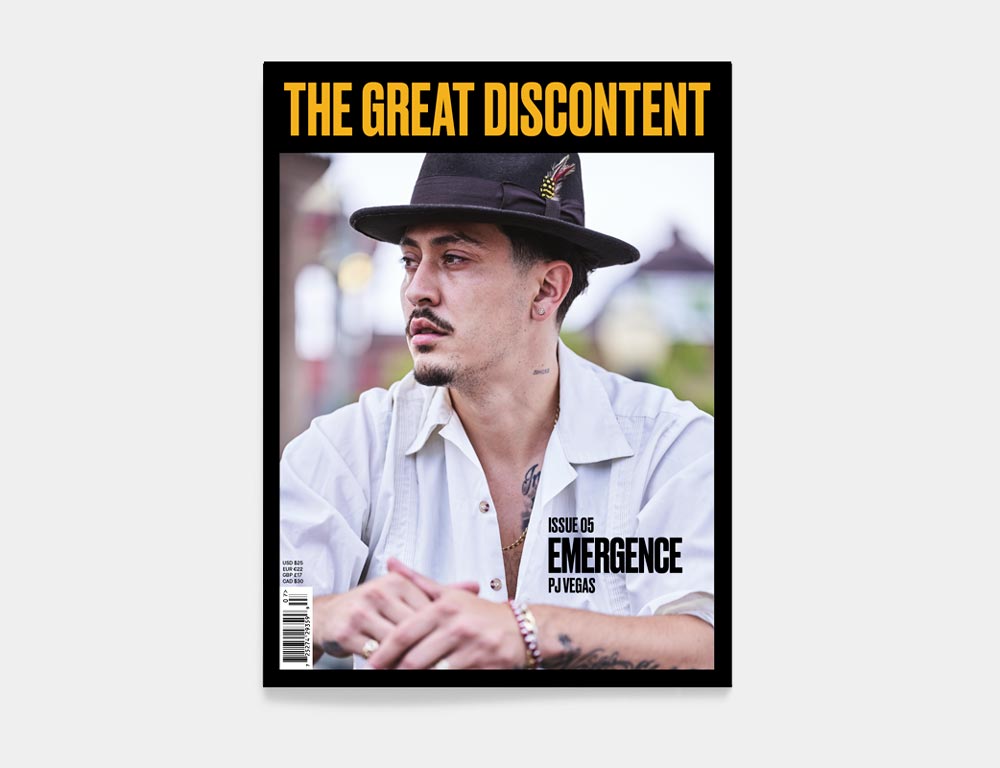

Emergence Issue: TGD's fifth issue features a dynamic group of 15 creators who are deeply committed to addressing systematic challenges in their communities through creativity and emerging ideologies. Buy Now

According to your website, “Carly Ayres is a writer using language and interaction to engage people in new and interesting ways.” It feels like there’s this whole body of work in one simple sentence. Can you talk about where you’re from and how it shaped your understanding of your work?

I grew up in Bradenton, Florida. It’s on the Gulf Coast. Our town was well known as the home of Snooty the Manatee, the longest-living manatee in captivity. I don’t know if it’s that I haven’t been back in over two years, but I have a little bit more nostalgia for Florida. Where I grew up, it was very beachy with lovely kitsch to it that I’ve found ways to incorporate into my life that I’m probably not aware of. It’s easy to imagine high school Carly hanging out with Snooty the Manatee when this dream emerges.

What is the catalyst for a New York dream while growing up beachside in Bradenton?

It’s probably not too dissimilar from a lot of other creative individuals’ origin stories in that there’s a public school art teacher involved. I’d escape over to the art room and find a bit of refuge there. I was privileged enough to have access to after-school art classes and programs. My parents were pretty invested in developing my interests. My mom would take me to art classes at Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota on the weekends and after school. My mother’s father had actually gone to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). That was the only art school I applied to. As a young, emerging capitalist, I was like, “I like this art thing, but I’m not going to pursue it because it’s silly and I’m sure there’s no money in it.” It was really more of a lark. I applied and ended up getting in.

What was the alternate path?

Engineering, easily. I was also good at math and was under the impression that mechanical engineering was like Legos for adults. [Laughs] But once I visited RISD, I discovered industrial design, which really felt like a melding of art and engineering. Before that, I didn’t even know the field existed.

What did that season of discovery look like for you?

I was like, “Oh, these are all the other weird kids in their high schools.” It was the feeling of acceptance but also deep insecurity. I think there’s also a moment of comparison where, all of a sudden, everyone is very good at this. A big RISD thing is that you draw a bike as part of your application. To do mine, my sister got in the pool with a bicycle and I drew it being underwater. I remember thinking it was pretty good. They do a gallery show of everyone’s bikes once you get there. One of the most imprinted moments was walking in for the first time to see all these bikes. I remember thinking: “I made a terrible, terrible mistake. I am so out of my league. What have I done?”

Were your parents creative people? It sounds like they were very supportive.

I think both my parents had decided for themselves that they wouldn’t pursue creative careers for the same reasons that I was also kind of anti–having a creative career. My mother’s dad who had gone to RISD became a boat captain, ferrying wealthy people’s yachts around to them at different ports. He really discouraged her from going into art. He was like: “Don’t do it. There’s no money. You’re going to have to become a boat captain.” And my dad was also pragmatically minded when it came to careers. He became a doctor, although he wanted to be an architect. He was always pursuing various projects—he was maniacally into mobiles for, like, months. My mom was very crafty. She did murals in our bedrooms that would change as we got older. So, there were elements of creativity around me, but I don’t think I ever saw how that would translate to creating full time.

There’s something about navigating that friction of choosing a regimented path but having a compulsion for creation.

I remember my father got really into building foam core models for a while. He’d choose the messiest projects, and they’d be all over the house. [Laughs] As a kid, I remember thinking it was incredible. I’m sure that influenced something. There’s definitely a bit of wonder to it, but yeah, friction is a good way of putting it.

“It all makes total sense, in retrospect, but that was not what I was supposed to be doing at the time. I remember it kind of felt shameful. I was always getting in trouble for not doing the actual assignment.”

Do you remember when you realized that you could make a career in this space or that you were on a path that had a profession tied to it?

I was much more digitally minded than a lot of my peers. It’s usually a physical craft based school. We were woodworking and metalsmithing. When I started, the industrial design program at RISD had no online presence. So I took it upon myself to build one for them and made a blog. I’d interview people, and I built an editorial team. It all makes total sense, in retrospect, but that was not what I was supposed to be doing at the time. I remember it kind of felt shameful. I was always getting in trouble for not doing the actual assignment. I was like, “Well, I made a website that we can now use to get jobs.”

I’d make press releases for my classmates’ work. [Laughs] Looking back, it makes total sense that I would be helping my classmates articulate what they’re doing. That translates so clearly to the work that I do today. I work at Google, and I feel like a big part of my job is explaining the value of the things that I am doing and the value of the things that the designers are doing.

What’s the through line of the work you’ve done so far?

It gets more clear every year. When I was graduating, I called myself a specialized generalist. I had a job interview with a notable start-up founder who looked at my portfolio and told me: “You will never get a job. This is absolutely illegible. I’ve no idea what I would hire you to do.”

That moment helped me realize that words are a tool that help people understand what you do. And it’s really important to come up with the words that people understand. You need that box. And because my box is not singular, I’ve always needed to come up with that language. I’m a designer with a bit of a writing streak. I connect a lot of disconnected dots and pull the words together that describe how all these things connect to each other. The output shifts, but usually it’s about bringing different insights, interviews, conversations together to inform an experience. That might be a website, a brand book, a set of guidelines. Sometimes it’s a deck, sometimes it’s a doc. Usually, I’m collaborating with designers, too, adding visual flavor to whatever that experience ends up being. At Google, that makes me a UX content strategist.

You’re also a collector. You have a sense of the vitality of objects and images. What role does collecting play for you?

Our friends call our home Tchotchke Village. I especially like things that bring joy and are delightful and fun. Over the last couple of years, I’ve really gotten into vintage toys and puzzles and have accumulated quite a collection of those. I love learning new things, and I guess there’s probably a curiosity connection between the two.

How do you know that some unnecessary object has to come home with you?

I’ve always been a “more is more” kind of person, right? Everything in excess. A lot of colors. Maybe it actually ties back to my kitschy upbringing in Florida. I really had to learn to limit what comes home with me. I’ve had to exert some restraint. I started an Instagram account to share what I find because I can’t own it all. Sometimes just appreciating it and figuring out its origin is nice.

Where does that show up in your work?

With the rise of tech, I think there’s been this real push—even with design systems—toward homogeneity. All websites look the same, all apps, all illustration styles. I think it’s been a push toward systemization and efficiency. You’ve got to define the rules before you can break them, but it’s really made me yearn for something that doesn’t need to exist. Give me something where it’s about play or joy or these things that I feel have been designed out of everyday experience in favor of utility or usefulness. The way to get messages to stick and to get people to care about things is to get them to play around.

How can you use interaction as a tool to create something that’s a little bit more fun, a little bit more joyful and playful?

I’d love to get back into physical design and start making some unnecessary objects again. Everyone should be able to live in a space where they’re surrounded by things that make them happy. This space is definitely becoming that for me. I love to collect things made by my friends.

It sounds like you have to surround yourself with playful collections and diverse inputs to be able to have the fodder and ingredients to create something transformative.

I think that’s true with my work with people—and building community, too. If you can have a diversity of people, objects, ideas in a space, you get a lot of unexpected takeaways that are harder to create otherwise.

Who are the people who are exploring edges in a way that’s inspiring you or informing your work?

It’s an infinite list. People who use technology as a tool in interesting ways. I love Laurel Schwulst’s work and other folks trying to bring poetry into technology. The School for Poetic Computation and Maya Man, an artist, programmer, and dancer, are both doing some really wonderful work in that space. Anne Helen Petersen’s writing on culture and burnout and anthropologist Shannon Mattern’s on infrastructure and maintenance. In the tchotchke realm: Italian modernists Enzo Mari and Bruno Munari. My list of inputs is long. It’s an extensive bibliography of people who excite me.

What’s next for you as a creative person?

Coming to Google was not necessarily part of the game plan. When the studio shut down, it was unexpected for me, and I didn’t really know what I was going to do next. So when people I’d been working with at Google reached out to me, it posed a kind of a resting place for a bit. Of course, there’s very little rest. [Laughs] But it was a little bit of stability. It’s a growth-minded time when it’s really not about the ego. It’s not about my personal practice as much, although I think it’s really informed my personal practice outside of work.

I recently retired from 100sUnder100, or “Hundos,” the community I’d been organizing for six years or so, and I think what’s next is figuring out what is going to fill those spaces. What’s the next community-related project? Is it a studio? What’s the next need to be solved?

“Our job, our identities as creatives—all this stuff is tied to how we make money. Losing how you make money is terrifying.”

The first time we met was as HAWRAF, your studio, was closing down, and I remember being incredibly inspired by the courage of deciding something can end. I think we’re so culturally resistant to endings.

It was easier knowing that I had been through it before. Our job, our identities as creatives—all this stuff is tied to how we make money. Losing how you make money is terrifying. I was fortunate that we had done really well financially with the studio, so there was a time line of like, okay, you get to figure things out for a bit before you need to figure it out because you need money to live. That is a very real constraint of my practice, and acknowledging that is important. Having done it before in ways that were way less graceful and having made it out on the other side gave me confidence. I remember I quit Creative Mornings to join this small studio, and it didn’t work out. I was like: “Oh my God, this was it. This was the plan.” I did not at that time have money saved to figure things out. I started freelancing immediately and took on way too much work. As a studio, HAWRAF was respected; it was a good portfolio to jump to whatever was next. But everything is relationships for me, too, so having the money was important, but also that stronger network was the safety net to then figure out what I wanted to do next. With each job, each opportunity, each project, you’re a little bit more established. You have a little bit stronger of a network, you have more to fall back on.

So, is the legacy the relationships?

The thing that I get most excited about and that helps me decide what to focus on next is seeing the connections. Not just my relationships, but the relationships that were then enabled by bringing people together, by creating the spaces for people to meet each other, for ideas to be exchanged.

One of the most eye-opening experiences was the year-end review survey I sent out for “Hundos.” Part of it was wanting to understand more about the demographics of that community and figure out how to improve it to have a more diverse membership. But another part was asking: Who have you met? What’s happened? What’s really exciting is the compounding relationships. You become part of a system. It’s about asking, “How can you be a good part of that system and make the system better and improve it through enabling connections with others?” The legacy is a big party where everyone knows each other and has access to more things which, leads to a lot more exciting projects.