Brian, you and I originally met through our work in the climate-art intersection and I remember we first bonded over a shared loathing of NFTs.

That’s right, yes. The NFT bubble was one of those bubbles that I’ve seen quite a few of now in my life. And for as much as 10 weeks I was being bombarded with letters from people every day saying, “It’s time to make your NFT! Come on, you’re going to lose out. Here’s the moment where you can pick huge fortunes of low fruit if you’ll only take advantage of it now.” And I just wasn’t very excited about it. The question I asked, and perhaps you did as well, was, What does this actually produce in the world other than more money? That was about the only result I could see. It was a way of becoming more of a capitalist than we already were.

And taking the worst of the old art model and the worst of the new digital era and economy and combining the two.

That’s absolutely right. And as we know, two wrongs don’t make a right. I came up with this idea that children learn through play and adults play through art. So what we’re doing when we’re making art, and enjoying it I think, is we’re doing a kind of grown-up playing. But again, if you say ‘playing’ people think, Oh, so it’s not really serious then. But playing is fundamentally the most serious thing that we do, because it’s in playing that we model different futures. We want to imagine what it would be like to live in a totalitarian state—we write the novel 1984. Or what would it be like to live in a future where we start to solve climate change? That’s the novel The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson. So what we’re doing is modeling other possible realities. That’s what art does for us. And it’s the most important thing that humans do. So when people say, “You’re just playing,” they’re missing the point: playing is very important.

When were you aware you were going to keep playing and not get a job?

I was very aware that I didn’t want to get a job. My dad was a postman, or mailman in American, and he changed shifts every week. So it didn’t occur to me until quite late on that it was like doing a flight to Los Angeles, staying there for a week then back to London and so on. His body must have been permanently trying to adjust. He used to take a thermos flask of tea to bed with him because he’d wake up in the night, have a cup of tea and a cigarette, and then go back to sleep. His internal clock must have been all over the place. I remember very clearly one night, him coming home and my mother putting dinner on the table in front of him and he was so tired, he fell asleep, into the dinner. He just couldn’t stay upright and I can really remember clearly thinking, I’m never going to do that, I’m not going to get a job.

And it was a thought that was possible to entertain at that time because the welfare state had just started up so you could get national assistance or dole. You could get a small amount of money from the government to keep going as long as you pretended you were looking for a job. Healthcare was free. Education was free. So, it was actually quite possible to conceive of living outside of the world of jobs and the routine of work and yes, I decided, I’m not going to get a job. I’m not going to do anything that feels like a job.

So I went through art school. Five years of free education. Best thing that ever happened to me. And I left and didn’t get a job. And I thought, I just want to stay open for something interesting to come along. And something interesting did come along. I had started experimenting with tape recorders and electronic music. And then, the group Roxy Music formed and I was part of that.

Yes, something interesting came along or you helped catalyze something interesting. But before Roxy Music you had all of these other experiments that you were doing that were beyond music—exploring the visual, the sensory, other mediums like light. Did those different worlds always seem like they were interconnected for you, that you couldn’t really pull them apart?

No, it was the opposite actually. The one thing that really worried me was that I didn’t know how all these things connected to each other. Even before I moved to London, I was very much into the avant-garde music scene in England. Not so much as a performer, but as one of the 30 or so other people who were interested in it. And so I used to come to London when I was at college or when I lived here and go to see whatever was happening including John Cage, Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff. And then there were of course English experimental composers like Gavin Bryars and Cornelius Cardew. I was really interested in all of that. And because I couldn’t play any instruments, and because much of that music didn’t require the ability to play instruments, I felt this is a place where I could do music.

At the same time, I was very interested in pop music, in rock music, whatever we called it then. And I could not see the connection. I couldn’t think of a way of connecting the two together properly. Well, that started to develop for me in the ’70s when I started to think that I could find a way of combining elements of both. But I was also working with light, which I had been doing since the mid-’60s, and doing quite a lot of new stuff with light. Light wasn’t a medium that many people were using then because it was very clumsy. So I was making things and I had no idea how they connected with music. I had all these different balls in the air and I had faith that somehow it would all make sense in the end. And it did. It still hasn’t made complete sense, but over the years I’ve started to realize that I’m working on one thing and it comes out in different forms but I feel that there is a project at the center of it all.

Because if we keep our sense of play alive and that curiosity to follow whatever scent or invisible thread, it’s amazing. Firstly, of course, because of where that takes you but also what we discover in the creation process. Human beings often lose their ability to play. We lose a lot of those child-like qualities as we get older, and as we get jobs, and become so conscious of behaving in certain ways that originality almost feels like something you need to fabricate rather than something that you find by going off and following whatever you’re into.

Yes, that’s absolutely true. The most important thing to remember is that you can’t help being original. Unless you constrain yourself into not being original. Every human being is original. But what you can do and what a lot of people end up doing is disguising the fact. They stop themselves from being original because it’s awkward or—

It’s safer.

Yeah, it’s safer.

You love the idea of complexity arising from simplicity because, and you and I have talked about this in religion, for a long time there was this idea that there must be a more complex being to have created all of this.

That’s the thought I disagree with.

Yeah, and so then to look at nature and to look at these very intricate systems, which have arisen from simplicity, is that something you were wanting to mirror through your work, through your art, and the different modes that you were presenting it?

Yes. I’ve always liked economy. The idea of seeing how much you could do with how little. That’s why Mondrian fascinated me, you could describe his pictures almost in words, they’re so simple. And I think that’s why doo-wop fascinated me as well, because it was just a bunch of guys singing, most of the time, without any instruments at all. So, I always thought how incredible that you can get so much from so little.

And funnily enough, we discussed play before, and one of my earliest games—I had a few games like this, but just to give you an example—I would dig a little hole in the garden, and then I would pick up sticks and the rule was that no stick would be big enough to cross the the whole of the hole, if you see what I mean. And then I would try to build a roof by threading them together and covering them with mud, which I allowed to set. So I’d make a sort of a wood and wattle roof and the test was that I’d then ask my dad to jump on it. It had to be strong enough to support my dad. Luckily, my dad was quite a small man but that’s the kind of thought experiment that alway interested me. Trying to set up a challenge like that: What can I do with this little material, can I magic it in some way, can I make it magic?

In a way, a game like that nods to your connection with nature and ecology. And the idea of simplicity and waste and how we have really been fed this notion of how we should be living—of course by corporations and a very capitalist system—that is completely discordant with the natural world but also the reality of what we actually need, because we don’t need like 80 percent of what we think we do.

Yeah. Well, what happened, I think, was when consumerism really got going in the early part of the 20th century it looked like liberation. Suddenly people felt that they had the freedom to buy all these wonderful different new choices of things and newly invented things and it was freedom in a lot of cases for a lot of people. But that appetite for consuming made a lot of people a lot of money, so there was a lot of attention spent to keep accelerating the rate of consuming. And it wasn’t really until about the 1960s I’d say that people started thinking, Do I really want all this shit? Is it actually making my life better or is it making it worse?

It was very interesting to me that Marie Kondo finally hit the bullseye a few years ago by saying a message that is profoundly anti-capitalist, which is basically, “Stop consuming. You don’t need so much. You’ll be happier without so much.” I think she’s very important in that respect. People laugh when I say that, but I think that idea of taking what was an art movement called minimalism or a religious idea called zen, taking that into ordinary life and saying, “This should be part of your lifestyle” was pretty radical.

I was thinking this morning about possessions and that sense of being possessed by something and how that’s a negative term. And how the more things we possess the more we are possessed by them.

Yes, and everything requires attention, that’s the main thing to remember. Every new thing you add requires attention and I think the most important resource in the world right now is your attention. That’s why huge industries exist to capture it. Facebook, Google, everything exists to capture your attention and to monetize it in some way. So, my message to everyone now is don’t get a job if you can avoid it and look after your attention. Really pay attention to your attention. Where is it? What’s it doing? How often in the day do you actually have time when your attention is not being taken up by somebody else or by something else?

We’ve got our phones with us all the time. I’m not a Luddite, I have a phone as well and I use technology, but I keep finding myself thinking I don’t give much time to my own self any longer. So I now am in the habit of going out for a walk and leaving my phone behind. The first time you do it you think, Bloody hell, that’s a bit weird to be outside without a phone. But then after you’ve been walking for an hour you find yourself having a lot of thoughts that weren’t in your head before. So my feeling is this, you are either in input mode, which means you’re taking stuff in like you’re eating, you’re eating the world in some way, in your brain. Or you’re in output mode, which is where the stuff that’s in you is coming up and has a chance of getting out to the world. And so I realized that I wanted to give more time to that second process of letting stuff bubble up from inside me.

I think you can also be in reciprocal mode, where you are within your environment and you’re responding to what’s around you but also within you. You’ve got the presence to really respond to the positive stimuli—not your phone!—because maybe there’s a story, there’s something that you’re meant to be doing there, you’ve just got to tune into it. Because our receivers are often so clogged up with all the irrelevant shit, which is also a distraction from the core work. It’s almost like a popularity contest that no one can win.

Yeah. What I find myself doing more and more is looking for unmediated experience. That means to say experience that hasn’t been packaged up and smoothed off and delivered in convenient, salable little chunks to me. I love that sort of thing. I love movies and I love books but for fuck’s sake, we’re eating non-stop, you know? It’s like we’re constantly in the kitchen, looking through the fridge, stuffing stuff into our mouth—that’s mentally what we’re doing all the time.

It’s like the character in Spirited Away, No-Face, who just keeps consuming but is never satiated. It’s like being consumed by needing to consume and then you forget what you’re even consuming anymore, whether it’s food or music or information, and then everything has to get more sugary to get your attention or more “shock tactic.” I think we’re just sensorily numb from all the information.

Yeah, we’re saturated and you’re quite right that the arms race is that it’s got to be more shocking. I really noticed this in American entertainment that the speed of edits keeps increasing. For instance, films and movies, the edits now are so quick. And you can see it if you just walk past a house. You see the color of the house is flickering, that’s the edits on the TV screen. And you think wouldn’t it be nice to walk by and see it change much more slowly, wouldn’t that be different?

Like Harold and Maude and that opening sequence. How long it is before the first cut, it’s beautifully slow. And again, you think how much can be conveyed with how little. It cost nothing to make but it’s good storytelling. There are a lot of things that will never go out of fashion and don’t need to be constantly updated and then yeah, there are some things that can benefit from an update every now and then.

Have you ever seen the film Victoria? That’s a single shot film. They shot the whole film between four and six o’clock one morning in Berlin. It’s a thriller, it’s a heist, and it’s so exciting to watch when you know this is actually real time that you’re seeing.

Something else that’s probably been commandeering a lot of your attention in the last couple years, but in a good way, is EarthPercent, the organization you co-founded to create a way for the music industry to donate royalties to the planet. What do you feel most buoyed by so far?

Some very interesting things have happened recently, which is that several really big philanthropic foundations have decided that they’re not going to try to exist for the next 100 years giving out grants to people. They’re going to turn it all into cash within the next two or three years and immediately put it into climate change so suddenly a lot of money has appeared and we really need a lot of money to address this because we’ve still got the coal industry fighting against it. We’ve still got a situation in America, fucking insanity, where weathermen or weatherwomen who refer to climate change are getting death threats.

Even an episode of Attenborough’s latest documentary series, Wild Isles, wasn’t played on the BBC. They wouldn’t broadcast it because they thought the episode’s representation of the destruction of nature would cause too much backlash.

Yeah, well, that film Don’t Look Up by Adam McKaye is quite interesting because it shows something that I’ve been seeing so much, which is as the evidence gets stronger, the resistance to it gets stronger as well, the feeling of, It can’t be true because I don’t want it to be. But as I say, a lot of these really big foundations are starting to think, We’ve got to put our billions into this, so that’s the beginning of some good news.

And in terms of the charity itself, what’s giving you hope?

We’ve started to build a community of people who are thinking about it. I think any solution is going to come down to communities of people forming and saying, “Let’s get into this together.” And that togetherness is, first of all, a joy—it’s not asking people to do something painful. It’s really a pleasure when you suddenly find common cause with people and you have a reason to come together and do something about it. And it’s working. There are so many communities forming all the time. My studio has become a sort of beehive of conversation and meetings and people coming together. So, it’s exciting. It’s exhausting, too. And it’s distracting. I can’t get much music done.

It doesn’t really work today because you’re wearing a blue shirt, but do you feel the fuchsia is bright, Brian?

Ha! I often do wear fuchsia shirts. I feel kind of a serious bifurcation. We either have fucked it all up and it’s the end for us, that’s a very distinct possibility. Or else if we succeed in getting through this, we will have to change so many things for the better. We will have to treat people more equally because we need everyone on board to get us through this. We have to change our understanding of economics. We have to forget all this gender shit and just say, let people be whatever they want, just let them be. We have to do so many things in order to survive. But if we do survive then we will have got all of those things that needed fixing, fixed. So I’m sort of a…I don’t know what you call that?

An optimistic pessimist.

Yes. I’m 100 percent pessimistic and 100 percent optimistic. It’s either all or nothing. Really, it’s all or nothing.

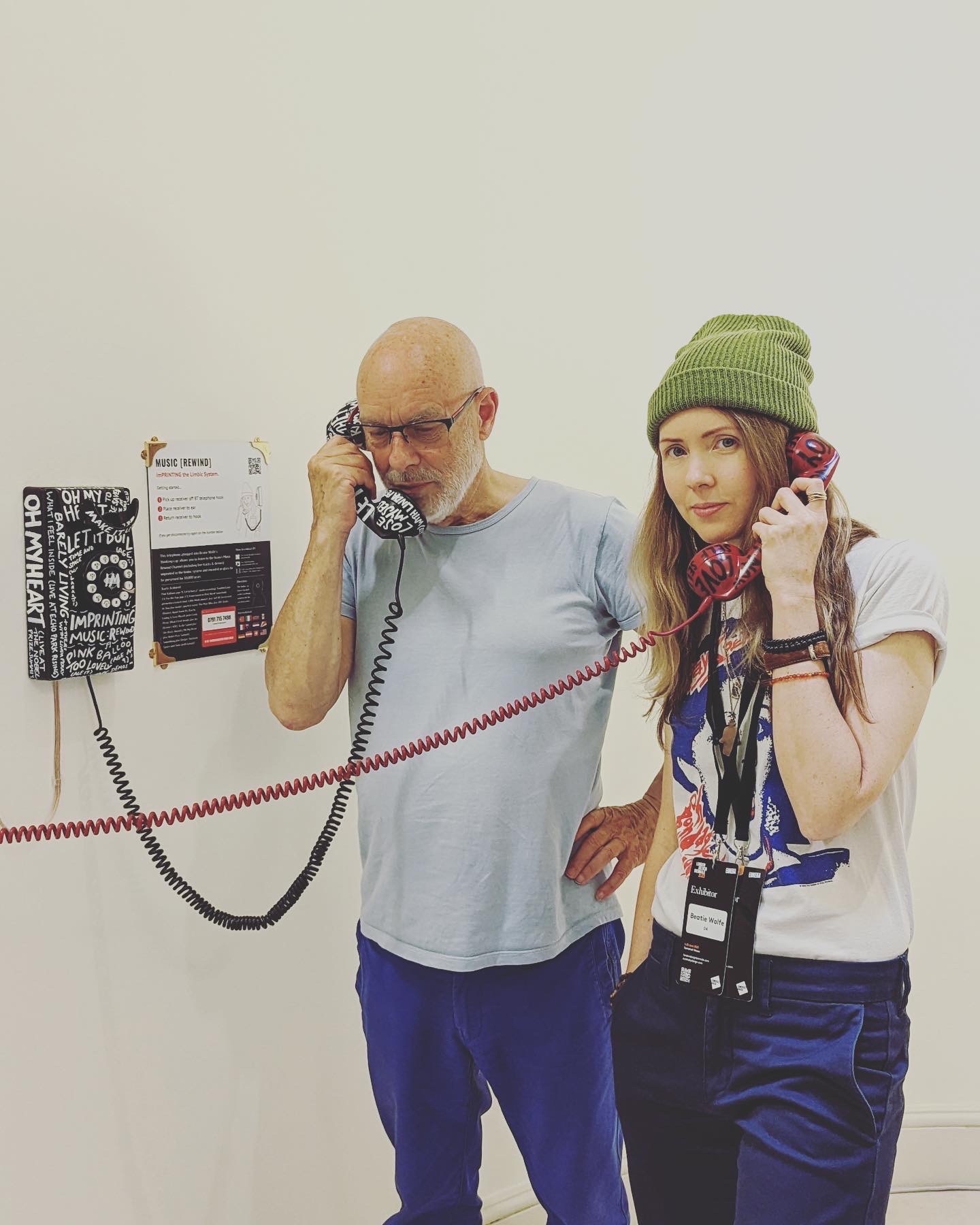

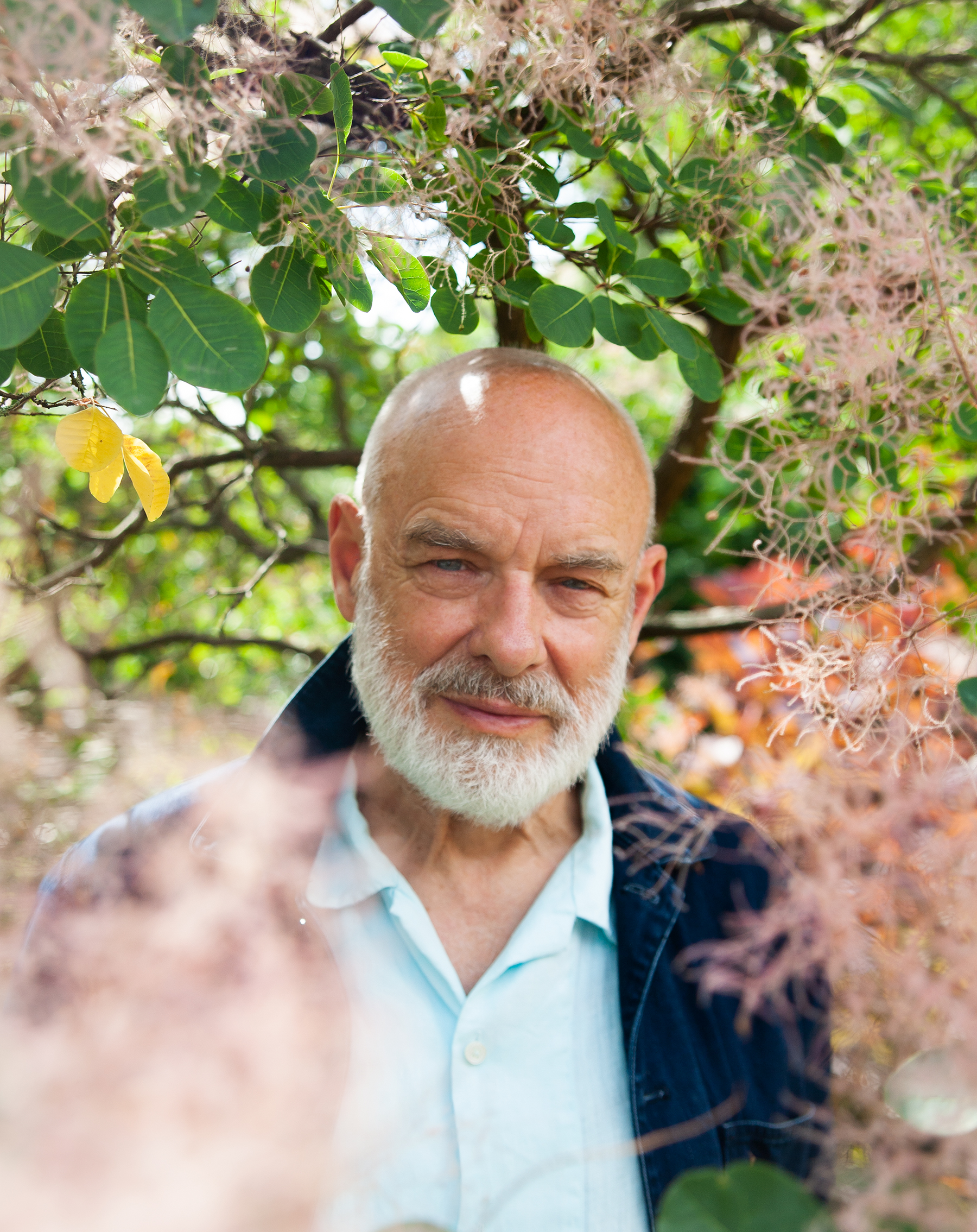

Brian Eno and Beatie Wolfe are both contributors to EarthPercent, a nonprofit organization supporting climate action in the music industry. Their conversation is the first in a series featuring EarthPercent artists. You can hear their conversation live on dublab radio, Orange Juice for the Ears with Beatie Wolfe.