- Interview by Tina Essmaker September 30, 2014

- Photo by Ryan Essmaker

Steven Heller

- curator

- designer

- editor

- educator

- writer

Steven Heller was an art director and senior art director at the New York Times, originally on the OpEd Page and then for the New York Times Book Review. He is currently co-chair of the MFA Designer as Author Department, author of over 170 books on design and popular culture, and writes the Visuals column for the New York Times Book Review, a weekly column for the Atlantic online, and The Daily Heller for Print magazine.

Tina: Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

I’m 64 now, and as I get older, it gets harder to remember the path. It gets harder to remember everything. But when I was a kid, I had a precocious streak, and I made publications and then tried to sell them. I don’t remember what the content was, although I don’t think it was very profound. When people asked me what I wanted to be, I’d say, “I want to go into advertising,” maybe because of a movie I saw or some character I’d liked on TV. But I also wanted to be a cartoonist. As things started to progress and I entered high school in the 1960s, I started showing my work around. It was cartooning, but with an introspective bent. I was hired by an underground paper called New York Free Press.

How old were you?

I was 17. They hired me to do paste-up and mechanicals, which I didn’t know anything about; they taught me on the job. They ran a couple of my cartoons each issue as payment. I was supposed to get $50 a week, but I don’t remember getting much of that. I wasn’t that good at paste-up and mechanicals, but I learned how to use type, and I had a few mentors there. Eventually, I stopped drawing cartoons because I wasn’t good at it.

Then a group of us started a magazine called Screw, which was the first sex tabloid in the city. I ended up having an argument with Al Goldstein, who was the cofounder and publisher of Screw, and I started my own magazine with the staff from the New York Free Press. We called it the New York Review of Sex and Politics, and it took off.

Five years after that, I was hired to do the OpEd page of the New York Times as art director. I was 23 or 24 when I started there, and I stayed at the paper for 33 years. That gave me the opportunity to write books and put on exhibitions and learn about political graphic commentary. Then I branched out from the history of caricature and cartoon into design, because a lot of the people who were players in one area were players in the other.

Did you have formal training or did you learn on your own?

Well, I went to New York University (NYU) for almost two years, where I was presumably an English major. It was the 1960s, so the school actually got closed down by antiwar demonstrators at some point. Plus I had my job while I was there. And I got thrown out for various reasons, one of which was because I was doing comics for Screw and somehow the school got ahold of a copy and saw that one of the comic strips had my philosophy professor in it—I used his name because it was a great name, which I’d rather not divulge.

Then I was out of school for a little bit, got reclassified in the draft as 1A, and enrolled at the School of Visual Arts (SVA), where I was accepted as a freshman. I never went to class because I was working. They wanted to know why I wasn’t going to classes, so I showed my portfolio to the chair, Marshall Arisman, and he said, “If you come back, I’ll make you a senior,” just so I could get my draft deferment. I never went back, so he threw me out. He’s now been one of my closest friends for forty years, and we’ve done four books together.

“New York tends to be a meritocracy…People judge you on who you are, what you are. If you’re a pain in the ass, but do great work, you still might be embraced—but you won’t be taken to dinner.”

You mentioned working at the Times for 33 years. How did that chapter end and the new one at SVA start?

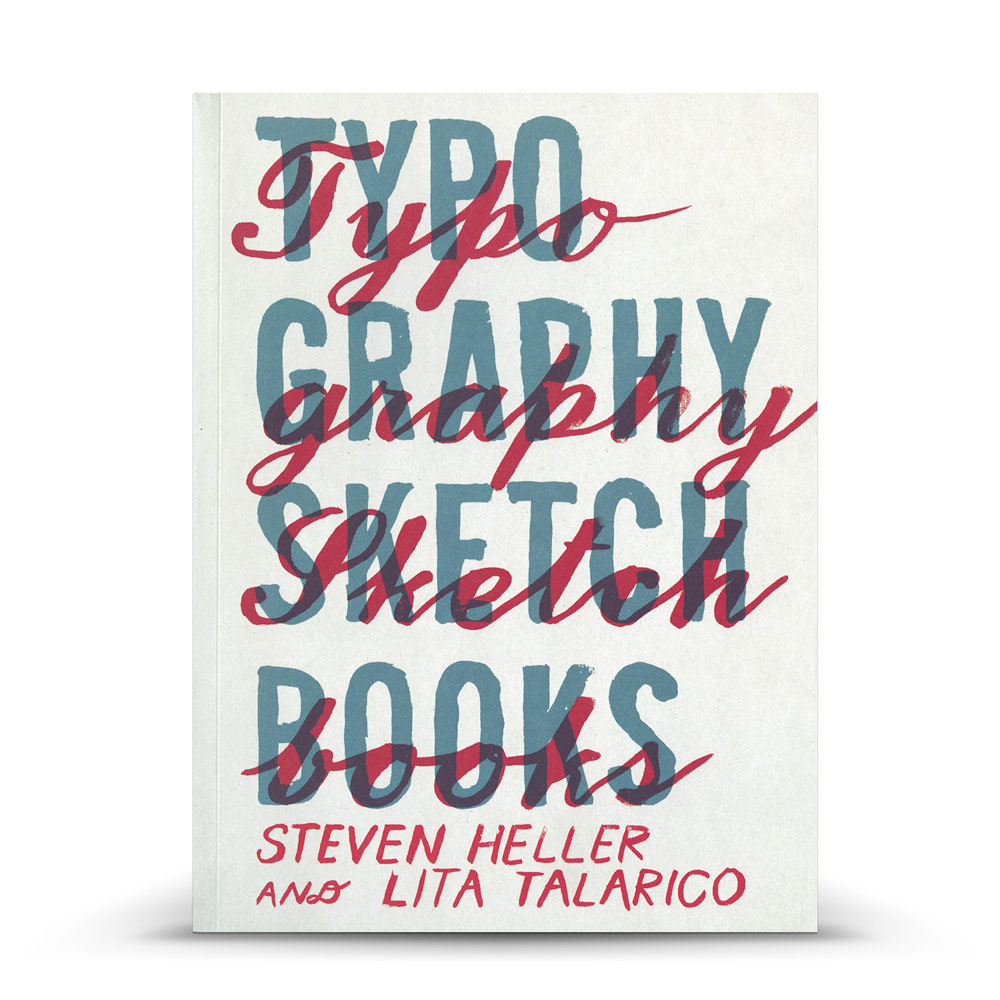

Well, the chapters overlap. I just got my 30th anniversary watch from SVA, so I was teaching here at SVA while I was at the Times. Then 18 years ago, I was asked to start a graduate program here. I brought in a colleague of mine, Lita Talarico, who I’d worked with on some book projects earlier on, and we cofounded the MFA Design/Designer as Author and Entrepreneur.

There’s always been an overlap. I did books while I was at the Times, wrote for magazines while I was there; the Times asked me to write for them. It’s one big mishmash. I couldn’t give you a timeline.

And what are you focusing on right now?

Right now, my job is to help develop graduate programs for SVA. I lecture in the MFA Design program, which I co-chair with Lita, as well as another program that I cofounded with Alice Twemlow on design criticism. I write three or four books a year, and I do articles and whatever else comes along.

You’ve done so much. Have all of these opportunities come about because people saw your work and approached you or were you out there trying to make these opportunities happen?

I was always out there trying to make opportunities happen, but not in an ultra-aggressive way. When I did something I thought others might be interested in, I’d mail it out to people. It was like networking without the Internet. And I’d meet people, too. For example, I had been contracted to do a book on contemporary caricature and cartoon, and I needed an intro for it. I knew that Tom Wolfe was interested in this area, so I wrote him. We got together, and he wrote an introduction for an exhibition that I did, which was more historical. Then I asked him to do the foreword for my book, and he did. A lot of opportunities came out of cold calling people, who I found to be accessible; now, with the Internet, people are extremely accessible.

I’ve found the same to be true, especially in New York.

New York tends to be a meritocracy, which is nice. People judge you on who you are, what you are. If you’re a pain in the ass, but do great work, you still might be embraced—but you won’t be taken to dinner. (laughing)

Before we started the interview, you mentioned that you grew up here. What was your childhood like? Was creativity encouraged?

Well, creativity wasn’t distinct from anything else. I grew up a couple blocks away from where we are now, in Stuyvesant Town, a middle income housing project that was made for veterans returning from the war. That was when the US had a middle class. I was brought up in a very liberal Jewish background. My mother worked in the childrenswear business, meaning she was a buyer for a company that owned big department stores and traveled all over the world. She had the air of a creative, but that wasn’t a job at the time, particularly for a woman. She was ahead of her time having a full-time job for most of her life. My father worked for the Air Force, and I wanted to do the same in the way kids follow their fathers. His office was only a few blocks away, so I’d hang out there. Every so often, he’d take me to an Air Force base, and it was very appealing because it was before the Vietnam War, when it seemed like there would never be another war.

There were always things to get involved in. As a kid, I could walk around quite freely. When I was 10, I worked for the Kennedy campaign in New York, uptown on 42nd Street. I was able to go by myself to this. It was always dangerous, but never so dangerous that you’d expect to get robbed or beat—those things did happen to me, but it seemed like the gestalt of New York. As I grew older, I was involved with different groups of people who had creative stuff going on. Ultimately, in the 1960s, it exploded.

You’ve experienced so many phases of New York. I couldn’t imagine growing up here and watching it change so much.

Yeah, but if you look at old photos and newsreels from before I was born, it also seems different, but it doesn’t necessarily feel great. When you’re living in the moment, you’re living in the moment; whatever that moment is, that’s your reality. Everything else is a myth. My reality is what I do now. I can look back and probably romanticize it a bit.

“…my current wife, Louise Fili, is one of the most accomplished graphic designers around, and we’ve done 15 or so books together…I used to say, ‘You don’t shit where you eat,’ but it’s much easier to have a life with somebody who you’re on the same track with.”

Did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew what you wanted to focus on?

Yeah, it was when I was at the Free Press the first year, and I didn’t want to go back to college. A lot of people have those kind of moments, but they usually get talked out of them by their parents, or they get ordered out of them. I had an uncle who was a professor at Columbia, who’s still alive at 93. He was a radical when he was younger, and he interceded on my behalf with my parents, who came out of an immigrant family and wanted me to go to college. My parents were liberal enough and adjusted to meet my needs after my uncle told them, “He can take off! He doesn’t have to go to college or he can come back to it.”

You briefly mentioned mentors earlier. Did you have any mentors or influential individuals in your life?

When I was at that pivotal stage, I met an illustrator named Brad Holland, who is still a pretty well-known illustrator. He was a rebel in terms of the culture and context of what was going on at the time—it’s too long to get into. He was a formative influence on me, and he was the reason I stopped drawing. He was so good, and I was not; he never gave me any props for it, so I stopped. One day, after I hadn’t seen him for a few weeks, he said, “I haven’t seen your drawings lately,” and I said, “I’ve stopped doing them,” to which he replied, “Well, that’s too bad. They were good.” I never went back to it other than at the Times when I ran out of a budget and did my own illustrations under a pseudonym. Brad taught me what typography was; he taught me how to think; he got me off the rail.

Are your family and friends supportive of what you do?

Oh, yeah. My parents both died last year. When we went to clean up their place, they had clippings and all sorts of stuff that I’d done.

My first wife was a social worker, and my second wife was an Irish Revolutionary. But my current wife, Louise Fili, is one of the most accomplished graphic designers around, and we’ve done 15 or so books together. It’s kind of like your situation with your husband. You know, I used to say, “You don’t shit where you eat,” but it’s much easier to have a life with somebody who you’re on the same track with.

People ask Ryan and I about being life and business partners. It works for us, and we like that our lives aren’t segmented.

I like it for a number of reasons, but one is that she’s such a damn good designer. When we work together, I do my part, and then it goes over to her and she interprets it; those interpretations are like having a baby every six months or something. What will it look like?

I feel like with Ryan, too. He’s so good at what he does. If I send him copy, I know he’ll make it look amazing. So, has there been a point when you’ve decided to take a big risk?

I don’t know. I think most things are risky. Waking up in the morning and going outside is a risk. To be honest, I don’t like change all that much, but I’m happy to change if I’m given the opportunity to ponder what I’m doing.

I’ve jumped into things, but I don’t think of them as risks. Behaviorally, it’s just what I have to do. When I think of something as a big risk, then I won’t do it; if I think of it as part of a continuum, then I’ll do it. Or I do things without thinking or knowing there will be a consequence, but not caring what it will be. It took me a long time to decide to leave the Times.

I was going to ask if that was a risk.

It was a very difficult time. As you can see, I shake; I have Parkinson’s. I believe I got it because of the tension and stress over leaving the Times, because that’s when it came on. It could have been there anyway, but I think it exacerbated it. I’m on contract at the Times, and am going there next week. But that was a major disruption in my life. While I was there, I could do all these other things that some might call risky or obsessive, but I had a structure. Losing that structure, even though I had a beautiful parachute into this structure, wasn’t easy. It never is. But others have worse problems, so I consider myself lucky.

Do you feel a responsibility to contribute to something bigger?

I feel like there’s a requisite to do that, which occasionally freaks me out. Again, if it’s a natural occurrence, I do it and don’t think about it. This is a metaphor or explanation for that. When I walk down the street and see someone who is blind, tapping their way to the corner, I go through agony deciding whether or not I am going to help them cross the street. I can’t tell you why. At first, I was self-conscious; then there was the idea of rejection or doing it the wrong way.

Do you view what you do at SVA as a way to give back?

It is. The students come from all over and my job is to help them excel. There are a lot of students who end up working with me on projects. I feel like I’m having an influence on a very micro level, on a very select group of lives.

“There are all sorts of platitudes I used to give, but they’ve become so rote that I don’t say them anymore. I used to say follow your passion. How many times have you heard that before? But it’s true. If you follow what you’re most interested in, hopefully you’ll get to the place where that becomes your career.”

Are you creatively satisfied?

No, I’m never satisfied. My son is a filmmaker, and I love that he is; I live vicariously through his burgeoning career. I wish I could’ve made films. When I left the Times, all of my technical strengths stayed there. I now rely on a lot of people to do things I used to be able to do myself. Creatively, there are so many people who do wonderful things, and I’m good at finding them and putting them together.

Is there anything you’d like to do in the next few years?

I don’t know. I keep saying I’d like to make a film, but the stars have to be in alignment. My son and I were talking about doing a film together.

I’m working on five or six books right now, but there’s not the challenge book. The books I’ve wanted to do because they represented the things I was fascinated with, I’ve already done. I’m interested in the ones I’m working on, but it’s not that same bubbling passion.

What advice would you give to someone starting out?

There are all sorts of platitudes I used to give, but they’ve become so rote that I don’t say them anymore. I used to say follow your passion. How many times have you heard that before? But it’s true. If you follow what you’re most interested in, hopefully you’ll get to the place where that becomes your career. It’s just one of those things I don’t like saying and people don’t like hearing, because it’s not a how-to.

I wanted to be an illustrator, but I couldn’t, so I found something else within the same area. When I was at the Times, I saw hundreds of people every month, and I’d tell some of them, “This isn’t for you. Find something else.” Our jobs are to be encouraging and you have to figure out how to do that for each person.

I think we’re all good at something.

I’m not an atheist or agnostic or religionist, but I have this cosmic view: I do believe that there’s a higher structure and somehow we’re all imbued with something—it’s just a matter of finding it.

I agree. How does living in New York impact your creativity?

New York is everything. I have a house in the country, and I can only stay there two days at most. It’s beautiful, and I love it, but I have to come back here. I was born and raised here, and I don’t plan on leaving. It has everything I want. At the same time, I don’t take advantage of 99% of what New York has to offer.

Is it important to be part of a creative community of people?

All my friends are in this business more or less. Being involved with creative people is great when you want to work on projects together or when you want to talk about something. There’s a certain competitive quality, too; you want to show that you’re on the same level. Everybody finds a group to be part of, hopefully.

What does a typical day look like for you

Wake up, go to the gym, shower, work, lunch, work, kibitz, work, snack, kibitz, work, dinner, BBC murder mysteries, sleep, and dream about work or murder mysteries.

What kind of legacy do you hope to leave?

The funny thing is that I already have a legacy because I’ve done over 170 books. Presumably, because a lot of it is online, it will be available and will hopefully have some meaning to other people. I want to feel like I’ve made some sort of contribution to the field I’m in, as minor as it is. I’ve often visualized my own funeral, but I also don’t like thinking about it. As you creep up in years, even though there are theoretically a lot left, anything can happen.

“I’m not an atheist or agnostic or religionist, but I have this cosmic view: I do believe that there’s a higher structure and somehow we’re all imbued with something—it’s just a matter of finding it.”