernatural Strategies for Making a Rock ‘n’ Roll Group. The author grew up in the DC hardcore scene, and it’s a wild read. There’s a part in the book where Ian says, “If you’re a doctor or a lawyer or a nurse or a teacher, people are cool with that. If you’re an artist or a filmmaker or a photographer, the question you always get asked, no matter what, is, ‘What’s next?’” That question will always linger if you’re in a creative industry. If you’re a surgeon, nobody ever asks, “What’s next?” They know what’s next! Someone’s going to fuck up their arm and they’re going to need surgery. If you’re lawyer, someone’s going to get divorced; if you’re a doctor, somebody is going to get sick. I’ve decided that I need to be comfortable with not knowing what comes next. I have to go back to that practice and let the next thing come.

“…as far as work goes, all I think about is how I can do better. What really interests me is what’s next. I really like doing the work. I’m trying to create a daily practice, no matter what, without letting success get in the way. I want to make stuff and not worry so much about the results.”

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I do. One of the reasons I wrote Show Your Work is because something I tried to emphasize in Steal Like an Artist is that we’re brought to creative work by other artists. We fall in love with art because we’re given a box of crayons or we see a movie that changes our lives and then we want to be filmmakers. The whole concept of Steal Like an Artist is to honor our influencers by taking what they have done and turning it into something else that we can then add to. If we think of culture as a big gumbo, then we take a little gumbo and add something to the mix. It goes further than just stealing. Creativity is not the lone genius myth—it is actually the result of connectedness.

I became interested in Brian Eno’s idea of “scenius” versus genius wherein scenius is a communal form of genius. Many great ideas in history weren’t the result of one person; they were the result of a whole scene of people. That was a mind-blowing concept to me, and I wanted to write a book about it by taking the ickiness of self-promotion and reframing it as sharing. Switching your notion of creativity from the genius model to the scenius model means that instead of thinking, “What do I have to give to the world?” you ask, “What does the world need from me?” Sometimes that’s an easier way to get started. Usually, when we talk about creativity, it’s about self-expression, which is great, but for work to be art or design, there has to be someone on the other end. The audience makes the work come alive. Margaret Atwood said something along the lines of, “A book is sheet music that a reader sits down to play.”

Tina: I think we create because we hope that it will connect us to someone else.

Right: connection creates meaning. It’s about balancing the desire to do something for the love of it, and sharing it in a way that contributes to the world.

What advice would you give to a young person starting out?

Sublimate your ego as much as you can. When you’re in college, you have a captive audience. Your professor is getting paid to read your writing and your fellow classmates are paying to read your writing. Once you graduate, you will be faced with the hard reality that nobody gives a shit. Steven Pressfield said, “It’s not that people are mean or cruel, they’re just busy.” You have to understand that it’s not about your ego; it’s about what you can do for the culture at large.

In all creative work, there is a balance between what you want to give the world and what the world needs: if you’re lucky, your work is in the middle. Because of that, I believe that every job has a service element to it. If you want to make creativity your job, you have to think about what your creativity is in service of. Think less about how you can be a genius and more about the scenius. What can you contribute?

The other benefit to that way of thinking is that it frees people up. My agent is actually a reformed writer: he realized that he really didn’t want to write, but he still wanted to be a part of the literary community. Now he helps writers get their work out to the world, which is just as important as writing. The minute you start thinking about what you can honestly offer to the community you want to be a part of is when you start to discover how to integrate your talent into that community.

That is so different from how most of us think about art, though. We tend to think about art as therapy or self-expression, but at a certain point, if you’re going to make a go of it, your work has to become something else.

Tina: What does a typical day look like for you?

I try to treat my work like a day job by keeping regular hours. The first part of my morning is the raw, creative part; I get up, walk out to the studio, meditate, and write my blog posts or poems. In the afternoons, I do admin: answering emails, doing interviews, Photoshopping, updating my website—all that crap. Then at 5pm, I knock off to go hang out with my family. I try to keep regular hours. Otherwise, what’s the point? I didn’t get into this to work 90 hours a week.

Tina: I don’t think anyone wants to work 90 hours a week, no matter what they’re doing.

Nothing is fun if you do it that much. It becomes too much of a good thing.

Ryan: Even if you’re doing what you love, it’s still work.

Absolutely. I have a couple problems with the “do what you love” ideology. The first issue I have is that it is impossible for everyone to do what they love. As a society, we cannot function without people doing the dirty work: someone has to take out the garbage; someone has to make sure the plumbing is running; someone has to make sure the electric is on for all the startups. (laughing) The fact is that a lot of people aren’t going to be able to make money doing what they love, so it starts to make people feel bad. That pressure can make someone with a good, stable, bread-winning job feel like he or she has to toss it out because it’s not what they genuinely want to be doing.

The second issue I have with doing what you love—and I’m sure you two are finding this out—is the pressure to overwork. People are led to believe that if they’re doing what they love, then they should be working long hours, or even all day.

Tina: Yes, especially when you work for yourself. You’re not thinking, “Well, it’s 5pm. I’m done now.” There is still work that needs to be done.

Right. My job is awesome: I feel like I’m doing what I was meant to do. However, there is a shit-ton of admin that comes with it that is not fun, and that’s the work part.

How does living in Austin, Texas, impact the work you do, and is it important for you to be a part of the creative community there?

This comes up a lot because people are fascinated by Austin. It’s tricky. This goes along with another piece of advice I would give: get outside of your discipline. There are some really good writers and artists in Austin, but I don’t hang out with them. The people I hang out with are designers, filmmakers, musicians, or people in tech. Hanging out with people from different art forms cross-pollinates creativity for me in a positive way.

I’ve started to like Austin much more since becoming a parent because it’s a kid-friendly place. Yet there are still things I don’t like: the heat, the traffic, and how crowded it’s becoming. It’s been a very livable place; it didn’t used to take a lot of dough to live here, but that is changing and the city is becoming less and less affordable.

Austin also comes with a phenomenon called the “velvet rut.” Back in the 70s, a lot of musicians moved to Austin because it was so laid-back and cheap, and because it was a respite from Nashville. These musicians didn’t need a lot to live on, and they were comfortable with gigging, so they never really became ambitious to do anything else because Austin was so comfortable: that’s the velvet rut. It’s real, and it’s easy to get stuck in it. You start to think, “I’ve got my breakfast tacos, my sunshine, my BBQ, and my food trucks. I’m just going to sit here and do my thing.”

Tina: Do you think traveling helps to keep you out of that rut?

I think so, but my community has always been online. Instead of having a geographical scene, I’ve had blog and Twitter buddies. It has been really fun to meet those people in the world. So many of my friendships started online, and then crossed over into being real-world friendships.

What music are you listening to right now?

Oh, I think St. Vincent’s new self-titled album is incredible. The way she has come into her own is so inspirational. She keeps stepping up her fucking game! That question I mentioned earlier: “What’s next?” She has answered that every time. I really enjoyed the Future Islands’ performance on The Late Show; I’ve watched that about 20 times now. I loved their last album, On The Water, and have been listening to that recently. I’ve also been into Curtis Mayfield lately. I love old soul music.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

I don’t watch movies anymore because I have a kid, but I do enjoy TV shows. I really like True Detective, I loved the first couple of seasons of Bob’s Burgers, and I think The Americans is great, but Justified is my favorite show on TV. I enjoy staples like Louie, and I like Girls, too. I actually hated Girls when I first started watching it, but now I feel like there is something charming about it that I don’t understand. I’ve heard Cosmos is really good, too, so I’d like to watch that at some point.

What are your favorite books?

The book I’m still buzzing about is called The Sisters Brothers by Patrick deWitt—that was my favorite book last year. I loved Mason Currey’s book, Daily Rituals: How Artists Work, and I think that all artists or creative types should read it.

As far as the classics go, Lewis Hyde’s books are great. I like people from the Midwest who use pictures and words, so I love Charles Schulz, Kurt Vonnegut, and Lynda Barry. I’ll throw in Saul Steinberg, too, because he’s Romanian and so am I. (laughing)

Do you have any favorite foods?

My relationship to food is really strange right now. People always ask me about barbecue because I live in Texas, but I’ve been eating vegan lately. Honestly, though, if I could eat anything at any moment, I would eat my mom’s fried chicken and mashed potatoes with gravy. My grandma used to cook it for 20 people every Sunday! That’s why everybody in my family has an ass on them. (laughing)

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I hope that no one needs me. I believe that if you do your work right, then the world shouldn’t need you anymore. A good legacy would be falling off of the planet and having someone else pick up my torch. To be perfectly honest, though, I hope my son grows up to be a good man. Once you have children, they literally become your legacy, and that’s what you leave behind.

“Sublimate your ego as much as you can. When you’re in college, you have a captive audience…Once you graduate, you will be faced with the hard reality that nobody gives a shit…You have to understand that it’s not about your ego; it’s about what you can do for the culture at large.”