- Interview by Tammi Heneveld January 26, 2016

- Photography by Ryan Essmaker

Rob Giampietro

- designer

- writer

Rob Giampietro is a designer and writer, and serves as Creative Lead at Google Design NY. After graduating from Yale University, he worked as a designer at Winterhouse and Pentagram before running his own studio, Giampietro+Smith. He was Principal at Project Projects from 2010 to 2015. He has worked as a thesis advisor for the Rhode Island School of Design MFA Graphic Design program for nearly a decade, and was the recipient of the esteemed Katherine Edwards Gordon Rome Prize for Design in 2014.

Tell me about your path to what you’re doing now. I’m originally from Minneapolis, Minnesota, and my awareness of design came out of growing up near the Walker Art Center and interning at Target headquarters during high school and college.

Target was important because it introduced me to working in a studio-like environment. I was surrounded by “grown-ups” who didn’t appear to work boring office jobs: they left to go for walks for inspiration or spent the day sketching, and that was fun to be around. Target also had a wonderful design library filled with annuals from the Type Directors Club and Art Directors Club, which would have been totally inaccessible to me otherwise. I spent my days poring over whatever design resources I could get my hands on.

Target and the Walker Art Center were both strong forces of great design in the Twin Cities. It was through their libraries that I discovered a design publication called Emigre. It was incredibly influential in the ‘90s and was somewhere between a fan zine and lively academic journal that focused on discourse and debate about graphic design. The Walker Art Center, Target, and Emigre all added to and helped dimensionalize who I was at the time and what I wanted from my career in design.

I initially got the idea to attend Yale University from Emigre. A lot of the schools they wrote about at the time were overseas, but they described Yale as a great choice in the US. I decided to study in their design program and landed an interview with Michael Rock, who owns the design firm, 2×4, in New York City.

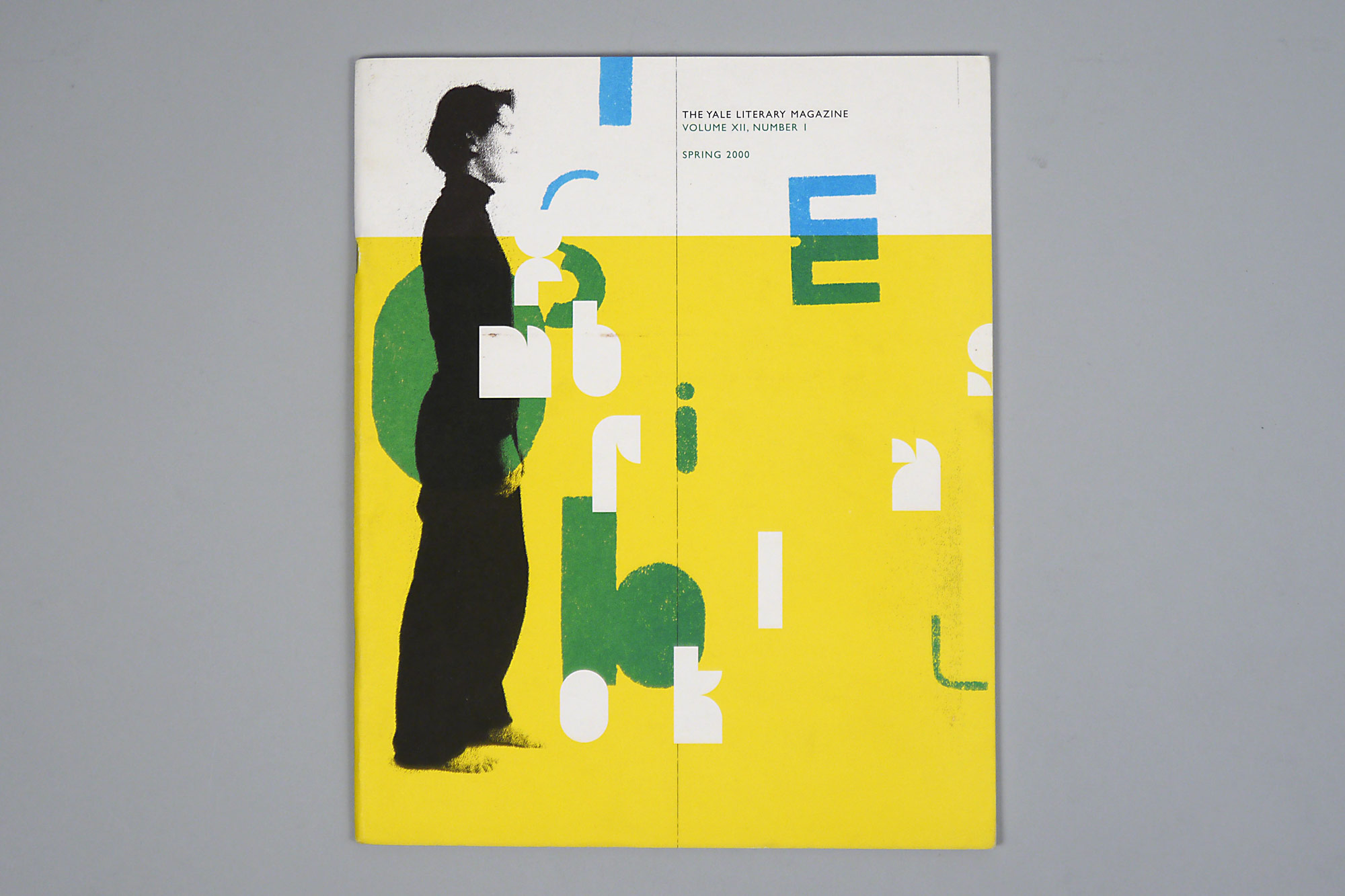

Did you immediately decide to study design in college? Not initially. Once I got to Yale, I cherry-picked a few design classes but stayed dedicated to a literature and writing track. Then I realized that in order to do great design, I needed to fully commit and study art completely. During my last two years at Yale, I studied drawing with a great painter, Robert Reed, who recently passed away. He was an amazing man. I also studied with an important mentor, Paul Elliman, as well as Michael Rock. It was a great time to bring my different interests together and learn how to make design in my own way.

Before graduation from Yale, I thought about studios I could learn from. While attending the 50th anniversary party of Yale’s graduate graphic design program, I met the designers Bill Drenttel and Jessica Helfand of Design Observer. We corresponded after I graduated, and they invited me to work in their studio, Winterhouse.

“As a young designer, the professional work I did was wonderful and interesting, but it often became repetitive. Teaching gave me time outside of my daily practice to reflect and try to articulate why being a designer was important and why my students should care about the problems they tried to solve.”

What a cool opportunity! What was working at Winterhouse as your first job out of college like? I worked at Winterhouse for a year, and I had the opportunity to work on all kinds of amazing projects. I helped research and design Jessica’s book, Reinventing the Wheel; we designed a bunch of books for the Grolier Club, a book-collecting club in New York City that Bill belonged to; and we collaborated with the Washington Square News, New York University’s student newspaper. At one point, I did initial design work for the New England Journal of Medicine, and I worked alongside Bill Drenttel and Michael Bierut, who collaborated on the project.

A year later, I moved to New York City. The New England Journal of Medicine needed additional work done on the journal, so I joined Michael Bierut’s team at Pentagram and worked on several projects there. Around that time, I was given an opportunity to teach at Parsons School of Design through one of Michael Bierut’s partners at Pentagram, J. Abbott Miller. Charles Nix, who ran the program at the time, invited me to teach the “Introduction to Typography” class.

Teaching was an amazing introduction to New York City’s design community, even though at 23 years old, I felt totally underqualified to be doing everything I was doing. As a young designer, the professional work I did was wonderful and interesting, but it often became repetitive. Teaching gave me time outside of my daily practice to reflect and try to articulate why being a designer was important and why my students should care about the problems they tried to solve.

After working at Pentagram, you then opened your own studio, Giampietro+Smith. What led to that transition? There were many independent projects that I wanted to work on. One of my colleagues from Winterhouse, Kevin Smith, had recently moved to the city, and he and I decided to open our studio, Giampietro+Smith. We ran it together for five years. During that time, we worked with many great art galleries and became familiar with people in the New York art scene. One of our main clients was Gagosian Gallery, for whom we designed catalogues and print materials. From there, we started to work for other galleries, including David Zwirner Gallery and Luhring Augustine Gallery.

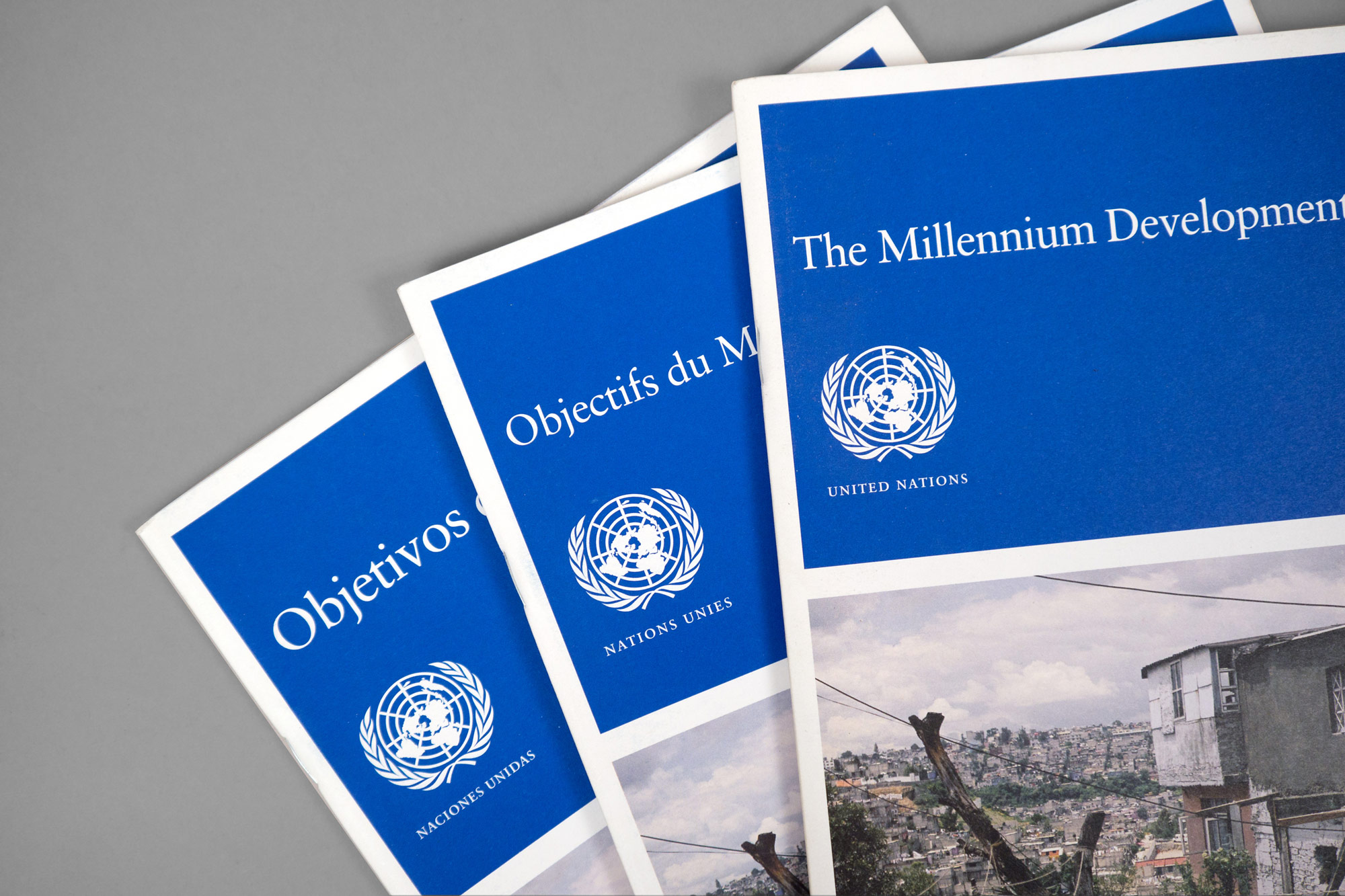

A lot of our bread-and-butter work at Giampietro+Smith came from good causes. We worked on annual reports for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis & Malaria. Through that, we got to work with the United Nations (UN) to design the first comprehensive report on the UN’s Millennium Development Goals in 2005. We did a campaign with the Department of Environmental Protection for New York City, and we even worked on New York City’s 2012 Olympic bid with designer Brian Collins. That was really cool.

And then you became involved with the design studio, Project Projects, right? Yes. Kevin and I worked together until 2008. At that time, I was serving as Vice President of AIGA’s New York chapter. I was excited about doing more organizing, teaching, lecturing, writing, and thinking about my practice in a slightly different way, so I decided to step into freelancing completely for about a year and a half. Some of the projects I took on were too complex or needed more day-to-day input than I could handle on my own, so I reached out to my friends, Prem Krishnamurthy and Adam Michaels, who ran the design studio, Project Projects. They had started around the same time as Giampietro+Smith, and I knew Prem from Yale and Adam through mutual friends in the city. We decided to become partners in 2010.

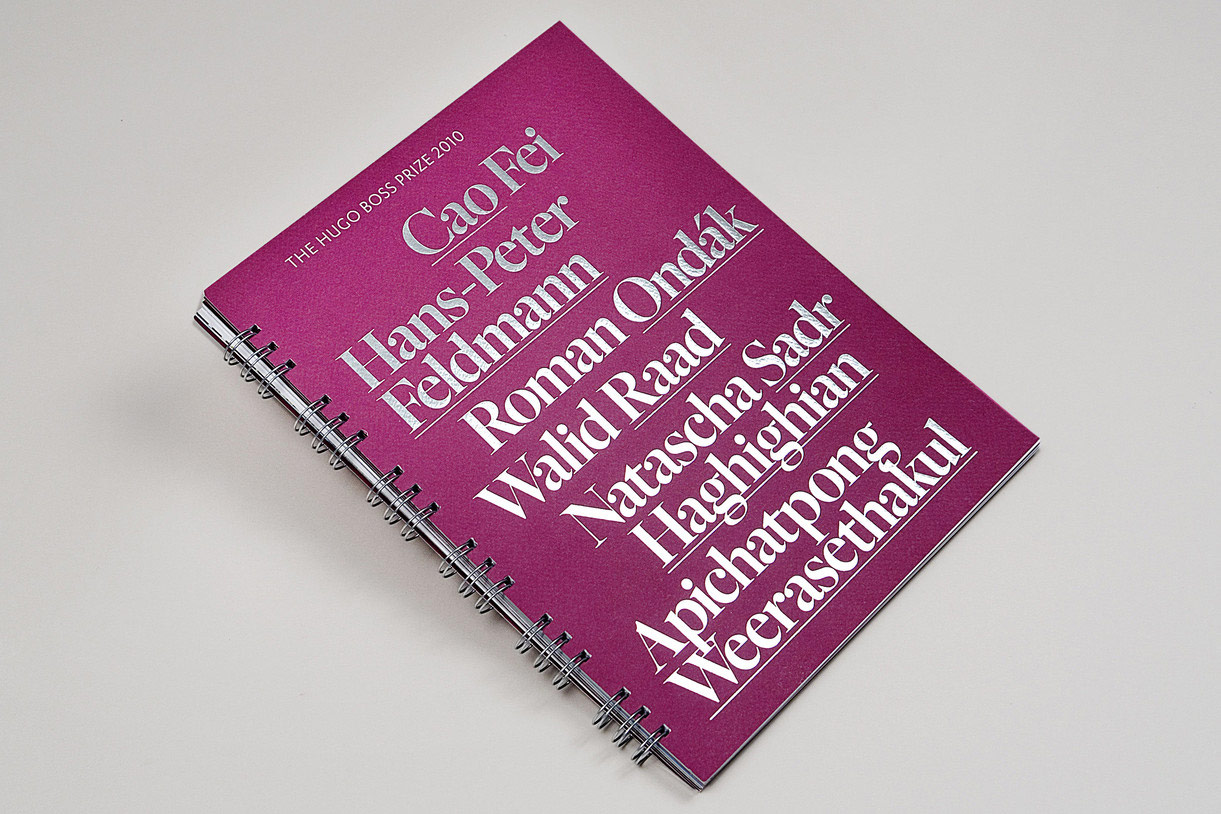

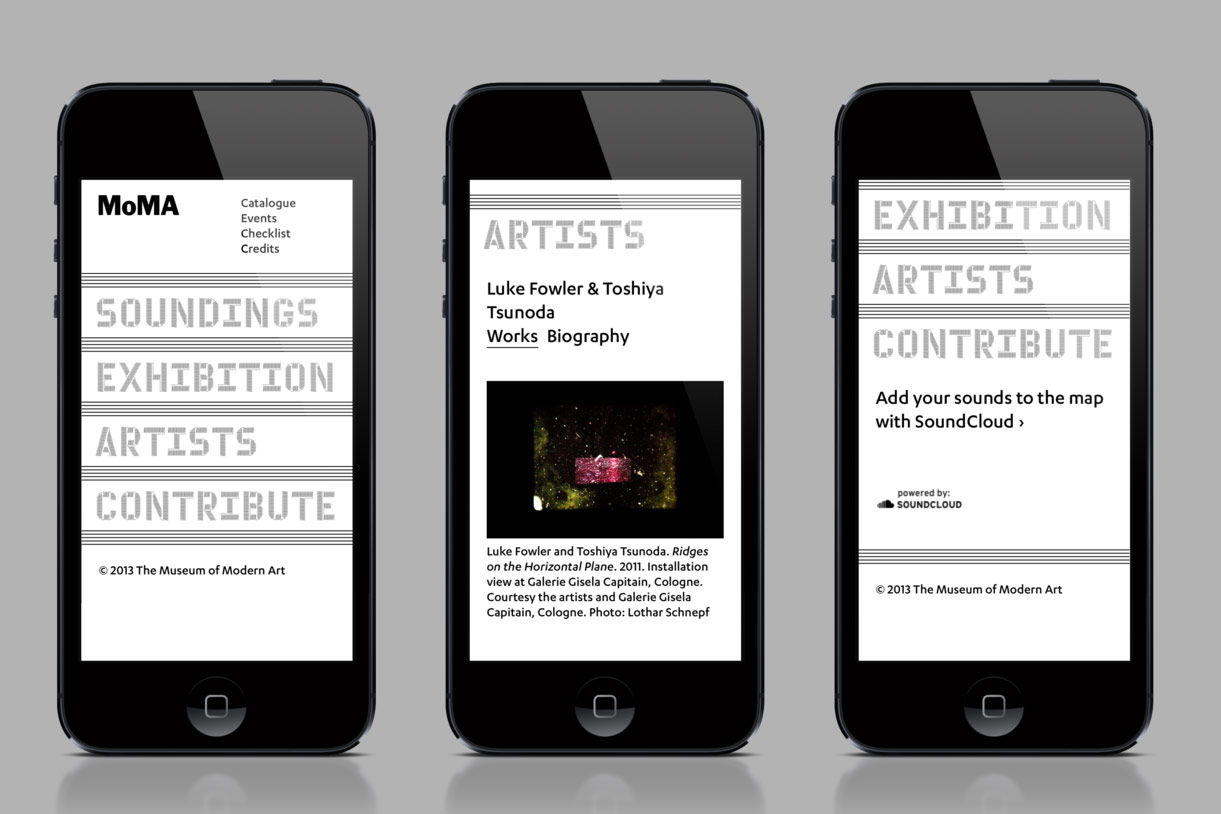

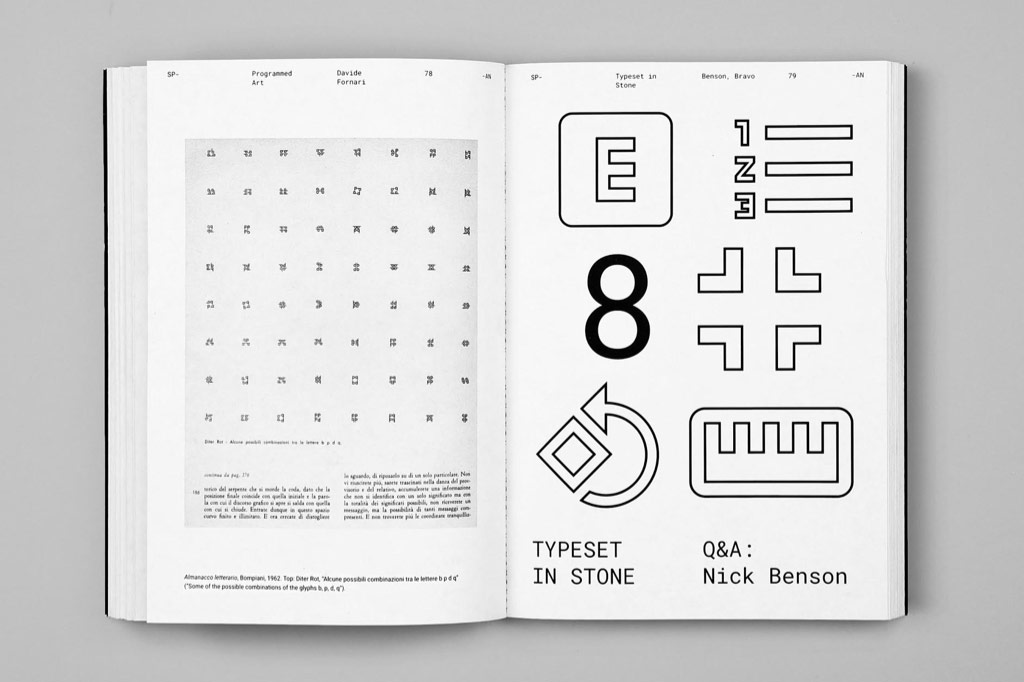

Project Projects was known for exhibition and environmental design work, as well as publication and book design. The first project we did together was that year’s Hugo Boss Prize catalog for the Guggenheim Museum, which was wonderful and fun to work on. Other projects after that included the identity for SALT Istanbul, a new contemporary art, architecture, and research institution, and the identity for the RISD Museum. When I arrived at Project Projects, I was focused on doing more interactive work. They had already been collaborating with artists and architects, so we started making websites for galleries, architecture studios, and similar clients. It was a great time.

I left Project Projects earlier this year, shortly before the studio was given a 2015 National Design Award. I was glad to celebrate that achievement with Prem and Adam, and we were all proud of the studio’s work and that recognition.

What did you do after you left Project Projects? In September of 2014, I became a Rome Prize Fellow and went to the American Academy in Rome for eight months. The Rome Prize has been given since 1906, and it’s an incredible opportunity for artists and scholars to live together for anywhere from six months to two years in an incredible villa on the Gianicolo, a high hill overlooking the city. Fellows are given “the gift of time” and are encouraged to collaborate with one another, with other Romans and Italians, and with fellows from the other foreign academies, like Germany and Spain. Everyone proposes a project and begins working on it, although you aren’t expected to complete it while you’re there.

My project was about getting out of my studio and into the city as much as possible in an attempt to understand how Rome fit together historically and geographically by walking through it with different people. It was a wonderful time, and I wrote about all of it while I was there. In February, at the end of my eight months at the Academy, I gave a series of lectures about the writing I did. I also did a collaborative performance with the composer, Paula Matthusen, that was based on field recordings she made at some of the sites I described in my writing. Since then, I’ve been thinking about how to further develop those essays and how to present it all more formally in the future.

And now you serve as Creative Lead at Google Design NY. Tell me about that. While I was still in Rome, Google approached me to join them in leading Google Design’s team in New York. Google Design is Google’s initiative to support designers, both internally and externally, with tools, resources, and guidelines, along with conferences, articles, videos, case studies, and more. That might sound like an unexpected next step, but while I was in Rome I thought so much about how technology mediates our experiences, and I had been looking for ways to broaden my interactive design practice. I knew Google was a place where I could learn a lot about design from a wholly different perspective. I’ve been here for the last six months, and it’s been tremendously exciting.

I’ve also continued to teach in the RISD MFA Graphic Design program for the last eight years, and I’m very proud of my work with my students.

Wow, you’ve done a lot. Yeah, I feel very fortunate. I’ve tried to learn as much as I can at each stage of my career. If I ever find myself not learning, then I figure out how to keep moving forward. That principle has made for a very rich and engaging career.

Let’s talk about mentors. You mentioned that Robert Reed was a mentor of yours. How did he influence you, and did you have any other important mentors? Robert Reed was an important influence. He was a legendary art teacher—I believe he taught Chuck Close and Cindy Sherman when they were students at Yale.

He taught a basic drawing course that, in part, gave students an awareness of artistic discipline. He told us that no one needed us to make art, so we had to find that drive within ourselves. He had pushed us beyond what might work in other classes and demanded everything we could give, which was critical for people who were on the fence about becoming art majors. Professor Reed taught me the discipline and practice involved in making art, and encouraged his students to make time and space for it in the midst of our daily lives. Otherwise, it wouldn’t flourish.

“…significant recognition takes a long time to earn and is worth the wait. It’s important to have realistic expectations and not let yourself become prematurely frustrated.”

Speaking of teaching, you mentioned feeling unqualified when you began teaching at Parsons, even though you were working at a notable studio alongside acclaimed designers. I felt unqualified because I was unqualified. Charles Nix, who had been teaching the typography class for a while, said to me, “Well, of course you’ve read Daniel Berkeley Updike’s Printing Types: Their History, Forms, and Use?” I replied, “Oh, for sure!” Even though I definitely hadn’t. (laughing) I ordered the book, which is a two-volume, thousand-page tome of type history, and crammed it over a week.

I was terrified to teach the course, but I was also thrilled. I realized that I’ll never learn material better than when I have to teach it. I also realized the importance of students seeing someone not that different in age from them be a practicing designer out in the world. Teaching influenced the way I worked in a studio setting, because as I talked to students, I connected ideas in ways I normally wouldn’t in order to help them understand a point. Sometimes I jotted down what I learned from my students after class, and those notes later seeded essays or other writing. It’s a virtuous cycle: you practice your skills and share what you know. Teaching then stimulates you to reflect on the work you do, and that reflection spurs people to reach out to you to practice in new ways.

You’ve worked for a handful of studios. When you take a new role, do you consider it a risk? Each time I left studios I was deeply involved with, whether as a cofounder or partner, it was difficult and scary. It’s much easier to continue what you’re already doing rather than disrupt it and change. But something deep within me notices when I’m stagnating, and that voice lets me know when I need to find new challenges.

So the risk is necessary to move on to bigger creative pursuits? Yes, although it’s more about growth and curiosity rather than advancement or progress. I need to grow as a designer, and in order to do that, I need to be multifaceted. There’s a tremendous fear that any artist or creative person feels. You have to make decisions in your life about what you can tolerate and what you can’t. I’ve found a good balance, and I’ve been happy to make changes in my career when I recognize the need for them.

That’s good advice. You spend a lot of time guiding students in a classroom. What advice do you give to young people starting out? I actually did an interview with Justin Kropp years ago that included 10 tips for people starting out. I honestly can’t top those pieces of advice! If people are interested, they should check them out.

The tips you give in that interview are pragmatic, which is refreshing. A lot of advice can tend to be more abstract. A lot of it comes from working with students. I was a freshman counselor in college, and as I was being trained I was told, “Students will ask you incredibly granular questions, because one of the signs of being overwhelmed is becoming anxious about very specific details.” I’ve seen that in students over the years, so I felt like the best thing I could do was to give specific advice.

The unspecific advice I would give to people is that your first job right out of school is extremely important, and it is not the time in your career to start compromising. Stick to your guns and do what you really want to do. There will be time later in your career to evaluate if you’re making enough money or being creatively challenged or what have you—but you’ll learn much more about what you want by going after your first choice.

Do you have anything you’d say to your younger self when you were starting out? I have two bits of advice for my younger self. First, I didn’t understand until later in my career how important it is as a designer to listen. That is the first thing I’d tell myself. At Project Projects, I had phone calls with new clients, and at one point I realized that my desire to please them and show them how much I knew wasn’t as important as allowing them to talk and become intrigued by the mystery of what it would be like for us to work together. Even if I had already started to formulate ideas, I needed to let the person bringing the project to me finish all of their thoughts before I spoke. Listening is so important, and I feel like a lot of new designers don’t understand that. It takes time.

The second bit of advice I’d offer to my younger self is to be patient with recognition. It’s important to ask for recognition when you need it and to have good support systems around you, but significant recognition takes a long time to earn and is worth the wait. It’s important to have realistic expectations and not let yourself become prematurely frustrated.

Do you feel a desire to contribute to something bigger than yourself? Oh, completely. One of the fun things about being at Google is that it’s much bigger than me: I’m surrounded by smart people with great opinions and ideas. An important part of working together is being humble with people who have a better or more interesting perspective than your own. Teaching and writing are other ways I like to contribute.

Looking at your long-term contribution to the world of design, have you thought about legacy? I’m tremendously proud of the work I did for the 2012 Olympics bid and the work I did with Project Projects for the SALT Museum in Istanbul. I’m also proud of the work we’ve done at Google around launching the new identity and the conference, SPAN2015, that we held last October. I hope these things are remembered.

I would also like to leave a legacy with my writing. Over time, I hope that it endures and remains valuable and important for people.

Looking back at the last decade, I hope that creative leadership, mentorship, and teaching are also a part of my legacy. The best gift is to teach many designers who will do smarter and more thoughtful work in the future. After almost 15 years of teaching design, I feel like I’m doing pretty good!

“Stick to your guns and do what you really want to do. There will be time later in your career to evaluate if you’re making enough money or being creatively challenged…but you’ll learn much more about what you want by going after your first choice.”