- Interview by Tina Essmaker March 10, 2015

- Photo by Cameron Russell

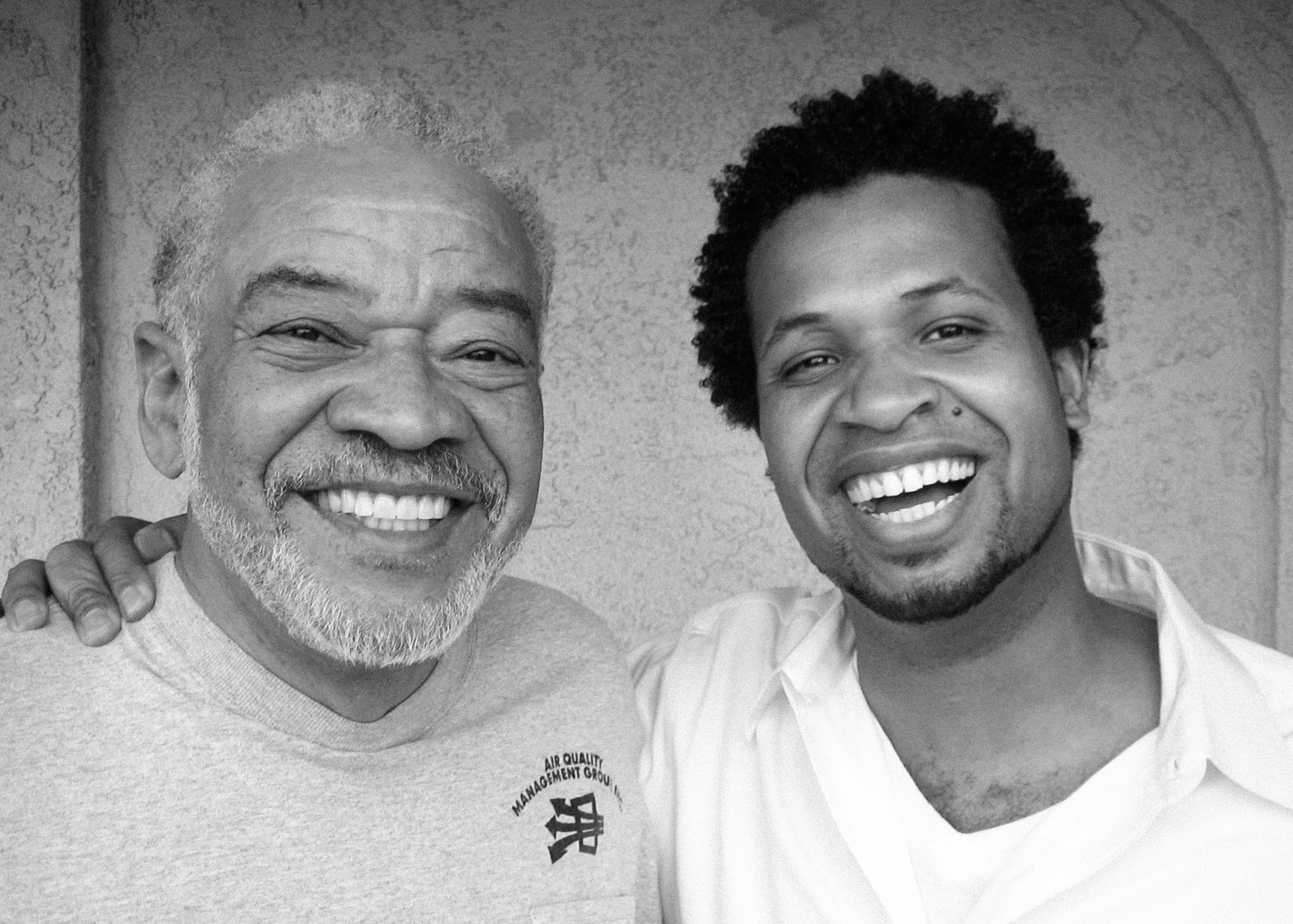

Damani Baker

A native of the San Francisco Bay Area, Damani Baker is a New York-based director and filmmaker. His first feature documentary about the life and music of Bill Withers, Still Bill, opened theatrically in 2009, and in 2010, he shot Music for Andrew Zuckerman. Damani’s career spans documentaries, music videos, museum installations, and advertisements, and he has worked for clients including Puma, Wired, IBM, and BMW, among others. In addition to his work, Damani is a professor in the filmmaking, screenwriting, and media arts program at Sarah Lawrence. He is currently in post-production on his forthcoming documentary, The House on Coco Road.

- director

- filmmaker

You’ve been working in film for a number of years. Did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew that directing and filmmaking was what you wanted to do? When I was in 10th grade, my dad bought me a used VHS camcorder for Christmas. When I finally figured out how to record audio over video without deleting the image by using two VHS decks, I became obsessed with making music videos. The first music video I made was with a family friend who did an interpretive dance to the 1991 hip-hop song “Follow Me Not” by the Dream Warriors. I loved that song. My favorite lyrics were, “Who is more fool, the fool or the fool who follows the fool?” The video I made went viral—not on the Internet, but everyone wanted a copy.

I felt like I made something people wanted to see, even if it was just a silly homemade music video. The ability to instantly capture something and then share it, and the possibility of making others happy, really fueled my obsession. As a 15-year-old, I had never experienced anything else like that. Before that, films had felt inaccessible; they were things made by others that I only watched.

We’re big fans of your feature documentary, Still Bill, about the life and music of Bill Withers. How did that project come about? A dear friend from high school, Alex Vlack, and I grew up being huge fans of Bill Withers’ music. My dad had Bill’s Live at Carnegie Hall album on heavy rotation at our house, and Alex was in a Bill Withers cover band during college. Alex and I talked about making a film on Bill as early as 2002. For years, we dreamed about making this film and we eventually got in contact with Bill’s wife, Marsha Withers. We pitched the film idea to her and she said that although Bill probably wouldn’t be interested, she would pass the idea on to him.

A year later, after approaching anyone and everyone we knew who might support the project, we spoke with Rachel Chanoff at Celebrate Brooklyn! She agreed to produce a Bill Withers tribute concert as part of their free summer concert series in Prospect Park, where they expected an audience of 8,000 people. At that time, Bill still hadn’t agreed to be in our film, but we now had a concert happening in his honor. Alex and I approached Martha with the idea again, hoping that the concert might get them to reconsider the film, or at least get us an interview with Bill. And that’s how we first met Bill. Three years and three hundred hours later, Still Bill was born.

Was there anything in particular that you took away from working on that project? Patience. (laughing)

You teach film at Sarah Lawrence, so you likely get asked for advice from your students frequently. What is your best advice to someone starting out in filmmaking, or any creative discipline? Being a director is about balancing confidence and humility. In order to be an artist, I think you have to be incredibly confident in your ideas, but also be willing to be vulnerable and misunderstood. I think this is especially true in documentary filmmaking, because you need to have the ability to sit across from someone and leave all of your own expectations at the door. It’s about creating a space where your subject feels safe and respected, and that’s when you figure out what he or she has to say that needs to be heard and shared with others.

You’re currently in post-production on The House on Coco Road, which is a very personal project. Tell us more about the premise of the film. I grew up in Oakland, California, surrounded by powerful women activists. My mom had served free breakfast with the Black Panthers in Los Angeles and then moved to Oakland where she was Angela Davis’ teaching assistant at UCLA—and later worked with the Committee to Free Angela Davis.

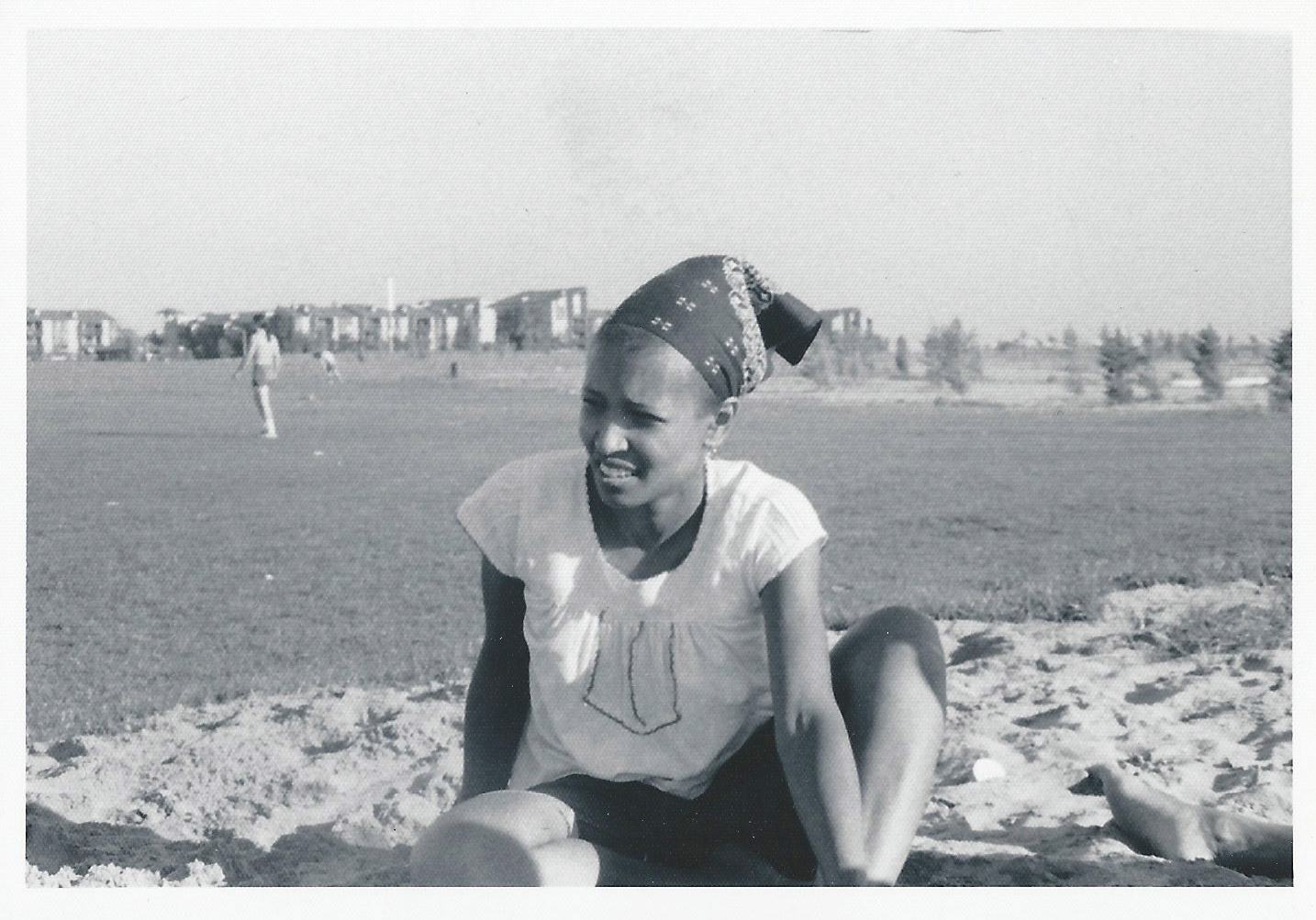

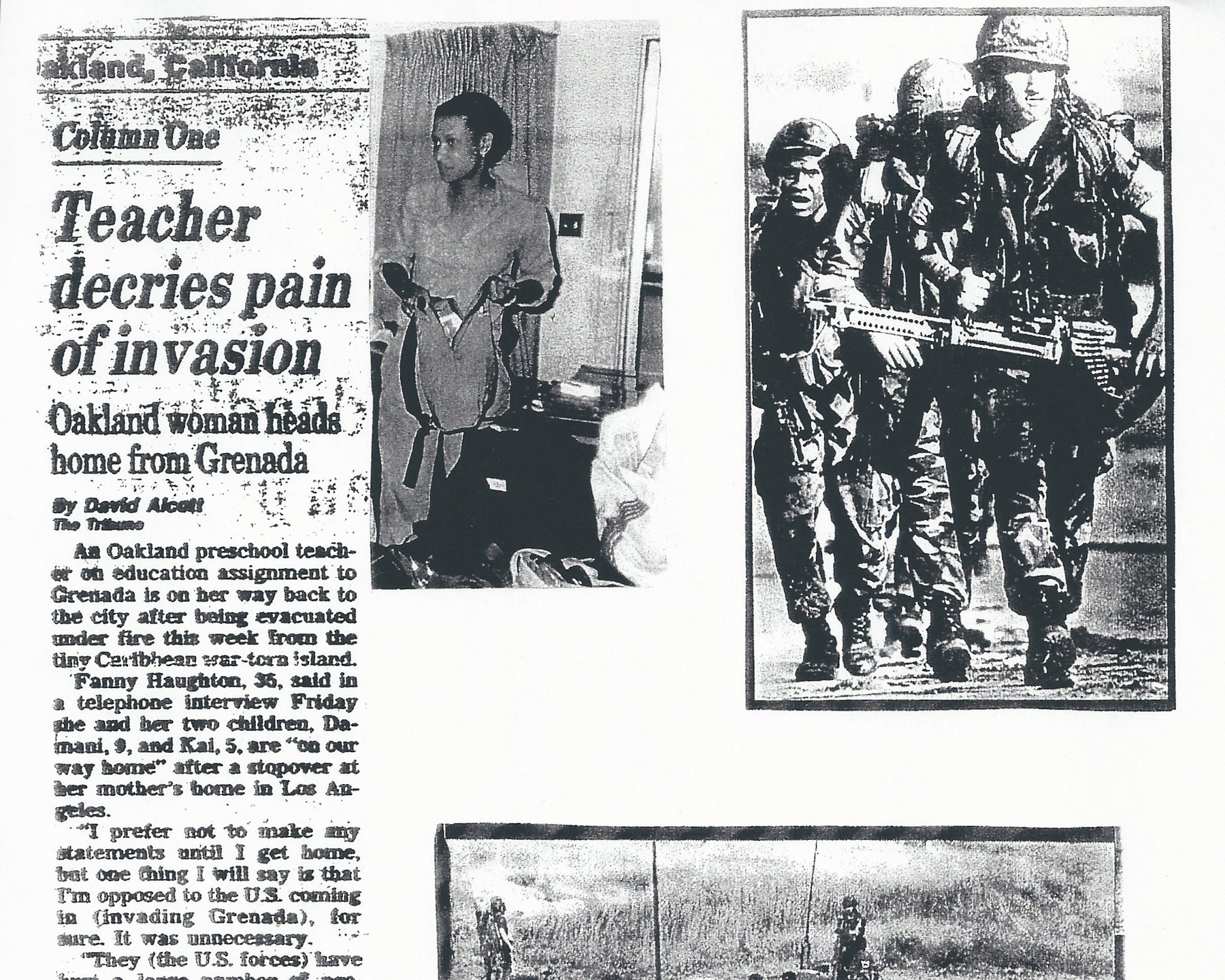

In 1982, my mother and the Davis family visited Grenada and were fascinated by what they saw. In 1979, the Grenadian people had carried out the first successful revolution in the English-speaking Caribbean and Maurice Bishop became the prime minister. The Revolution attracted workers from around the world, including my mother, who was offered a position in the Ministry of Education. In 1983, my mom moved our family—her, my younger sister, and me—to Grenada to join the Revolution. It was a powerful example of positive social change, and it was the kind of change my mom had dreamed of and worked toward for decades in California. Grenada was her utopia. I had never seen her happier.

We only lived there for a short period. Later that year, the prime minister was assassinated in a coup and the United States led a military invasion onto the tiny island. My sister and I hid under a bed as bombs shook our new home and changed its course forever. Three days later, we were evacuated; we were loaded onto a military cargo plane and taken back to the US.

In 1999, sixteen years later, I returned to Grenada with my mother. We began shooting a documentary film, seeking out her story, which not only felt untold, but also unfinished. This movie is about my mother and Grenada, but it’s about more than that. In a culture obsessed with fame and heroes, this film celebrates those who often go unnoticed. More broadly, it’s about intergenerational struggle, progress, love, and tireless sacrifices made by women I know to create a better future. My mother and a group of women had put their lives on the line and dared to build a better country, a stronger home. You may not know their names, but they have changed the world.

“In 1983, my mom moved our family…to Grenada to join the Revolution. It was a powerful example of positive social change, and it was the kind of change my mom had dreamed of and worked toward for decades in California. Grenada was her utopia.”

You’re currently in the middle of a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for the film. Why Kickstarter? Do you want the truth?

Yes, I want the truth. (both laughing) I know you started this project a long time ago, right? Right. This film was born before social media and the hard part about fundraising for the first round was that I only had the grant world for support as an independent filmmaker. That world was wonderful, and through grants I was able to take the project to where it is now. But the downside of that world is that it doesn’t give you a chance to build community around an idea. I went with Kickstarter because I not only wanted to invite people to support the film, but I also wanted to build an audience and community around it. It’s been amazing to receive feedback from people who are curious and genuinely interested in different pieces of the story that I’m telling.

You originally received some support from Sundance, correct? Yes, the first round of funding came from Sundance as well as the Paul Robeson Fund, Funding Exchange, and the Pacific Pioneer Fund, which were really awesome supports for me as an independent filmmaker. That whole process included filling out really long applications and being reviewed by a small committee of fifteen to twenty people—right now, I feel like I’m being reviewed by an audience of thousands, which is humbling. But it’s the same audience I want to share the film with and I get instant feedback instead of sending out an application and waiting two months to hear back.

Why did it take you so long to come back to this project? The other truth about this project is this. I started it right out of grad school and raised close to $100k in the first round. That afforded a really awesome research team and a full production schedule, which included a month in Grenada with a full crew. There was a little money left when we came back and we used that to do some preliminary post stuff, like organizing the footage and material.

Then my dad got sick with cancer and it became impossible to do something so intense and personal with someone I was very, very close to passing away. I stopped working on this film because I couldn’t manage it and what was happening in my own life. It was also early in my career and I needed to work. I started building a roster of clients in the nonprofit and commercial world and began making a living as a filmmaker. Then Still Bill came up, which took three to four years to complete—by then, ten years had passed.

When it’s finally finished and audiences watch it, what do you hope they’ll take away from The House on Coco Road? I think audiences will watch this film and see how the women in my life have built a better world, not through getting elected president or making a million dollars or writing a famous book or inventing a new technology, but through a dedication to family, compassion, and love.

“[The House on Coco Road] is about my mother and Grenada, but it’s about more than that. In a culture obsessed with fame and heroes, this film celebrates those who often go unnoticed…it’s about intergenerational struggle, progress, love, and tireless sacrifices made by women I know to create a better future.”