- Interview by Tina Essmaker June 13, 2017

- Photography by Victoria Wright

Robyn Kanner

- art director

- designer

Art director and designer, Robyn Kanner, took a circuitous path to her current work and it began in rural Maine where she grew up. Here, Robyn reflects on her personal journey of transitioning and how it influenced her career trajectory, what led her to cofound MyTransHealth as a resource for the transgender community, why good design should act as a roadblock for bad products, and why she hopes she’ll never be creatively satisfied.

Tell me about where you grew up and how your childhood influenced your ideas about creativity. I grew up in rural Maine in a pocket-sized town called Fairfield. It had one stoplight and there wasn’t a ton of creativity. I ran track and cross country in high school, spent way too much time in my head, and disassociated for the majority of my upbringing. I didn’t have space to express what was going on in my head, you know? And no one gave me a journal and said, hey, you should write about it.

There were a couple of guys in my neighborhood who were in a band together though and they were a little bit weird, so I mostly hung out with them because I thought they were hot and they were doing stuff that wasn’t the norm. I did photography for them, which eventually translated into the question of what an album cover would look like, which turned me onto visual design.

Then I accidentally graduated high school early. I got kicked out of a class and because of that I was able to take a different class and my credits aligned in a way that worked out. I graduated in December instead of in June. That gave me extra time before college started. With music happening in my life and time off before college, I worked the late-night shift at a Wendy’s.

I had a lot of anxiety about what to do with my life. My dad was really sick; he had multiple sclerosis. I figured out I could translate my anxiety into making things, which led to a career doing design. The main reason I learned how to design is because I was anxious as a teen and it was the only thing I could do to get out of my head.

Do you think you made the connection to design through doing the album cover artwork for friends’ bands? Was there an “Aha!” moment when you realized that it was something you could pursue as a career and make money doing? Yeah, it was through music. There was this band called 6gig. They were local, but they had some national traction. Their lead singer was Walter Craven. Walter was really into layers and textures, and I stared at his work all of the time and eventually thought, I bet he makes money doing this.

So you went to college after high school. Did you study design? I didn’t study design. I kind of flailed around and ended up going to four different colleges.

All in Maine? Nah, it was messy.

Life is messy. Tell me a little about the path after high school leading up to doing design full-time. I really didn’t have any tools for dealing with life so I ran away from things. Because of that, I moved around a lot. After high school I went to a community college for history, but that didn’t work out. Then I went to a film school in Bangor, Maine, for a semester. Then I went to a liberal arts state college in Farmington, Maine, which is another very rural town. While I was there, I got really into the art program, but I was still trying to be a designer. I didn’t know that people went to school for design — as absurd as that sounds. I thought people went to school for art and then found their way into design.

I was in Farmington for two years. Then I did a semester in Minneapolis. There I started to freelance. At that point I had enough bands who hired me to do their albums that it became a thing. When I got back to Farmington from Minneapolis I was on my way to finishing college, but I freaked out about gender and had to get out of that small town. I was two classes from graduating when I left to work in the music industry. I helped with booking, tour managing, designing, and photographing for different bands for a few years.

Earlier you said that you did a lot of running away and you mentioned that you freaked out about gender. When did you stop running and embrace who you are, and during that process did you begin to feel more settled in your career trajectory—were those two things tied together? Yeah, but not in a linear timeline—I’m bad at linear timelines. (laughing) I describe my life as if I was driving a bumper car. It was never a clear path.

When I was 19, my dad died. Because he was so sick, it took priority in our family, and I didn’t do anything about gender for a long time. When he died, I carved out space for myself. That semester I was in Minneapolis at age 21, I transitioned. I literally just left Farmington, Maine, and went to Minneapolis and transitioned. I couldn’t get access to hormones because I didn’t look “trans enough” or something, but I was living and presenting as femme and going by a different name while still having testosterone in my body.

When I got to Minneapolis I was basically not hirable—like not even a sales job. I was also addicted to Xanax around that time because it was how I coped with my anxiety and dysphoria. I did freelance photography at this place called First Avenue and they were really chill. One night I shot Conor Oberst and the Mystic Valley Band. It wrapped at 3am and I couldn’t afford a bus ticket to get back to my apartment, so I walked. As I walked, I went through a huge mental breakdown and realized things weren’t working. I was barely surviving. I got back to my apartment, slept a couple hours, and when I woke up, I knew I had to leave.

I hopped on a bus to Chicago where I slept on a friend’s couch for two weeks. I chopped off all my hair and de-transitioned there. This was before I was a person on Twitter, so there were only a few people on Facebook who saw that I changed my name back to my dead name. I de-transitioned because I was literally getting the shit kicked out of me and without the right hormones in my body I just couldn’t make my life work. I went back to Maine and it wasn’t until I was 25 that I transitioned again.

How did you get back on the path you felt like you were supposed to be on? Well, I de-transitioned in 2009, and the way we talked about transness at that time was so remarkably different than how we talk now. There was no language. When people talked about being trans, it was either in intense academia prose caked with words nobody understood or it was consumed by drag culture, which just wasn’t me. That made communicating what was going on with me impossible.

The way I got back on the path was that I quite literally ended up in a hotel on a Friday night and took close to 200 milligrams of Xanax and didn’t remember any of it. I woke up on Monday and wondered what happened. When I got back home I thought about this woman I was really into and dated for a brief, brief second. Her and I were hot and cold for years, and I had historically deflected my dysphoria onto her. Anytime I felt bad about my own gender identity, I wondered if it would work itself out if we dated.

One night when I was freaking out, I texted her—like, a lot. She told me, “Whatever’s going on has nothing to do with me so figure out your shit.” I went home and talked to a friend and he reiterated that. That’s when I had the distinct feeling of, but I don’t want to. I very much knew that transitioning would change everything. I woke up and thought, well, I’m going to die if I don’t do this. I might as well see what happens, so I went to a new therapist and finally started hormones in 2013.

“If the core product doesn’t work and someone is screaming down your throat to ship something, how do you become a roadblock and prevent the bad thing from shipping? To me, that is where really good design happens. I want designers to do more of that.”

And what about the timeline of your design career? I was done with music in 2012. I got a contract working at this little nonprofit and it was all 60- to 70-year old cis white men. I mostly worked there because it was the perfect place to transition because the job required minimal brain activity for me.

When I recognized that I was wasting my time there I started interviewing at other places to see if I could still be a designer, but stay in Maine. In interviews I presented super femme to give them the heads up that if they hired me, I was in the middle of transitioning. They were not into it. They wanted a dude with a beard who would make some vectors and drink beer with them.

There was this one hip design agency in Portland, Maine, and it was the place to work. I was in the last round of interviews with the VP of Design, and she said she had one last question for me. She said, “Can you tell me why you’re the man for the job?” I looked at her and asked, “Do you mean the person?” She said, “No, I mean the man.” I exhaled and said, “I’m not getting this job, am I?” She said, “Nope.” I left that interview feeling crushed. The agency was a few blocks away from the non-profit I was at and there was this one coffee shop called Speckled Ax that knew I was transitioning. I left the interview, went to the Ax, changed into more tomboyish clothes, went back to my job, and was like, “What the fuck am I going to do? This is so bad.”

I was casual Twitter friends with Mike Monteiro, so I emailed him and said, “Dude, I’m in Maine and I do not know what to do right now. I want to design, but nothing is working. I can’t even tell my own job that I’m transitioning.” He sent me this really sweet email back that was like, “You gotta go.” It was all very sweet and sincere, but the root of the message was that I had to leave.

I took a few days off of work, hopped on a bus to Boston, and met with recruiter after recruiter. After a few days, I got an interview at Staples for a long-term contract. I showed up and presented my work like my life depended on it. It was a blunt meeting with this fantastic design manager named Grail. We talked for half an hour about design and then we took the same elevator together down. He asked if I was interviewing at a lot of places and I said yes. He asked who I was going to go with and I said the first person who offers. He asked if I lived in Boston and I lied and said yes, and he offered me the job. I went back to Maine, put all of my shit in storage, and found an apartment on Craigslist in Boston. I bought a $500 car and I drove to and from Staples for 9 months with an uninsured vehicle. That’s how I got my first real job in design.

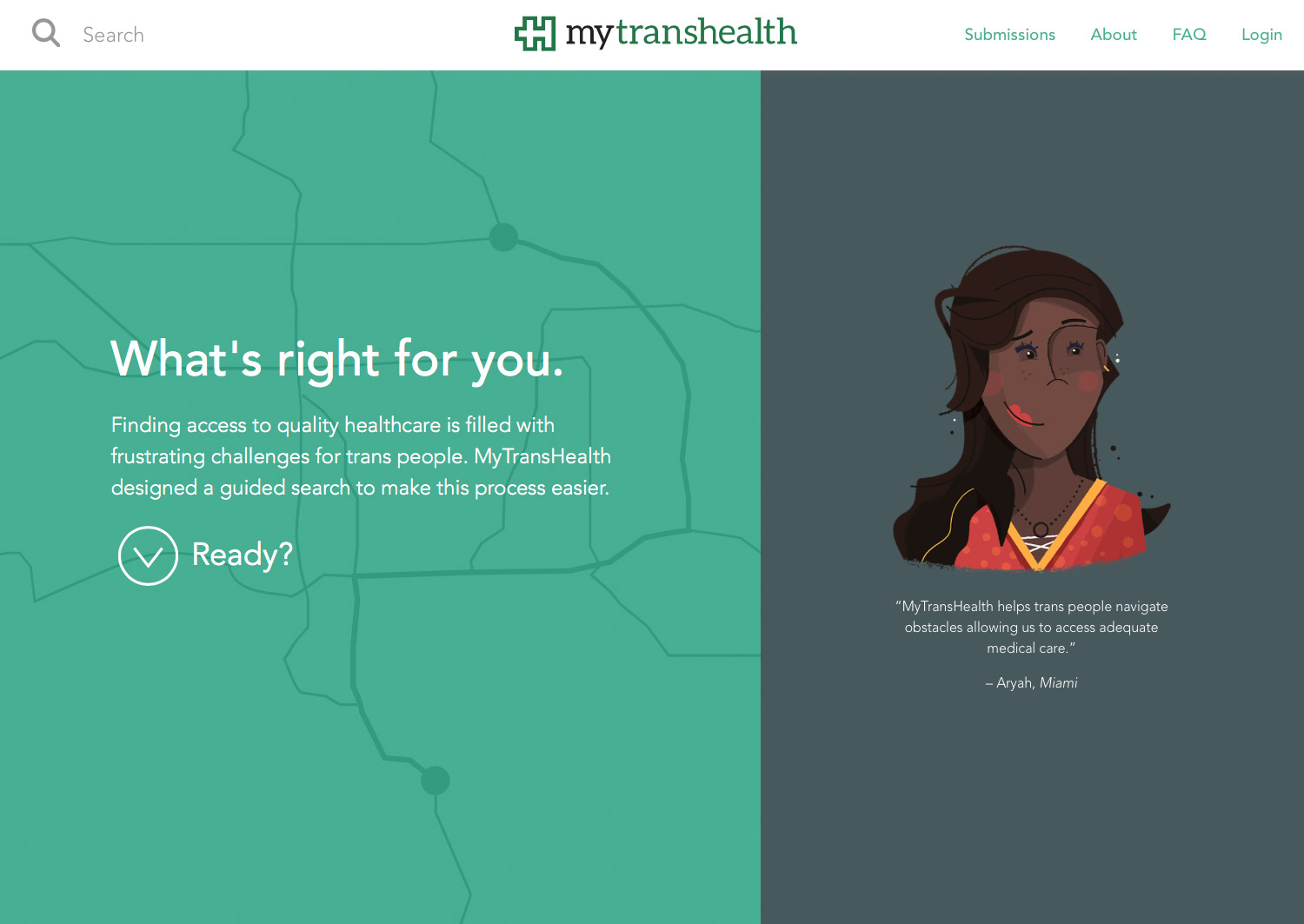

When I was at Staples and my car died, I had to get a job in town. New Balance was a bike ride away so I contracted there for 6 months. Then I moved out West without a job, naturally. I found myself in a wonderfully quaint attic in Portland, Oregon, which is where I designed MyTransHealth. Then I got scooped up by Amazon, which brought me to Seattle.

“I never learned how to be that vulnerable in a relationship because I was only taught to survive…The idea of loving somebody authentically and wholly is something that was never shown to me, and it’s not being shown to trans girls who are growing up right now. What I want people to know is that we need to start telling some fucking love stories with trans women in them.”

And you just announced that you’ve accepted a new position at Etsy in New York. Congratulations! Yes! I’m so excited! I’m joining them as a Senior Product Designer and can’t wait to get started in late June. I did a Design Family Hour with them last year and fell in love with the team, brand, and approach to design. Plus, it’s New York. The West Coast was great for me to heal in, but the East Coast is my home.

Let’s talk more about MyTransHealth, which you cofounded. It helps trans people identify quality providers that meet certain criteria. Tell me how you became a cofounder. When I was in Boston, I got a note from a trans guy named Kade Clark. He had an idea for a health care thing and needed a designer. We got on a Google Hangout and hit it off, but we had no idea what kind of product we were going to make. It wasn’t until we were pulling together the Kickstarter materials that we realized what we were making.

We had done a video for fundraising purposes asking trans people to tell us about their poor experiences with health care. When we put 10 different trans people in front of a camera and they all had a story about a rough experience with health care, I knew we had something that would work. We launched the Kickstarter and positioned it to people who weren’t trans with the idea that we could get people who aren’t trans to fund this thing that people should have regardless. We launched the concept the week Caitlyn Jenner came out in 2015, which was a very conscious decision. The product launched in May 2016.

How many cities is MyTransHealth in and what kinds of responses have you had? This June we hit 20 locations across the country and launched a new site design. We’re excited about it! I remember when the site launched I crawled the internet super hard. I was in a Reddit for trans people and there was a person who had just moved from Thailand to New York and they were looking for a doctor. Someone responded with the link to MyTransHealth with the exact location of the service provider and the insurance they accepted. That was the site working fluidly in the world.

We called every single provider and organization on our site and had a conversation with them about how they provide care to trans people. When your community is historically marginalized, everything comes down to trust issues. It was on us to vet the providers for standards of care. It was an intense process.

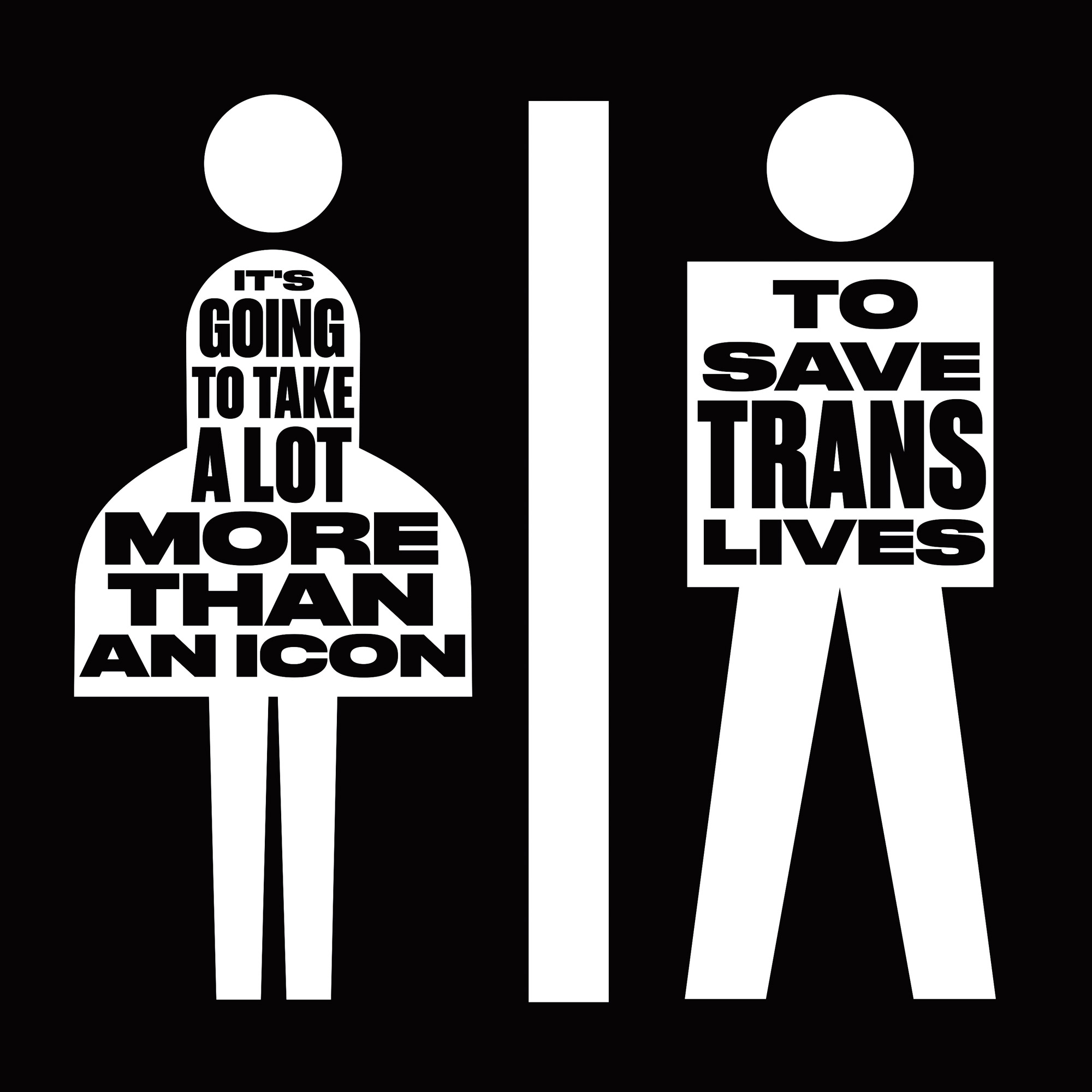

You said you launched the week Caitlyn Jenner came out as trans? Yeah, I have numerous thoughts on her and they’re not super bright. A big reason why we launched the concept that week was Tiq Milan. He’s a fantastic activist, writer, and media person. He gave this talk at the Philly Trans Health Conference in 2015 and basically said we need to Kanye this moment—whatever we can get, let’s take it. That’s exactly what I did. We funded MyTransHealth based off of the general public’s recent humanization of trans lives.

You hijacked the moment for your own press. I love it! So I was watching a video of a talk you did and you were explaining the difference between simply solving a problem and solving it in the right way in relation to your work on MyTransHealth. Will you talk about that? The majority of health care sites pull data together for trans providers, but don’t vet or research it. They’re kind of solving the problem, but not really. How do they know that provider is legit or has a good history with patients or knows how to talk to them about their lives? Their solutions are very surface-level.

It’s the thing where designers think something is good design because the UI is pretty as opposed to getting on the phone with a provider and asking the important questions. That’s what I consider solving the problem in the right way. It’s about the deep dive. I’ve seen designers get stuck on the small details when the core product doesn’t work. You’ve got to pull back into a holistic frame of mind. If the core product doesn’t work and someone is screaming down your throat to ship something, how do you become a roadblock and prevent the bad thing from shipping? To me, that is where really good design happens. I want designers to do more of that.

For example, if I worked in the government right now, I would be finding every way possible to say no to the Trump administration. Anyone who works in government right now and is able to say no and still keep their job is the best designer practicing in this world. That’s what taking responsibility for the work you put into this world looks like.

So you work full-time and have additional projects. You also speak and write. What have you learned from balancing all of those things? I never feel like I’m doing enough. Shifting to Amazon was a big change for me. I freelanced before that and was literally on 24/7. When I got to Amazon, it was interesting because it took a toll on my brain in a different way. My brain was very tired at the end of the day and couldn’t think beyond that work.

I had to learn how to process all the previous things in my life that were bad so I could move on and take on new things. Once I was able to do that, which involved a year of therapy, I was able to continue to do my job well and also come home, go for a run, cook dinner, and then settle down into side projects. I feel most comfortable in that routine.

Do you feel creatively satisfied? No, I don’t. I don’t think I ever will. I would do really bad work if I thought I was satisfied. There’s a piece of me that believes that if I’m not about to die, I won’t make something great. It’s about creating urgency.

When I came to Amazon, I owned two suitcases worth of things. I needed to buy a couch for my apartment, but I didn’t want to do it. I put it off for two months. I had sheets and a pillow on the floor. I resented building a home because I thought that if I started to build a home, then I’d settle down, and if I settled down I wouldn’t be able to make things because I wouldn’t have anymore life experiences. I’d have no more stories to tell.

And moreover, I was balancing that with this idea of being a trans punk person in tech. The people I make friends with work in cafes and bars and our relationships are strong right up until they find out I work in tech and then it starts fucking everything. It creates a disconnect within my own community.

Eventually, I bought a couch. Then I just filled my apartment with stuff. I was working hard and deeply ingrained with projects and my brain was filled with information, so I’d come home, sit on my couch, and watch movies to help me process. After a while I went to my therapist and told her I hated what my life had become. Plus, MyTransHealth had just launched and I was mad about it because I didn’t think it was good enough.

I felt guilty. I felt bad about being a person in my community doing this work knowing damn well what other people in my community are living in. My therapist told me it sounded like I had survivor’s guilt. She told me to go home and Google it. Survivor’s guilt coupled with PTSD basically equates to war films, so I started watching war films. This may be a stretch but follow me here. War films have two things: one, toxic masculinity, and the second is this idea of coming home and being unable to communicate what the hell has happened in your life and breaking off from your own community because of it. Turns out war films were weirdly the thing to help me process my life.

Then when the election happened, I forced myself to get back into the grind. Kade and I redesigned MyTransHealth to scale faster and have a stronger mobile experience. Now when I get home, I don’t sit on my couch. I’m here at my desk and I focus on the work. I’m speaking more. I’m writing more.

So, no. I’m not creatively satisfied and I hope I never am—but I’m doing everything in my power to ensure I always strive for it.

“I’m not creatively satisfied and I hope I never am—but I’m doing everything in my power to ensure I always strive for it.”

You mentioned the disconnect from your community because you work in tech. You’re active as an advocate on Twitter. Has using your platform to speak helped bridge the communities that you’re a part of? My internet communities, for sure. But when I go to my coffee shop, they don’t know my internet life and they have no idea what I do. I want to keep it that way as long as possible. I want to be real.

Having a platform on the internet is great. It’s something I curated for a while to do what I wanted it to do. The way I talk on Twitter is for my community. If you read that from an outsider’s perspective and you get it, that’s great. But I’m not going to sugarcoat it for you. The thing that’s so bizarre to me, from the bathroom nonsense to the way trans people are positioned to talk about their lives in media, is that everything is catered to people who aren’t trans.

In 2013, I read this book called Nevada by Imogen Binnie. It changed everything for me because it was a book about trans people written by a trans person, but it wasn’t a memoir. It was a fictional story and it was written for trans people. The language used wasn’t 101 level. That book helped me realize the things that I make can just be for trans people, and that’s it.

With our political and cultural climate right now, I’m interested in the idea of two people coming together to get curious about each other’s lives and ask questions with the intention of listening to understand. I know Twitter isn’t the venue to do that, but have you had any meaningful dialogue on Twitter? It comes down to trust. Can I trust you? Will you hurt me? Like, am I going to lose my income if I speak out against you? Twitter can be a horrible place to have that kind of conversation.

Actually, the reason we’re doing this interview is because Timothy Goodman put us in contact. I know Timothy because he was doing 12 Kinds of Kindness with Jessica Walsh and there was this one slightly awkward trans moment that happened where he did this gender role reversal, but played up some stereotypical femme stuff. I was mad because I don’t want the world to think I’m that.

I didn’t know Timothy at the time. I didn’t know if he would give a shit, but after thinking about it for two weeks, I sent him a tweet telling him I felt weird about it. He sent me a sweet note back and asked if we could get on the phone and talk about it. I said yes. We got on a call and talked over two hours about gender, the role of design, what we can do better, the stories we tell, and how we use positions of privilege to do good things. It ended up being a fantastic conversation that led to a great friendship. Can two people who are relatively open-minded have a conversation? For sure.

What do you wish people knew or understood about you that they don’t? Ooh, this is another story. A week after the election, I opened my door to leave my apartment and there was a couple fighting and screaming in the hall. I had seen them before and knew they were together. I had my hand on my doorknob and was waiting to make sure she was okay. After a minute I realized I was just eavesdropping on a break-up.

She screamed and cried about her hurt in a way that was so authentic and pure. I was so envious of her—not of her hurt, but that at some point in her life, she learned it was okay to be vulnerable enough with somebody to open herself up to being hurt. And she was pouring it out in the truest way I’d ever heard. I never learned that. There was no media narrative about the world loving somebody who looked like me or had my body. There was no message that said trans women can be loved and appreciated and not fetishized.

I never learned how to be that vulnerable in a relationship because I was only taught to survive. And sure, I survived, but it came with a cost. Even when I was trying to date that woman back in Maine, it was never truly authentic. I wanted her to help me not be trans. The idea of loving somebody authentically and wholly is something that was never shown to me, and it’s not being shown to trans girls who are growing up right now. What I want people to know is that we need to start telling some fucking love stories with trans women in them.

The past few years have been about, hey, do you know that trans people exist in the real world? But let’s get to the human shit, which is the fact that we’re able to love and to be loved authentically for our bodies. That’s the thing I want people to talk about. Pure love.

It’s the whole range of human experiences that are universal to all of us. It reminds me of this quote from Pema Chödrön’s book, When Things Fall Apart: “In the midst of loneliness, in the midst of fear, in the middle of feeling misunderstood and rejected is the heartbeat of all things…” We are united in those experiences, including love. Yes. People are people. This sounds fucking bizarre, but I don’t think a lot of people realize that trans people are actual human beings that breathe. When I walk my dog, people smile at me in a way they didn’t before I had him. When I don’t have my dog, I’m some trans girl walking down the street and you don’t know what my deal is, but you think I look weird. When I have my dog, I’m a human being taking care of another breathing thing. It humanizes me. It’s kind of fucked up that it takes a dog for strangers to see me as human.

I want to ask you one more thing. Considering where you are in your life right now, if you could go back and talk to your younger self, what would you tell her? I’d just tell her to carve out space for yourself as early as you can in order to transition and then just move the fuck on. The climax in the majority of stories about trans lives is the transition but that’s wrong. The book doesn’t even really start until after the transition.

Figure it out. Don’t compromise. Don’t wait. Move the fuck on. Let go.