- Interview by Tina Essmaker October 21, 2014

- Photo by Samantha Stocks

Elliot Jay Stocks

- designer

- developer

- publisher

Elliot Jay Stocks is a UK-based designer, speaker, and author. He is the creative director of Adobe Typekit, cofounder of the lifestyle magazine, Lagom, founder of the typography magazine, 8 Faces, and an occasional electronic musician.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

The visual arts were always important to me, and they have taken up a lot of my time ever since I was a kid. Like a lot of kids, I drew for fun, but then people began asking me to make things for them. For instance, my school asked me to make pamphlets for theater productions and draw illustrated covers for parents’ night brochures. My early work was cartoony and super crappy, (laughing) but much of what I did—hand lettering, for example—was rooted in design.

It wasn’t until the end of high school that I began to shift my focus towards digital design. I was something of a technophobe and a late bloomer in terms of getting a computer, which is funny considering how everything has turned out. I used to draw an X-Men-style comic book that I reproduced at the house of a friend who was a penciler for Marvel Comics. He used a photocopier to copy his work before he sent it to the US for inking, and he let me come over to use the copier. I made loads of copies of my comic book, bound them up, and sold them to the other kids at school.

In the last year of high school, for our qualification in art, students could do whatever project they wanted. The project I focused on was a version of my comic book. I used a baby version of Photoshop—whatever the equivalent of Photoshop Elements was in 1997—to color it. That’s when I realized how amazing computers could be. It was a bit of a revelation, and I began doing design for our school magazine using super dodgy filters and putting crazy spirals everywhere—but you’ve got to get that out of your system, haven’t you? (laughing)

I took a gap year between leaving high school and attending university. During that time, I worked for a Virgin Megastore. A few of my coworkers and I were in bands, and we spoke to our managers and convinced them to release a CD of our music to sell in the store. We formed an ad-hoc record label; I did some of the recording for it as well as the CD packaging, point-of-sale artwork, and website. I built the website with the WYSIWYG editor on Homestead, and that was my first foray into “web design.” (laughing)

I enjoyed making that website, so I wanted to know how to do it properly. When I went to university, I learned a lot of Flash and made sites for friends’ bands. By the time I left university, I had a portfolio of extra-curricular work that happened to be rather music-focused, simply because that’s where my interest was. When I graduated, I was hired as a junior web designer at EMI Records, which was an absolute dream job because I loved music and web design. Suddenly, I had the opportunity to design websites for famous bands, which was awesome.

Especially straight out of college.

Yeah! I was happy and really fortunate. The sites were terrible, of course—they were bad Flash sites with auto-playing music, pixel fonts, and all of that fun stuff we had in 2004. (laughing)

But that was what everyone wanted.

I count that first job in 2004 as the start of my professional design career. I worked my way up at EMI as an in-house designer, but eventually left to work for a smaller, now-defunct record label called Sanctuary Records. Around that time, I had begun to veer away from Flash and move towards web standards—this was during the golden age of CSS Zen Garden and all that. When I moved to that new job, the company was really quiet because they were in the process of going down the pan. As a result, I had loads of time at work to learn and practice new coding techniques. I had never had that opportunity at EMI because the work was so unrelenting.

It was around that time, in 2006, when I released the first proper version of my website, and I was fortunate in that it made the rounds on the CSS galleries online. Everything started from there. On the back of that, I began writing articles for publications like Computer Arts and .net Magazine. Shortly after, I began speaking at a few small gigs upstairs at pubs, just to get my hand in. When I left Sanctuary, I joined Ryan Carson’s first company, Carsonified, and did a bunch of work for them as an in-house designer for a few months.

After a while, I decided to go freelance, and I became independent in May 2008. That was a cool period because I had been doing freelance work for years in the evenings and weekends and it had gotten to the point where I had to either go with the day job or the freelance work, and I chose freelance. My then-girlfriend, Samantha—who’s now my wife—was traveling through Asia, so I decided to go stay with a friend in Norway for a couple of months. It was a big upheaval to leave London and leave my job all at once.

I continued freelancing for several years, until about a year and a half ago when I joined Typekit as Creative Director. That was the first break I took from the independent life, as it were. That said, there are a lot of projects I’ve done on the side while at Typekit. I work remotely, so I am able to balance a feeling of independence while still working a full-time job.

How did your side projects come about?

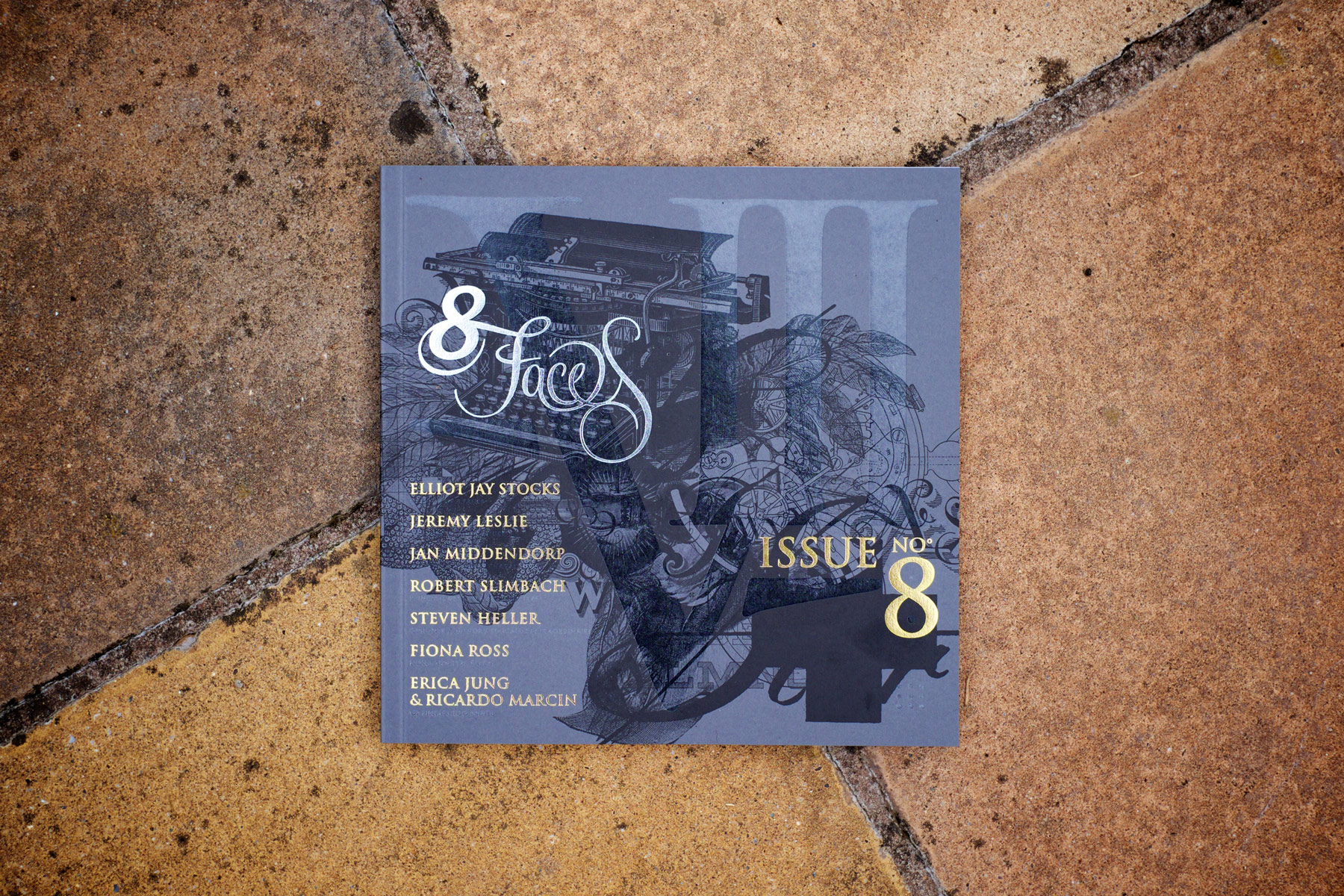

The main side project I did for four years was 8 Faces magazine, which has now come to an end: we put out our eighth and final issue a few months ago. That was running before I was at Typekit, which was interesting because a few people from Typekit said that was what made them call me: it wasn’t necessarily my web work, but my personal work on 8 Faces. I considered that magazine a semi-throwaway side project, but it ended up spawning a bunch of other opportunities, including my current role at Typekit. Aside from 8 Faces, I had a company with Keir Whitaker called Viewport Industries for about three years; we closed the company in September.

By far, the biggest project I have going on right now is the lifestyle magazine Lagom, run by myself and my wife. We literally just released it this month. That’s my only side project apart from the occasional noodling with music-making, but that’s on a much lower rung of priorities. (laughing)

Congrats on the magazine!

Thank you! Cheers! I’ll be sure to send one over.

For those who don’t know, what is Lagom about?

Lagom is a lifestyle magazine, which is a huge umbrella term, but, specifically, it’s a lifestyle magazine that celebrates innovation and creativity. It’s about people who make a living from their passions or pastime activities, people who offer inspiration to readers. The actual word lagom has no direct English translation, but it’s a Swedish word that is loosely about not having too much or too little of something: just the right level of balance. The theme of balance is something that runs through the magazine in the form of people who have a balance between their work lives and their personal lives, and people turning their passions into something they can make money from. Like 8 Faces, it’s designed to be an object with high production value that people want to keep on their shelves rather than throw away. The phrase I use is, “If you do something with dead trees, you should do something special.” So we use nice, uncoated paper and a foil-blocked cover.

From a purely print design aesthetic, every time I did an issue of 8 Faces, I learned more about good typesetting. That is something that continues to be interesting to me about jumping between print and the web: every time you go back to design something for the web after you’ve designed for print, your eyes have been opened to all these new possibilities. On the web right now, there is so much we can do in terms of typographic control. If you’re frustrated with your website looking different in all kinds of browsers and scenarios, then it’s kind of nice to go back to the fixed form of the printed page; and then when you realize you’ve printed 4,000 typos, it makes you appreciate the web. (laughing) I love juggling the two mediums because, not only is one the antidote to the other, but they also inform each other.

It’s been a fun journey for us having published online for so long and now having a print counterpart. It gives you an opportunity to think about your content differently, and it’s cool to have something tangible.

Yes, exactly. You’ve also done some great experiments with one influencing the other: the fact that your new site is so influenced by the print version is really cool.

Yes, thanks! So, where did you grow up, and was creativity a part of your childhood?

I grew up in the suburbs of London. My parents were incredibly encouraging about creativity and celebrating the work I did. My dad was a graphic designer as well, so he taught me a lot of principles from a young age. He also used to bring home fantastic professional drawing utensils like marker pens and propelling pencils with different lead weights. It was great for me, especially when I became more serious about illustration in high school. Even though I spent more time indoors drawing endless iterations of Ninja Turtles instead of playing outside with my friends, it all informed the work I did later.

Was there an “Aha!” moment when you knew that this was what you wanted to do?

There was definitely an “Aha!” moment when I discovered that computers could be useful. At that time, I had dismissed them as something that allowed you to cheat at art, but I realized that they allowed me to do something I wouldn’t have been able to do with another tool.

In terms of getting into web design professionally, there was a moment around 2001 when I started tinkering with Flash and becoming inspired by others’ sites. For instance, the Juxt Interactive site by Todd Perguson was very grungy and reminiscent of David Carson, which excited me about what could be done on the web. Another site that influenced me was My Pet Skeleton. There is also a London-based agency called Hi-Res! that did the site for the Donnie Darko film. It was rather influential at the time: a kind of crazy, Flash-based, art piece probably more at home in a gallery than as an online advertising tool. Although those are different from the kind of work I do now, those are the three sites I can remember that got me excited and made me want to go into web design. That was when I was a student just learning about the medium.

There was another “Aha!” moment that happened further along, when 8 Faces started in 2010. That magazine came about as a sort of semi-selfish reaction to the web because I was tired of my work disappearing after years, months, or maybe even weeks. I wanted to make something permanent, something to smell, put on the bookshelf, and show my friends and family. I had done some print before, but nothing as fully fleshed out as a magazine, and it turned out to be successful. That was the moment when I thought, “Wow, I really enjoy doing print work.” Then, when I went back to doing web work, my eyes had been opened to doing decent typesetting for print, which then informed my digital projects. That moment made me realize that the web is not 100% where my interest lies. I’m interested in a balance between web and print; that keeps me happy and sane.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

I haven’t necessarily had any mentors. There certainly have been prominent people in the web community who I looked up to and who I met at conferences and eventually become friends with over the years. But there wasn’t any specific person who I had a one-on-one relationship with.

As for my skills, I’m pretty much self-taught. I’ve never gone through an official design course. I did design and art for my high school qualifications, so I had consistently steered myself in that direction, but my degree wasn’t in design. I mostly learned on the job, some of which was from the sheer volume of sites I made when I was at places like EMI. You gradually learn and get better because you’re doing so much so quickly. By and large, I’ve had to learn that way with print as well.

There is a lot to be said for learning on the job, but there were times when it would have been nice to have done a course that taught me core lessons in graphic design; instead I had to learn through experience. There are a lot of typesetting principles that would have been nice to know from the get-go so I wouldn’t have to look back at some earlier issues of 8 Faces and think, “Oh my, what was I doing?” (laughing) But we all have those moments looking back at older work.

Have you taken any big risks to move forward?

I suppose it was a big risk to go freelance. I had a series of steady jobs while freelancing on the side, but making that leap into the unknown was risky. At the time, I gave up my flat in London, my girlfriend was traveling, and I moved to Norway for a summer; a lot changed.

I also didn’t have much money saved up. Someone had told me, “If you have a couple grand in the bank, you’ll be fine!” That money depleted quickly. It felt like a huge risk at the time—other people certainly talked about it in those terms—but after having done it, I found that it wasn’t so bad. As soon as people knew that I was independent, it wasn’t hard to get work. People always need design.

There were other big risks as well. The first was starting 8 Faces as a print magazine because it was such a radical departure from what I had done previously, and because I had to spend money to produce it. The magazine we just launched, Lagom, is, in a way, less of a risk because we know more about what we’re doing, but we still sunk a big chunk of money into printing: we printed twice as many copies than any other issue of any magazine or publication we’ve done previously. That was a much more tangible, financial risk.

I have a strong belief that the industry has easily built up how much of a risk these endeavors can be. Maybe they’re not such huge risks? I’m a firm believer in taking risks, but I like to downplay them a bit as well. When younger designers ask me about going freelance, there is this perception about the risk; there’s the very real financial risk, but also the risk of going out on your own and being the person who has to deal with everything, from clients to design, and maybe development as well. That turns a lot of people off: a lot of young designers get too scared by this perceived risk. I would like to think of myself as someone who takes risks and encourages others to do so, but also someone who tries to be responsible in telling people that risks are worth taking.

Are your friends and family supportive of what you do?

Very much so. Obviously, there are family members who don’t get what I do, (laughing) but they are supportive. Sometimes support comes from places you wouldn’t expect: people who aren’t close friends nor web or design people suddenly started tweeting and posting on Facebook about the release of Lagom. They got it and they care about it, and that’s amazing.

You mentioned that your wife, Samantha, is doing the magazine with you. Does she work in a similar field, or did you decide that you wanted to work on a project together?

My wife is a writer, and she went freelance about a year and a half ago. We run our company together, but she had her own writing clients apart from my clients. We wanted to do a project together for a long time, so she initially started helping me out with Digest. When Keir and I decided to fold that publication, Sam and I decided to do our own new magazine. She is the editorial director of the magazine; she influenced how we divide up the sections, the kind of content, and the kind of people we approached; I’ve lead more of the creative, visual side.

This is the first time Sam and I have worked on a proper project together, and it has been fantastic. There have been no arguments, (laughing) and any differences have been sorted out with discussions. She actually had way better ideas than I did, and the magazine has ended up being better because of the two of us doing it together. Of course, as you know, it’s not just about the magazine. It’s also about the behind-the-scenes stuff: the distribution, partnerships, promotion, social media, and all of the things that are semi-invisible. At least, a lot of the effort that those require is semi-invisible. Working with her on that has been absolutely brilliant. We’re so pleased with the final product and, as a result, we strongly believe in the husband-and-wife team. (laughing)

We do, too! So, do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

Definitely. I’ve worked on projects for myself and ones that have been for a larger team, which is certainly the case with Typekit.

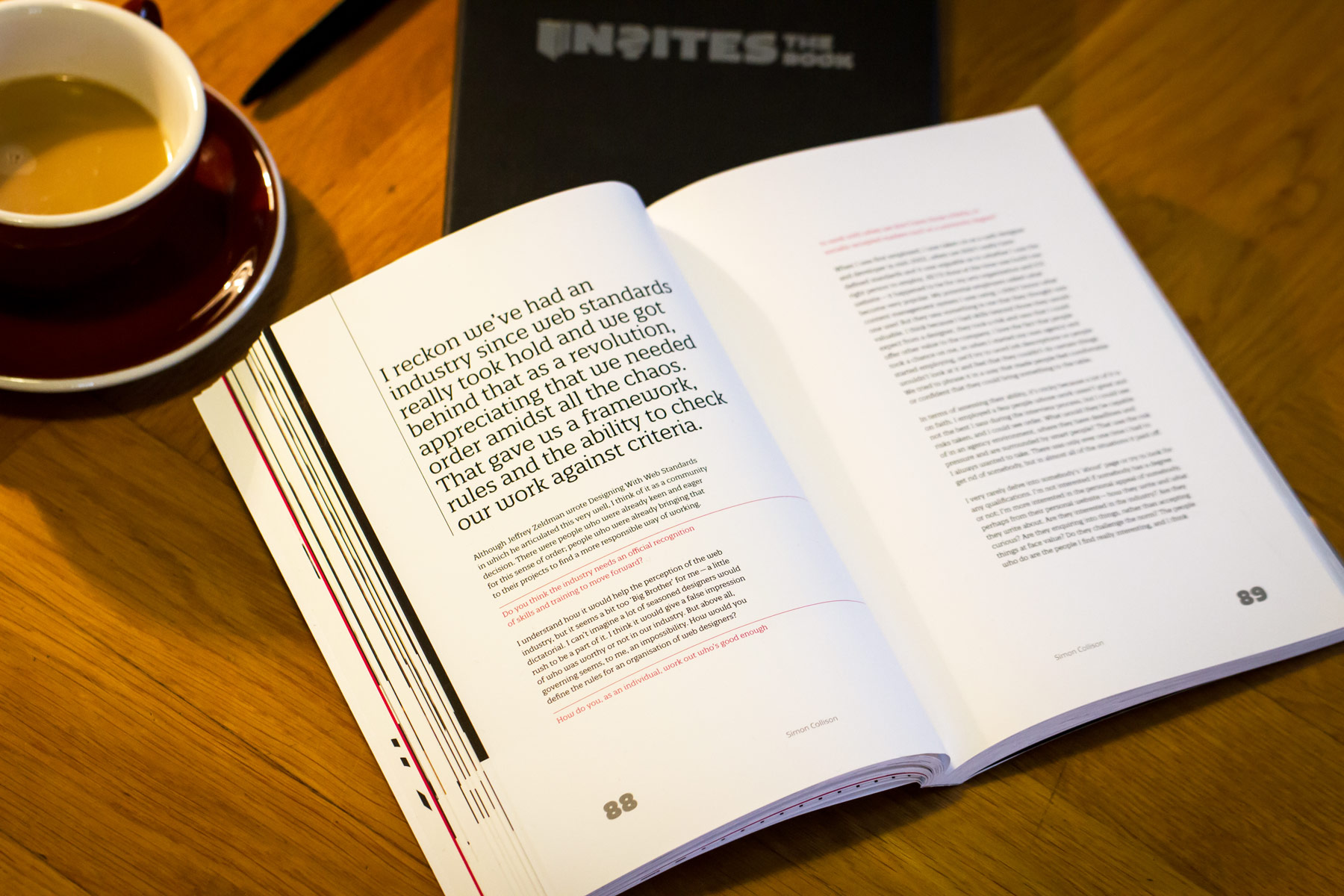

A couple years ago, Keir and I put out a book called Insites: The Book, which included interviews with web folks: developers, designers, engineers, entrepreneurs. I was quite proud of that, not necessarily because of the actual artifact, but because so many people said, “It was interesting to find out about so-and-so’s humble beginnings.” Many of the people we interviewed sort of fell into jobs without knowing what they were doing, and then they tried something, and then they became big web superstars. (laughing) With the size of the web community now, it’s easy to put people on a pedestal. It’s nice for people to see that everyone has humble beginnings.

When we collected the stories for Insites, we realized that lots of people are making it up as they go along. If you do decent work, keep at it, and you’re nice to people, then it’s possible to gradually make a name for yourself in the industry. It’s important to keep telling stories about how people start out. Sometimes it’s more a matter of luck than of producing amazing work out of the hat. That doesn’t happen; it’s a myth.

Are you creatively satisfied?

Right now, it’s a real balance. We just released the magazine, and that post-release high of seeing your work out in the wild is a great feeling. We’ve had lovely feedback on it, and it’s a pleasure to see all the Instagram posts of it arriving on people’s doorsteps and in shops. Of all the artifacts that I’ve produced over the years, physical or digital, this is the one I feel really satisfied about. Of course, I’ll change my mind in a couple months.

I’m creatively satisfied with something I’ve just created, however, I’m not creatively satisfied in general. I want to do so much; I feel bothered when I’m not creating something. I have side projects that I can do outside of my day job, and I make music so that I can do something outside of design. I jump between different mediums because I would go absolutely crazy if I was stuck inside the boundaries of one. Generally, I’d say that I’m not creatively satisfied. If I was, I probably wouldn’t be constantly thinking, “Man, I should be creating something!” I should probably chill out a little bit and learn to have more downtime than I actually do.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

The main piece of advice that has worked well for me—and this might not necessarily work for everyone—is to not conform too much to what is currently trendy. I don’t think my work is radically different or anything, but I’ve consistently tried to do things a little outside of the norm; that has served me well. From an aesthetic point of view, it has helped some of my work be recognized. That was certainly the case with doing a printed magazine in the digital age, when no one else was doing it—now everyone is doing a magazine. At the time, it was a huge risk.

In general, it comes down to not worrying too much about what others think. Ultimately, you’re going to upset some people, but if you’re true to yourself and create something for the right reasons—as in, you genuinely love what you’re doing—then you will succeed. If no one sees what you’ve created or buys your product, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a failure. If you’ve made something to make yourself happy, then that’s success.

Where do you live and how does it influence your creativity?

I left London about five years ago and now live just outside of Bristol. I absolutely love it; it’s the first place in my entire life where I’ve truly felt at home. It’s a wonderful creative city in every sense of the word; there’s a lot of art, it has a rich musical history, it’s beautiful from an architectural and nature point of view, and there are loads of independent people here. It has a DIY spirit of independence that I identify with.

Bristol is also lovely because although it’s a city, it’s extremely chilled-out. I come from London, so I’m used to the busyness, but these days I prefer a slightly quieter pace of life. I probably wouldn’t want to only be in the city, and I wouldn’t want to just be in the countryside, either. That balance is important to me and has a strong influence on what I do. That sense of balance is also what Lagom is about: our own sense of why we like this area comes across in the magazine. We’ve actually been quite influenced by our geographical repositioning of late.

Is it important to you to be a part of a creative community of people? And, if so, do you find that more so where you live or with an online community?

Yeah, it’s important to me. We have a collective here called Bristol Independent Publishers, also known as BIP. It’s made up of Lagom and a number of other indie magazines that have come out of Bristol recently, like Another Escape, Cereal, Boneshaker, Off Life, and Lionheart. Having that community of publishers is great. Although Lagom is pretty much an international magazine in its subject matter and contributor list, there are a bunch of people specifically from the Bristol area that we’ve used as writers, illustrators, designers, and photographers.

What does a typical day look like for you?

My typical day is a bit of a mix. Obviously, the majority of it is doing Typekit work. I tend to have a lot of meetings towards the end of my day when the East and West Coast wake up in the US. We have a daily stand-up meeting at 10am, which is 6pm for me, so I end my day when everyone else begins theirs. Unfortunately, in between meetings, there is also lots of email.

Every day I take my dog, Ozzy, out three times. During lunch, he and I go for a nice, long walk around the countryside, which is lovely. He’s three-quarters Black Lab and one-quarter Rhodesian Ridgeback; he basically looks like a very muscular Black Lab. (laughing) He forces my wife and I to step away from the computer, take a bit of a breather, and get some exercise.

That’s important to do. Alright, last question: What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

That’s a tough question, but it is something I start to think about more as I get older. I’d like to leave a legacy of having created work that people enjoyed, work that’s been done for the right reasons. I’d like to believe that some of the work I’ve done, and hopefully more of the work I will do, will have some effect on people, even if it’s small. Sometimes people come up to me and say, “I love this project you did years ago, and it helped me with a project I was stuck on,” or, “This changed my thinking about a particular subject.” People have said about some of the speaking I’ve done, “I didn’t see it from that point of view, and hearing you present another point of view has been really useful to me.” Little moments like that have meant a lot to me. A legacy comes down to doing good work, with good people, for the right reasons. By and large, that principle is what I try to live by.

“…it comes down to not worrying too much about what others think. Ultimately, you’re going to upset some people, but if you’re true to yourself and create something for the right reasons—as in, you genuinely love what you’re doing—then you will succeed.”