Can you paint a picture of your childhood? How did it influence the way you think about creativity?

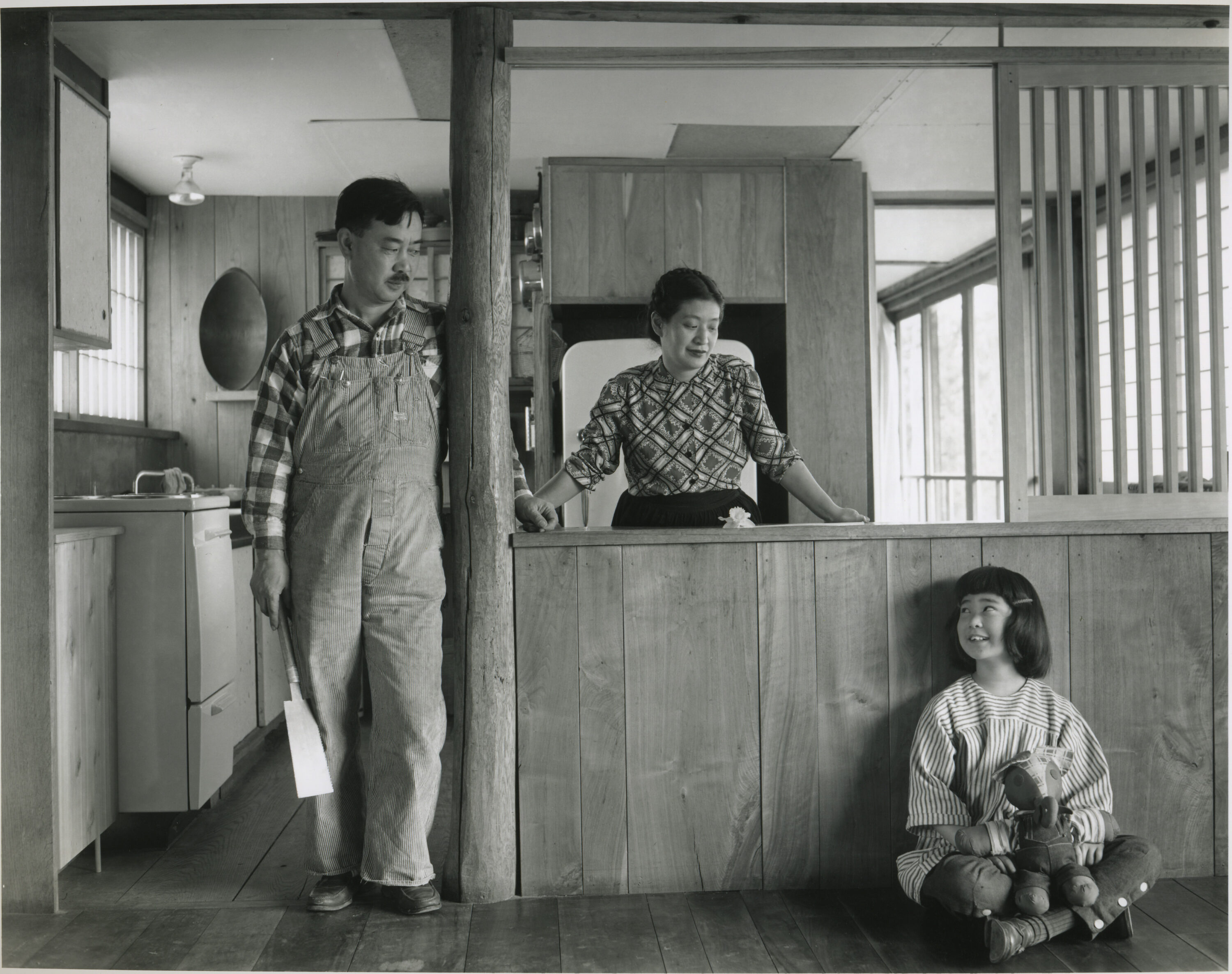

I was born in 1942, in Seattle, Washington, just before all the Japanese Americans on the West Coast were incarcerated. We were trucked off to the desert, without proper plumbing or housing or heat or food or furniture—anything. Luckily, I don’t remember all that. But Dad was put in charge of trying to make our barracks more livable. He was working alongside a Japanese carpenter [Gentaro Hikogawa] he became friends with, and that was one of the best experiences of his life. In Japan, he wouldn’t have been allowed to work with this master carpenter, he was too good. But in the camp, we were all thrown in together. There were old packing crates and boxes, and leftovers of construction materials to make furniture out of. We were in the Idaho desert [at Camp Minidoka], where something called bitterbrush grew. A lot of the residents used it for firewood, but they decided it was beautiful and that they would prepare it and respect its form. So, he not only developed the refined techniques, the use of tools and the kinds of joinery and so forth, but he also learned to make do with what we had, which wasn’t a whole lot.

How long was your family incarcerated at the internment camp?

Dad had worked for Antonin Raymond, the Czech architect, in Tokyo in the 1930s. Raymond had left Japan in 1939 because of the war and settled in Pennsylvania. Dad had gone to MIT, so his professor at MIT found out where we were, and he contacted Raymond and said, can you please employ Nakashima so they can get out of camp? That’s how we got to Pennsylvania; I was two years old. My parents were just so happy to be free again. Dad couldn’t do architecture because of the war, but he was even happy doing chicken farming.

He continued to improvise with found materials. He made some furniture at the Raymond farm out of old barn doors and pieces of lumber that were lying around. There was an old milk house that he adapted as his little shop. In ’45 when the war was over, he found a cottage down the road from where we are now and he worked out of the garage. He didn’t have any money. He’d been introduced to Hans Knoll by Mr. Raymond so Dad designed some pieces for Knoll and made the prototypes in his shop. They gave him a commission on each piece that was sold. There was a studio in New York City that also sold some of his pieces, and we survived. Then Dad found the property where we are now, just a few miles down the road. He asked the owner if he could have three acres of land to live on in exchange for labor on the farm. So we lived in a tent for a while. He built the shop first. He needed a place to work while we were living in the tent. Then we lived in one room. That was all that was done. We had a fireplace, which was the only source of heat. For drinking water, we’d go visit friends and neighbors with an empty jug. So we lived very frugally for many years.

Was your dad making furniture before your family’s experience in the camp? Why did he shift his focus from architecture?

Oh yeah, Dad started his little workshop in Seattle. The reason he went into furniture is that he went on a tour of the West Coast and he saw a Frank Lloyd Wright building being built, and said, “This is supposed to be one of the most famous, wonderful architects in the world. They’re just banging things together with two-by-fours and then putting this pretty facade on it.” It looks like a nice piece of architecture, but it is just shabby construction. You learn the Japanese way of construction in Japan. And he thought, If that’s the way they’re doing architecture in the USA, I’m not going to be an architect. That’s when he went into furniture. When he first started, everything was straight lines, very linear. After the experience in the war, he began to think more in non-linear terms.

Seeing your dad being so resourceful and making things when you were growing up, did it strike you as a creative path or as something purely practical?

I don’t think I thought it was an art form. Of course, when I was little, I didn’t know the difference between art and architecture or earning a living or making art. It was all the same to me. When Dad was in India in the ’30s [as the project architect for a Raymond-designed ashram dormitory, India’s first modernist building], he became a disciple of Sri Aurobindo, and he believed in integral yoga. Part of that integral yoga is not splitting yourself into pieces. He was intent on making his life and his work the same, so he always worked next door or in the house. I thought that was the way everybody worked. When I was little, Mom used to send me out to play in the shop. We never had TV or anything. And I was an only child for 13 years, so I had to keep myself amused. I used to go out and play in the sawdust and pick berries and leaves and make things out of them. I thought that was normal too.

Was it always expected that you would take over the business? Is that something your dad had wanted for you?

He didn’t say that. And I remember in the ’70s when one of his lawyer friends suggested he do some estate planning, he was planning to give everything to my brother. And the lawyer thankfully said, “We don’t do it that way in the USA.” So, they divided things pretty equally. But when I was little, I was underfoot in the shop all the time. The WRA [War Relocation Authority] came by to take pictures of me in the workshop just to prove that the incarceration didn’t do us any harm, that we were doing fine—it was pretty much a publicity stunt. My mother dressed me up in my best dress and she put ribbons in my hair and they sat me on the workbench using the tools. I grew up in the shop. When my brother came along, he got a TV and they got a fancy car and they had a house that had heat and stuff like that. My brother never went beyond high school, but I applied for college. I was thinking, I really like linguistics and music; that’s what I wanted to major in. And Dad said, “No, you’re majoring in architecture.” So I majored in architecture.

When I graduated, he sent me to Japan on a tour with Alan Watts, one of the first people who really translated Zen Buddhism into American terms and propagated it. He took us to all these temples and different places and told us about the background and the kind of Zen Buddhism that was practiced there—why the garden was this way and what the architecture signified. That was a really good introduction. Then I went to Waseda, a private university in Tokyo [for my masters]. My classmates all wanted to learn English, and they helped me with my Japanese. They’re still really good friends. I married one of them, he was a wiz draftsman. Here I was not even knowing how to use a triangle and T Square. Not only did I have a language problem, I had this drafting incapability, so I needed all the help I could get. [laughs]

You mentioned your dad’s intention to make life and work the same. Is that something you practice as well?

Well, it is. And I think that was in my father’s plan too. [My then-husband and I] were living in Pittsburgh when we first came to this country, and Dad said that he bought some land across the road from Nakashima, and he was building me a house. And I thought, I’m not sure I want to come home. I kind of like being somewhere else, not under my parents’ thumbs. But my ex thought it was a good idea that we couldn’t pass up. So we came back [to New Hope] and I started working. I was basically at the bottom of the pile. I had to do what everybody else told me to do. And then if I finished up my office work, I got to play in the shop. I was doing shop drawings for Dad. As time went on, I got to do client drawings as well. But we still live right across the road, and whenever there is bad weather, I have no excuse for getting to work. Sometimes I’m the only one there. After my divorce, I married one of the workmen and we’ve been living there since 1985. We always come to work. No excuse not to.

I’ve read that your dad fired you more than once. What was your dynamic like? Why did he fire you?

Dad was proud of the fact that he was from a Samurai family, which is the warrior class. Maybe it’s just the age he was brought up in as well as the Japanese background, but he was very strict and nobody got away with anything in his shop. He’d sent me to Harvard. I was the first class of women to graduate with a Harvard degree. We were taught to be independent thinkers for four years. I always questioned authority. [laughs] Dad did not like being questioned. When I first came back in 1970, there was no health insurance whatsoever. There was no liability insurance. Dad didn’t want to spend money on that. I’d say, “I think it would be really good if we had health insurance for the men.” He’d say no. And then we had arguments about why it was a good thing and why it wasn’t a good thing. That was probably one of the incidences of getting fired, ’cause I had opinions!

Can you walk me through the process of creating a piece of furniture, in the Nakashima tradition, and did it change when you took over the business?

It used to be just Dad. Someone would make an appointment and come in and tell Dad what they wanted. And then he’d go out and spend quite a bit of time in the lumber shed and find a piece of wood that was right for them. He’d do a pencil drawing and we’d go from there. Nowadays, especially since Covid, we’ve done almost all of our work by internet and through digital photography. When Dad first passed, there was a three-and-a-half-year backlog because he’d had a big show at the American Craft Museum, and our shop was pretty small. People were willing to wait. Except after he died, there were a lot of people who thought, Well, nobody can do this anymore. There was a myth that the press put out that George Nakashima was making all this furniture with his own two hands, and of course, the two hands weren’t there, and the artist wasn’t there to sign it. So about 50 percent of the orders were canceled. I had some friends in the press who said, Oh, we’ve got to do something about this. My first friend in the press was probably at the Michener Museum. The Michener Museum wanted me to design a room, a commemoration of my father and his work. I did that in ’93, and the PR person there gave me so much press. It was embarrassing. But she slowly brought us back to life, and I’m very grateful for that. We’re still friends.

What has your experience been like shepherding your father’s legacy, while also carving your own path with the business?

I was trained under my parents for 20 years before my dad died. During that period, I was trying to figure out why he did things the way he did, so I would be able to assimilate that. I didn’t mind following in his footsteps, so I just kept on going. And then there were people like Evelyn Krosnick. She had a house that burned down to the ground in Princeton. It was totally furnished in Nakashima she had collected over 35 years, and she was devastated. Not only did she have to rebuild her house, but she wanted to rebuild all the furniture that was in it. And I said, “Well, you had this before, and Dad designed it this way.” And she said, “Yeah, but I want you to make something different, I don’t want something the same as George would’ve done.” She kept encouraging me. Simultaneously, there was a man named Bob Aibel who had a gallery in Philadelphia called Moderne. In ’85, he had his first Nakashima show, and he continued to have Nakashima shows. After Dad passed, Bob said, “You’ve got to prove to the world that you’re a designer in your own right. Create new designs, and I will showcase them for you.”

Your family life and your creative life are so interwoven and have been for so long. Are there advantages of that closeness? Are there drawbacks?

Oh yeah. I mean, [my husband and I] lived in Pittsburgh for four years when we first came back from Japan, and I was pretty happy there. That’s why I didn’t want to come back to New Hope. I was afraid that he would leave. And eventually, he did. But I have four children, and the last one was born in 1972. So, I just dragged him along to work with me. He was a good kid. I set up his playpen and his crib in the office, brought over all his toys, and worked. I didn’t realize how it had affected me until recently. I had a conversation with that particular child and he said, “It didn’t really seem like we were your first priority.” And I said, “Well, I was a Catholic. Your father was a Catholic. I did not plan any of you. You just came along. It’s not that I really wanted to have children, but there you were, so I took care of you. But that wasn’t my main occupation.” And my other main occupation was not being a good wife. My ex-husband was always upset. I was busy working and didn’t have dinner ready when he came home from work. It did affect our family life because I was not focused on the family. In my children’s era, you made a choice to have children or not have children. I didn’t have any choice.

I’ve never thought about it that way.

Yeah. Nobody realizes that life wasn’t always the way it is now.

Well, something else that’s changed quite a bit is technology. How much have you incorporated into the creative process, or is it something you’ve intentionally resisted?

In the mid-’80s, my father-in-law was with IBM, and I was complaining about all the paperwork we had. He said, “Oh, get a computer system and it’ll be much easier.” My dad was afraid of it. So we’ve been [using computers since then], but there have been so many technological changes and improvements, I’m really glad we have younger designers. My grandson’s working with us now, and he’s 20. Every time we get stuck, we say, Toshi, what do we do about this? [laughs] And then one of the other designers, he does some of the old standard stuff on the CAD system. I figure at my age, I don’t want to learn how to do CAD. I’d rather do the freehand drawings. I’m better at that than I ever would be on a computer. We still do our drawings by hand on a drawing board with drawing tools. I had a design assistant who went to some kind of show in New York, and he came back and said, “Ha, ha, ha they had a display of antique drafting tools, and they were just like the ones we use!”

What role does nature play in the way you design and make furniture?

Well, Dad’s background was quite different from mine. In college, he actually studied forestry before he went into architecture. But I think his love of trees developed when he was young. He was a Boy Scout and he did a lot of hiking in the Pacific Northwest. And he said he just loved being alone in nature among the trees and the birds and the sky. I didn’t have that experience. I grew up in Pennsylvania, and the mountains aren’t so high and the trees aren’t so big, and there are more people. And I wasn’t a Boy Scout, so I didn’t do all that hiking and camping that he did. But we have all this lumber we inherited from my dad. He would personally go out and select the trees and go to the sawmill. And he’d have something very definite in mind when he was milling the trees, whether it would be a tabletop or a coffee table or a bench or something else. He would mill it accordingly and in increments that you can’t get commercially.

We try to keep that in mind when we’re selecting wood. It’s just really fun to look for. Dad used to bring in the lumber and it would come truckload by truckload into our little lumber shed; they would unload it piece by piece and stand it up. And they’re still standing up in that shed. Some of them are probably still from Dad’s time. You get to know each plank of wood as it comes off the truck. I mean, it’s an inspiration. The new shed is stacked in boule form so that all of the slices of the same log are in the same form as they were when the tree was growing. We did go through a long process of trying to catalog them all in a computer database, but it’s easier, and it always has been easier, just to go out and look at it. In the old sheds where the lumber is all standing up vertically, it’s like going into a forest and we go in so often, it’s kind of like visiting old friends.

The way Nakashima woodworkers create is so slow and studied, incredibly different from the fast-paced way people manufacture these days. How does this type of craftsmanship fit into our consumerist culture and do you think it has a positive effect?

Thank you for asking that question. People wonder why Dad wanted to make furniture when he had his background in architecture. And I think the experience in the camp influenced him, but he basically went into doing things the way he did as a protest against the mass production movement. Maybe this is because of his experience at the ashram in India as well. He felt that it wasn’t just the design, but that the craftsmanship itself was really important, not just for whatever you’re making, but for human beings. I mean, the mother of the ashram who was in charge of the project [my father was leading] thought that the work should be done not by a crew of outside workmen, but by members of the ashram. And even though it took them longer, it would be a spiritual exercise in learning how to make something beautiful with the materials at hand. Dad called it karma yoga, the yoga of doing. He really felt that it was important not to lose our manual skills and our contact with real materials in order to remain human. I think nowadays everything is so dehumanized—not only mass production but instant connectivity to wherever, whoever you want in the world. Our shop now has a group of workmen who are extraordinary. They have all kinds of different talents, but we’re all bound together by trying to create something beautiful.

At the ashram in India, they believed that beauty is not a manifestation of the ego or one particular person, but it’s a manifestation of the divine. Human beings are just a conduit for that divinity. And the divinity is manifested in whatever they make with their hands. We use power machines for a lot of processes, but the final fitting and finishing and everything is done by hand. And I think it’s that touch, the human touch to the object, which gives it form, and it gives the object itself a life of its own. And I think that’s what’s special about our furniture, that it’s not just a form that’s made by machine, it’s made by human hands. Something of the craftsman goes into each object that comes out of our shop. And sometimes it’s more than one craftsman, sometimes it’s quite a few craftsmen who collaborate to do what we do. The spirit of the craftsman is really important.

Sometimes I go in the shop and I think, Wow, that’s really amazing. I don’t know if it’s shipped out yet, but there’s one book-matched English walnut table that’s made from wood that my father probably had harvested, and it had the root ball on it. Normally, they don’t harvest the roots because it’s hard—you have to dig them out of the ground and then make sure you don’t run into rocks while you’re milling it and so forth. But there’s so much interesting grain and so many forms, and the end of this book-matched English walnut table was just gorgeous. And it’s not anything that a human being would’ve thought up, but it’s just respecting the form that’s already there—making it better and polishing it and just trying to create something beautiful.