- Interview by Brandi Katherine Herrera April 10, 2018

- Photography by Ryan Essmaker

Allan Yu

- designer

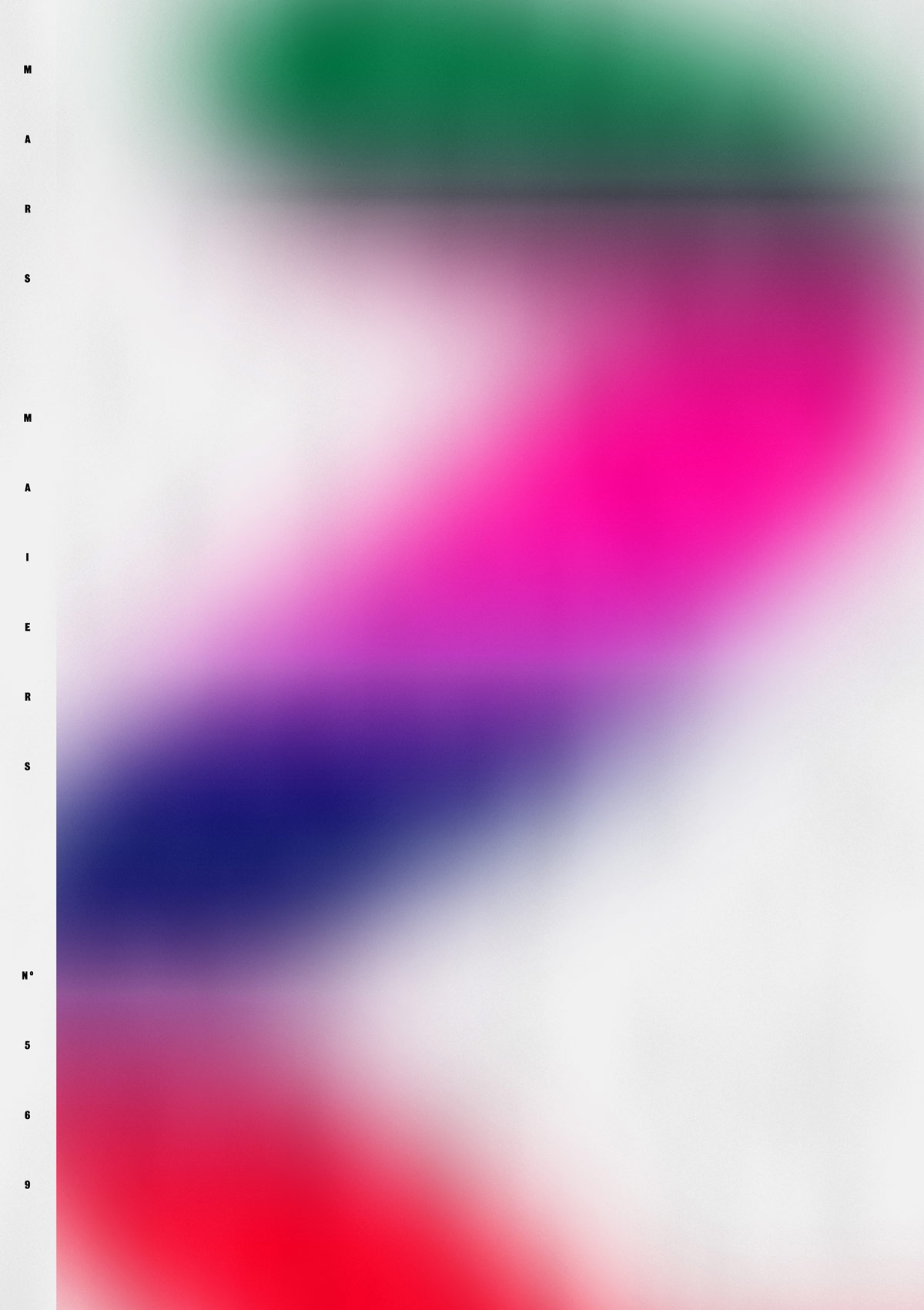

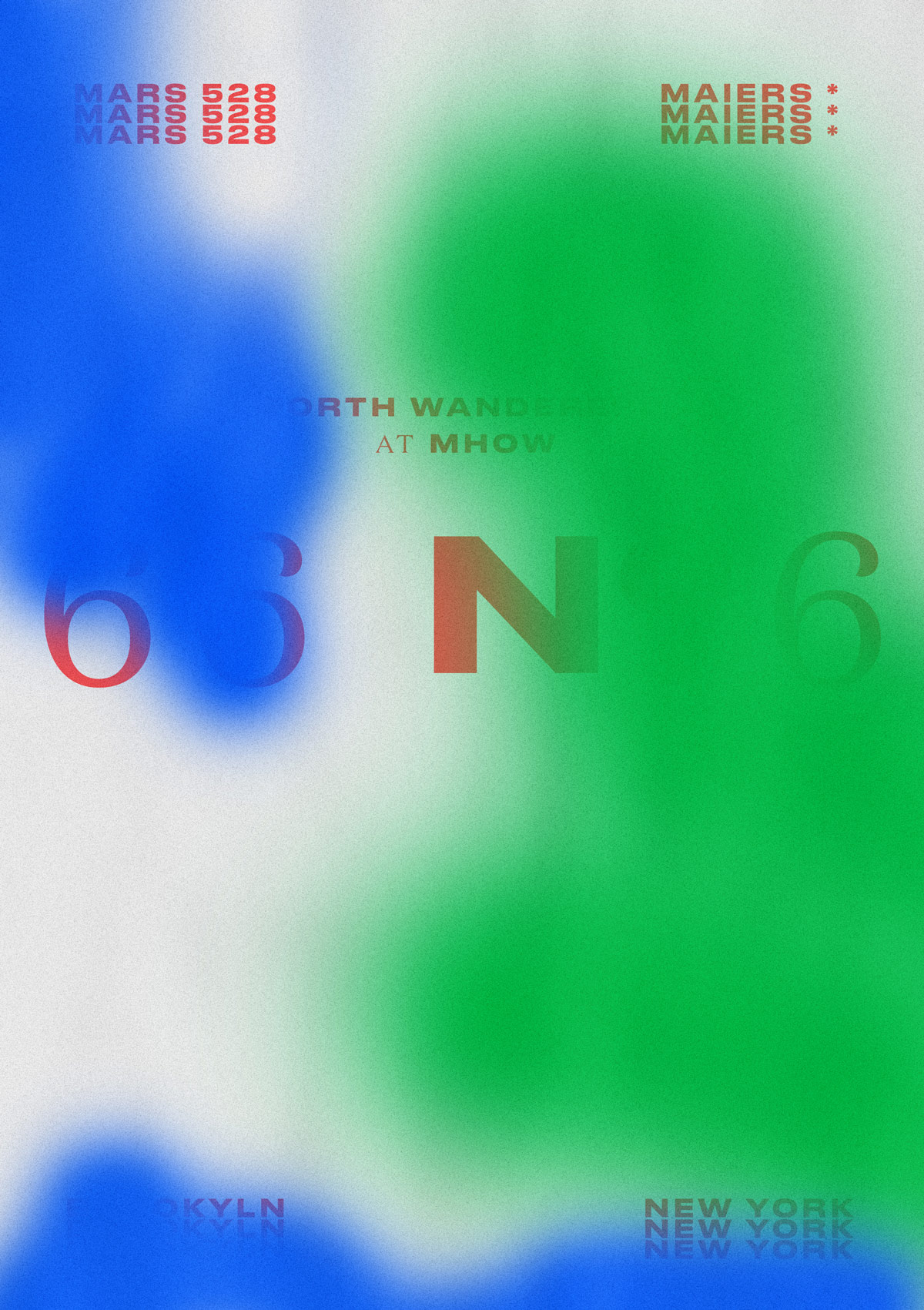

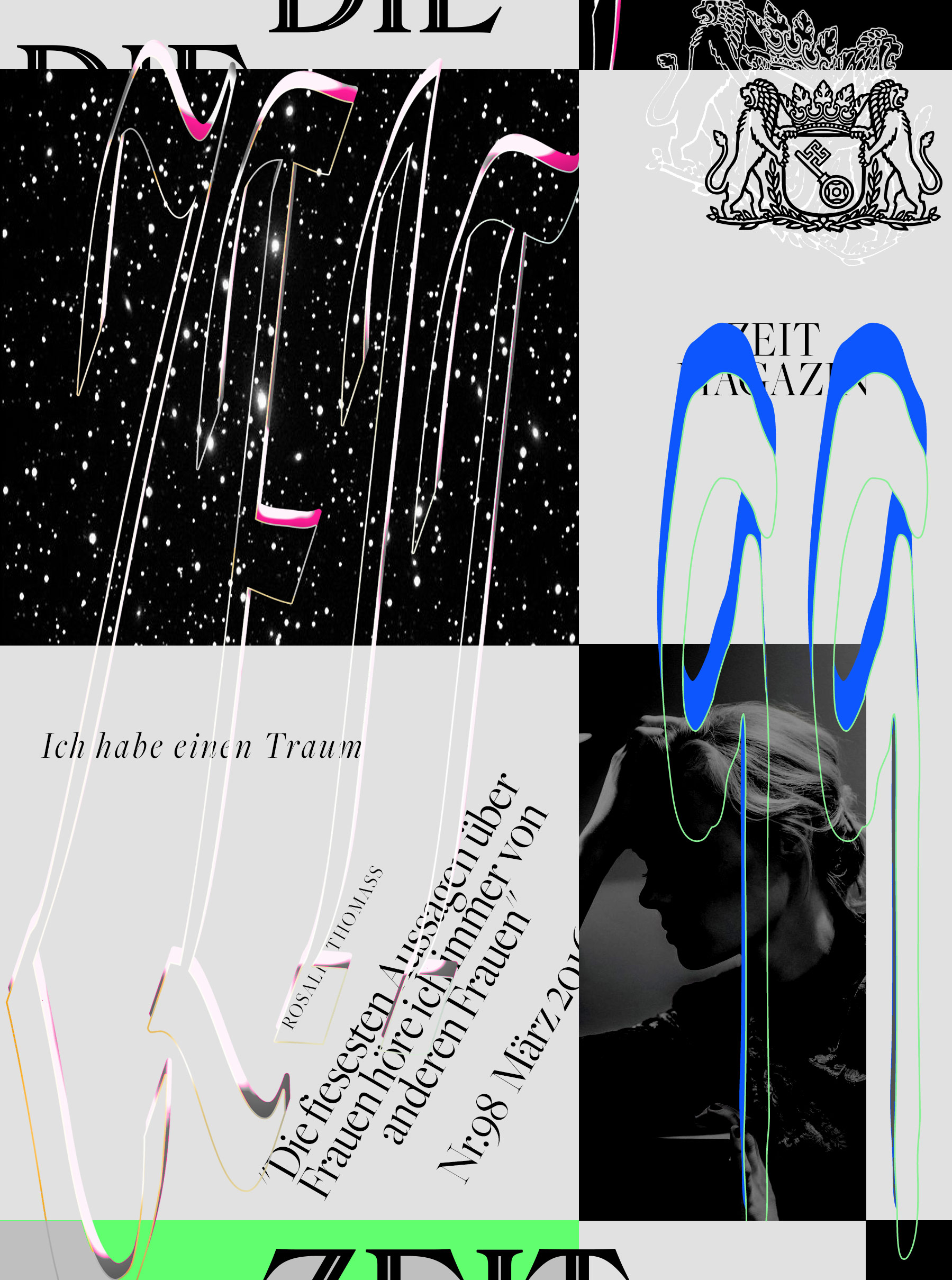

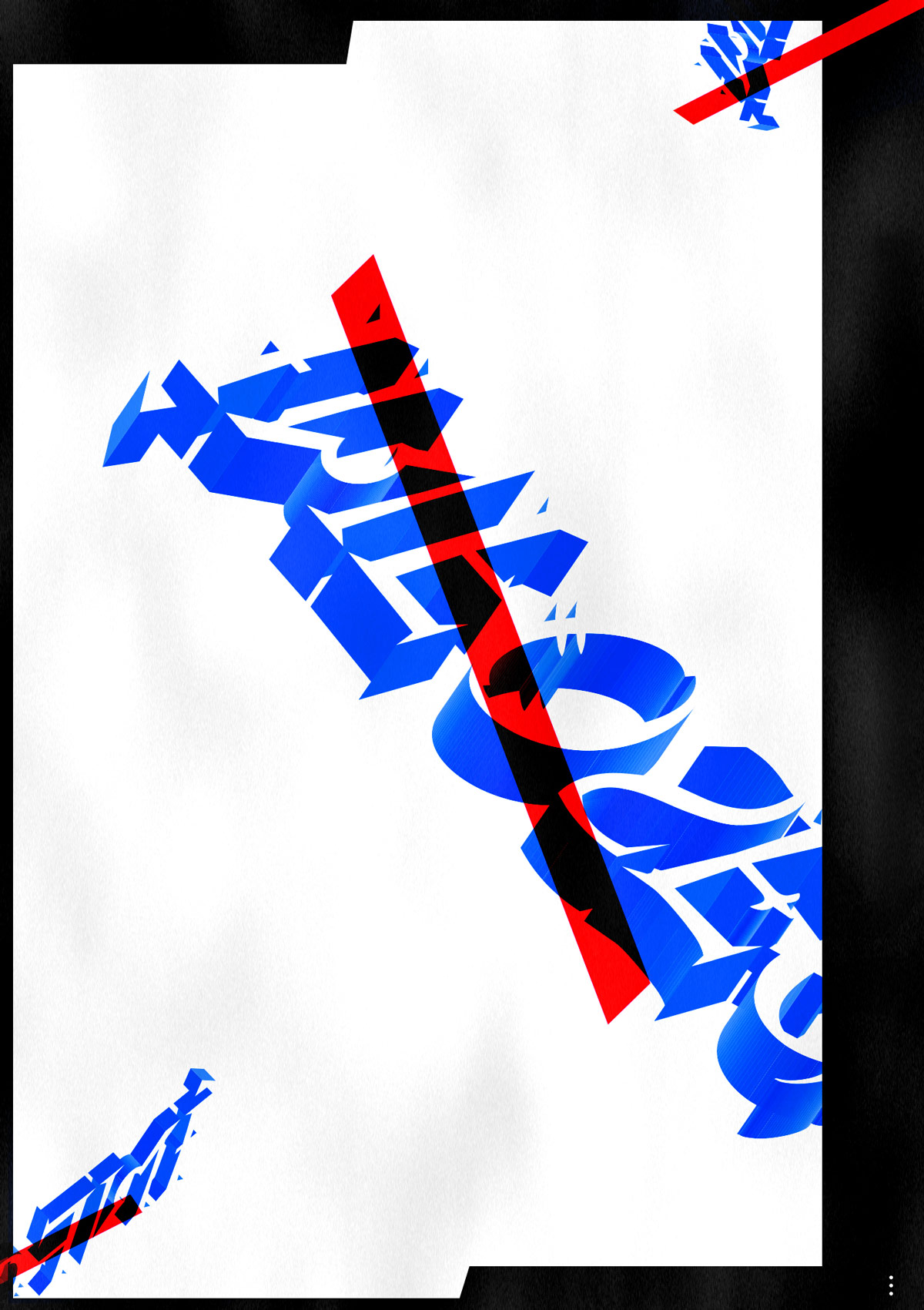

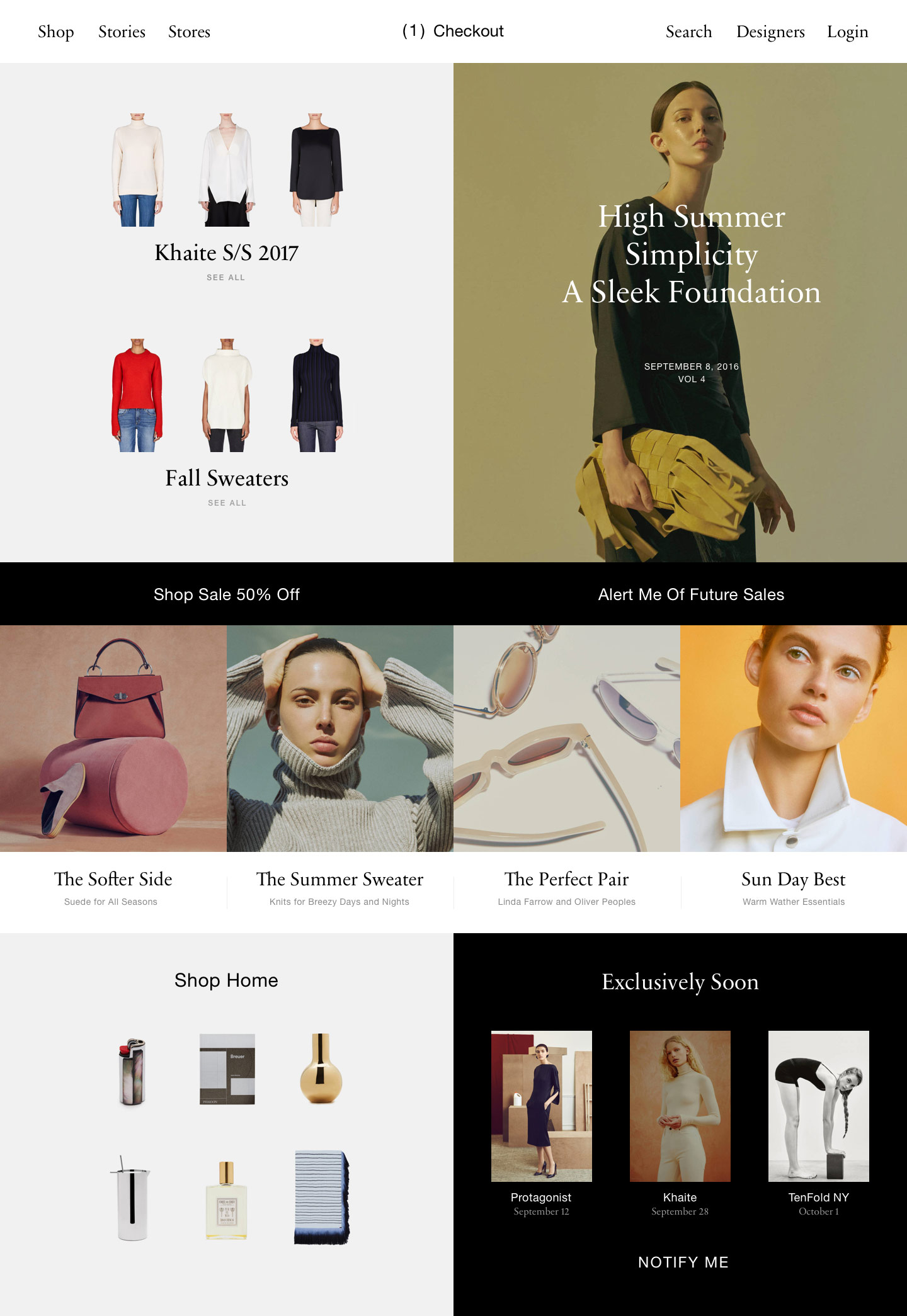

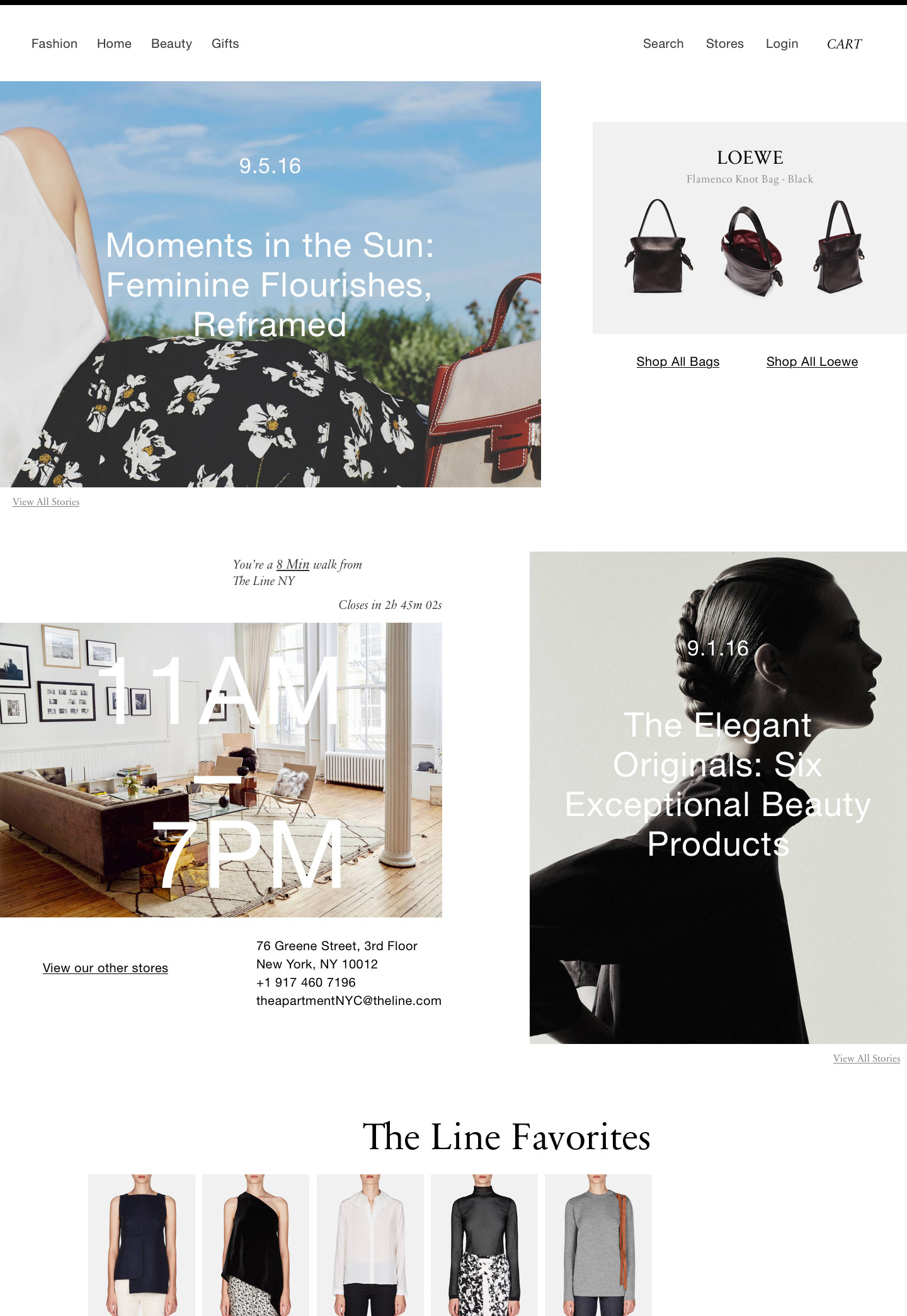

Allan Yu has felt creatively and aesthetically driven his entire life. But it wasn’t until he had gone well down the path of predictability—an education and early career in accounting—that he found the courage to finally break away from the identity his parents, and culture, had prescribed. With a client portfolio that includes the likes of Google and The Line, the Brooklyn-based designer has also observed a daily sketch practice over the past two years in order to confront his fears and to continue pushing himself in new, riskier directions. We caught up with him recently to talk about how failure initially fed that daily practice, Mars Maiers; about straddling the line between stability and predictability as a freelancer; and why self-forgiveness and coming to terms with his identity are two of the hardest things he’s had to tackle as a creative.

You lived in Boston when you attended Northeastern, San Francisco when you worked for Google, and you’ve been in NYC ever since you left. Where did you grow up? And, in what ways do you feel your upbringing may have shaped your ideas about art and creativity? I grew up in New York!

Oh, cool! So you’ve come full circle. Yeah, I returned home. I actually grew up in Brooklyn, and in high school my parents moved to Queens. New York has a real fast-paced temperament, so when I moved to San Francisco for Google, I couldn’t really vibe with the stereotypically lax culture. It was really sunny, and everything was nice, but I’m more used to the cold, and to a faster pace, abruptness, and rudeness. That’s the type of environment I thrive in, and the temperament I feel most comfortable with.

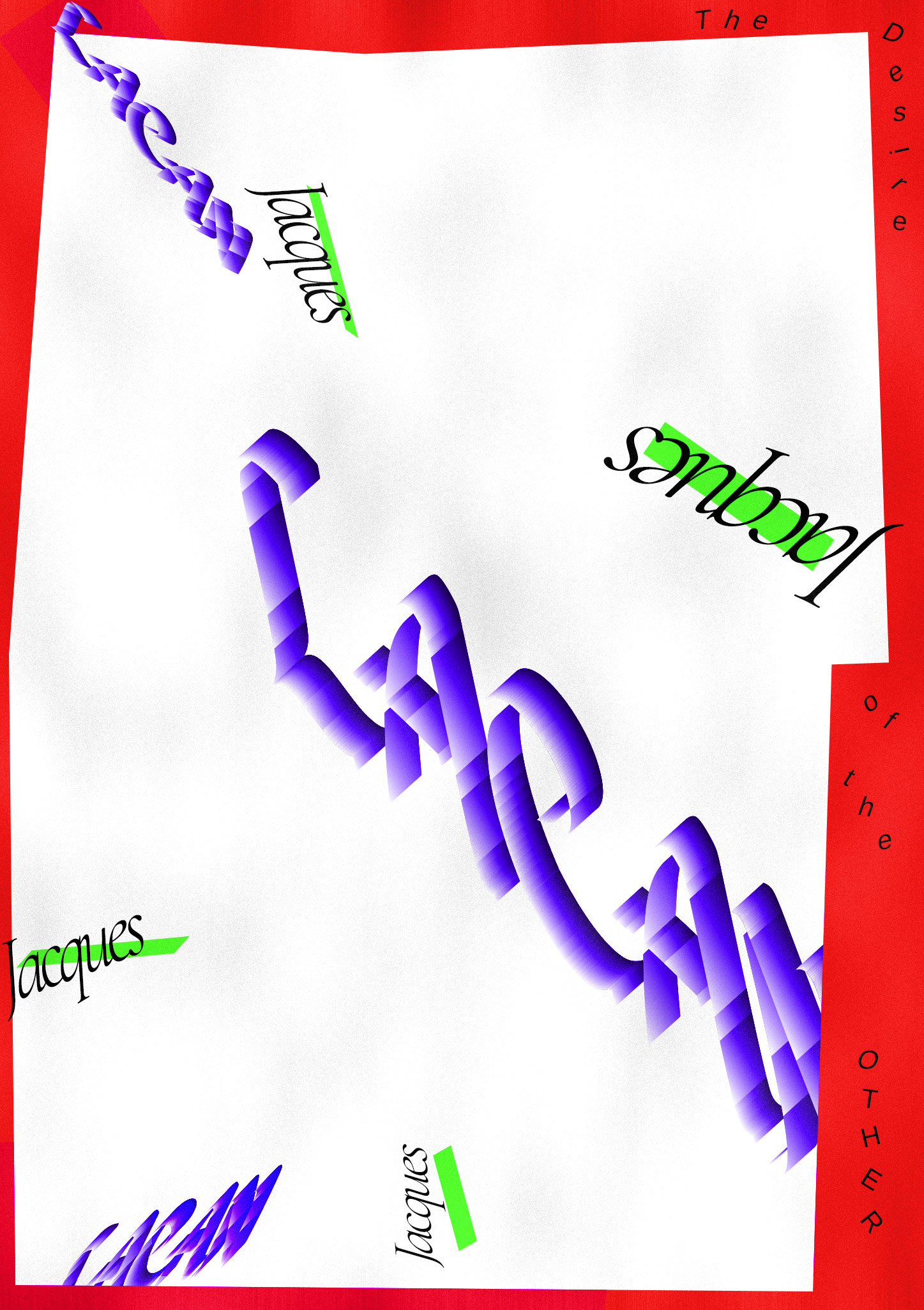

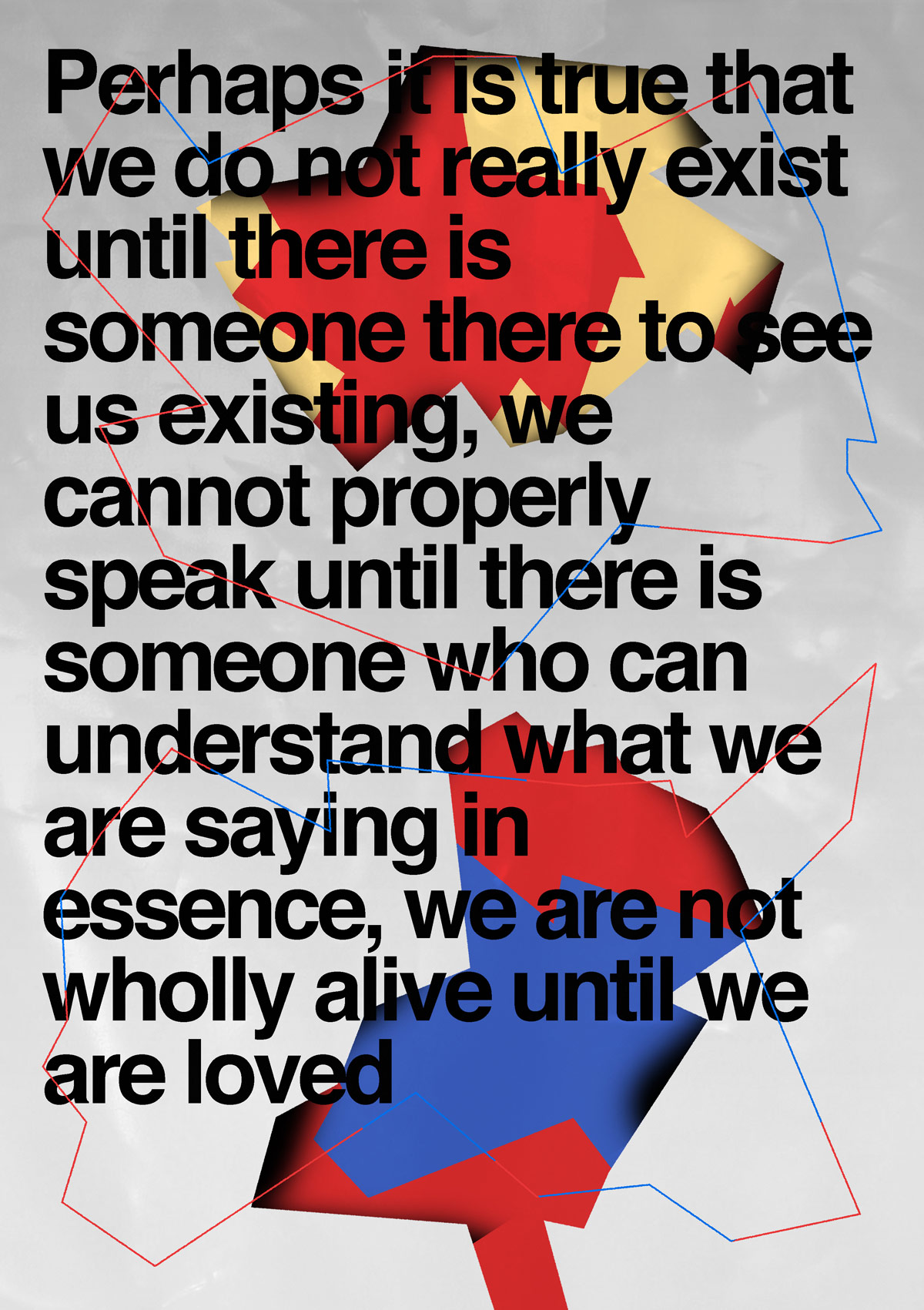

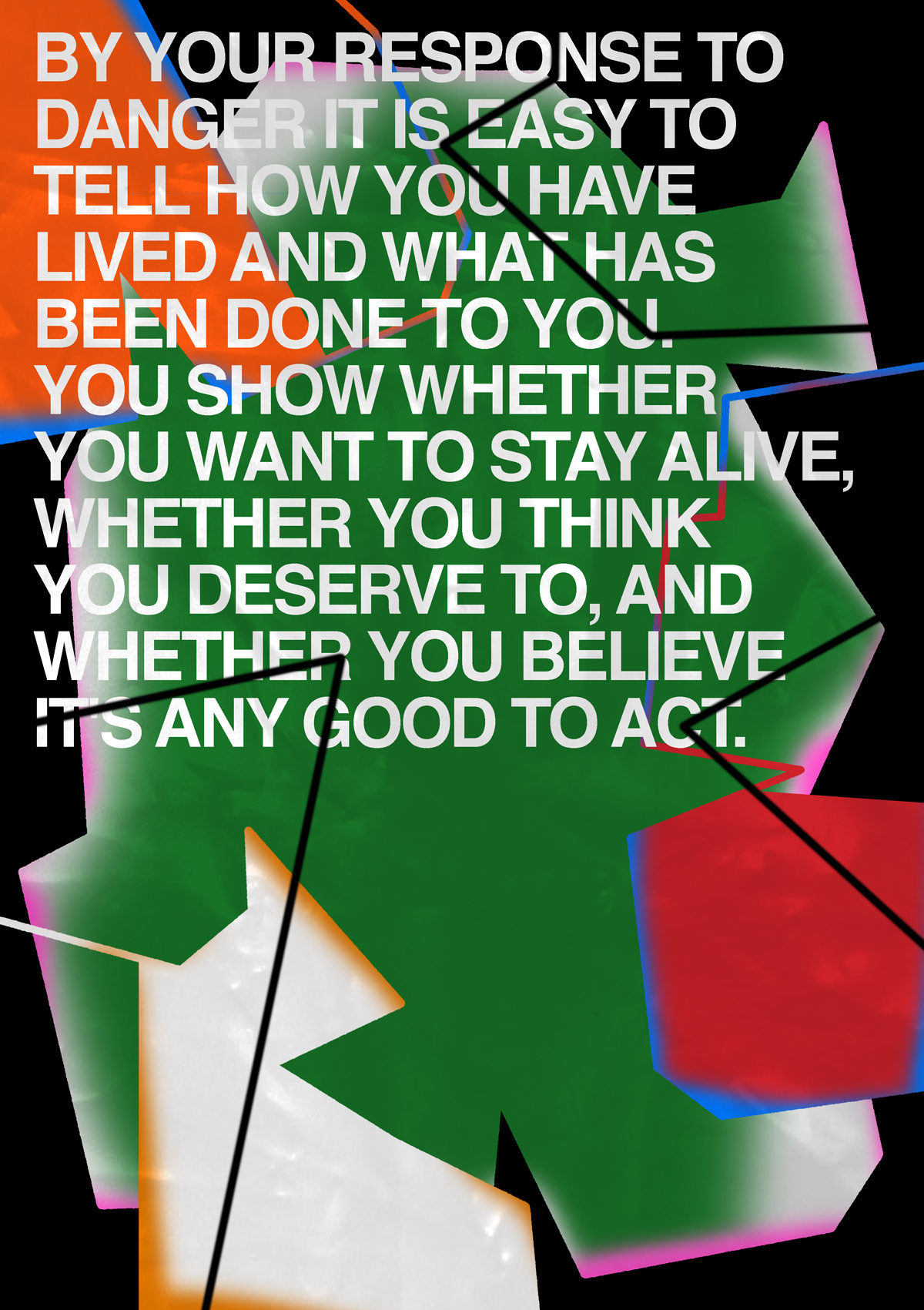

That East Coast urgency is something I think you see in a lot of my work, too. It’s fast. The colors I use are often just red or blue, because they’re the quickest thing to pick as far as a mouse movement goes. I also use a lot of scribbles, which have this sort of careless quality to them. Overall, I like to get into things quickly, and try not overthink them too much. I’m not sure if that’s good or bad, but I do know that when I overthink things, the work tends to suffer. Especially with Mars, my personal project, which is the complete opposite of the product design I do in my professional life.

That urgency you describe, and the quick movement and color scheme that characterizes it, is definitely apparent in the Mars Maiers project. Do you pronounce it May-heure, like the French word for “hour”? I say My-urs (laughing) I guess I just liked the alliteration.

I knew I’d pronounce it incorrectly! It’s really funny when you have to figure out the pronunciation of a fake name. Honestly, you can say whatever you want! I won’t be offended. (laughing)

(laughing) I’ll take your lead and stick with My-urs. Besides the name, there are a lot of differences between the product design you do, and your personal compositions. Still, there’s a real sense of forgiveness in the digital medium overall—whether the work is for yourself, or a client like Google. How does that room for error change the way you approach the work? The digital forgiveness is partially personal. In a way, it’s sort of like self forgiveness. But I think it’s also about economics. It’s more economical for me to make a mistake in Photoshop than on a piece of paper. In Photoshop, I can Command-Z the mistake, and there won’t be any consequences. Whereas, if I’m drawing on a piece of paper and make a mistake, that particular space is ruined. Depending on how far along I am, I may have to completely start over.

I’m not really sure if I’m that good at embracing mistakes when we’re talking about real-life work that has more consequence. It might take me four or five accidents to make a happy one. I’ve found the process of going one step back—redoing things by Command Z-ing—to be pretty helpful. In PhotoShop, I can also create five different layers, and move an accident around to see if it works in the composition, and feels more deliberate.

I think the forgiveness in my personal work just came with time, and quantity. If you’re only doing two pieces, those two pieces are going to mean a lot to you. But if you do 800, no one piece means more than another. So when I have a bad day now, I’m not going to be hard on myself for having drawn just a circle in a square. Because you know what? That’s actually okay. And tomorrow, I’ll do something else.

“…I like to get into things quickly, and try not overthink them too much. I’m not sure if that’s good or bad, but I do know that when I overthink things, the work tends to suffer.”

I’m happy you threw out the number 800, because I think that’s about where you’re at with the Mars compositions now, right? Yesterday was 800, so today would be 801.

Wow, congrats. That’s a hell of a lot of sketches. Thanks! (laughing)

You started the Mars project after having applied to Yale’s MFA program, and subsequently being rejected. You’ve spoken pretty openly about that experience, and how it felt like a personal failure of sorts. So the story goes, you began the project as a way of confronting your fear of failure, and to further develop your own voice. With 801 sketches under your belt, do you feel that it’s helped you accomplish the things you initially set out to? I still don’t know if I have a voice. But, I also stopped caring about that. I’m not even sure I need a voice. Some people have them, and some people don’t. I eventually just came to terms with that. With Mars, the style changes every couple of weeks—you’ll see a pocket of five different things that look similar to others, and then they just stop. I don’t really have one point of view that gets reproduced over and over. I have a variety of points of view, and I’m okay with that.

I also stopped caring about imitating other people’s work. Instead, I’m trying to figure out why they made the moves they did, and then see how I can apply those to my own work. If you copy everyone, you’re not really copying anyone, you know? If you copy one artist over time, then your work begins to look like theirs. But if you share a little bit of DNA with a lot of people, you become an amalgamation of them, which is something else entirely.

I don’t think I could get into Yale even today, with the work I’ve done on this project. There’s still no point of view. But I love the practice, and the ritual of it. It’s like waking up, brushing my teeth, taking a shower, making coffee—all of those daily routines people observe. When I began to look at it like that, my perspective changed. The real growth, though, has come from my realization that the Mars work is about me, and not other people’s approval of me.

“If you’re only doing two pieces, those two pieces are going to mean a lot to you. But if you do 800, no one piece means more than another. I’m not going to be hard on myself for having drawn just a circle in a square. Because you know what? That’s actually okay. And tomorrow, I’ll do something else.”

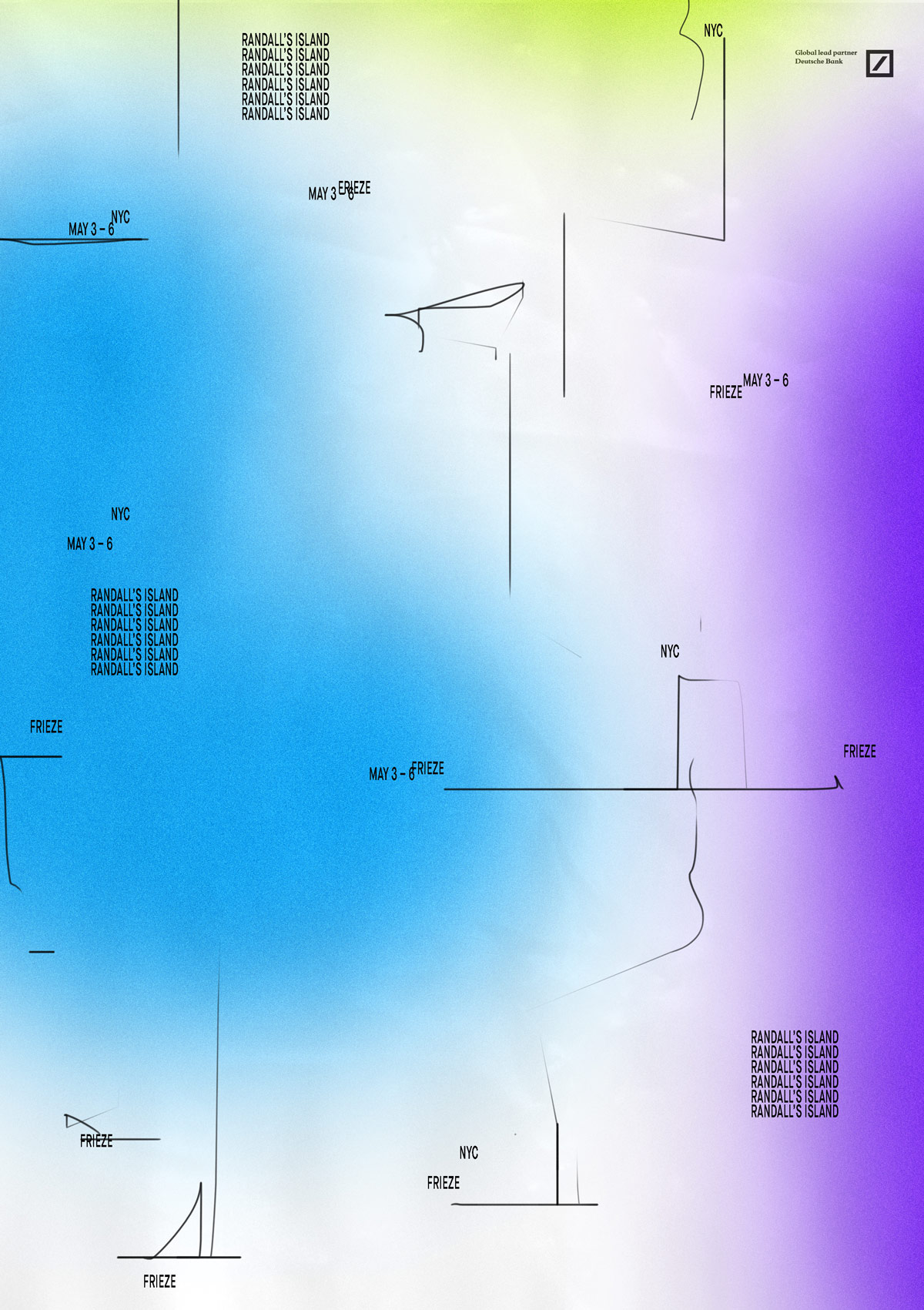

It’s such a freeing moment when you realize you can just stop caring about what other people think. I’m curious to know more about whose work you’re learning from as a result of the reverse engineering you mentioned, and what else you’re currently looking at or obsessed with. I often take one element or action from my life—something I see outside, or something gesturally that I’ve been doing, and happen to notice—and then exaggerate that just to see how far I can exhaust it before I get bored. Recently, I’ve been messing with drawing straight lines and curved lines in the same stroke. It’s something I learned by using my Wacom tablet; doing a Command-Shift move while drawing a line, and then lifting the pen up really quickly. As a result, you get these weird, deliberate-yet-accidental-looking straight lines and pull-aways.

In terms of who I’m looking at right now, it’s mostly fine artists, and not graphic designers. Lately it’s been Lucas Dupuy, Leslie David, and Michael Bevilacqua. Another favorite artist is Cy Twombly, which I think is probably one of everyone’s favorite artists.

Totally. He’s one of mine, too. What, in particular, about their work excites you? Mostly that it’s abstract line drawings, with great composition, which is something I really enjoy looking at. Artists and designers are a bit different. In general, I think designers tend to care more about negative space and composition, and artists are all about the object, the strokes, and the details associated with the techniques they use to create their work. I tend to focus on composition, and how negative space works. I really like white space—that sense of openness and generosity in a design and its elements.

And by generosity, you mean? Big gestures, big color spaces, simple lines that take up a whole space—those are the kinds of moves I’m attracted to, even if I don’t always used them. I like it when things look just a little less claustrophobic. So if I do pack a lot of elements into a design, I’ll try to make all of them either really big or really small in order to bring out the contrast.

I love how all of those artists use color, too, because I also enjoy using color in very particular ways. I had a gray phase where I only used that as a background. Other colors, when set against gray, react in really different ways. That was a challenging, but fun, couple of weeks.

“I often take one element or action from my life—something I see outside, or something gesturally that I’ve been doing, and happen to notice—and then exaggerate that just to see how far I can exhaust it before I get bored.”

What do you think you learned about how color behaves through that process? I don’t know, really. I think with exercises like that, a lot of what you learn is just muscle memory. It’s like playing basketball. All of these elements are forms of muscle memory that I get to keep building and developing every day. So when I’m working on a new piece, I don’t get so scared anymore. Even when I’m moving fast, I know how to shoot the ball. And that allows me to put my mind in other places, even if I can’t totally articulate what those places are.

Is that level of assurance in your own abilities something you think you developed more recently? In terms of confidence with product design, I think that came after I left Google. As far as the type of graphic work I do with Mars, I still don’t think I have the kind of confidence people might assume. I was once given a Mars project as a client project. It was a band poster, and I had a really hard time with it—the composition ended up being a lot more constrained and conservative than I had planned. I have confidence in the Mars work when I do it for myself, but with a client, I start questioning everything. Like, is this really what they want? Which quickly turns into thinking I’m not good at anything, and it all gets really depressing, really fast. (laughing)

The downward spiral! All too familiar. Yes. So any confidence you might think you see in the Mars work is limited. The moment it’s outsourced for a project in the real world, I feel like I can’t do it anymore.

That makes sense. Even when a client says, “Hey, just do that cool thing you already do,” and there’s all this supposed freedom, the intended outcome has still changed. That scenario seems more challenging than just executing on client work, period. For sure. I’d rather be able to say, “Give me xyz parameters, and I’ll give you an xyz outcome within this amount of time and budget.” I’m much happier with that kind of structure in a client project than anything else.

“I’m not even sure I need a voice. Some people have them, and some people don’t. I eventually just came to terms with that.”

That leads me to something I read, where you said that it was far easier for you to develop an aesthetic within a company’s existing design paradigms, but that your own personal aesthetic isn’t something you feel strongly about. What is it about working within the space of a client project that makes the process so much easier for you? I think it’s about emotional removal. It’s easier when you have a client project, because they give you an identity to work with. Whatever the product is, it has an intended purpose. You know who the client’s audience is, and how the client is talking to that audience. Your mission is to execute that even better, so that it’s even more clear, and has more value. That’s easier to do when it’s not about you and your own work.

I think some of the best artists and designers really know who they are. They have an opinion and a sense of conviction in themselves that I respect, and I don’t think I ever learned how to develop that myself. Part of that comes from being Asian. You have all these ideas of who you are that your parents prescribe to you, which prevents you from finding your own voice. When you finally realize you have the freedom to transcend that kind of prescription, you’re sort of at a loss. If I had a better idea of what my point of view and convictions were, I don’t have a doubt in my mind that I could execute something more personal for a client. It’s hard to figure out who you are. I’m going to be 30 years old, and I still don’t know!

I just turned 40, and I don’t really know who I am. (laughing) Honestly, I don’t know that we ever totally do—especially creative people. I think everyone who says they do is just faking it. They’re definitely faking it better than me! (laughing) The hardest thing to come to terms with is always yourself.

“Big gestures, big color spaces, simple lines that take up a whole space—those are the kinds of moves I’m attracted to, even if I don’t always used them.”

It’s true. Taking a really hard look in the mirror is frightening. What exactly was the identity your parents prescribed to you? And how does that play into the fact that you chose a pseudonym for the Mars project, rather than more blatantly connecting the project to your personal identity? The prescription I described is pretty traditionally Asian American. It’s all about academia. You know: be really good in school, and major in business, medicine, engineering, or law. Then climb your way up the corporate ladder, bring home some grandkids, and you’re good! I was always a visual person, and aesthetically driven, but there was a real lack of support and encouragement around the liberal arts. I didn’t get the chance to explore that until much later, when I finally just said, “Fuck it, I’m going to do this.” I was an accounting major in college, so I did initially fall into the trap. It took working at Price Waterhouse for me understand that I hated that work and lifestyle, and that’s when I broke away from the identity that had been prescribed by my parents.

As far as Mars goes, I’m a pretty sensitive person. I thought that if I put work out there under my own name, it would be criticized within the lens of my product design work. It also didn’t feel like I could give myself a clean slate. I wanted to start over, and lean into this idea of not having an identity at all. So I created a new one.

In doing so, do you feel like you’ve taken on the Mars identity, whatever that is? After doing so many Mars compositions, part of me wants to associate my name with the project a little more, just to see what people think. You get to this point where you just kind of want to know. So lately, I’ve been tying my name to Mars more closely.

How did your family feel about your shift from accounting to design, and claiming more of a creative identity? When I switched majors to graphic design, my mom was actually pretty supportive. My dad was a little bit more upset. He would say things like, “How are you going to make any money so you can eat? What kinds of jobs do graphic designers even get? Are you going to make billboards?”

I got really lucky, though. I fell into digital design, which slowly transitioned into product design. In the product world, there’s a lot more opportunity and VC funding. My parents are really proud that I worked at Google. I’ve never told them about Mars, though. I think it would be weird to tell them about how it all came about, but maybe I don’t give them enough credit.

“The real growth…has come from my realization that the Mars work is about me, and not other people’s approval of me.”

They would never just look at your website and be like, “Wow, look at all these sketches!” They’d see the name Mars and think, That doesn’t say Allan, so it’s not our concern! Or they’d be like, Who’s Mars? Is that your friend? Or, Mars is so good! Why aren’t you as good as Mars? And that’s the kind of thing that triggers me. (laughing)

You said that when you were studying and working in accounting you realized pretty quickly that it wasn’t the life you wanted to live. Now that you’re a designer, do you feel like you’re living the life you had always wanted? Oh, shit. That’s a really good question. I don’t know! I guess I’d say partially yes, and partially no. There’s no way I could have envisioned the life I have now, back then. I have always straddled the line of not wanting to know exactly what my life was going to be, with wanting some form of stability. If you have a traditional nine-to-five job, you pretty much know what the rest of your life is going to look like, because you know the progression. You know what the structure is, and how to move up within that. I didn’t like that idea; where there’s a path to move up, and somebody else has already written it for you. I wanted a life that was less predictable, and also more exciting. Still, I’m not 22 anymore. I kind of like having some stability. Knowing I can eat tomorrow is nice!

Striking that balance between stability and predictability can be so tough as a freelancer. So, do you feel creatively satisfied? I want to get off digital for a bit, and I want to be a little riskier in my creative pursuits. Even Mars is kind of a cowardly move. I only took a risk with it when I knew I had enough work to talk about. That’s not a bold, confident person’s move. It’s a scared person’s move. So, no. I don’t think I’m creatively satisfied.

Fair enough. It sounds like some bigger risks are in your future? I’m working with Fictive Kin right now on a podcast player called Wilson, which is set to come out in May. It’s been surprising to see how some of the things we’re doing seem influenced by the Mars work. I’m using Mars today, actually, to test out some things for it. Putting that work out there for the world to see will definitely be a bigger risk for me.

“I wanted a life that was less predictable, and also more exciting. Still, I’m not 22 anymore. I kind of like having some stability. Knowing I can eat tomorrow is nice!”