- Interview by Tina Essmaker June 30, 2015

- Photography by Matt Rubin

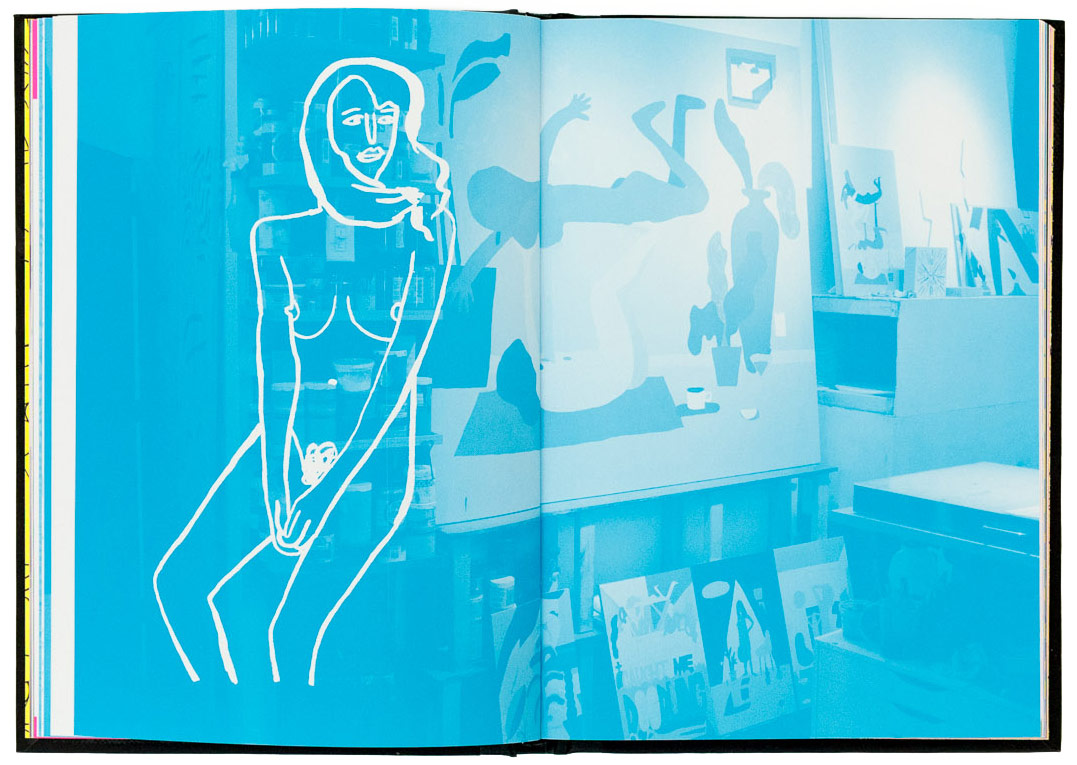

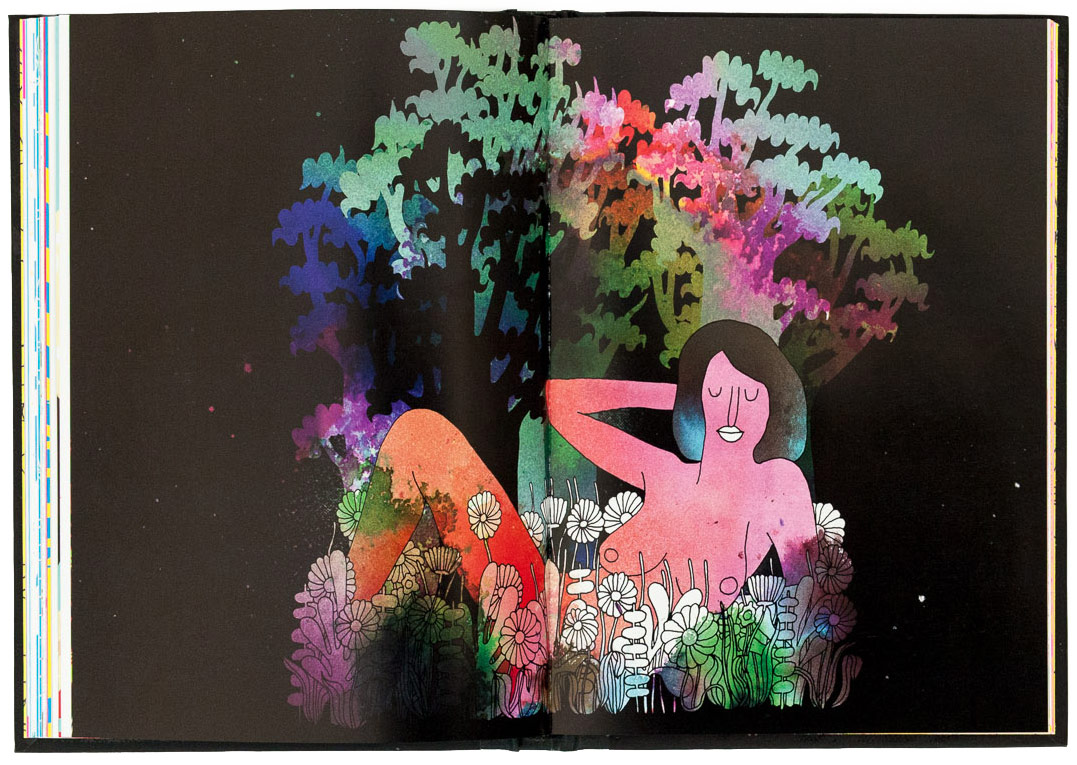

Mike Perry

- artist

- designer

- illustrator

Originally from Kansas City, Missouri, Mike Perry is a Brooklyn-based artist working in a variety of media. He studied graphic design at Minneapolis College of Art and Design and designed at Urban Outfitters for three years before opening up his own studio in 2006. He has published five books exploring everything from typography to the human form, and he has collaborated with everyone from Broad City to Nike, Target, GQ, and Playboy.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now. As a kid, I loved drawing and making things. I did other kid stuff—like running around, getting into trouble, and building treehouses—but drawing was always the most important. Over the years, people supported my interest in art, and that had a huge influence on me. For example, my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Zilansky, observed me drawing and said I was good at it. Being engaged by an adult who tells you that you’re skilled at something is powerful: it’s like getting permission to keep doing your thing. I wasn’t good at school in general, so having someone acknowledge that I was good at something outside of the classroom was life-changing.

I had a complicated childhood. My parents were divorced, and my dad was schizophrenic. I have a brother who is five years younger than me, so I took on the role of an older brother; I was awful to him, but also responsible for him. I grew up in the 1980s during the good ol’ days when people started support groups for children of divorce. I was raised by a single mom and because of that, I had a lot of freedom. I had a different experience from kids growing up today. I walked three miles to school, and it wasn’t a big deal; I often disappeared and ran around at night in the middle of nowhere. But it was a good, safe environment. I had lots of time to learn to be self-reliant. It makes me crazy that kids just can’t do that now.

I had a maternal grandfather, Thomas Williams, who was kind of estranged from our family. He was into science and built weird machines; he was also an eccentric painter who made an insane amount of work. When he died, his house was covered from floor to ceiling with paintings. He gave me a tackle box full of oil paints when I was 14. Even though I had never painted before, it clicked. It was the medium I had been looking for. I started painting all of the time. By the time I graduated high school, I had made 300 paintings and had decided that I was going to be an artist.

After high school, I went to Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) to study art. All of a sudden, I was surrounded by incredibly talented people, and I thought, “Man, I really need to hustle.” I had always been interested in working hard, but I realized that I had to work even harder than I ever had before. I spent all four years of school working constantly.

During my sophomore year, I switched my major to Interactive Multimedia, which involved working with computers. My painting classes had been feeling pretty sterile because we were painting still life after still life. I thought, “My brain needs to be blown right now. I need to learn some new shit.” I had zero math skills, but I realized I could work on the computer without needing math skills. (laughing) That was when I realized that painting wasn’t my path. After that decision, I quickly fell into graphic design.

I was incredibly lucky to have a great crew of teachers and fellow students around me at MCAD. We all thought about graphic design as this ultra-powerful tool that could be used to make anything. It was never about making logos—it was more about problem-solving, concepting, and figuring out how things are made. It was amazing! That’s the moment when I felt like I could do anything. I no longer felt limited by my skills; it became about having an idea and then figuring out how to do it after the fact. That was one of the most liberating lessons I learned. For me, it’s about having ideas and trying to pull off shit that I didn’t know I could. Design is about asking, “What can I get away with? How can I sneak something in that I’ve always wanted to see made and have someone else pay for it?”

Being in college in the early 2000s at the height of vector art, I spent my first year of design education making a lot of bad vector graphics. Then I thought, “This is crazy—I can draw.” I had another skill that I had been denying, and I decided to embrace it. As soon as I did that, my work started to come into its own and make sense. I had acquired a lot of skills over the years by putting pencil to paper, but I never thought about using them to make a living. I wasn’t very forward-thinking back in those days. (laughing) I guess it was more about survival.

Did you stay in Minneapolis when you graduated, or did you go straight to New York? Graduates who study design at MCAD usually apply for an internship at the Walker Art Center. You don’t have to do it, but it’s kind of a rite of passage. I definitely wasn’t the right person to apply—I had a totally different style and aesthetic—but I went for it anyway. The design director, Andrew Blauvelt, wrote a rejection note to me that basically said: “You should get in touch with a guy who used to work here named Andy Beach and work for him at Urban Outfitters.”

So I decided to reach out to Urban Outfitters. As soon as someone told me that working there was an option, I wanted it so bad. I put my portfolio together in a big ol’ box, and stuffed it with weird, original drawings, handmade zines, and a bunch of other important work. I mailed the box off to Urban Outfitters, but I was so nervous about the job that I never, ever followed up. I didn’t even know if my work had been delivered. That box sat in Urban Outfitters’ art department for months.

One day, a guy named Jim Datz, who was starting their web division at the time, walked over to the retail art department and said, “I’m looking to hire somebody. Do you have any portfolios lying around?” They said, “Actually, we have this box of stuff we’ve been meaning to send back to a guy in Minneapolis. You should look at it.” So Jim looked through the box and called me. Two weeks later, I was working in Philadelphia. It was amazing! I would never tell someone not to follow up on an application, but it actually paid off for me in the long run. You can’t plan those things—it’s just the magical ether of the universe. Not having the courage to get my work back completely changed my life. (laughing)

That is pretty magical. How long did you work in Philly? I was there for about two or three years. That’s actually how I met my wife, Anna. When I started, the catalogs were art-directed by Deanne Cheuk. That was exciting for me because she was one of my heroes; I had a total design crush on her. She was there until about 2003, when we hired LA-based design firm, National Forest, to do the catalogs. I met the founders, Steven Harrington and Justin Krietemeyer, and it was super cool. They started bringing all their photographer friends into jobs, so there were all these new, talented people rolling in.

For some reason, National Forest couldn’t do one of the catalogs, so Jim and I were going to do it instead. We were trying to figure out which photographer to hire, and Justin said, “You should check out this girl, Anna Wolf.” He sent her portfolio over, and we thought she was amazing. We brought her on, and she and I hit it off. It was one of the best things that’s ever happened to me. I had dated other girls in Philadelphia, but none of them had any real ambition. That’s how shallow I am—I just want ambition in my life. (laughing)

No, I get it. You need someone who is equally as ambitious as you are, because if not, it’s going to drive you crazy. Right. So I met this awesome, ambitious young photographer. We started dating. She lived in New York already. So we took the leap and moved in together. It was brilliant to have her in my life for lots of reasons. I never thought I’d end up starting a studio or running a business. I imagined that I’d have to work for 20 years until I’d have enough clout to start something on my own. But when I saw Anna running her photo business, she showed me that I could do it, too.

So you quit Urban Outfitters, moved to New York, and immediately started running your own studio? Did you think it was going to work out? Yeah, absolutely. Honestly, as soon as I left Philly and moved to New York, I started getting work. The phone just started ringing and, 10 years later, it hasn’t stopped. Financially, it was easier back then because I worked in my apartment and my overhead was super low. I could live off of editorial jobs. If I made a record cover for a band and was paid $250, I was stoked. I could have gotten a job at a coffee shop to subsidize my income if I had needed to. The stakes were lower and it was very freeing.

I also had an accidental guide to help me navigate the world of freelancing. I didn’t know anything about the business side of it when I started—I didn’t really know what an invoice was. But there was Anna working next to me. She showed me what an invoice was and let me copy hers. It grew from there.

Anna and I worked out of our house in Crown Heights for a while before I realized I needed my own studio. I had done a job with Saatchi & Saatchi for Oral-B Glide dental floss, and I had made a bunch of clay letters to represent plaque on teeth. Some German company made pristine, white foam letters representing healthy teeth. When the job was over, I wanted to keep the letterforms, so a messenger showed up at my house with five massive boxes! I like having stuff. It’s important to me, even when the stuff doesn’t mean anything. But Anna isn’t into having a lot of clutter around, so I hid the letters around the house. One day, I opened an overhead cabinet that I hadn’t been in for a while, and all of those letters poured out onto me. At that point, I knew I needed to find a studio.

When I worked at Urban Outfitters, I had the luxury of walking to work every day. I thought, “If I can walk to work and get a cup of coffee on the way, my life is perfect.” So I wanted a space I could walk to. At the time, Crown Heights didn’t have a lot of studio buildings. It had one, and it’s the building I’m in right now. (laughing) At first, it was Anna, me, and Jim Datz. We moved into a basement space that was awful. Luckily, a bunch of people moved out of the building, so I asked if we could swap. It’s a little bit more expensive than the space we were in, but it’s the best. We built everything out, and it’s become like a second home. I slowly kicked everyone out, so now it’s just me. I have no plans of going anywhere.

It’s great to have a space like that in the city, especially when other things are in flux. I didn’t understand the importance of having a private making space when I first moved into this studio. It seemed like a status symbol: I thought, “Man, I’ve done it. I have a studio.” Over time, I realized that I need a place that’s safe, comfortable, and has what I need to make work. That’s powerful because my brain jumps around quickly and I need to change direction and experiment on the fly.

You spoke about receiving that paint set from your grandfather. Would you consider that the “Aha!” moment when you knew you wanted to pursue art, or have there been other moments along the way? I’ve actually done a lot of reflecting on that. My grandparents were pivotal people in my life. They were important to me.

In a way, my crazy grandfather showed me who I didn’t want to be. I liked his prolificness, but he was fucked up. Once, when I was super young, he gave me a beautiful painting of his. I thought it was the best thing in the world. Then when I got a little bit older, I was looking through an art history book and saw that the painting my grandfather had given me was a copy of a Picasso. I thought, “Don’t let me discover that on my own! Share that information with me!” There were a lot of those instances that made him both a positive and negative role model for me.

One of my biggest “Aha!” moments came from my paternal grandmother. The reason my parents got divorced was because my father was schizophrenic and was a very complicated human being. As kids, when my brother and I visited my dad, the visitations had to be facilitated by his parents. My dad wasn’t always interested in participating, so I spent a lot of time with my grandmother. She was an inquisitive woman; her eyes were wide open, and she paid attention to everything. We went on walks, and she talked to me about the world.

One day my grandmother and I went on a pretty epic walk. We climbed to the top of a hill, sat down, and my grandmother said, “You know, you never know what you’ll discover when you turn something over.” Then she picked up a random rock, flipped it over, and it was covered in quartz and fossils. I thought, “What the fuck?! Who is this person? This is some magical shit!” I don’t necessarily consider that to be the moment I decided to be an artist, but it was the moment when I was given permission to do so. Sometimes all you need is someone to tell you that you can. My grandmother used the power and beauty of nature to show me how much people don’t know and why we have to try new things. That was such a ridiculous moment, and I’ve thought about it countless times since then. How can I recreate that moment for someone else? How do you even do that?

“We want to believe that people are able to just pull themselves out of any life situation and move forward, but sometimes the circumstances around you are incredibly challenging.”

Where did you grow up? Kansas City, Missouri.

What do you think separated you from your peers and led you to believe that you could make a career out of art? As soon as I discovered that art school was an option, I knew I had to go.

So there was something inside of you that knew you had to pursue art? School sucked for me. It was miserable, and I was not good at it. So when I heard about this Mecca called art school where you made things instead of doing math, I was so excited. I should have been going to art school since I was born! I didn’t know how to do it; I didn’t know that it was expensive; and I didn’t know how it worked. But those were details. I could figure that shit out later.

If you can find enough people in your life to help point you in the right direction, that makes it easier. Yeah. One of the big life lessons I learned early on was that the environment you grow up in has a huge impact on what you believe you can do with your life. I lived in Independence, Missouri, during elementary and middle school, and the beginning of my freshman year of high school. It was a poor and run-down town, and it was an environment where college was not an option. Then my mom met someone who lived on the other side of town in Overland Park, Kansas. They hit it off, and we moved there. It was a well-to-do, upper middle-class neighborhood where everyone went to college—it wasn’t an option not to.

Being surrounded by that culture meant that I was going to college, but just a year earlier in another environment, it wasn’t even a conversation. We want to believe that people are able to just pull themselves out of any life situation and move forward, but sometimes the circumstances around you are incredibly challenging. There are a lot of political and social lessons I learned from that reality that I’m still trying to understand and include in my existence.

“What else am I going to do with myself? What’s the point of doing big, commercial projects and making enough money to have a little bit of freedom if I’m just going to fuck up that freedom by sitting on the couch watching TV? There’s shit to do. I have to flip that money and do crazy, awesome stuff with it.”

Definitely. You do what you know, unless you have someone to tell you there’s another option. Absolutely. I ended up at a new school, and the teachers said, “Oh, you want to go to art school? We know how to help you do that.” It was fucking mind-blowing.

I always felt driven to be an artist. I didn’t quite know what that would lead to, but I knew it meant I could keep doing what I was doing. There’s no other option for me. If I wasn’t doing this, I would be in the middle of nowhere, living off $12 a month by making weird, outsider art for people. This is just working out for me right now. (laughing)

Have there been points when you’ve taken risks to move forward? Constantly. I like taking risks; I’m a gambler. Besides, everything is a risk. For instance, if you want to have an exhibition, you can do it one of two ways: you can draw something on pieces of paper, pin them up on the wall, and walk away, thinking, “That cost me $5.” Or you can be super pro about it and spend $20,000 setting it up, doing the right PR, and laying all your cards on the table. You have to find the takeaway from observing the immediate response to your work in a physical space, whether you made your money back or hosted a great party or sold all your pieces. Whatever happens, you need to be ready for the consequences.

We had a show in London in November, and I invested shitloads of money into it. It was supposed to be for a book release, but the small publisher we were working with dropped the ball. All of a sudden, the project I had spent eight months of my life on and put thousands of dollars into was on the line. There was no book to release, and I fucking freaked out. That’s the gamble.

The flip side of that is you when you walk away with something new. The Wondering Around Wandering project I did in 2012 was a massive risk. We raised $30,000 on Kickstarter, which was awesome, but that money was gone in five minutes.

What a lot of people don’t realize about Kickstarter campaigns is that everything is budgeted out and accounted for, so you don’t make a profit from running one. Exactly. That’s the game.

That’s the risk you take when you love what you do and want to do more of it. What else am I going to do with myself? What’s the point of doing big, commercial projects and making enough money to have a little bit of freedom if I’m just going to fuck up that freedom by sitting on the couch watching TV? There’s shit to do. I have to flip that money and do crazy, awesome stuff with it.

There are always risks. For example, I did a big animation project at the beginning of this year, and I was at a crossroads with it. I had two paths to choose from, and I had to weigh the consequences of each. On the one hand, I could have done the project the way I knew how, which was by hand. That takes a long time. The other option was trying to learn something completely new and risking not figuring it out immediately. That was the situation. The time crunch was so intense that if I pretended to learn and didn’t, I was fucked. But I chose to do the latter, even though I was uncomfortable with it, and now I have this new, powerful skill that I didn’t have before.

Keep evolving, keep pushing yourself, keep thinking, and keep growing. You have to stay on top of it. I always assumed this work would become easier as I grew older, but it becomes way more complicated. It’s awesome, though; it’s liberating. If I could make this shit with an automated machine and just kick back, I would be bored out of my mind.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger than yourself? Yes, but as a human first and an artist second. Building a relationship with my community has been one of the most powerful experiences I’ve had. When you grow up in the Midwest, everyone talks about New York City as this big, cold, scary place where nobody talks to each other. But then you move here and realize that that’s insane: every time you walk outside, you’re surrounding yourself with people. Midwesterners don’t do that.

We’re very guarded in the Midwest. We have personal bubbles. Right. When I moved to New York and got my studio, I started walking to work every day. As time passed, I started to get to know people. There is nothing more beautiful to me than walking down the street, seeing my neighbors, and recognizing people. Being part of a community has made me think about the different relationships that make up a neighborhood, what gentrification really means, and what that does to a community. As you grow older, you gain perspective about what’s happening around you. All of a sudden, you start seeing how your neighborhood works, and it’s fucking powerful. It has really opened my eyes to the fact that this is happening everywhere and that it’s complicated. I spend a lot of time in my studio, so it’s easy to forget what’s happening outside. I don’t hit the streets and volunteer in other neighborhoods, but I’m all about being a part of my community. I was recently asked to do a Clinton Hill mural, and I almost felt like it’d be cheating on my neighborhood.

Are you creatively satisfied? Yeah. The projects I’m getting are more complicated, but they have more resources. I’m in a good learning place right now, but I want to do more. The reality is that in order to do the work I want to do, I have to work all the time. I’m not satisfied by only doing something for somebody else—I have too many ideas for myself that I have to fight for. I try to wake up and go into the studio as early as possible so I can work for four or five hours before anyone bothers me. The biggest challenge right now is trying to figure out how to balance it all.

What piece of advice would you give to someone starting out? Keep going.

Is there anything you wish you would have known when you were starting out? Save your money. (laughing) It’s important to invest in long-term, big-picture stuff when you’re young. Anna and I bought our home in 2008, and I definitely was not prepared for what that meant or what kind of stability that would bring into my life. It’s the most satisfying, safe thing that I have in my life. We invested early and we own it. Like I said before: if I hadn’t done this, I don’t know what I’d do. Making that early investment wasn’t about stuff or fun—it was about practicality. If you make those kinds of moves when you’re young, you start seeing the longevity, power, and freedom they will give you. My advice would be to save all your money and buy a piece of property, but avoid bad interest rates and subprime mortgages. (laughing)

You have to make money to live in this world, especially in New York City. There’s that old saying, “Commerce follows art.” I feel like there should be some sort of special loan just for artists, because they’re the people going to environments that no one else wants to be in and making it interesting. Artists are willing to live wherever they can afford the rent.

How does living in Crown Heights influence your work or creativity? I don’t know if it influences my work specifically, but we’re close to the park, which is liberating and healthy. I’m also close to the Brooklyn Museum, which is a resource I don’t take advantage of enough. What Crown Heights provides is a good community and ease of life in a crazy environment.

What does a typical day look like for you? It depends on my headspace. I’m in a really good spot right now. I’m doing some good projects, but they’re not aggressive, so things are chill. I was able to go out last night, which I haven’t done for a while. Anna and I took our dog to the park this morning, and I’ve actually been sitting here since then. I had a delicious smoothie and a burrito, and I’ve just been drawing and watching Seinfeld all day. (laughing) But when my workload is heavy and there’s a lot going on, I don’t have the brainpower for anything beyond the project in front of me. Those days are crazy—they start at 4:30am and don’t end until 7pm or later.

Do you have a mix of personal and commercial work, or do you try to limit the amount of commercial projects you do at one time? It depends on what the day looks like. I’m fortunate in that I probably do half personal and half commercial work. I’m super stoked that the commercial work I do is fucking awesome. Today I’m working on a map of Brooklyn that is massively time-consuming. I’m now in the phase where it’s about putting in the man hours: it’s not overly creative, it’s just drawing, drawing, drawing. But this map is going to be insane. I can already tell that it’s going to be one of the best drawings I’ve ever made. It’s amazing that someone is paying me to do it.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave? I want to show people that the world is a beautiful, powerful place where you can be yourself and make whatever you want.

“I want to show people that the world is a beautiful, powerful place where you can be yourself and make whatever you want.”