Emergence Issue: TGD's fifth issue features a dynamic group of 15 creators who are deeply committed to addressing systematic challenges in their communities through creativity and emerging ideologies. Buy Now

How do you explain your work?

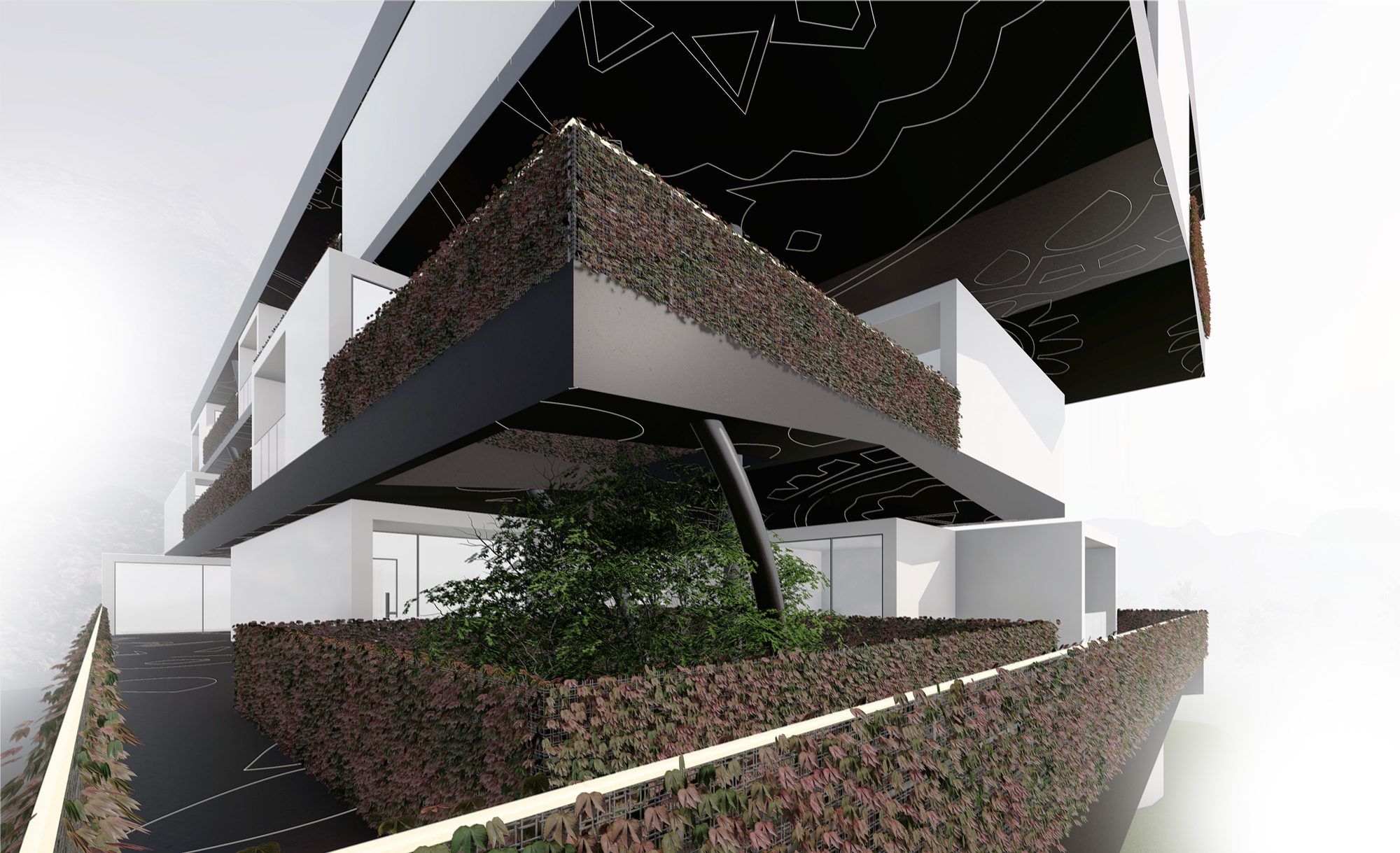

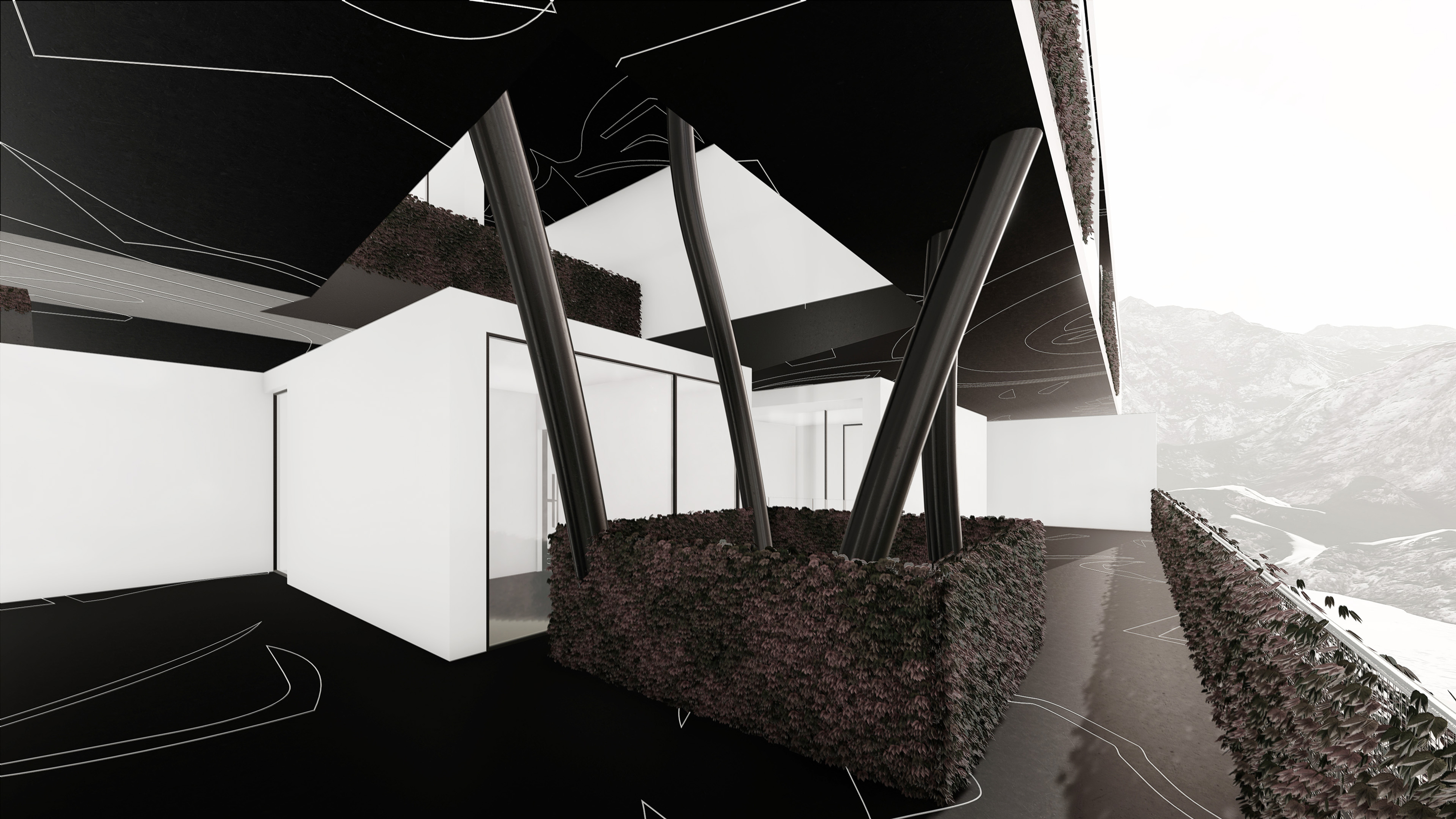

I am specifically interested in improving the built environment in Black neighborhoods. Creating buildings that look and feel Black—community oriented and community-driven projects.

I understand you were born in Moreno Valley. Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up and what that was like?

Moreno Valley is almost an hour outside LA, in the Inland Empire, where a lot of the Black population from LA ended up being displaced. A lot of people I grew up with are from LA. I think it definitely had an impact on how I handle things creatively or businesswise.

Were you from a creative family?

No, I’m not from a creative family at all. [Laughs] Growing up, I was more into sports. I was into hustling more than creativity early on. I started selling T-shirts, making T-shirts, doing a little design. It’s a unique lens to come to a creative career through the hustle and entrepreneurial side of creativity.

Talk to me a little bit about the shirts and teenage Demar’s vision. Somebody at middle school was selling Milky Ways, right?

They had a big cart, and I’m seeing them sell and make money. Milky Way is trash, but we didn’t have any other candy available until lunchtime. So he gives me half, and he’s like: “All right, go sell them. I’m gonna give you half the money.” At the end of the day, I have like $12. At 11, that’s cool, you know.

Yeah.

But then he took $6 back. I’m like: “Oh, my God. He took all the money. This don’t even make no sense.” [Laughs] So the next day, I went and got the variety pack, and I started selling them for a quarter cheaper than the dude was selling his. That’s the earliest point of like: “Oh, okay. I can make some money.” That led into the shirts. Once I got into high school and was too cool to sell candy, I was like, “How you gonna make money?” I’m 14, 15. I can’t work legally. A lot of my friends are robbing houses, robbing the ice cream man. I dabbled in certain things I shouldn’t have been doing. I had friends who were going to juvenile hall, and I’m like, “Oh, I ain’t going there.” [Laughs] So, I just started looking for a thing to have so I could make money in a not-too-illegal way. The shirts were trash. They weren’t great designs. But I think most people who knew me when I was bouncing through high school bought something.

This is an unexpected trajectory into the work you’re doing. Did it feel different to sell something you had created as opposed to selling candy?

Yeah, for sure. Unexpected too, because I’d come to school, and people in my class would be wearing the shirt that I had just sold the day before. I didn’t realize it until right now, but yeah, I did like that feeling.

That brings us to architecture. Walking into spaces that emerged from your brain into life sounds like it could be the next level of that feeling. Tell me about going to college and the discovery of this professional path.

I went to school at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, right outside Philly, which is the first degree-granting Black college. I still didn’t know about architecture at that point. When you’re the first person to hit college, you have no clue what to major in. I was undeclared my first year and then ended up being premed ’cause I was like: “How do I make money out of here? Uh, I guess I’ll be a doctor.” [Laughs] That’s first-generation problems. I was not great in school—I had a lot of stuff going.

Year two is where I started to look at different creative mediums. I was painting and building more and looking at making my own beds and desks and things like that. But I don’t think I really discovered architecture as an option until I graduated. I didn’t discover it or go into architecture

school until I was like 23.

I was working in the medical field and just hated it. [Laughs] I was thinking, “How do I get back to what I liked—the creative, entrepreneurial things?”

I went heavy on researching something that I could possibly see myself doing for a substantial amount of time. I watched this TED Talk by this doctor who went to Africa and built this hospital. After that, I started looking at how to prepare a portfolio, looking at schools and stuff in my immediate area. I put together this random, random portfolio with a bunch of just—shit. I think it was probably my letter to them that helped me get in.

Architecture is not a shallow-end sort of profession. You were diving into the deep. What did that letter say?

I explained in the letter how this whole time I’d just been trying to figure it out and navigate. And now, I got to this point where I was finally making enough money to be okay. I had never been okay financially until that point. I’m like: “All right, my money’s solid. But I hate this. And I just can’t continue.” At that point, I knew that I just felt I was here to create, but I didn’t know what. I didn’t know that it would turn into this, today.

There’s an honesty in there that’s refreshing. It makes people want to pull for you and create opportunities.

I mean, I guess so. [Laughs] Once I started understanding what portfolios were meant to look like, I was just like, “Oh, bless these people because they should not have taken what I sent.”

Your real introduction to the architecture field was an article that you wrote about your experience as a student—particularly as a Black architecture student—at Woodbury. Is that right?

Yeah, for sure. I was mad at the moment. We were in a pretty small class at the time, probably five or six of us. Everybody’s work is pinned up on the wall, and the professor starts doing these comparisons like: “You could be like Frank Gehry. You could be like Eisenman.” And he gets to me, and he has this pause then: “You could be like Obama. I don’t know any Black architects.”

I did that day’s assignment normally, but then I added on a page of quotes from different Black architects, designers, artists who were speaking about moments of isolation. The professor apologized, understood what they did, and suggested that I write about it.

I did. It turned into something I wasn’t expecting. [Laughs] It got to the point where I was being invited to diversity conferences and all this stuff that I wasn’t necessarily ready for. I’m in school, my second year—I don’t even know the game yet. Then I went back to doing my normal schoolwork, and it wasn’t until my thesis that I began trying to figure out how to get the Black community represented through the built environment. I don’t think that it was connected purposefully for me, but maybe it was kind of a domino effect.

In your thesis, you talk about the idea that when people migrate to a new country, they bring cultures and customs with them, re-creating an aesthetic that reflects their values and their homeland. But you also point out that until 1968, Black people were not allowed to own property in LA, and the aesthetic most commonly associated with Black spaces had been imposed on those communities from the outside world. When did that awareness on the way that Black spaces have been distorted emerge?

There are two projects that I saw at this point in the thesis research phase. Germane Barnes had a project in Opa-locka, Florida, that was just so different than anything I had ever seen. It’s a heavy Islamic community and aesthetic down there. Germane is trying a community-based design, “designing against displacement.” And Destination Crenshaw, an open-air museum and community space along Crenshaw Boulevard in Los Angeles, which launched saying they want a design that’s unapologetically Black.

And I can’t talk about a book more than I talk about Spatializing Blackness by Rashad Shabazz. He speaks of the social and mental effects around the things like redlining that led up to what my thesis is based on.

One of the things that I find fascinating about your work is that you sit in this balance between the past and the future. As you think about the expansiveness of being “unapologetically Black” in terms of the architectural design process, what role does that time span play in the work itself?

Kind of a big role because I try to touch on different times. In the design process, even with the art I’m looking at, you’ll see an Afrofuturist image, and then you’ll see Ernie Barnes, and then you’ll see Kehinde Wiley. It’s just different times, different thought processes, and they all look very different. I think the architecture will be like those three influences. Nothing will look alike—yet it’s all Black.

Which tools from your education have you found useful and which have you rejected?

I’m so bad at trusting my own design instincts, and that may just be because during school, when I would try to make a more intuitive design decision, it wouldn’t really be accepted. In architecture, they’re like: “No, no, no. Show me the process. Show me how it’s unfolding to get to this point.” That’s a big thing. And part of me was like, “If I have to make up a fake thing, then what’s the point?”

I know a lot of people, they post-rationalize it. I am feeling the art or listening to music and something hits me. And sometimes you don’t know how to explain those things. This core of architecture is that they need to be able to see the process … and I kinda reject that. I don’t have to post-rationalize. That’s why this design studio is called OffTop because it is a slang term that means “without even thinking about it.”

Demar draws inspiration from the surrounding neighborhoods and the people who inhabit the space, looking to evoke the sense of home in his designs.

Tell me more about your ideas for the studio. Architecture’s business model tells you you’re just chasing after projects. You don’t do anything unless you’re commissioned.

I just hate that idea. With OffTop, I set it up on a structure where 20 percent of all the money that comes in goes to funding our own projects. We’ve already been dipping our toes in development and buying land and making plays that way. It starts with very small things like these pop-up parks that we’re working on and small installations.

But I understand how sick this game is now. I got offers where it’s like: “All right, we’ll give you 15, 20K to do this. Do your Black aesthetic thing.” And they don’t wanna put me on a design team; they want to make another role. I’m just not one to play those games. You gotta do it until you’re financially sound enough to not have to. So with this 20 percent thing, hopefully, it turns into: “I take a project if it speaks to me. But otherwise, they are going to be my projects.”

Demar, it feels like you’re back at the end of that first day of selling candy bars. You’ve realized that the Milky Way bars are trash, and you now know the rules. You’re like: “I know how this works now. I’m not going to give up 50 percent to that guy who’s selling terrible candy.” Now that you know the rules, you can break them, on some level.

Yeah, yeah. Exactly. That was perfect. [Laughs]

You talked a little bit earlier about some of the burden writing that article put on your shoulders. Suddenly people are calling upon you to have perspectives on things. What is that like now that you’ve recently graduated?

So many things that I’m stepping into, I wouldn’t be dealing with it businesswise for another 5, 10 years in terms of standard architecture paths.

I was trying to apply for jobs before at these firms that wouldn’t even give me a reply, and now I’m in the room with their CEOs, and they expect me to have answers to certain things.

But I feel like the most weight and the biggest burden comes from making sure that I don’t go out of bounds or against the grain for my culture. Some of these projects want me as a diversity hire. I already knew that was going to happen. It’s like figuring out what people want from you or for you and even what’s acceptable to take by community standards.

That’s just the game. In terms of mental health it is tough to figure out how to take care of yourself and deal with this sense of pressure. This pressure is a privilege, but it is taxing mentally.

I have read and thought about a single sentence from your website over and over again, “Every community deserves to be proud of the built environment around them, and the built environment around them should be based on the cultures of the people who live there.” Do you feel like that’s the legacy that you hope to build?

Yeah, absolutely. I’ll be happy if that’s the legacy I left [Laughs]

A lot of people think that the Black aesthetic is a continuation of the African aesthetic, and it’s just not that for me. I think there’s a very unique lived Black American experience, and that’s the one I’m trying to speak to. And a lot of times, we kinda have this code of how we speak and certain movements or gestures. It’s like slang, almost. And I want the buildings to speak to that language.

Most people who I know can’t go to the continent and find their family or know where they come from. A lot of us dealt with this migration. I think the Black aesthetic should speak to the spectrum of Blackness and everything that’s inside of that. When you do speak of, say, an LA Blackness or a Philly Blackness or a New Orleans Blackness, everybody’s Black is different. We have subcultures. But most things we can all look at and be like, “I see it.” That’s really what I want for buildings or for the installations—a Black kid can walk around and see themselves reflected.