- Interview by Tina Essmaker & Bermon Painter November 18, 2014

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

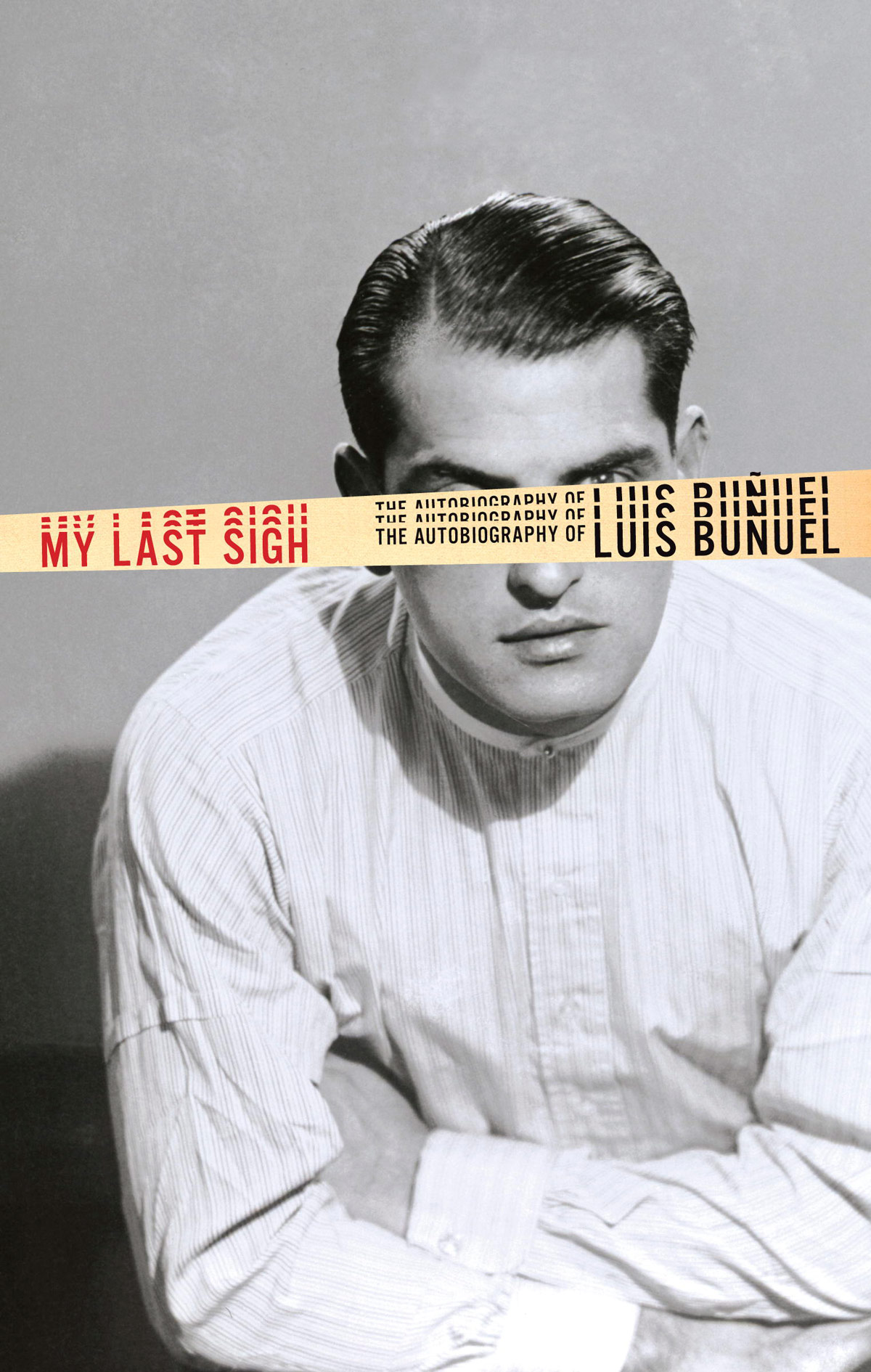

John Gall

- artist

- designer

- educator

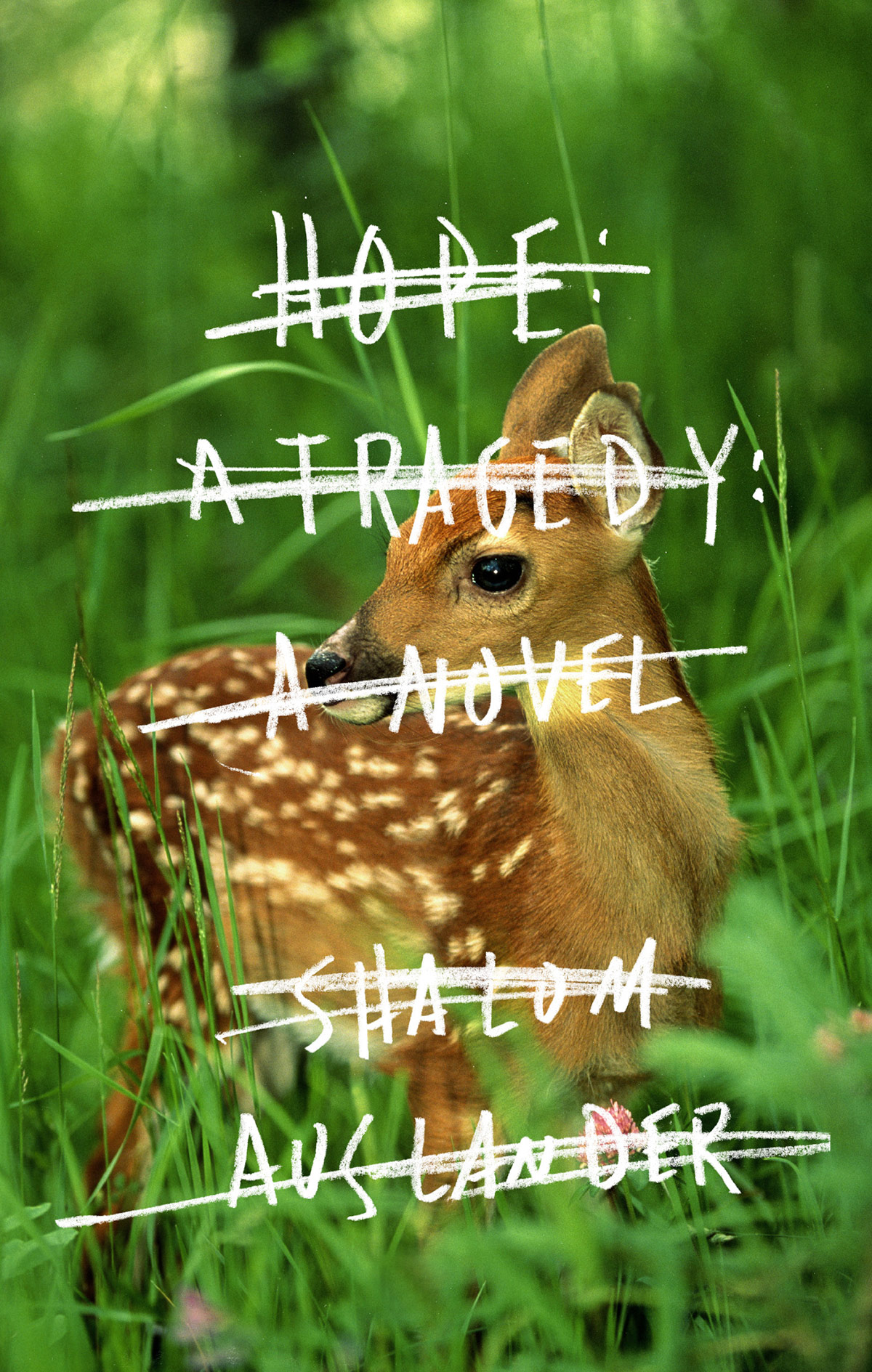

John Gall is a designer, artist, author, teacher, and creative director for Abrams Books. Previously, he was art director for Vintage and Anchor books where he designed covers for the likes of Haruki Murakami, McSweeney’s, Vladimir Nabokov, and hundreds of others. He has served on the board of AIGA/NY and teaches a course on book design at the School of Visual Arts.

Editor’s note: Guest interviewer, Bermon Painter—one of our generous Kickstarter campaign backers—joined Tina to interview John at Upright Brew House in Manhattan’s West Village, and as you’ll see, it was a great time. Thanks, Bermon!

Tina: Describe your path to becoming a designer.

I was born to blue-collar parents in suburban New Jersey. I remember my dad drawing a little and showing me how to do shading. My mother, who claims that she’s the least artistic person on earth, always did little craft projects. Once when I was a kid, I saw her knitting something and asked if I could try it. She said, “Okay, but you’ve got to put it away before your father gets home.” (laughing) I don’t remember what I was making, but it was fun to make something out of almost nothing.

I think about that every once in a while because I’m barely a generation removed from being a coal miner in Pennsylvania, where my dad is from. I’ve thought to myself: “I went from coal mines to Newark, New Jersey, so how am I in Laurie Anderson’s loft while she serves me soup and we talk about her new CD design? How did I end up critiquing student work at Yale for Michael Beirut’s class?”

I have read a few of your other interviews, and almost everybody starts with drawing as their first artistic pursuit. Those were some of the best times of my life: sitting on the floor all day making drawing after drawing. Then I’d hold one up in front of someone and they’d say “Hey, that’s nice!” That’s basically what I’m still doing, right? Holding up a book cover for someone to comment on. Except now people are more than happy to tell me, “Hey, I don’t like that so much.”

Bermon: Were your parents supportive of your artistic pursuits or did they want you to be more practical?

I don’t remember ever “coming out” to my parents as wanting to be an artist as it wasn’t really part of the equation. They were supportive of my creative pursuits, but I was just drawing hot rods and stuff. (laughing)

I pretty much knew I wasn’t going to be a fine artist. I thought, “What would I do? Where would I even start?” I had no frame of reference as to how or why I would make art professionally. I needed a place to apply it.

Tina: Was creativity part of your life from an early age?

Yes. I didn’t take many art classes growing up; there wasn’t a lot of that kind of support, you know, other than basic public school art classes. I was decent at math and liked drawing, so when I graduated from high school, I wanted to do something that was part creative and part analytical. I decided to become an architect, so I studied architecture for a semester. As part of the program, I had to take either a life drawing class or a mechanical drawing class. I needed the mechanical drawing class because I had no idea how to draw like that, but I was given the life drawing class instead. I ended up loving it, and I slowly drifted into the design program. I had a fantastic professor named Frank D’Astolfo, who showed me the way through the then small, concentrated program. I also absorbed everything I could get my hands on, like old Art Directors Club and AIGA annuals and Print Magazine, which I had to physically search out, unlike today.

I was one of four graphic designers in my graduating class. After I graduated, I started to look for work in New York. I had to compete with people from all of the other design schools, so my professor gave me the names of a bunch of people to call. There I was, sitting in my kitchen, calling Massimo Vignelli to ask if he could look at my portfolio.

No way.

Yeah! I went to places like M & Co. and Chermayeff & Geismer looking for work. I did a lot of portfolio drop-offs, a total thing of the past, to try and get a foot in the door.

My first paying job was painting two grocery store signs. It took me about two weeks to finish something that a real sign painter could do in a day. (laughing) My first design job was with a mass-market book publisher, which meant that everything I learned in design school was thrown out the window. I had to stretch type and do all of these horrible things that I wasn’t taught to do—things I’d love to do now!

I only worked for the book publisher for about a year, but I met some interesting people during that time. I met Steve Brower, who heads the MFA program at Marywood University. Through Steve, I met James Victore, who was doing some book cover work with Paul Bacon. Then James started a politically motivated poster design collective called “Post No Bills” that I was a part of for a year or two.

After I left publishing, thinking I didn’t ever want to do it again, I went to work for a brand consulting firm called Landor Associates for a while. Sorry, these weren’t very exciting years.

That’s kind of the point.

After working at Landor, I somehow fell back into publishing. I kind of already knew how to do it, but I wanted to see if there was a way to make it work for myself. I didn’t want to only use the methods other people wanted me to use.

I bounced around and freelanced for a while until a job opened at Grove Atlantic press. That was an interesting place for me because so many of the books I grew up reading that opened my eyes up to the world—books by William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, and authors like that—came through Grove press publications. In the 1950s and 1960s, Grove had a great designer named Roy Kuhlman, who not only designed many fantastic covers, but also totally defined the look of a generation. That’s what attracted me to that company, although it was completely different by the time I started working there.

What was your role there?

I was hired on as an art director. It was me and one other person, and the two of us pretty much did everything.

Meanwhile, I had been doing work for the guy who used to run Grove, Barney Rosset. Barney’s story is an amazing one, which I won’t go into here other than to say that he was a trailblazer and a brilliant, eccentric man. Under his ownership, Grove published radical avant-garde American and European literature, as well as a lot of Victorian erotica. (laughing) That’s kind of how he made his living later: repackaging that content over and over again under different titles. I somehow got a job working with Barney on those books. They weren’t great design projects, but I’d go up to his office for meetings, he’d have a rum and Coke, and he’d tell me tales of the older days of renegade publishing, like when someone tried to firebomb his offices.

But once I took the art director position at Grove, Barney didn’t want me to work for him because it was too much of a conflict of interest.

How long did you work full-time at Grove?

A couple of years or so. I can’t remember exactly how long I was there, but I had great projects and a good backlist that I worked on. A while later, I received a call from Carol Devine Carson at Knopf Doubleday about a job art directing Vintage Books. I ended up working there for 15 years. It was hard to leave. That job was fantastic, but I wanted to do something else—even though I wasn’t quite sure what that was. Should I go out on my own? Should I work for someone else? I had a family and all of those kinds of issues to consider.

In 2012, a creative director position at Abrams opened up, and that’s where I am now. It has filled in a lot of what was missing in the work I had done before. Instead of only doing covers, we design the whole book. I’m more deeply involved in every aspect of the publishing operation. I have an eye on things from acquisition through publication. It’s really fascinating.

Was there an “Aha!” moment when you realized that design was what you wanted to focus on?

I think my “Aha!” moment came when I started taking design classes in college. There was one day when the whole class was struggling with a project. The teacher came in and ripped everything off the wall and told us, “This is all terrible.” Then the teacher pointed to one of my sketches and asked, “Who did this?” Gulp. It was a typography composition, and I had done something interesting with positive and negative space; he liked it. From then on, it all started to click.

Did you have any mentors along the way?

For the most part, it was probably that college professor I mentioned, Frank D’Astolfo. I had him for all four years of design school, and he was a very supportive and inspiring figure in my life. After college, I had to start figuring it all out on my own.

It’s interesting that you started out with connections to designers like Massimo Vignelli, but still didn’t get hired. But you kept trying, and the universe guided you along your path.

Those were not connections at all. They were phone numbers. But that’s true: Massimo didn’t hire me. I also remember interviewing at a design firm called Double Space. They were fantastic and gracious enough to bring me in to talk with them. I came in with my little jacket and tie on, and it was like walking into a kindergarten class. Designers were running around, throwing things at each other, and having a great time. (laughing) I thought, “Oh, I get it. Or maybe I don’t!”

Sometimes you are just not ready for what you think you are. You are on a path, even though it might not be the one you had planned.

Bermon: I’m wondering—if you took your early years and fast-forward to being a teenager in the digital age, how much would that impact how you work? I sketched a lot growing up when everything was very analog. Now I have a 17-year-old daughter who sketches a lot, too. She still uses a sketchbook, but a lot of the work she does now is on the computer with a Wacom tablet.

I’m sure I would be all about using digital technology. I see my own kids doing that. They used to draw a lot when they were younger. Most kids leave drawing behind once they become more conscious of what they’re doing because they start to think that their drawings need to look a certain way, which is kind of sad.

My kids gravitate towards creative ways to use computers. One of my sons spends hours, even days, making computer animations. He wouldn’t be doing that if it was done in the traditional way. With a computer, there is an immediate response, and you quickly feel a sense of accomplishment. I don’t think that’s good or bad—it just facilitates the creative process in a different way.

Tina: Have you taken any big risks to move forward?

I don’t think I’m a big life risk-taker. I like to believe, and hope, that I channel that risk-taking energy into the work. I want to be open to taking chances and doing something wrong, or whatever is necessary to get at a new way of looking at things.

Taking the Abrams job was kind of a big risk for me because I had been in a fairly comfortable position at Knopf Doubleday for 15 years. People stay there forever: at our annual Christmas parties, awards were given out for 35—and sometimes 50—years of service.

That says a lot about a company, though.

Absolutely. It was hard to leave, but I knew I had to take the job with Abrams. I wanted to work with more visual material in book form. I love literature, but I love art and design even more. Now I can play with that stuff every day.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Sure. They’re not not supportive: I pay for their food and stuff. (laughing) Seriously, they are super supportive. My wife was in interior design and now teaches art, so she knows the drill. My kids have seen me working on different things over the years and have said, “Oh, that’s what you do? That’s so cool!”

How old are they?

I have a 16-year-old and a 20-year-old.

Oh, so they’re older.

Yeah. Do you have kids?

Nope.

[to Bermon] How many kids do you have?

Bermon: Just one for me.

My son is studying industrial design, and he’ll text me stuff he thinks is cool. My wife and I spent the first part of our kids’ lives dragging them to art museums, and now we’re seeing them realize that maybe it was relevant. For one of his school projects, my son designed a line of shoes based on Penguin book covers. I saw them and thought, “Ah, yes! It’s all coming back around.”

Tina: That’s awesome! Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself?

I find it hard to think about design in terms of changing the world, but it’s important to think about design in terms of the decisions you make about what you make. Ask yourself: “What am I putting out into the world? Am I helping sell Big Macs or deodorant or iPhones or whatever?” I have nothing against any of those, but at some point in my life, I decided to focus on books. Books are intrinsically good: even the worst book—with some notable exceptions—isn’t truly bad. If people are reading, it is good. As designers, we’re attached to the selling of something; no matter what we’re making there is a selling component. In that sense, the decision to work with books was very much about the larger picture of what I was helping to usher into the world.

I also teach a book cover design class at the School of Visual Arts here in New York. I’ve been teaching for about seven years, and I enjoy it. Teaching forces you to articulate what you’ve been intuitively doing all this time.

Are you creatively satisfied?

I can be momentarily creatively satisfied. I think that’s why we keep doing this: you finish something and think it’s great, but then you start looking for what’s next. It’s ongoing. I don’t approach creativity as being a search for satisfaction because it’s a continuing exploration. Or maybe I’m just a malcontent who will never be satisfied. (laughing)

“I find it hard to think about design in terms of changing the world, but it’s important to think about design in terms of the decisions you make about what you make.”

Is there anything you’re interested in doing in the next 5 to 10 years that you’re not doing now?

I’m interested in exploring the editorial side of publishing—and we’ll see how it goes, because there isn’t anything on the table yet. I’ve been talking about different book projects. I’m a big fan of graphic design, so if I can work with someone, hang out, look through an archive, and make a book of their work, then that’s great. It’s not a great leap from art directing: you’re working with someone else to create something new. That’s something I’m interested in doing more of.

I’m definitely one of those side-project people. I’m doing a lot of illustration work at the moment, and I’ve been doing collage work as well. I have a couple other projects still under wraps, but I hope to reveal them soon.

I saw some of your collages online. I really enjoy them.

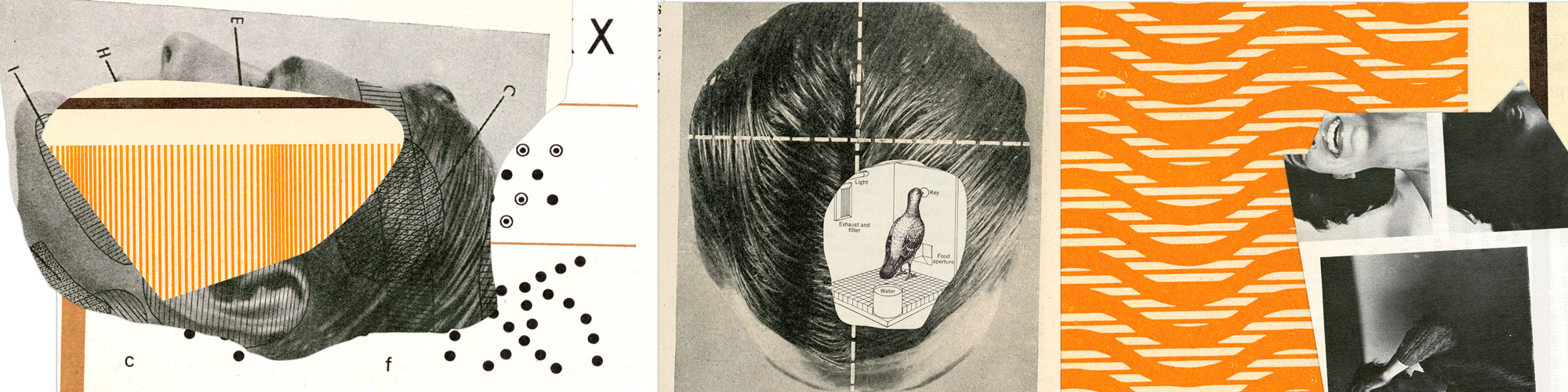

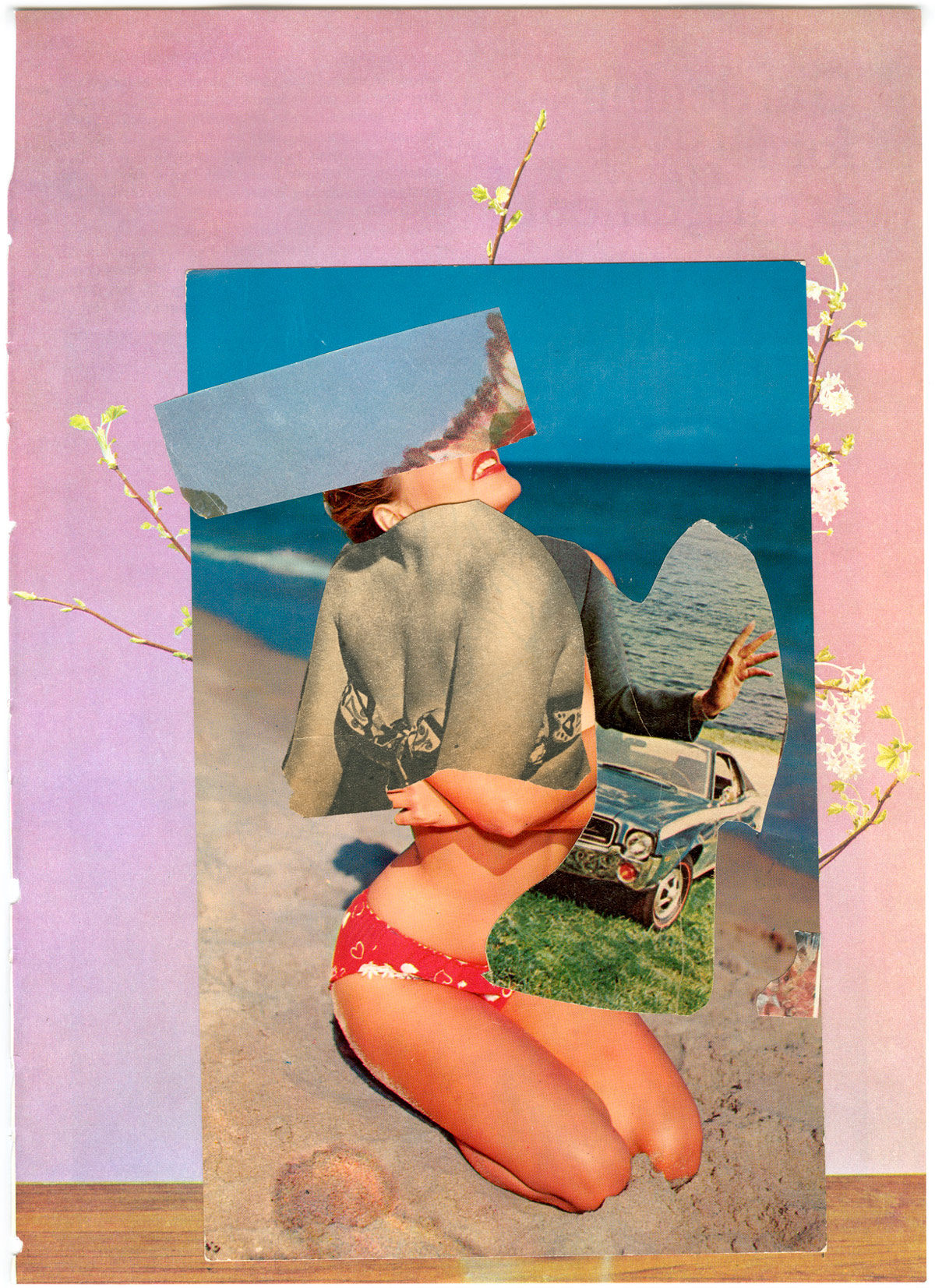

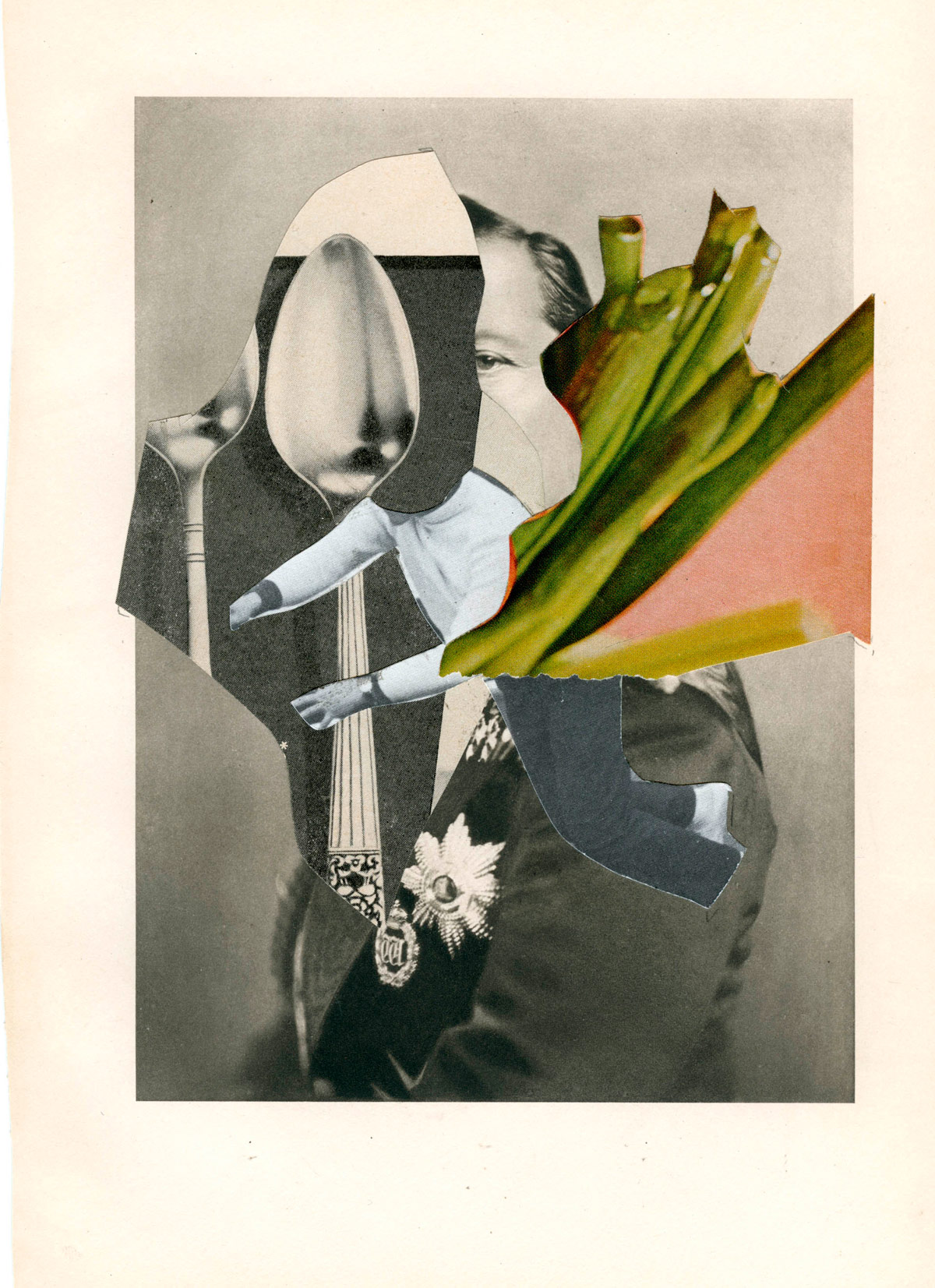

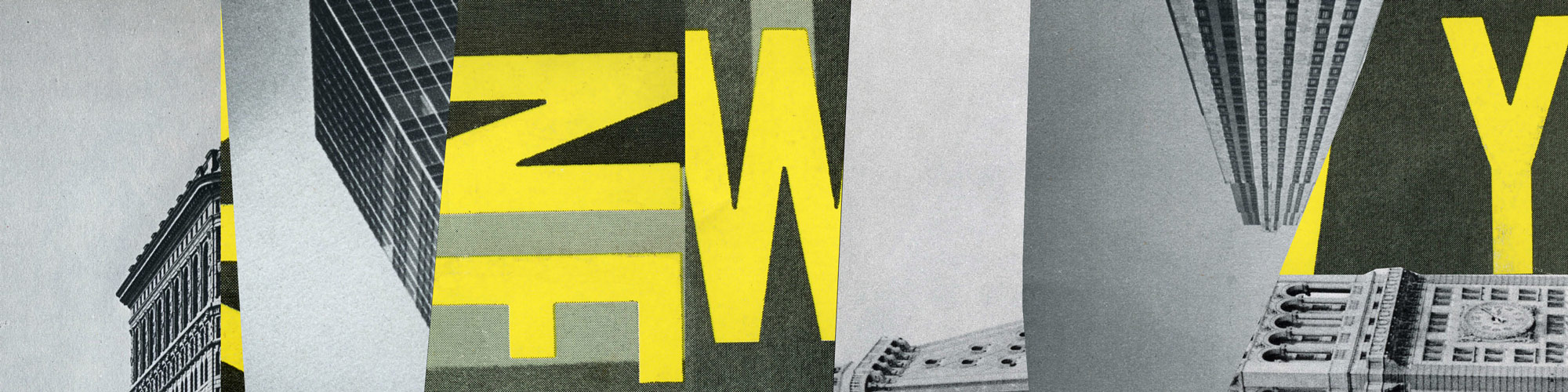

The collages began as a personal project that I posted online anonymously. With book covers, you design within the same format over and over again—on a computer. Doing the collages was a way for me to explore the format without any conceptual restraints, getting away from design thinking and just working with raw forms, real paper, and my hands. I posted them online as a way for me to look at them and keep myself motivated as I posted for my imaginary audience. That progressed into being “discovered” and asked to do some illustration projects. Making it a commercial venture kind of cut into the personal part of it, but I presently have this awesome side gig creating a weekly collage for the New York Times Book Review.

Cool. What advice would you give to someone starting out?

I generally tell young people starting out that they need to over-deliver ahead of time: they have to bust their asses. It’s tough out there! There are thousands of designers going out into the world every day, and you think putting one thing up on the wall is going to cut it? No! If someone calls you for a job and says they need sketches by Friday, send them sketches by Wednesday and send twice the amount they asked for. It’s really, really hard work, and it never really gets easier. There are other pieces of advice I could give, but that’s what I say whenever I have to dress down my class. You’ve got to put in the time.

Do you get a sense that students believe they’re guaranteed a job once they graduate? Did you think that when you graduated?

I don’t know. Sometimes I sense a kind of entitlement in students, as if they assume that if they can just get through college, then they’ll start their own design firm and make millions. But the good students push themselves. Some people are scared about going out into the world to find a job because it’s hard, other people kind of expect something, and other people are working hard to do whatever they’re doing.

When I was in college, I thought I would get a job doing something once I graduated. I’m the kind of person who thinks that once I move on to the next level, I think I can always fall back on the previous level. Should things not work out, I can always go back to the grocery store sign painting thing!

We’re brought up to think that the standard path is to decide what you want to do while in high school, go to college for it, get a degree, enter your profession, and work your way up the ladder. So many people who I view as successful didn’t take that path. So many have said, “I fell into this job,” or, “This didn’t work out, so I had to figure it out before I ended up on the street,” or, “I took this opportunity, even though it was a risk.”

There is even less time now to figure your life out. It used to be that you could go to college and figure everything out there, but it’s not like that anymore. When you go in, you have to focus. You have to pretty much declare your major at the outset. It’s a little scary.

Tina: I can learn on my own if I need to, but I do like the interaction that happens in a classroom setting. [TO BERMON] Are you self-taught?

Bermon: Yeah, I didn’t like the classroom setting, and I dropped out after a few years.

Tina: Certain personality types seem to do better outside of a traditional school setting. There are some things you need to go to school for, but school is often about paying to be around contemporaries and peers as well as having mentors and opportunities.

That’s the advantage of design school, but its not for everybody. The setting, the critiques, the back-and-forth—that’s important for a lot of people, most people. But its not astrophysics either. There’s not a lot of book learning. A really motivated person with the right DNA can probably figure it out on their own. I know plenty of self-taught designers, although they usually had a good mentor in there somewhere.

There are also more opportunities to learn online, though.

People learning from each other in online design communities is something new, and it will be interesting to see how all of that pans out. Will there be a lot of the same work? Will it go anywhere? There’s a lot of pushing each other along, but you need someone pulling you from the top.

It’ll be interesting to see how college design programs evolve.

There are just more and more design programs now. Every school has a design program, and I don’t know where all of those designers are going to go or what they’re going to design. There are certainly plenty of things that can be designed, but—

Bermon: In the design industry, there isn’t a surplus of good designers. A lot of the folks I’m seeing now are junior-level designers who don’t know how to critique others well and who get offended when you critique their work. They kind of shut off. It’s hard to find someone who actually thinks about design as solving a problem or providing something useful, as opposed to making something look nice.

Right. I would expect that to be a real challenge, but it’s always a challenge to try and find young, talented people. I happen to have a bit of a pipeline because of SVA. To a degree, the people who get into the publishing industry have to love it because they’re not going to get paid a ton of money. You have to love the look and feel of type on paper. And books are graphic design objects that are out there in the world, waiting to be seen. At the beginning of every semester, I urge my students to pursue motion or interactive or anything but the printed book. It’s a bit of a litmus test for them.

Tina: Moving on, how does living in New Jersey influence your creativity or your work?

(rolls eyes) I don’t know if it does; it’s just where I live. My commute is about 30 minutes to Midtown by train. I live in the “new Brooklyn” according to the New York Times. There are a lot of designers and media people out here. My wife and I have two kids, so it’s great for them. Working in a city absolutely influences me because there is a constant energy. There is that city vibe and so many amazing, talented people are 10 minutes away from each other. Home is a respite from all of that.

Between your life in New Jersey and your work in New York City, is it important to you to be a part of a creative community, or a community in general?

Working in a publishing house means I’m working with a group of creative people all the time. I work with designers, editors, and writers. Then there is the greater book cover design community where everyone kind of knows each other, and that’s fantastic. Each year, AIGA used to put on 50 Books, 50 Covers, and it was the one time you got to see other book cover designers. Another component is the online creative community where I’ve met all of my collage artist friends.

What does a typical day look like for you?

Making a book is an incredibly detailed project with a lot of moving parts and people with different agendas. My job is to get the right designers on projects and keep them pointed in the right direction. I get to the office around 9:30am and spend the morning emailing. Then it could be a variety of tasks: small meetings about various projects, reviewing designs, presenting designs, hiring photographers, going on photo shoots, checking on the new website design, the occasional big meeting, thinking about the Abrams brand. I usually eat lunch at my desk and then it’s on to reviewing proofs, discussing new projects, and trying to get books to the printer. The days go by very quickly and I don’t usually get to sit down to design until 4pm. On days I teach, my class is from 6–9pm, so I don’t get home until late. I eat dinner with whichever parts of my family are home. If I have any energy left, I might poke around on some personal projects, but I’m more likely to watch a baseball game on TV.

I have found that my train commute is a good time for coming up with ideas because I’m not anywhere in particular, and I don’t have to be doing anything. It’s kind of like being in a decompression chamber.

How many books do you work on at a time?

We publish between 100 to 120 books a year, and we probably work on half of that at any given time. I have a staff of 7 people, including a couple freelancers and an intern. It takes about a year for a book to go from manuscript to publication, so there is a lot to keep an eye on.

Is there any music that you’re listening to right now?

I have tons of records, CDs, and downloads, and I barely get to listen to a fraction. Right now, I’ve been buying almost anything I can get my hands on from the Numero Group label. They reissue super obscure music by old funk, soul, and psychedelic bands. I’ve been listening to a jazz sax and flute player, Yusef Lateef. I am also liking the band Foxygen—they’re these young, obnoxious, Los Angeles kids who kind of sound like every Rolling Stones record from the 1970s played at the same time. It’s really good.

Do you have any favorite movies or TV shows?

I watch all the HBO shows and stuff, but I’ve been watching Trailer Park Boys lately.

Bermon: (laughing)

Tina: I haven’t seen that, but it seems like Bermon has.

[to Bermon] Do you think it’s good or bad?

Bermon: It’s good in a bad way.

Tina: In a guilty pleasure sort of way?

No, a guilty pleasure is more like Storage Wars or something.

Ah, so you watch that, too? (laughing)

I do watch Storage Wars. I like any kind of get-rich-quick, American Dream, find a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow show.

Trailer Park Boys, on the other hand, is—(laughing) I don’t know. It’s a perfect warping of the classic American sitcom, even though the show is Canadian—figures. The premise of it is like every sitcom ever: three losers try to execute some crazy get-rich-quick scheme only to be foiled by their own incompetence. It’s like a Yogi Bear cartoon, but with profanity, hashish, and kids throwing bottles at people.

Oh my gosh. Okay, do you have any favorite books—or favorite books that you’ve designed covers for?

It’s really hard to choose a favorite book. I’m getting into Graham Greene right now. My favorite design book from recent memory is a fantastic book called Enjoy The Experience, which is a collection of homemade record covers from the 1960s through 1980s—brilliant, brilliant stuff.

It’s hard to design for your favorite books because there is too much pressure. You’ve probably seen the Nabokov covers we did—that was definitely one of my favorite projects because I didn’t have to design all of them. I was able to let other designers create something within a certain framework. It was funny when I contacted people for the project; some said, “I’d love to do it, but don’t give me this book because it’s my favorite and I’ll never be able to do it justice.”

I look forward to reading anything new from Haruki Murakami or Jim Shepard, who are two of my favorite writers that I get to design for.

Do you have any favorite foods?

I am in constant search for the perfect pasta Bolognese. If not that, then a deep fried hot dog with mustard and relish from Rutt’s Hut off of Route 21 in Passaic, New Jersey.

What are your favorite foods?

It depends on my mood, but I love pizza. I can eat it any time.

Any kind of pizza?

I’m from the Midwest, so I like the kind of pizza you get there because it reminds me of home. But I also love New York pizza: the big, greasy pepperoni slice folded in half.

Bermon: I’m from the South and am a steak and potatoes kind of person. I can do anything meaty.

Smoked meats! The creation of which is a hobby of mine.

Tina: Well, now that we have that settled. (laughing) What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

I have no idea; it’s not something I think about. It’s the thing one has the least control over. I just hope that my kids will have nice things to say about me.