- Interview by Ryan Essmaker July 17, 2018

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Noah Kalina

- photographer

For more than fifteen years, Noah Kalina has carved out a freelance career that manages to strike a balance between fine art and commercial photography. Here, the Barryville, NY-based photographer talks to us about the path he took to get there—the high school awards that gave him the confidence to keep taking pictures; attending art school, and jump starting an independent career by taking $20 head shots out of a small Manhattan apartment; and why he chose to move his life and studio to rural Upstate NY. Despite the ups and downs that working solo can often present, Noah still says he wouldn’t have it any other way.

What did your path to becoming a photographer look like? It started in high school. I got into taking photos in 10th grade when I had this teacher who, looking back now, wasn’t that great of a teacher, but was definitely a cool teacher. All of my friends took his photography class, where you just got to hang out, use the dark room, and take pictures—it was fun.

My friends in high school were into music and art. I tried to get into music, playing bass in a band, but it was pretty clear right away that I wasn’t very good at it. I love music, but the language of it just didn’t make sense to me. Photography was different. It was definitely something that just worked. I remember the photos I took at that time really well—I was into landscapes, with a little figure in the background—essentially, I still make the same pictures as I did back then.

My dad also really encouraged me to pursue something I liked doing. He bought me my first camera.

It sounds like he was trying to help you find a creative outlet. I think he knew I wasn’t the type of person who could have had a normal job. It came more from that parental perspective, where you ask, What is this person going to be when they grow up?

(rooster crowing loudly) That’s the rooster. (laughing) Marcel! We’re trying to record an interview here. I mean, come on.

(laughing and talking to Marcel) It’s not your turn to talk! I don’t know for sure why my dad thought photography could be a good career path for me. I think he encouraged it, in part, because he had always wanted to become an artist himself. But because of his parents and how he was raised, he ended up becoming a psychologist. That was just the path; as a first generation Jewish guy from Brooklyn, you’re sort of pushed to be a doctor or a lawyer. So that’s where he ultimately ended up.

I’d normally ask if your family encouraged you to pursue a creative path, but it sounds like they very much did. It seems like your dad wanted you to at least have the opportunities he didn’t. Absolutely. And I think he’s very proud of me. I have a good relationship with my parents; it’s not like I had to run away to become a photographer because they didn’t “get it”.

Aside from your parent’s support, what led to your decision to continue studying photography? There was a photo contest in high school that I entered some pictures in, and I actually ended up winning in two categories: first place, and best in show. That was the first, and last, time I have ever won an award for photography. (laughing)

Wow. I’ve had just enough encouragement to keep going. After winning those awards, I decided that I’d go to art school and major in photography.

What was that experience like for you? I’d tell people I was going to become a photographer, and they’d say things like, “So, what are you going to do with that? How do you expect to make any money?” I think people try to put you down, and to discourage you when the path isn’t clear or obvious. But for some reason, I just didn’t care. I always believed there was going to be a way to make money doing photography; I never thought it was completely hopeless. And the enjoyment I got out of photography was so good, I just thought, Whatever! I’ll figure it all out eventually.

I recognized there were paths you could take that were potentially lucrative, so I figured I could be an artist, but also do more commercial-type work. I didn’t have any real goals, though, because I didn’t really even know the full extent of the possibilities available to me. It’s not like it is now, where you can just do a Google search to see every single photograph that ever existed. When I was in high school, Cindy Sherman and Ansel Adams were the only photography books in the library; it seemed to me that there were probably 10 photo books that existed! It wasn’t until I got to school that I became exposed to more photography, and understood what was possible.

“There was a photo contest in high school that I entered some pictures in, and I actually ended up winning in two categories: first place, and best in show. That was the first, and last, time I have ever won an award for photography. (laughing)”

Did you have any mentors in art school, or photographers whose work influenced you? When I was about 20, during my sophomore year in art school, I found a David LaChappelle book and thought, I’ve never seen anything like this. I can’t even believe what I’m looking at! Photography is totally fucking insane … there are so many cool things you can do. It was incredible; the colors, the production. I had just gotten Photoshop on my computer, so after that, everything I was doing ended up having the saturation bumped way up. (laughing)

There’s also an artist named Jan Staller, who I saw speak at an SVA lecture. He made these otherworldly landscape photographs at night. I was really into that kind of work at the time; it totally inspired me, and influenced the ways I shoot.

That’s what you go to school for, though, right? It’s not always about the technical classes. It’s about the people you meet, and the things you get introduced to that open your eyes to what exists in the world. I took classes in everything from art photography to the more commercial aspects of photography, like studio head shots, because I figured that could be a way to make a living.

“…people try to put you down, and to discourage you…But for some reason, I just didn’t care. I always believed there was going to be a way to make money doing photography.”

How did you end up doing that? I was living in a little apartment in Manhattan, and decided to put out an ad on Craigslist for $20 head shots. I got kit lights, and had a wide-angle lens. They were the worst head shots! (laughing) I had no idea how portrait photography even worked, even though I had just graduated with a degree in photography. I think I only recently realized a longer lens is better for portraits.

All of these random strangers started coming in, and I’d shoot them on a digital camera. Then we’d sit down at my computer and I’d make an edit, turn the photos black and white, and then I’d burn a DVD and say “thanks,” and “goodbye”. I would schedule 3–5 people a day. I eventually raised the rate to $40, and then $60. It was pretty good money!

That’s amazing. Yeah! Just from posting an ad on Craigslist.

Around the same time—this was between 2002 and 2004—I got a job photographing bars and restaurants for AOL’s Digital City. It was an online city guide where you could access restaurant listings, before Yelp was ever a thing. They would give me lists of all the new restaurants opening up, and I would just walk all over Manhattan taking photos for the guide. They were these little postage-stamp size thumbnails; like 50 x 200 pixels or something.

I got paid $10 for an exterior shot, and $15 for interior shots. To get the shots, I would just walk into these places and tell them I worked for the AOL City Guide, and ask them if they minded me taking a few photos of their restaurant. They were usually like, “What’s AOL City Guide?” And I was like, “Well, it’s the internet. People look things up on it. You have a listing there, whether you like it or not. Can I take a photo?” (laughing)

I would print out a paper map beforehand, pinpointing at least ten restaurants, because I knew if I could do that many, I would be making a minimum of $100 that day. I would focus on a specific area of the city and just walk around for a few hours. I did that for years, and I learned NY like the back of my hand.

(looking at prints of AOL Digital City shots)

These are great! This was early digital photography, so I’m actually somewhat proud of how they’ve held up.

“I recognized there were paths you could take that were potentially lucrative, so I figured I could be an artist, but also do more commercial-type work.”

Nice. But it just wasn’t enough money, and I wasn’t passionate about that work at all. Eventually, I sold my whole archive to Zagat when they launched online. It was the biggest single check I’d ever gotten. But looking back now, I can see that I probably got ripped off. Being a photographer is to also learn how badly you’ve been fucked over the years. (laughing)

Throughout all this time, I never worked for anyone else, and I never assisted. I just wanted to do whatever I wanted to do, and work whenever I wanted to work. Then I met the College Humor guys, who had the first really big online t-shirt company, and I ended up shooting e-commerce for them. That became a regular, ongoing job. I was making a couple of thousand dollars every other weekend, so that was my bread and butter work. I was able to live in a pretty great studio and take whatever else I wanted that came my way. It also meant I could quit running around the city, taking restaurant photos.

I was also starting to do my own personal projects, and was getting a little more magazine editorial work, and random ad jobs. And then I had a viral internet video, which ended up being a fork in my career.

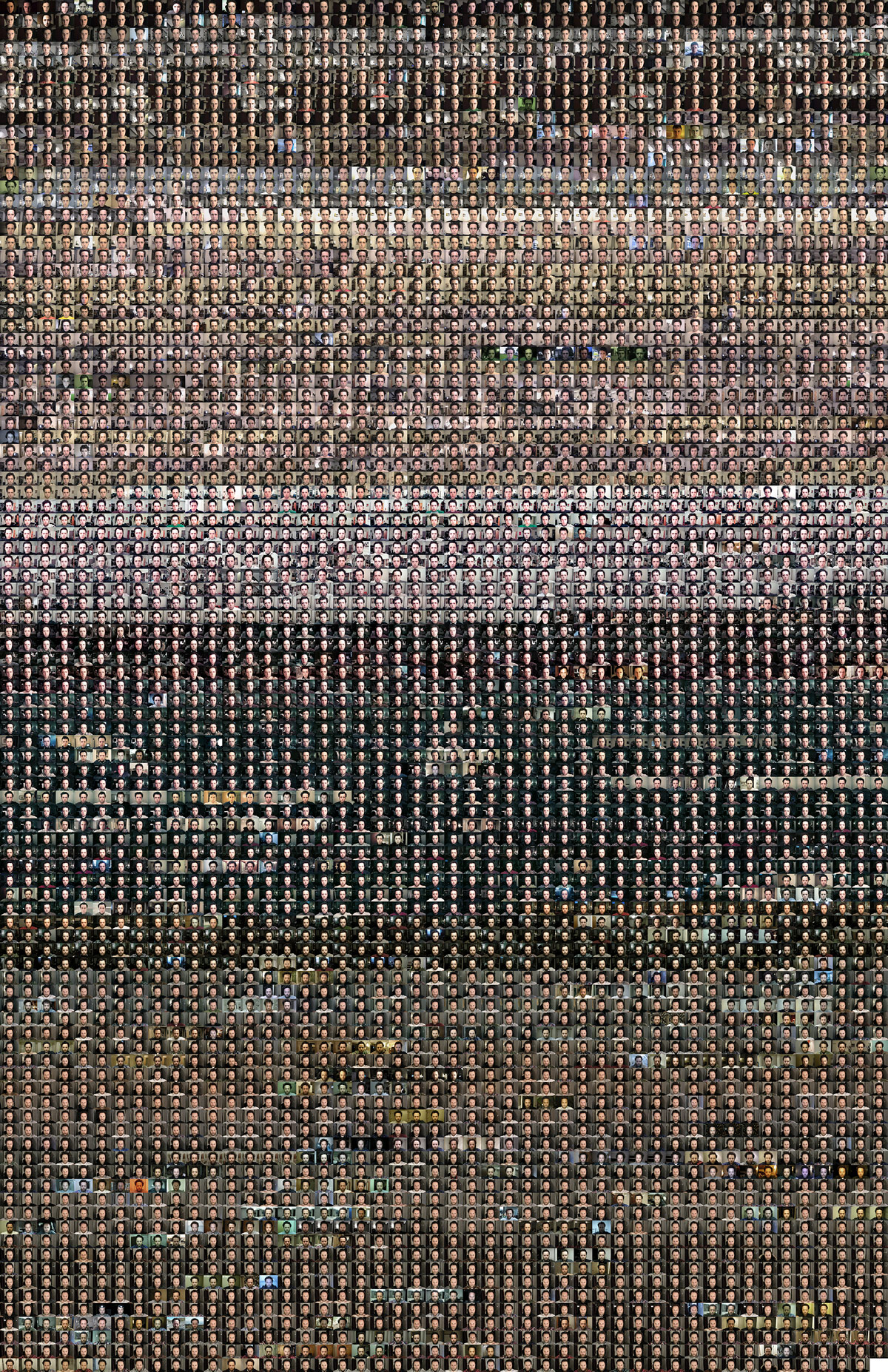

Your documentation video, “Everyday”? Yeah. I started the photo project in 2000 while I was in school, and it became a viral video in 2006. That led to certain things, but that’s its own long story. A little after that video came out, I ended up with the best editorial client—a trade architecture magazine—who had excellent budgets. I would be assigned to shoot random architects in different places around the world. It was great. That went on for about three or four years, so I was able to save a lot of money. But eventually, they just stopped calling.

They spent all their budget. (laughing) Totally! It was also the time of the magazine crash—the world was changing in so many ways. But, that job did help me get to where I’m at today.

“When I was about 20…I found a David LaChappelle book and thought, I’ve never seen anything like this. I can’t even believe what I’m looking at! Photography is totally fucking insane…there are so many cool things you can do.”

Why did you move upstate? I think some people get to a certain point in life and think, Am I ever going to own anything? Or even, Should I? It was a pragmatic decision more than anything. I was traveling a lot, always on the road, and I just felt like I didn’t need to be in Brooklyn anymore, paying $6,500 a month for my live-work studio space. It was an insane amount of money to basically throw away every month. I loved that place and the area, but I always knew I could do better. I had been coming upstate a lot, and I figured my girlfriend and I could just split the cost of this house. It was a fraction of what I had been paying before, and now I own this place with all of this land.

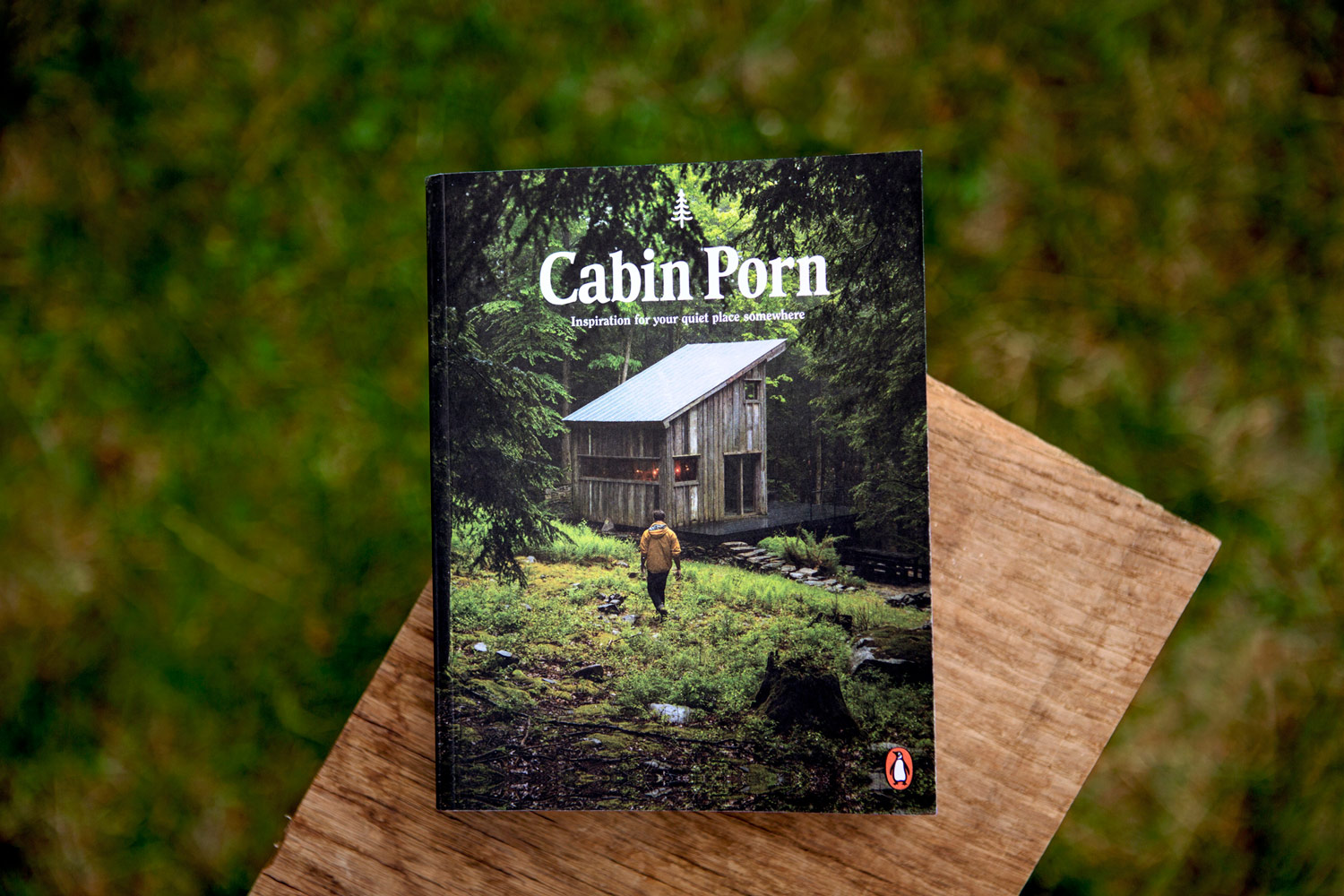

With some of the money I had saved up, I turned the building we’re sitting in right now into my studio. And then Cabin Porn came up, so I was spending even more time on the road. I didn’t need to be in Manhattan for any of that work. And this place is close enough; I could be in the city by tonight if I actually needed to be, which I don’t!

So, no regrets? No, I love it here. Over time—it’s been five years now—I’ve detached from the city even more than when I initially moved. But it’s like the attitude I had about becoming a photographer—I knew I’d just figure it out somehow.

There are dark days, where there’s no work for a long time. It’s a rollercoaster. You can be so low, and then all of a sudden it’s like you hit the jackpot and you’re making a bunch of money again. It’s so much about momentum, too. You get one gig, and then all of a sudden you have five. But when you’re down, you’re down. You get a flat tire, and then you drop your camera, and then you get five bills in the mail—all the shitty things seem to happen at once.

“That’s what you go to school for, though, right? It’s not always about the technical classes. It’s about the people you meet, and the things you get introduced to that open your eyes to what exists in the world.”

That’s life. It is. And, I guess I could always try to get a “real job,” right? But I don’t even know what a real job is. What am I even qualified to do? I have absolutely no other qualifications or skills. I definitely don’t have a plan b. I have no choice but to suffer the lows and enjoy the highs, and accept that my life is a perpetual state of anxiety. (laughing) But I don’t think I could have it any other way.

I totally get that. It’s pretty amazing that you never had any random jobs outside of photography. You just hustled and did what you had to do within the field to make things work. There aren’t many people who can say the same. I feel fortunate, but I did work and suffer emotionally to get through it.

The balance between art and commerce seems to be a thread that runs through your story. Was there any point in time that you felt like you had to sell out? How do you manage to maintain your artistic integrity, while keeping up a consistent look? I’d like to think I have artistic integrity; in the decisions and pictures I make for myself. But in reality, I’ll do anything for money. There’s no integrity there. That said, it’s not like I’m going to show that work, and let it define me.

In art school, I deliberately took both sides. I’m not interested in being poor, or suffering for my art. I approach it from a pragmatic point of view; you have to do things you don’t want to sometimes. You have to take some pretty shitty photo gigs. But what’s the big deal? Even then, you’re a technician of sorts. And I love big photo studios and big productions; they’re so fascinating to me. So, if I can sit in one for a day and punch a button for some money, that’s fine by me.

What other advice would you give someone starting out in photography right now? I think about it from time to time, and I don’t even know how you would start a career in photography now. You get yourself an Instagram account or something, I guess. But just generally, I’d say take a billion pictures. I mean, that’s what I did, and still do. It’s the only way you’re going to learn. And it’s a cliche, but: look at a lot of photography. Find what styles you like, and try to emulate them. You’ll become whatever you are as a photographer out of the mashup of photographers you admire.

Do you think there’s too much of that happening now? Probably. But I do think the cream does tend to rise to the top. Either way, photography isn’t an easy thing to get into. First of all, you have to be completely delusional. (laughing)

And hustle your ass off. Totally. I have to ask myself sometimes if I’m doing the right thing, or if I’m even any good at what I’m doing. You have to question yourself—there’s nothing worse than someone who isn’t very good, but thinks they’re really great. I don’t think I know a successful artist who actually likes what they make and are content with where they are.

“I have no choice but to suffer the lows and enjoy the highs, and accept that my life is a perpetual state of anxiety. (laughing) But I don’t think I could have it any other way.”

Are you creatively satisfied? Currently? No, not really. If I look back at the archive, I can say that I’ve done some very cool things. But when you’re in between projects, you flounder a bit, and have to accept that you aren’t going to be prolific at every moment of your life.

There was a point where I had to step back and engage myself in other projects, like maintaining this property. I felt like I needed a creative hobby that wasn’t related to photography, and I found a great deal of fulfillment from that. Now, I’m in between things again, and I’m asking myself, “What’s next?”

More than anything, though, I’m just trying to achieve basic personal happiness—both as a professional commercial photographer, and someone who makes art photographs.

Does being upstate inspire your work more than when you’re in the city? The work I like to make is usually on location, and that can be anywhere—a city sidewalk, or somewhere in the mountains. But if I had to pick someplace, it would be in nature, away from people. I happen to think this particular part of New York is incredibly beautiful. I’m fascinated with how things change over time, and getting to see it happen up here is really inspiring.

What are your thoughts on legacy? It might be a little early for me to be thinking about legacy. If I died suddenly and unexpectedly, someone’s going to have to go through all of this stuff, and I wonder if they’ll think it’s good, or if they’ll just throw it in a dumpster. That’s what I’m thinking about right now.

“…this particular part of New York is incredibly beautiful. I’m fascinated with how things change over time, and getting to see it happen up here is really inspiring.”